Joseph Martin (general) facts for kids

Joseph Martin, Jr. (1740–1808) was an important leader during the American Revolutionary War. He was a brigadier general in the Virginia militia. Martin was known for his smart talks with the Cherokee people. This helped stop Native American attacks on settlers, especially those who fought in the key battles of Kings Mountain and Cowpens. His actions also helped keep the Native Americans neutral, meaning they didn't side with the British during these important battles. Historians believe that the American victories at Kings Mountain and Cowpens were turning points that helped the Americans win the Revolutionary War.

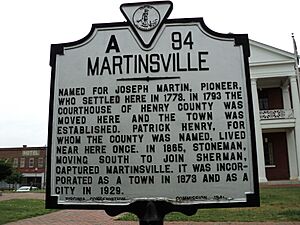

Martin was born in Caroline County, Virginia. He later lived in Albemarle County and then in Henry County, Virginia. His home, called Belmont, was on Leatherwood Creek in Martinsville. This was not far from his friend, Governor Patrick Henry's plantation, Leatherwood Plantation.

General Martin had many different jobs throughout his life. He was a farmer, an explorer, and a pioneer. He helped build Martin's Station in the "wild west" of that time. He also surveyed (measured) borders between states like Kentucky, North Carolina, Tennessee, and Virginia. He worked as an agent for Native American affairs for Patrick Henry and helped with peace treaties. Joseph Martin, along with Dr. Thomas Walker, even named the Cumberland region and the Cumberland River. He served in the government of Virginia, Georgia, and North Carolina. He was friends with famous people like General Thomas Sumter and Colonel Benjamin Cleveland. The city of Martinsville, Virginia, was named after him while he was still alive.

Contents

Early Life and Frontier Adventures

Joseph Martin Jr. was born into a well-known Virginia family. His father, Joseph Martin Sr., came from a wealthy British family. However, his father's family in England didn't approve of him marrying a colonist from Virginia. Because of this, Joseph Martin Sr. was cut off from his family's wealth in England.

Joseph Martin Jr. didn't want to live the quiet life of a Virginia planter. When he was young, he ran away and joined the army during the French and Indian War in 1756. He served at Fort Pitt with another young Virginian, Thomas Sumter. After his army service, Martin went to live on the frontier. He dressed in buckskin clothes and became a fur trader, trapper, and fighter. He also bought and sold land.

One of Martin's first big trips was for his family friend, Dr. Thomas Walker. Martin's son, William Martin, later wrote about how the Cumberland region got its name. He said that his father and Dr. Walker were with Cherokee chiefs. They found a spring and drank to the health of the Duke of Cumberland. This is how Cumberland Mountain and Cumberland River got their names.

In 1769, Martin tried to start a settlement in Powell's Valley. This was 100 miles (160 km) further west than any other settlement at the time. Martin and his group hoped to claim a large area of land. Martin's Creek in that area is still named after him. Even though this first settlement didn't last, Martin proved himself as a tough explorer. Even famous explorer Daniel Boone was surprised to find Martin's group already there in 1769.

By 1775, a merchant named Richard Henderson bought a huge amount of land from the Cherokees to start the Transylvania colony in what is now Kentucky. Henderson chose Martin to be his agent in Powell's Valley. This was one of many times Martin would work as an agent, using his experience living among the Cherokee in the Appalachian wilderness.

Martin's Station: A Frontier Stop

Martin's Station was a fort along the Wilderness Trail near Rose Hill, Virginia. The first fort was built in 1769, but Native Americans attacked Martin's group. He returned in 1775 and built a new "Martin's Station," but was attacked again and had to leave.

In 1783, he built his third "Martin's Station" closer to the Cumberland Gap. This small fort offered safety and supplies for hunters and families moving west into Kentucky. He finally sold his fort and lands in Powell County, Kentucky in 1788. He then moved back to Henry County, Virginia, to the town that would soon be named Martinsville in his honor.

A "fourth" Martin's Station was built recently at the Wilderness Road State Park. Builders used only tools from the 1700s to make it look real. They even used oxen and horses to move logs. Sometimes, reenactors would pretend to have Indian attacks to make the construction more authentic.

Life on the Frontier and Public Service

Joseph Martin was a strong and important person on the early frontier. He was over six feet tall and had 18 children. He was known for wearing buckled knee breeches and a long beard.

Martin married Sarah Lucas first, and they had seven children. After she died, he married Susannah Graves, and they had 11 children. At the same time, Martin also had a family with Elizabeth Ward, who was half-Cherokee. She was the daughter of Nancy Ward, a powerful woman among the Cherokee tribes. Having a family with a Cherokee woman was common for frontiersmen living among the tribes. Martin's son by his Cherokee wife was educated in Virginia but chose to return to live with the Cherokee people.

In 1777, Governor Patrick Henry made Martin the Agent and Superintendent for Native American Affairs for Virginia. Martin's job was to live among the Cherokee and keep peace between them and the settlers. He also held this job for North Carolina from 1783 to 1789.

During the American Revolutionary War, Martin's efforts helped stop the Overhill Cherokee from attacking American colonists. British agents had tried to get the Cherokee to join them. Martin's diplomacy in 1780–81 helped the Continental Army win the Battle of Kings Mountain. This victory helped end the war faster. General Nathanael Greene asked Martin to help keep the Native Americans neutral during the final battles of the war.

Martin also played a role in settling Tennessee by helping to move some Cherokee groups from the land.

By the end of the Revolution, Martin was a very important Native American agent. Virginia governor Thomas Jefferson asked Martin to get land from the Cherokees for a new fort. Jefferson also asked Martin to use his connections to get more land for the Americans between the Carolinas and the Mississippi River.

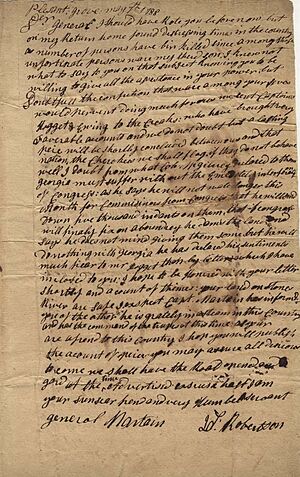

Later, Martin was accused of being disloyal because a letter he wrote to a Creek Indian leader was found. However, it turned out he was actually working as a spy for Patrick Henry to find out if the Spanish were involved with the Native Americans. Henry praised Martin's actions, saying he gave important information about the Creek Indians and their ties to the Spanish.

End of His Time as Indian Agent

Eventually, General Martin lost his job as chief Native American agent. Some people thought he was too easy on the Native Americans. This happened especially after an incident in 1786 when some young Cherokee warriors were said to have killed two settlers. Martin tried to calm the settlers and stop the Cherokees from joining other tribes.

However, Martin had also used military force against the Cherokees when they attacked colonists during the Revolution. In 1781, after a battle, Martin and other leaders warned the Indian chiefs that they had started the war by listening to the British. They said more fighting would lead to attacks on their villages. In 1788, Martin fought the Overmountain Cherokee and the Chickamauga Cherokee at Lookout Mountain.

But after working hard to make peace with the tribes, Martin was upset by the actions of the State of Franklin settlers. These settlers were often violent towards Native Americans. Patrick Henry agreed with Martin, saying that the Franklin people's behavior was "disorderly."

Martin's efforts to control the settlers of the State of Franklin made some people dislike him. They thought he was too "soft" on the tribes. Martin also became controversial after the Treaty of Hopewell in 1785. In this treaty, Martin and other government agents made agreements with the Cherokees and Choctaws. The Cherokee treaty especially made both the Native Americans and the colonial governments angry. The Native Americans saw it as a way to take their land, and the state governments thought it interfered with their power.

Because of these issues, Martin's job as agent was not renewed. Even though Patrick Henry tried many times to get him reinstated, the forces against Martin were too strong. In 1789, his career as an Indian agent ended. General Martin sold his large land holdings and returned to his lands in Henry County, next to Patrick Henry's property. He spent the rest of his life there.

Later, in 1790, Patrick Henry suggested General Martin for the job of governor of the Southwest Territory, but someone else was chosen.

Historians have different opinions about Martin's time as an Indian agent. Theodore Roosevelt wrote in 1894 that Martin was "a firm friend of the red race, [who] had earnestly striven to secure justice for them."

Serving in Government

Martin also served in the government of several states. He was a member of the North Carolina Convention that approved the United States Constitution. He also served many times in the North Carolina General Assembly. Later, he was elected to the Virginia House of Delegates. He finally retired because he was getting older. In 1787, the North Carolina assembly made him a Brigadier General. In the Virginia legislature, Martin supported James Madison's Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions. He was also elected to the Georgia legislature in 1783.

Martin was first part of the Watauga Association, which supported the founding of the State of Franklin. However, he left this group when he realized it might affect his role as an Indian agent.

Family and Legacy

General Joseph Martin, Jr. had seven children with his first wife, Sarah Lucas. One of their sons was Colonel William L. Martin, who became a Revolutionary War officer and later moved to Tennessee.

After Sarah's death, Joseph Martin, Jr. married Susannah Graves. They had 11 children. Five of General Martin's sons served in the War of 1812. One son, Patrick Henry Martin, was named after Governor Patrick Henry. Another son, Captain Lewis Graves Martin, also a War of 1812 veteran, moved to Tennessee. Judge John C. Martin, another son, became a judge in Tennessee and helped build the Cannon County courthouse.

General Martin also had two children with his half-Cherokee wife, Elizabeth Ward. One of their children may have been Nancy Martin Hildebrand.

The town of Martinsville, Virginia, was named in honor of Joseph Martin. For many years, he was not widely known. However, a historian named Lyman Draper began collecting stories about him, including those from Major John Redd, who served under Martin.

Many famous people are descendants of General Joseph Martin. These include his sons, Colonel William Martin and Colonel Joseph Martin, who were also important figures in government. Other descendants include Dr. Jesse Martin Shackelford, who founded a hospital in Martinsville, and United States Senator Thomas S. Martin. Several Alabama Governors, like Joshua L. Martin and Charles Henderson, are also his descendants. Alfred M. Scales, a Confederate General and later Governor of North Carolina, was also a descendant.

Toby's Freedom

Joseph Martin had a servant named Toby who was enslaved. Toby was a brave and strong man who helped Martin in several battles. Martin wanted Toby to be free after he died. When General Martin passed away without a will, his family decided together to free Toby. Toby became a free man and built a good life for himself. Martin's son, William Martin, called Toby "my fine old brother Toby."

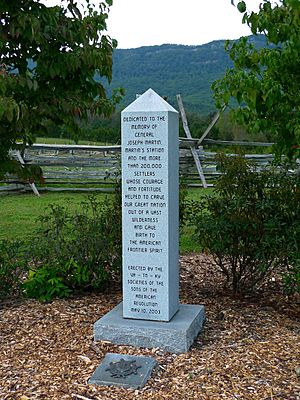

Recent Monument

On June 27–29, 2008, about 200 of General Joseph Martin's descendants gathered in Martinsville, the city named after him. They unveiled a monument in his honor during a special celebration.

See Also