Kim Ku facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Kim Ku

|

|

|---|---|

Kim in 1949

|

|

| President of the Provisional Government of the Republic of Korea | |

| In office December 14, 1926 – August 1927 |

|

| Vice President | Kim Kyu-sik |

| Preceded by | Hong Jin |

| Succeeded by | Yi Dong-nyeong |

| In office March 1940 – March 1947 |

|

| Preceded by | Yi Dong-nyeong |

| Succeeded by | Syngman Rhee (President of the Provisional Government) |

| Prime Minister of the Provisional Government of the Republic of Korea | |

| In office October 1930 – October 1933 |

|

| Preceded by | Roh Baek-lin |

| Succeeded by | Yang Gi-tak |

| Personal details | |

| Born | August 29, 1876 T'otkol village, Paegunbang, Haeju, Hwanghae Province, Joseon |

| Died | June 26, 1949 (aged 72) Gyeonggyojang, Jongno District, Seoul, South Korea |

| Cause of death | Assassination |

| Resting place | Hyochang Park, Yongsan District, Seoul, South Korea |

| Nationality | Korean |

| Political party | Korea Independence Party |

| Children |

|

| Religion | Methodism formerly Cheondoism, Buddhism |

| Korean name | |

| Hangul |

김구

|

| Hanja | |

| Revised Romanization | Gim Gu |

| McCune–Reischauer | Kim Ku |

| IPA | [kim.ɡu] |

| Art name | |

| Hangul |

백범

|

| Hanja | |

| Revised Romanization | Baekbeom |

| McCune–Reischauer | Paekpŏm |

| IPA | [pɛk.p͈ʌm] |

| Birth name | |

| Hangul |

김창암

|

| Hanja | |

| Revised Romanization | Gim Chang(-)am |

| McCune–Reischauer | Kim Ch'angam |

| Courtesy name | |

| Hangul |

연하

|

| Hanja | |

| Revised Romanization | Yeonha |

| McCune–Reischauer | Yŏnha |

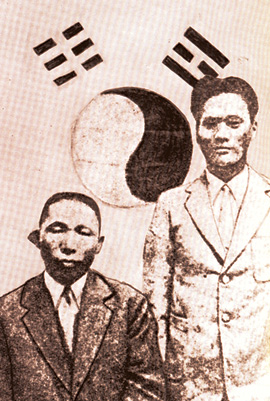

Kim Ku (Korean: 김구; August 29, 1876 – June 26, 1949), also known by his art name Paekpŏm, was a very important Korean politician. He was a key leader in the Korean independence movement against Japan. He led the Korean Provisional Government (KPG) for several terms. After 1945, he worked to unite Korea. In South Korea, many people see Kim Ku as one of the greatest figures in Korean history.

Kim was born into a poor farming family during the Joseon period. During this time, Korea faced many challenges, including peasant uprisings and interference from powerful countries like Japan. Kim spent most of his life fighting for Korea's freedom. He was even jailed by Japanese authorities for his actions. He lived in China for 26 years, working in the KPG and cooperating with the Republic of China. While there, he started and led groups like the Korean Patriotic Organization and the Korean Liberation Army. He faced many attempts on his life and even planned some actions himself, including an attempt on the Japanese Emperor Hirohito. After Japan surrendered in World War II in 1945, Kim returned to Korea. He tried to stop Korea from being divided into two countries.

However, in 1949, just before the Korean War began, Kim was killed by a Korean lieutenant named Ahn Doo-hee.

Today, Kim is mostly celebrated in South Korea. But some people have criticized him. In 1896, Kim was involved in a fight where a Japanese man died. Kim believed this man might have been connected to the Japanese military or the killing of Empress Myeongseong. The man is now thought to have been a civilian merchant. Kim also helped plan attacks against Japanese military and government officials. In North Korea, his legacy is viewed differently because he was against communism.

Contents

- Early Life and Education

- Early Activism (1893–1905)

- Independence Activities in Korea (1905–1919)

- Exile in Shanghai (1919–1932)

- Escape and New Beginnings (1932–1937)

- Second Sino–Japanese War (1937–1945)

- Return to Korea and Reunification Efforts (1945–1949)

- Death

- Legacy and Honors

- Personal Life

- Images for kids

Early Life and Education

Kim was born Kim Ch'ang-am on August 29, 1876, in a village called T'otkol in Haeju City, Hwanghae Province, Korea. He was the only child of two farmers, Kwak Nak-won and Kim Sun-yŏng. His family was poor and not well-educated.

When he was two, Kim had smallpox, which left scars on his face. His family wanted him to get an education to escape poverty. Around age nine, his parents tried to enroll him in a local school to prepare for government exams. But schools turned him away because of his family's lower social class. He finally started learning at age twelve with a tutor.

In 1888, when Kim was 12, his father became paralyzed. His mother sold everything to find a doctor. Kim helped pay for his own living by cutting wood. His father eventually recovered somewhat. His mother worked hard weaving and farming to pay for Kim's school supplies.

In 1892, at 16, Kim took the government exams but failed. He saw that rich students were cheating and bribing officials, which made him upset. He stopped formal schooling and spent time studying on his own.

Early Activism (1893–1905)

Joining the Donghak Movement

In 1893, Kim joined the Donghak movement. This group wanted to improve Korea by changing old traditions, bringing in democracy, and removing foreign influence. Within a year, Kim became a well-known figure in the movement. He also changed his name to Kim Ch'ang-su.

In 1894, a peasant revolution began. Kim, at 17, became a leader of a Donghak army group of about 700 soldiers. His troops attacked a fort in Hwanghae province, but they were defeated by government and Japanese forces. Kim managed to escape.

Journey and Encounter

In 1895, Kim joined General An T'ae-hun's Royal Army. General An liked Kim and even helped his parents. Kim also met An's son, An Jung-geun, who later became famous for fighting against Japan.

Kim also learned from a scholar named Ko Nŭng-sŏn. Ko taught Kim that Japan was a big threat to Korea. This made Kim want to visit Qing China to ask for help protecting Korea.

Kim and a friend planned to travel to China. On their way, they joined a group of fighters called the Righteous armies. They attacked a fortress, but it failed, and Kim escaped.

The Ch'ihap'o Incident (1896)

In February 1896, Kim decided to return home. While staying at an inn, he met a man he thought was a Japanese spy, possibly involved in the killing of Empress Myeongseong. Kim attacked the man, and in the struggle, the man died. Kim believed the man was a Japanese army officer. However, it is now generally thought the man was Tsuchida Josuke, a Japanese merchant.

Japanese officials ordered Kim's arrest.

First Imprisonment (1896–1898)

Kim was arrested in June 1896 and held in jail. He was treated poorly by Japanese authorities at first, but later, Korean prison staff treated him with respect. Important Koreans asked for his release and collected money for his bail.

Kim was almost executed, but King Gojong read about Kim's reasons for his actions and did not approve the death sentence. So, Kim escaped death.

In prison, Kim read Western history and science books. He was very impressed and changed his mind about Western ideas. He decided that new ideas could help Korea. He also taught many fellow prisoners how to read and write.

Escape and Monkhood (1898–1899)

On March 19, 1898, Kim and other prisoners escaped. His father was arrested in his place for a year. Kim walked over 800 kilometers across Korea.

He later became a Buddhist monk at Magoksa temple, taking the name Wŏnjong. He didn't truly believe in Buddhism or enjoy the monk's life. In 1899, he left the temple and reunited with his parents.

Returning Home (1900–1905)

After returning home, Kim visited his old teacher Ko Nŭng-sŏn, who was upset that Kim had accepted foreign ideas. Kim felt Ko's ideas were old-fashioned.

Kim's father died in December 1900. In February 1903, Kim became a Protestant Christian. In December 1904, he married Ch'oe Chun-rye. They had a daughter in 1906, but she died within a year.

Kim worked as a farmer and became the principal of several schools, teaching subjects like middle school math.

Independence Activities in Korea (1905–1919)

In November 1905, Korea became a protectorate of Japan. This meant Japan controlled Korea's foreign affairs. In 1910, Japan formally took over Korea.

After the 1905 treaty, Kim went to Seoul to protest. He and other future independence leaders gave speeches, asking Emperor Gwangmu to cancel the treaty. But the protests were stopped by Korean authorities. Kim decided that Koreans needed to become smarter and more patriotic. He went back home and focused on teaching.

In 1907, Kim joined the New People's Association, an organization dedicated to Korean independence. He became the leader of its Hwanghae branch.

In 1909, after An Jung-geun killed a Japanese official, Kim was arrested and jailed for about a month. He was released when no evidence linked him to the murder.

Third Imprisonment (1911–1915)

In January 1911, Japanese authorities arrested over 700 Koreans, accusing them of planning to kill the Japanese Governor-General. Kim was arrested because of his connection to An Jung-geun's cousin. This event was called the "105-Man Incident." Kim was sentenced to 15 years in prison.

He spent two and a half years in Seodaemun Prison, where he was beaten.

In 1912, while in prison, Kim changed his name to "Kim Ku." This name means "nine" and was chosen to be simple. His art name, "Paekpŏm," means "ordinary person." These names showed Kim's belief that even ordinary people needed to fight for Korea's freedom.

He was later moved to an Incheon prison.

Release from Prison (1915–1919)

Kim did not serve his full sentence. His sentence was reduced due to pardons from the Japanese government. He spent his remaining time doing hard labor.

In 1915, Kim was released on parole. He wanted to teach again, but as a former political prisoner, he couldn't. Instead, he became a farmer.

Exile in Shanghai (1919–1932)

On March 1, 1919, a nationwide non-violent protest called the March 1st Movement took place. Japan violently stopped it, leading to many deaths and arrests. Kim and other Korean nationalists left the country to escape. This movement greatly boosted the Korean independence movement.

Early Provisional Government (1919–1926)

Kim traveled to Shanghai, China, to join the Provisional Government of the Republic of Korea (KPG). He arrived on April 13, 1919, and became the police commissioner. He stayed in Shanghai for 13 years. In September 1919, Syngman Rhee was elected the first KPG president, and Kim became Chief of Staff.

The KPG faced many challenges. They constantly had to avoid Japanese spies. Kim executed some people who betrayed the movement. The government moved often to avoid being caught. Kim and others often held many different jobs within the KPG.

The KPG also struggled with money. Most of their funds came from Koreans in America. They often couldn't pay rent or salaries, which caused problems within the group.

The KPG also had political disagreements between its left and right-leaning members. Kim was aligned with the pro-American Christian group.

Kim's family life was hard. His wife died in 1924, and he couldn't visit her in the hospital. He temporarily placed his youngest son, Shin, in an orphanage. Later, his mother and both sons returned to Korea.

Leading the Government (1926–1930)

In March 1925, Syngman Rhee was removed from his position as president. After that, leadership changed quickly, with many people serving as head of state for only a few months.

From December 14, 1926, to August 18, 1927, Kim Ku served as the head of the KPG. He changed the president's role to "Chairman of the State Council Directory," where the chairman was the "first among equals." This helped his term last longer than others. After his term, he became the Minister of Internal Affairs again.

In May 1929, Kim finished the first part of his autobiography, Diary of Kim Ku. In 1930, Kim started the Korea Independence Party to unite the right-leaning members of the government.

Korean Patriotic Organization (1931–1932)

In 1931, Kim founded the Korean Patriotic Organization (KPO). This group was created to take strong action for independence and improve relations between China and Korea. The KPO received a large part of the KPG's budget.

On January 8, 1932, KPO member Lee Bong-chang tried to kill Emperor Hirohito in Tokyo. Lee was later executed.

On April 29, 1932, another KPO member, Yun Bong-gil, threw a bomb at Japanese officials in Shanghai. Many Japanese leaders were killed or injured. This event made Kim Ku famous and also made him a target for the Japanese.

Escape and New Beginnings (1932–1937)

To protect other Koreans, Kim publicly took responsibility for the KPO's actions. The Japanese government offered a huge reward for his capture.

Kim had to flee across China. An American missionary, George Ashmore Fitch, helped Kim hide in his house in Shanghai. When the Japanese got close, Kim escaped by pretending to be an American couple with Fitch's wife.

Hiding in Jiaxing and Haiyan (1932)

A Chinese supporter helped Kim escape to a hiding place in Jiaxing. The building had secret features like hidden doors. Kim pretended to be a Cantonese man.

Other KPG members moved their headquarters to Hangzhou. Kim resigned from the KPG temporarily because he couldn't perform his duties while on the run.

Later, Kim moved to another hiding place in Haiyan county. To help him blend in, it was suggested he marry a local Chinese woman. He chose Zhu Aibao, the 20-year-old owner of a boat he often rode. They lived together on her boat for about five years, though they never officially married.

This time in Haiyan was one of the most peaceful periods of his life. He enjoyed being outdoors and spending time with Zhu. He felt bad about deceiving her about his true identity. He never saw her again after November 1937.

Support from China (1933–1937)

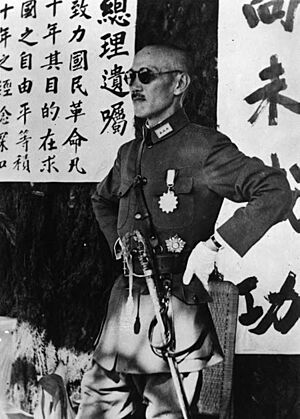

Around July 1932, Kim asked to meet with Chiang Kai-shek, the leader of China. Kim wanted help to train Korean fighters. Chiang agreed to meet him.

In September 1932, they met. Kim asked for a large sum of money to cause trouble for Japan in Korea and Manchuria. After some talks, Chiang agreed to give Kim money each month and hide him from the Japanese. He also allowed Kim to train Korean resistance fighters at a military academy in Nanjing. Kim was very happy to have a steady source of income and began recruiting young Korean fighters.

Training Independence Fighters (1934–1935)

In February 1934, Kim helped manage a training class for Korean army officers near Luoyang. The class was kept secret from the Japanese by pretending to be an all-Chinese class. They trained in tactics, weapons, and other military skills. There were 92 students, including Kim's eldest son, In.

The training had some problems, including disagreements between left- and right-leaning Korean groups. Kim's funding from China was cut in half, and Japanese authorities started to find their training location. So, they had to move.

In December 1934, Kim created a special forces group for the remaining trainees. On April 9, 1935, the school closed after about a year.

Family Reunion (1934)

After the training started, Kim invited his mother and sons to China. His stable income and protection from China's government made this possible. In April 1934, Kim reunited with his mother and two sons in Jiaxing for the first time in nine years. They moved to Nanjing, where Kim had prepared a house for them.

Challenges in the Provisional Government (1933–1935)

As KPG members fled Shanghai, the independence movement faced difficulties. Much of the KPG stopped working, and internal disagreements grew.

In 1933, Kim's Independence Party voted to remove absent leaders, but kept Kim out of respect. Even though he had resigned, he was still important to them.

The KPG moved its headquarters several times. In 1934, Kim lost his seat in the Provisional Assembly after almost 15 years.

In 1935, a major split happened in the KPG. Many members, including Kim Won-bong, wanted to dissolve the KPG and create a single-party government. This led to the creation of the Korean National Revolutionary Party (KNRP) under Kim Won-bong. Kim Ku was against this, believing one-party rule wouldn't work. He rejoined the KPG and united the remaining members into the Korean National Party (KNP). The KNP was more right-leaning and allied with the United States, while the KNRP was left-leaning and allied more with the Soviet Union. The two parties competed fiercely.

Second Sino–Japanese War (1937–1945)

In July 1937, the war between China and Japan began. The KPG saw this as a big chance to gain independence. They planned to create a large army, expecting funding from China. However, these plans failed because they had to keep moving as China's government retreated.

Fleeing to Changsha (1937–1938)

On August 17, 1937, the different KPG parties finally united. Japan began bombing Nanjing. Kim helped coordinate the evacuation of about 120 KPG members and their families. He worried about the safety of An Jung-geun's widow and felt sad about leaving Zhu Aibao, his 'wife'. Kim took his younger son and mother to Changsha. Soon after they left, the terrible Nanjing Massacre happened.

By December 1937, the KPG was in Changsha. Money was tight, but they managed by living together. Kim felt safe enough to openly use his real name for the first time in China. His mother celebrated her 80th birthday. She asked him to use any money for her party to buy a pistol for Korean fighters instead.

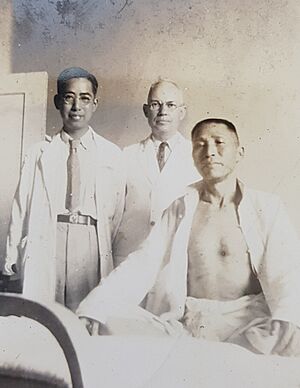

Shot in Changsha (1938)

Relationships between the parties improved in Changsha. On May 7, 1938, Kim and other leaders were having dinner when a young man burst in and shot them. Kim, Hyŏn Ik-ch'ŏl, Ryu Tong-yŏl, and Ji Cheong-cheon were shot. Everyone recovered except Hyŏn, who died that day.

The shooter was a 30-year-old man named Yu Chin-hong. He was arrested but later escaped. When Chiang Kai-shek heard about the shooting, he sent a telegram to Kim's hospital. Kim didn't remember what happened until a month later when he learned the truth.

Arriving in Chongqing (1938–1940)

After leaving the hospital, Kim managed the relocation of about 400 KPG members and their families. Changsha became unsafe due to Japanese air raids. The KPG eventually moved to Chongqing to be with China's government. They faced constant danger from the Japanese. Kim arrived in Chongqing in October 1938.

In early 1939, Kim's mother became ill while traveling and died on April 26, 1939. Her last wish was for Kim to succeed in his independence work and bury her ashes in their homeland. She is now buried in South Korea.

Life in Chongqing was difficult. The city was crowded, and Japanese bombings were frequent. Kim often had to find money to build or repair homes for KPG members. Many Koreans died from illnesses due to poor conditions. Kim's eldest son, In, died in 1945. Kim himself suffered from a vitamin deficiency.

The KPG moved its offices four times because of bombings. Their third office was used for four years, the longest they stayed in one building since Shanghai. While there, Kim finished the second part of his autobiography, Diary of Kim Ku.

Efforts to Unite the Independence Movement (1939–1940)

In Chongqing, Kim worked to unite the different Korean parties. The war had changed his mind about working together. China's leaders also wanted the Koreans to stop fighting among themselves.

Kim especially wanted to unite with Kim Won-bong, whose KNRP had successfully raised an army called the Korean Volunteers Army.

In 1939, they began serious talks about merging. Kim proposed a single party, while the left-leaning groups wanted a multi-party government. They released a joint statement listing shared goals for a free Korea, including gender equality and free education. However, talks broke down over who would lead the army and how much they should work with China's government. Soon after, World War II began.

Kim blamed the left-leaning parties for the failure of the talks. He warned that if the right and left didn't unite, Korea would face bloodshed in the future. China's government became more involved, pushing for unification. They suggested that the KPG operate in one part of China and the KNRP in another. This plan was accepted.

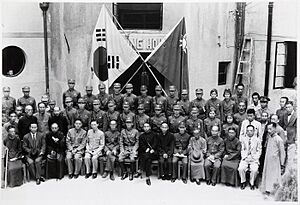

On March 13, 1940, the KPG President Lee Dong-nyeong died. Kim became the new head of government. On April 1, the parties within the KPG united into the Korean Independence Party. Kim was elected Chairman of the Executive Committee.

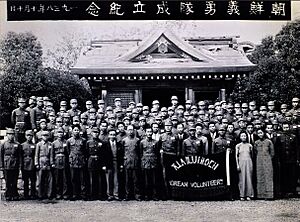

Creating the Korean Liberation Army (1939–1942)

On November 11, 1939, the KPG announced a plan to create a large army. The plan was very ambitious and expensive. When Kim took charge, he took a more realistic approach.

On April 11, 1940, Chiang Kai-shek approved Kim's idea for a KPG army, but with limited funding. Chiang wanted the army to be under China's command, but Kim wanted it to be more independent. China pulled out of the deal, but Kim moved forward anyway.

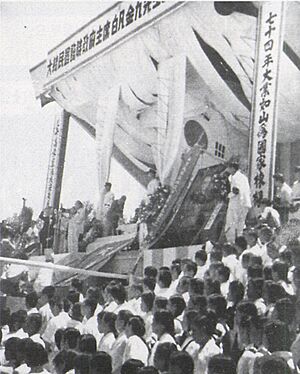

On September 17, 1940, the Korean Liberation Army (KLA) was officially formed. General Ji Cheong-cheon became its commander. A ceremony was held to make the army seem strong and important.

The KLA became a symbol for Koreans living abroad, and donations increased. Kim and others believed that Koreans on the peninsula would rise up against Japan and support the KLA.

In September 1940, Kim was reelected as head of government and held this position until 1945. The KPG changed its constitution to give the chief executive more power to manage the army. Kim became the Chairperson of the State Affairs Commission, with more authority. The KLA announced its plan to switch from guerrilla warfare to regular battles. They moved their headquarters and began secret operations, recruiting young people.

Challenges with Chinese and US Support

China's government delayed formally recognizing the KLA and providing support, which frustrated Kim. The KLA was growing, but soldiers were idle and lacked funds. China even tried to restrict KLA activities. However, they formally recognized the KLA in May 1941. Aid was still slow, partly due to interference from Kim Won-bong, who saw the KLA as competition.

The US government also hesitated to support the KPG. Kim sent many letters to US President Franklin D. Roosevelt, asking for formal ties, but they were ignored. The US was cautious because of the ongoing Pacific War and disagreements among Koreans. In December 1941, the KPG declared war on Japan.

The US rejected proposals to recognize the KPG. In 1942, China proposed merging Korean groups into an army that would enter Korea, and then the US would recognize the KPG. But the US only supported the army, not full recognition of the KPG.

In 1942, the Allies secretly discussed putting Korea under a temporary international control after the war. Rumors of this angered the Korean independence movement. In November 1943, the US, UK, and China announced the 1943 Cairo Declaration, stating that Korea "in due course" would "become free and independent." While there was initial excitement, the phrase "in due course" worried Kim, as it could mean temporary control. Kim told a reporter that if Korea wasn't immediately independent after Japan's surrender, they would continue fighting.

Unification Efforts (1942)

In May 1941, Kim Won-bong's KNRP began joining the KPG, but this caused many conflicts.

In early 1942, Kim learned that China's government was talking with Kim Won-bong about merging the Korean Volunteers Army into the KLA. Kim Won-bong agreed, if he could become the KLA's deputy commander.

On May 13, the KPG approved the merger. This decision made both sides unhappy. Kim Ku protested China's interference. China's government then reduced funding and placed Chinese officers in KLA positions, making military activities difficult.

On October 9, Chiang Kai-shek softened his stance, offering funding to the KPG and promising Korea's independence. On October 11, China's government helped unite the various parties into a coalition. The KNRP had a weak showing in KPG elections. Kim and his party were happy, seeing this as a victory.

Conflicts and Agreements (1943–1945)

Alleged Assassination Attempt

On May 15, 1943, the Independence Party announced an assassination attempt on Kim and other leaders. They claimed that two men tried to steal a handgun to kill Independence Party leaders and increase KNRP power.

The two men were arrested but later released due to lack of evidence. This incident hurt the KPG's reputation and increased internal tensions. The KNRP claimed it was a false flag operation. They also accused Kim of holding back funds from them, which embarrassed Kim.

Resignation and Return

After a failed attempt by Chiang Kai-shek to mediate, Kim and six others in the State Council resigned on August 31. This stopped KPG activities. On September 21, they withdrew their resignations and returned.

In October, a tense KPG meeting aimed to change the constitution to include the KNRP. The KNRP tried to remove Kim and the current government. Debates were so fierce that the meeting lasted until April 1944. China's government threatened to stop funding both sides if they didn't compromise.

Finally, on April 11, they agreed on the constitutional change and not to remove Kim. Kim was reelected head of government, and Kim Won-bong became head of the Armed Forces.

Agreement with China

On September 5, 1943, Kim met with Chiang Kai-shek and asked for public recognition of the KPG, more independence for the KLA, and help for Koreans in Central Asia. Most requests were denied or delayed. KLA funding remained very low.

The KPG decided to seek relationships with other Allied governments. Kim continued sending letters to President Roosevelt, offering KPG military support. The KLA even sent soldiers to fight for the British Indian Army.

Finally, on May 1, 1945, the KPG gained full control over the KLA through an agreement with China. This allowed the KLA to work more freely with other Allied countries.

Eagle Project (1945)

In September 1944, the KLA began planning with the US Office of Strategic Services (OSS) to send Korean guerrillas to Korea. This plan was called the Eagle Project. Kim met with OSS officials in April 1945.

Training began in May. Kim went to Xi'an to meet General Donovan and the first class of graduates. They met on August 7, 1945. Kim gave Donovan a telegram for President Harry S. Truman, hoping the US would recognize the KPG.

However, around this time, the US dropped atomic bombs on Japan, and Japan surrendered. Less than a month later, Truman closed the OSS. Kim later wrote that he was very happy with the meeting, but felt sad that years of preparing for war were now in vain. He worried that Korea's voice on the international stage would be weak because they hadn't directly fought in the war.

Return to Korea and Reunification Efforts (1945–1949)

On August 10, 1945, Kim learned that Japan had surrendered.

Kim and the OSS planned for KLA soldiers to return to Korea for reconnaissance. Kim returned to Chongqing on August 18. However, the Eagle Project was soon ended.

The liberation of Korea did not unite the Korean groups in exile. Left- and right-wing groups in Chongqing made separate plans for Korea's future. Meanwhile, Syngman Rhee was chosen by the US as a preferred leader for occupied Korea.

Kim returned to the Korean peninsula in December 1945.

Meeting Kim Il Sung (1948)

In April 1948, Kim went to North Korea. As it became clear that Korea would be divided, Kim led a team of independence activists to Pyongyang to talk about unification with Kim Il Sung, who later became the leader of North Korea.

Kim Ku was still against communism, but he softened his stance to try and get Kim Il Sung to agree to unification. Some Koreans at the time also didn't trust the US. Kim Il Sung later claimed that Kim Ku begged for forgiveness for his past anti-communist actions, but some South Korean scholars doubt this.

Many people at the time and critics today were skeptical of Kim Ku's efforts to appease Kim Il Sung. Kim returned to the South worried that North Korea would easily win if it invaded.

In 1948, Kim was nominated to be the first president of South Korea. However, he was defeated by Syngman Rhee. Kim did not approve of his nomination because he was strongly against the idea of separate governments in North and South Korea.

Death

On June 26, 1949, Kim was reading poetry in his office when he was killed by Lieutenant Ahn Doo-hee.

Years later, in 1996, Ahn Doo-hee was murdered by Park Gi-seo, a bus driver who admired Kim Ku.

Reason for Assassination

Ahn Doo-hee claimed he killed Kim because he believed Kim was working for the Soviet Union.

Some sources suggest another reason was Kim Ku's possible connection to the killing of Song Jin-woo, a leader who worked closely with the American military government.

In 1992, Ahn's confession was published, stating that the assassination was ordered by Kim Chang-ryong, who was in charge of national security for Syngman Rhee. In 2001, declassified documents showed that Ahn had worked for the US Counter-Intelligence Corps, leading to questions about American involvement. However, some have questioned the evidence for these claims.

Legacy and Honors

Diary of Kim Ku

His autobiography, Diary of Kim Ku, is a very important source for studying the Korean independence movement. The Korean government recognized it as a cultural treasure in 1997.

Honors and Awards

A street in Seoul, Baekbeom-ro, and a park on Namsan mountain, Baekbeom Square Park, are named after him.

In 1962, Kim was given the Republic of Korea Medal of Order of Merit for National Foundation, South Korea's highest civilian honor. In 1990, North Korea also gave him the National Reunification Prize.

Many universities, like Harvard University and Tufts University, have special positions or forums named after Kim Ku to study Korean topics. In 2009, Brown University received materials to start the "Kim Koo Korean Collection."

The Kim Koo Museum opened in Seoul in 2002. Several items connected to Kim Ku are considered cultural heritage in South Korea, including a South Korean flag with his writing, his bloodied clothes from his assassination, and his calligraphy.

In 2023, Starbucks Korea donated a piece of Kim's handwritten calligraphy and released special tumblers showing it.

Debate on "Terrorism"

For many years, there has been a debate about whether Kim Ku can be called a "terrorist."

In 2007, a professor described Kim's Korean Patriotic Organization (KPO) as a "terrorist group." Students disagreed, pointing out that Kim did not carelessly target civilians. The professor later withdrew the description, saying the word "terrorism" carried too much unintended meaning.

Some South Korean conservatives have also used this term. In 2009, a textbook called Kim a "terrorist" and a "left-wing politician who was against the founding of the Republic of Korea." This was different from how most people described his actions, which were seen as "passionate struggle" and "independence activism." In 2014, a government-approved history textbook that described Kim as a terrorist was used in a small number of high schools.

Some scholars note that the debate over this term has caused conflict in relations between Japan and South Korea.

Personal Life

Kim was married to Ch'oe Chun-rye (March 19, 1889 – January 1, 1924) until she died in Shanghai at age 34 from pneumonia. She was buried in the Shanghai French Concession.

Children

Kim had five children, three daughters and two sons. Only his sons survived past childhood. His daughters died young.

His elder son, Kim In (1917–1945), joined his father in Shanghai in 1920. He returned to Korea in 1927 and then to China in 1934. He worked in the Provisional Government's army. In 1940, he married Susanna Ahn, the niece of An Jung-geun. They had one daughter. Kim In died at age 27 in 1945 from tuberculosis.

His younger son, Kim Shin (1922–2016), became the Chief of Staff of the Korean Air Force and held other political roles. After retiring, he managed the family's foundations. He died at age 93.

Images for kids

| Victor J. Glover |

| Yvonne Cagle |

| Jeanette Epps |

| Bernard A. Harris Jr. |