Juan Vázquez de Mella facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Juan Vázquez de Mella

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born |

Juan Vázquez de Mella y Fanjul

8 June 1862 |

| Died | 26 February 1928 (age 66) |

| Nationality | Spanish |

| Era | 19th/20th century philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy

|

| School | Carlism Mellismo Traditionalism |

|

Influenced

|

|

| Signature | |

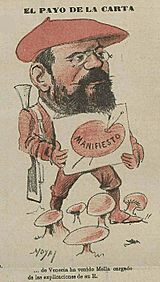

Juan Vázquez de Mella y Fanjul (1861–1928) was an important Spanish politician and a deep thinker. He is known as one of the greatest Traditionalist thinkers in Spain's history. He was active in a political movement called Carlism. He served for a long time as a member of the Spanish parliament, called the Cortes. He also became one of the leaders of his party.

Vázquez de Mella developed his own political ideas, which were called Mellismo. These ideas were so strong that they eventually led to a split in his party.

Contents

Early Life and Family

Juan Antonio María Casto Francisco de Sales Vázquez de Mella y Fanjul came from an old family in Galicia, Spain. His father, Juan Antonio Vázquez de Mella y Várela, was a military officer. He was known for his strong Liberal beliefs. He even faced problems for supporting certain political changes.

Juan's father resigned from the army in 1860. He was active in local politics. Juan's mother, Teresa Fanjul Blanco, came from a well-known local family. Juan was their only child. After his father died, Juan lived with his mother and later with cousins in Galicia. He felt more connected to Galicia than to his birthplace in Asturias.

Some people said Juan was born into a rich family. However, he later said that his family's wealth did not last. He spent much of his life with little money and died in poverty.

In 1874, young Juan started studying at Seminario del Valdediós. He was not the best student, but he loved reading books and newspapers. He preferred reading to playing with his classmates.

After finishing school in 1877, he went to Universidad de Santiago. He wanted to study philosophy and literature. But since that wasn't an option, he chose law. He didn't enjoy law and spent more time in libraries than in classes. He never married or had children.

Becoming a Journalist

Juan's father, a strong Liberal, died when Juan was a teenager. Even though some of his uncles were Carlists, Juan didn't inherit his Traditionalist views from his family. Experts believe he developed these ideas during his time at university.

He worked as a secretary for a professor who knew Marcelino Menéndez y Pelayo, a famous Spanish scholar. This gave de Mella access to important ideas. He left the university as a Traditionalist. Unlike many Carlists, he became one through careful thinking, not just family tradition. In the early 1880s, he started giving speeches in Santiago.

Around the mid-1880s, de Mella began writing for conservative newspapers. These included La Restauración in Madrid and El Pensamiento Galaico in Santiago. His articles in El Pensamiento Galaico became well-known, even in Madrid. He wrote strongly against a group called the Integrists.

The Carlist leader, Carlos VII, decided to start a new official Carlist newspaper. This newspaper, El Correo Español, began in 1888. It needed good writers. Some say the Carlist political leader, Marqués de Cerralbo, invited de Mella to write. Others say it was the newspaper's manager, Luis Llauder.

De Mella started as a correspondent for Correo. He also became the manager of El Pensamiento Galaico until 1890. He wrote many articles about political ideas and society. Soon, he was invited to move to Madrid and join the editorial team of Correo. Around 1890 or 1891, de Mella became the editor-in-chief. He was supposed to follow the guidance of Cerralbo, who was very impressed by de Mella's ideas.

Rising in Politics

De Mella's new role as editor-in-chief caused some debate. He was known for not always being in the office. He would work short hours and sometimes be away for days. The Carlist leader's secretary often complained about this. However, de Mella continued to write important and high-quality articles.

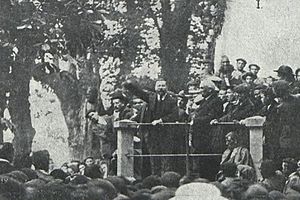

De Mella's success was also due to his work with Cerralbo. In the early 1890s, Cerralbo traveled around Spain to gather support. De Mella often went with him, writing about their journeys and speeches. Sometimes, de Mella spoke himself. His speaking skills gained him more and more attention.

In the 1891 elections, de Mella ran for a seat in the Cortes but lost. He tried again in Navarre, in the area of Estella. This time, he won after a tough campaign. This began a long period of Carlist victories in Estella.

As a member of a small Carlist group in the Cortes, de Mella didn't have much power over laws. But he quickly became famous for his speeches. He would challenge important politicians, and his speeches had a powerful effect on listeners. He was so respected that in the mid-1890s, he was offered a position as Minister of Education, but he turned it down.

He was re-elected from Estella in 1896 and 1898. He was now a Carlist and a parliamentary star. His public speeches were met with great excitement. The Carlist king, Carlos VII, was very pleased. In 1897, de Mella visited him and helped write an important document called Acta de Loredan.

In 1898, Carlos VII asked de Mella to resign from parliament. The Carlists were planning a coup to overthrow the government. De Mella helped by writing articles and giving speeches that hinted at the uprising. After another visit to Carlos VII in 1899, de Mella joined a Carlist group preparing for war.

Carlos VII later had doubts about the coup. But de Mella seemed to support those who wanted to rise up anyway. However, there is no proof he directly started the small revolts in October 1900, known as La Octubrada. After these events, the police searched de Mella's house. Carlos VII was angry and ordered de Mella to leave Correo Español.

Challenges and Return to Influence

De Mella obeyed his king's order. He left Spain for Portugal in late 1900 and lived in Lisbon for about three years. During this time, he sometimes visited Spain and wrote for various newspapers. He was not on good terms with Carlos VII. In 1901, he was even suspected of plotting to make Carlos VII's son, Don Jaime, king instead.

In 1903, he received a royal pardon. This allowed him to run for the Cortes again. After a Carlist member died, de Mella took his seat in 1904. In the 1905 election, he won in Pamplona. He would represent Pamplona for the next 13 years.

De Mella's position within the Carlist party was still uncertain. He was a nationally recognized figure. In 1906, he was even invited to join the Royal Spanish Academy. The party couldn't ignore him, but Carlos VII remained suspicious. The new party leader, Matías Barrio y Mier, wanted complete loyalty. De Mella strongly disliked Barrio and disagreed with his political strategy. De Mella wanted to form broad alliances with other extreme-Right groups.

After Barrio died in 1909, de Mella wanted Cerralbo to become leader again. He was angry when Bartolomé Feliú was chosen instead. Some people even thought de Mella himself might become the leader.

When Carlos VII died in 1909, his son Don Jaime became the new Carlist king. Don Jaime was pressured to remove Feliú. He chose a compromise: he kept Feliú as leader but made de Mella his personal secretary. De Mella was asked to prepare a new important document. However, their relationship was difficult, and they both became suspicious of each other.

After a trip to Rome in May 1910, de Mella was replaced. For the next two years, de Mella and his supporters, known as Mellistas, worked against the party leader. They openly supported non-dynastic alliances with other conservative groups. In 1912, de Mella openly attacked Feliú, calling him incompetent. He demanded Feliú's removal. Don Jaime eventually gave in and re-appointed de Cerralbo as president of the party's top committee.

Leading the Carlists

Some experts believe that as de Cerralbo grew older and tired, de Mella effectively took control of the Carlist party from behind the scenes. The Carlist members of parliament were largely influenced by him. About a third of the party's top committee, the Junta Superior, supported Mellismo. De Mella controlled the propaganda and press sections. His followers also controlled the election and administration sections.

Only El Correo Español remained a struggle with Don Jaime's supporters. But Mellistas were increasingly taking it over. De Mella planned a major change for the party. He hoped Don Jaime could be pushed into a symbolic role, becoming "a king in his own image."

The start of World War I helped de Mella. Don Jaime was under house arrest in Austria and hard to contact. The Mellistas took almost full control of the election strategy. The Carlist election campaigns from 1914 to 1918 clearly showed de Mella's ideas.

De Mella wanted a non-dynastic alliance of ultra-Right groups. He hoped this would create a new, strong Traditionalist party. This party would get rid of liberal democracy and create a Traditionalist system. This strategy led to cooperation with other conservative groups. However, these alliances often ended after elections. Also, some Carlists worried that their local traditions might suffer in such a big alliance.

When World War I started, de Mella's pro-German feelings became a strong campaign. He disliked France and Britain. He wrote many booklets and gave lectures. While he technically supported Spain's neutrality, he actually favored the Central Powers. Don Jaime remained unclear about his stance. Some Carlists close to Don Jaime openly opposed de Mella's pro-German campaign.

Today, there are different views on how important World War I alliances were to de Mella's ideas. Some say it was central, and Mellismo was simply pro-German. Most suggest his views came from his beliefs. They point to his praise of the anti-Liberal German system and his criticism of British and French democratic systems. Some think a Central Powers victory would help the extreme Right take over Spanish politics.

The Party Split

By 1918, de Mella was losing influence. His election alliances didn't bring big gains. The war's outcome made his pro-German stance less relevant. Some regional leaders disagreed with him. De Cerralbo, tired of his divided loyalty, finally resigned.

In early 1919, Don Jaime was released from house arrest in Austria. He arrived in Paris and, after two years of silence, published two statements. These statements, published in Correo Español, criticized unnamed Carlist leaders for not following a neutral policy. They also said the party's leadership would be reorganized.

De Mella and his supporters believed a major conflict was coming. He launched a media counter-attack. He publicly accused Don Jaime of losing his right to rule. De Mella said Don Jaime had been inactive for years. He claimed Don Jaime was hypocritical, supporting the Entente while claiming neutrality. He also said Don Jaime ignored traditional Carlist groups and acted like a dictator. De Mella called Don Jaime's actions a "Jaimada," a coup against Traditionalism.

At first, it seemed both sides were equally strong. But Don Jaime quickly gained the upper hand. His supporters took back control of El Correo Español. He replaced leaders who seemed to be Mellistas with those loyal to him. Many party members who had been unsure about Don Jaime started to support him.

Vázquez de Mella knew he had strong support among parliament members and local leaders. He called for a large meeting, hoping party leaders would help him regain control. Some experts believe he already knew he couldn't control Don Jaime's party. They think his call was a decision to leave and start a new party.

The conflict lasted only two weeks. By the end of February 1919, de Mella openly decided to create his own organization. He set up the Centro de Acción Tradicionalista as his temporary office in Madrid.

Later Life and Retirement

De Mella lost the battle to control Carlism. However, most of its local leaders, members of parliament, and other important figures followed him. But among the regular party members, Mellistas gained little support. It was like an army of generals with few soldiers.

Before the 1919 elections, de Mella formed the Centro Católico Tradicionalista. He hoped this would be a step towards a larger ultra-Right alliance. But the campaign only won 4 seats, and de Mella himself didn't win. He was offered a job in a new government but refused. He said he could never support the 1876 constitution. The 1920 elections were even worse, with Mellistas winning only 2 seats. De Mella lost again.

By 1921, it was clear that de Mella was struggling to organize his own party. He didn't like systematic work. This had been clear during his university years and his time managing Correo Español. He often withdrew and thought about becoming just a thinker, guiding from the sidelines. Meanwhile, more and more of his followers left to join other Right-wing groups.

A big Mellist meeting happened in October 1922 in Zaragoza. But it was controlled by supporters of Víctor Pradera. Pradera wanted a broad conservative alliance, not de Mella's extreme-Right coalition. De Mella didn't attend the meeting. Instead, he sent a letter. He restated his anti-system views and confirmed that a Traditionalist monarchy was his main goal. He said he would work towards this as a theorist, not as a politician anymore.

De Mella did not take part in the new Traditionalist Catholic Party. In 1923, the Primo de Rivera coup stopped all political parties. At first, de Mella might have supported the dictatorship. The press reported he was working to create a new political group. In 1924, Primo de Rivera even met with him.

However, by early 1925, de Mella had doubts about the dictatorship. He saw it as a small version of the big political change the country needed. In January 1925, he called it a "golpe de escoba" (a sweep of the broom), meaning it was not a deep change. Still, he admitted that the government had put some Traditionalist ideas into practice.

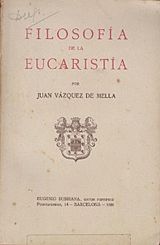

De Mella's last public appearance was in early 1924. He had diabetic health problems and had his leg amputated in the summer of 1924. He remained a public figure, and newspapers reported on his health until early 1925. He died shortly after finishing a philosophical study on the Eucharist. His death was widely discussed in Spanish newspapers.

His Ideas and Philosophy

De Mella's writings are usually seen as political theory. He was influenced by thinkers like Balmes and Donoso Cortés. He was also influenced by Aparisi, other Neo-Catholics, Aquinas, Suárez, and Leo XIII. Some scholars believe he was also greatly influenced by Gil Robles. He did not know the works of famous foreign Traditionalist thinkers.

De Mella is almost always considered a Traditionalist. His ideas are often seen as a classic example of this way of thinking. In his vision, the state (government) is loosely organized and doesn't interfere much. It acts as a light structure above different types of self-governing groups. These groups could be based on jobs, geography, or professions.

Political power belongs to a king who has strong but limited powers. This system is united by a common set of beliefs, defined by Catholic faith and Spanish tradition. De Mella explained the exact details of these ideas very carefully.

The main parts of de Mella's ideas are society, religion, family, regionalism, tradition, and monarchy. However, the most original part of his Traditionalist thought was his idea of society. Many thinkers before him had studied society. They said it wasn't a contract but grew naturally. But most experts agree that de Mella introduced the idea of social sovereignty.

Social sovereignty is different from political sovereignty, which only the king has. It means that communities have the right to govern themselves without outside interference. This includes interference from the king or other communities. Social sovereignty is shown in the Cortes (parliament). Other scholars say this idea was not new, but de Mella developed it into what he called sociedalismo. This means that society is more important than the state. De Mella's ideas led to a big change in Traditionalism. Before him, it focused on the monarchy. After him, it focused on society.

Some scholars highlight de Mella's focus on regionalism. He believed the state should be organized like a federation. Regions would be one type of group between the individual and the nation. Others focus on the nation itself. Everyone agrees that the nation is mainly about tradition. Neither a nation nor a state has its own complete power.

Other key ideas he emphasized were:

- Family: The most important part of society.

- Catholic unity: The basic foundation of the Spanish nation.

- Tradition: A general concept guiding everything.

- Labor: Work and its importance.

- Monarchy: Defined as traditional, hereditary (passed down in families), federative (allowing regional self-rule), and representative.

Even though he was a Carlist most of his life, de Mella didn't strongly emphasize the idea of a specific royal family's right to rule. He believed in "double legitimacy," meaning both the king and the people needed to be legitimate. Since he became a Carlist through thinking, not just family tradition, he later had no problem letting go of the idea of a specific royal line.

A Powerful Speaker and Writer

Most people who knew de Mella were most impressed by his speaking skills. This was true for both young people and experienced politicians. It's often said that when Antonio Cánovas, a famous politician, heard de Mella speak in the Cortes, he was amazed and asked, "Who is that monster?"

De Mella had a powerful effect on large crowds and small groups. People often reported that his speeches made listeners feel very excited. This was surprising because de Mella wasn't physically imposing. He was average height, tended to be overweight, and didn't have a naturally strong voice. But when he spoke, he transformed. People said his body language, eye movements, and gestures combined with his command of words gave him "the majesty of a lion." Some scholars consider de Mella one of the greatest speakers in Spanish parliamentary history.

His speeches were not just shows. Many of them were printed as small books. It's not clear if he improvised or prepared his speeches. But many of his speeches were put together from his private notes. Most published speeches are about 500–800 words, which would be less than a 10-minute talk. Some were up to 1,600 words, lasting almost half an hour. Some scholars compare de Mella to a new type of charismatic public speaker, different from 19th-century leaders.

During his lifetime, de Mella mostly published short pieces in newspapers. These included editorials and essays for El Correo Español and El Pensamiento Español. He also published about ten small books containing his speeches. Near the end of his life, his speeches from parliament were published in two volumes called Discursos Parlamentarios.

Finally, shortly before he died, de Mella finished and published Filosofía de la Eucaristía. This was his only major book published during his life. It was partly a collection of his earlier writings. After his death, a huge number of his writings were published. These included newspaper articles, booklets, speeches, and private papers. They were collected in a 31-volume series called Obras Completas in the 1930s.

This collection is massive. However, it is made up of many small or medium-sized writings, often written for specific occasions. Since there isn't one long, detailed book among them, many editors have tried to combine his ideas. They select pieces they think are most important and group them by topic. This is how de Mella's ideas are usually studied today.

See also

In Spanish: Juan Vázquez de Mella para niños

In Spanish: Juan Vázquez de Mella para niños