Knole facts for kids

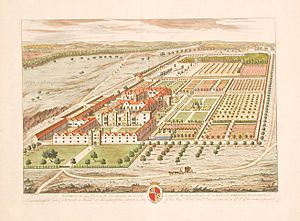

Quick facts for kids Knole |

|

|---|---|

Knole in 2009

|

|

| Type | Country house |

| Location | TQ53955420 |

| Area | Kent |

| Built | Mostly 1455–1608 |

| Architectural style(s) | Jacobean architecture with other earlier and later styles |

| Owner | National Trust |

|

Listed Building – Grade I

|

|

| Official name: Knole | |

| Designated | 14 April 1951 |

| Reference no. | 1336390 |

| Official name: Knole | |

| Designated | 1 May 1986 |

| Reference no. | 1000183 |

| Lua error in Module:Location_map at line 420: attempt to index field 'wikibase' (a nil value). | |

Knole (pronounced "Nole") is a huge English country house and was once a palace for an Archbishop. It is owned by the National Trust, a charity that protects historic places. Knole is located in Knole Park, a large 1,000-acre park near Sevenoaks in west Kent. It is one of England's biggest houses, covering about 4 acres.

The house you see today was mostly built in the mid-1400s. It had big additions in the 1500s and especially in the early 1600s. Knole is a "Grade I listed building," which means it's very important. It shows a mix of styles from the late Middle Ages to the Stuart period. In 2019, a big project called "Inspired by Knole" finished. It helped fix up the buildings and protect the amazing collections inside. The surrounding deer park has also been looked after for over 400 years.

History of Knole House

Where Knole is Located

Knole is at the southern end of Sevenoaks, in a part of Kent called the Weald. The land around Sevenoaks has sandy soil and lots of woodland. In the Middle Ages, this woodland was used for feeding pigs, grazing animals, and getting timber. Knole estate is on well-drained land. It was close enough to London for its owners to easily travel for important government work. King Henry VIII even said it was on "sounde, parfaite, holesome grounde" (healthy, perfect ground). It also had plenty of fresh spring water.

The small hill (knoll) in front of the house helps protect it. The wooded landscape provided wood and grazing for food for a large household. It was also perfect for a deer park, which was created before the end of the 1400s. There's a dry valley near the house that was used for deer races and hunts.

Early Owners of Knole

The first known owner of the main part of the estate was Robert de Knole in the 1290s. We don't know much about his property there. Other families, the Grovehursts and Ashburnhams, owned it until the 1360s. The "manor of Knole" was first mentioned in 1364.

In 1419, Thomas Langley, who was the Bishop of Durham, bought the estate, which was about 800 acres. By 1429, he had made it even bigger, to 1,500 acres. The Langley family owned it until the mid-1440s. Then, James Fiennes, 1st Baron Saye and Sele, bought it. He also made the estate larger, sometimes by forcing people to sell their land. For example, in 1448, one person was forced to sell land to Saye "on threat of death." This kind of forced land transfer happened again later, like between Archbishop Thomas Cranmer and Henry VIII.

Lord Saye and Sele started building at Knole, but he died in 1450 before it was finished. He was very powerful in Kent, and his actions helped cause the Jack Cade Rebellion. He was executed because of the rebels' demands when they reached London.

Archbishop Bourchier's House

James Fiennes's son, William, sold Knole in 1456 to Thomas Bourchier, who was the Archbishop of Canterbury. He already had a big property nearby, Otford Palace, but he liked Knole's drier, healthier location. Archbishop Bourchier likely started by fixing up the existing house. Between 1456 and 1486, he oversaw a lot of building work on the current house. The house was ready for him to stay in by 1459. He spent more and more time there as he got older, especially after 1480. In 1480, Thomas Cardinal Bourchier (he became a Cardinal in 1473) gave the house to the Archdiocese of Canterbury.

Over the next few years, Knole House grew even larger. A big courtyard, now called Green Court, and a new entrance tower were added. For a long time, people thought these were built by a later archbishop. However, studies by Alden Gregory suggest that Bourchier was responsible. He used the peaceful time after King Edward IV returned to power in 1471 to invest more in his property.

Knole in the Tudor Period

After Cardinal Bourchier died in 1486, the next four archbishops lived at Knole: John Morton, Henry Deane, William Warham, and Thomas Cranmer. Sir Thomas More even performed in plays there for Archbishop Morton. King Henry VII visited sometimes, in 1490.

Cardinal Bourchier had fenced off the park to create a deer park. King Henry VIII often visited Archbishop Warham to hunt deer. After Warham died, and before a new archbishop was chosen, Henry used Knole and his other property at Otford as homes for his daughter Mary. This was during the time he was trying to divorce her mother, Catherine of Aragon. Mary stayed at Knole from November 1532 to March 1533.

Thomas Cranmer, the next archbishop, took over all the church's properties. But these properties came with many debts and complicated land issues. This was also a time when many church lands were being taken over by the Crown. Because of this, Cranmer could not refuse King Henry VIII's repeated demands to exchange land. This happened between 1536 and 1546. In 1537, the manor of Knole and several other church lands were "exchanged" with Henry VIII. In return, Cranmer received former abbeys and priories.

Knole was given to Edward Seymour, 1st Duke of Somerset, in August 1547, when his nephew Edward VI became king. But after Somerset was executed in 1549, Knole went back to the Crown. Queen Mary later gave it back to her Archbishop of Canterbury, Cardinal Reginald Pole. But when they both died in 1558, the house returned to the Crown again.

In the early 1560s, Elizabeth I gave Knole to Robert Dudley, 1st Earl of Leicester. He returned it in 1566, but he had already leased it to Thomas Rolf for 99 years. The lease said the landlord (Dudley) would do all repairs and could stay in the main house whenever he wanted. The tenant could also change or rebuild the house. Meanwhile, Elizabeth might have given the estate to her cousin Thomas Sackville, who was then called Lord Buckhurst.

There was a lot of competition for Knole. Rolf died soon after, and a rich local lawyer named John Lennard bought the rest of the lease. Lennard had been buying properties around Sevenoaks. Lord Buckhurst was also trying to get the lease. Knole became a very important addition to Lennard's land in 1570. However, Buckhurst still had some rights, including owning some of the deer in the park. John Lennard moved to Knole, and his son Sampson, who was married to Lord Dacre's daughter, got a sub-lease. Knole was very valuable to Sampson, bringing him good income in 1599.

One of Sampson Lennard's daughters, Margaret, married Sir Thomas Waller. They lived at Knole, and Margaret gave birth to their son William there, probably in 1598. William later became Sir William Waller and was a leader in the English Civil War for the Parliament side.

Knole in the Early Stuart Period and the Sackville Family

Since Robert Dudley had given a 99-year lease, Thomas Sackville had to buy out the remaining 51 years of the lease for £4,000 in 1603. Lennard was happy to sell because he had debts and wanted to gain the Dacre title, which he did in 1604 from a group led by Thomas Sackville. This was probably not a coincidence. Sackville's family, the Earls and Dukes of Dorset and Barons Sackville, have owned or lived in Knole ever since.

Thomas Sackville, then Lord Buckhurst, had thought about building a house elsewhere. But he couldn't ignore Knole's advantages: good spring water, plenty of timber, a deer park, and being close to London. He immediately started a huge building project. This was supposed to be done in two years, with about 200 workers. But records show that a lot of money was still being spent even in 1608–1609. Sackville had a successful career under Queen Elizabeth and then became the Lord High Treasurer for King James VI and I. He had the money for such a big project. He might have hoped the King would visit Knole after his renovations, but it seems the King never did. Thomas Sackville himself died in April 1608, at about 72, while the building work was still going on.

Thomas Sackville's grand house, like others from the Jacobean period, was a sign of his wealth. Unlike almost any other large English house, Knole still looks much as it did when Thomas died. It has stayed "motionless" since the early 1600s.

Thomas's son, Robert Sackville, 2nd Earl of Dorset, inherited the titles and estates. He described his father's work on Knole, saying it was "newly rebuilt" with many buildings, courts, gardens, and ponds. He said the cost of building and furnishing it was at least £30,000.

The 2nd Earl did not enjoy Knole for long, as he died in January 1609. His two sons, Richard Sackville, 3rd Earl of Dorset and then Edward Sackville, 4th Earl of Dorset, inherited the estate. None of these earls lived at Knole permanently. The 3rd Earl mostly lived at court, but he kept his hunting horses and hounds there.

The wife of the 3rd Earl, Lady Anne Clifford, lived at Knole for a while during a disagreement about her inheritance. A list of the household at Knole from this time still exists. It names the servants and where they sat for dinner. The list includes two African servants, Grace Robinson, a laundry maid, and John Morockoe, who worked in the kitchen. In 1623, a large part of Knole House burned down.

Knole During the Civil War and Later

Edward Sackville, the 4th Earl, was a moderate supporter of the King. In the summer of 1642, he and his cousin Sir John Sackville were suspected of hiding weapons and preparing local men to fight for King Charles I during the English Civil War. On August 14, 1642, Parliament sent soldiers to seize these weapons from Knole. Sir John was arrested.

The soldiers then went to Knole. The Earl of Dorset's manager said they caused £186 worth of damage and took away "five wagonloads" of arms. However, many of these weapons were old and not useful for soldiers. Edward accepted the damage to Knole as part of the war.

Parliament set up County Committees to govern areas they controlled. For about a year, the Kent Committee was based at Knole. They also kept the county's money there, along with a bodyguard of 75 to 150 men. The Committee used the Knole estate for supplies and even rented fields from local landowners. They held meetings in the room now called Poets' Parlour. They spent money on sheets, table linen, carpets, silverware, and other items. They also removed the rails and leveled the ground in the chapel, showing some of the religious changes happening during the war. The committee moved away from Knole by April 1645.

When Edward Sackville died in 1652, his son Richard inherited the earldom and estates, but they were heavily in debt because of fines from Parliament for his father's role in the Civil War. Richard quietly worked to reduce the debt. His marriage to Lady Frances Cranfield was important for Knole. When her brother died, she inherited other estates, and many valuable items from those estates were moved to Knole. These included copies of the Raphael Cartoons and many portraits and pieces of furniture. Richard died at Knole in 1677. His son, Charles Sackville, 6th Earl of Dorset (1643–1706), sold some of the other estates in 1701, and more contents were moved to Knole, making its collection even richer. Charles and John Sackville, 3rd Duke of Dorset are seen as the two main collectors who built Knole's amazing collections.

Charles was an important person in the royal court. He was a poet and supported other artists. The "Poets' Parlour" at Knole became a place for writers to meet. He was very generous to poets like John Dryden. Other poets also visited Knole. The Poets' Parlour is now part of the Sackville-West family's private apartments.

Charles's son, Lionel Sackville, 1st Duke of Dorset, was born at Knole in January 1688. He inherited the estate when Charles died in 1706.

Knole Since 1700

Lionel Sackville strongly supported the new Hanoverian kings and was rewarded by King George I. He became the Duke of Dorset in 1720. In 1730, he was appointed lord lieutenant of Ireland. Later, in 1757, a crowd protested against a new law and attacked him in Knole Park, but he was saved by soldiers. He died peacefully at Knole House in 1765. His wife, Elizabeth, was a maid of honor to Queen Anne. Her good friend, Lady Elizabeth Germain, lived at Knole for so long that her rooms are still named after her today.

Lionel's son, Charles Sackville, 2nd Duke of Dorset, only lived four years after his father. But his grandson John Sackville, 3rd Duke of Dorset was very important for Knole. He loved collecting things and had the money to do it. He brought back many old master paintings from his travels in 1770. He also supported artists of his time. Sir Joshua Reynolds painted a full-length portrait of him, and the Duke bought several other paintings by Reynolds. Eleven of these are still in the Reynolds Room at Knole.

John Frederick's only son, George Sackville, 4th Duke of Dorset, died young in 1815. Knole was then left by the third Duke's widow in 1825 to their daughter Mary, Countess of Plymouth. She died without children in 1864, leaving it to her sister Elizabeth Sackville-West, Countess De La Warr and her male heirs. It eventually went to her fourth son, Mortimer Sackville-West, 1st Baron Sackville, and then to his family. However, Lord Sackville did not have enough money to keep up the house and its treasures. He started selling some of the family heirlooms to maintain the estate.

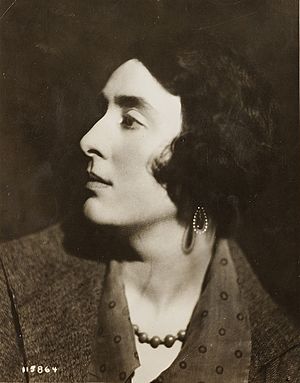

The Sackville-West family includes the famous writer Vita Sackville-West. Her book, Knole and the Sackvilles, published in 1922, is a classic about English country houses. It's written in a romantic style and sometimes has historical inaccuracies. But it was based on her full access to the old papers and books at the house.

In December 1922, Vita met Virginia Woolf, who became a friend and, for a while, her lover. Woolf wrote Orlando in 1927–1928. This experimental novel was inspired by Knole's history and Vita's ancestors, especially as told in Vita's book. The Sackville family tradition meant that Vita could not inherit Knole when her father, Lionel Sackville-West, 3rd Baron Sackville, died in 1928, because only male heirs could inherit. Woolf's novel gave Vita a magical version of Knole. When Vita read it, she wrote to Virginia, "You made me cry with your passages about Knole, you wretch." The original manuscript of Orlando is kept at Knole.

Art and Architecture at Knole

The House's Design

Knole has a long and complex history of building. But it is most important for its 17th-century design. As A. P. Newton said, Knole "looks almost exactly now as it did in the year Thomas Sackville died." It has stayed "motionless" since the early 1600s.

When Thomas Sackville rebuilt parts of Knole, his work wasn't considered very modern. In 1673, John Evelyn called it "a great old fashioned house." It didn't look like the popular classical style of the time. Knole might not look much like Archbishop Bourchier's medieval house anymore. But it still feels like a serious, strong group of buildings, partly because it's made of dark Kentish ragstone. However, Edward Town says it's important because Sackville "remarkably combined what was inherited from the existing building and what was newly built." He took a large, late-medieval house that had been used by powerful archbishops and changed it into a Jacobean country house. Sackville may have hired a skilled surveyor named John Thorpe for his building projects.

Beyond the 17th-century front, there's still a lot of evidence of the older house. One main part that remains is the northern section of Stone Court. The upper floors have fancy apartments. You can see this from features like the large toilet towers on the north side. The cellars below also have some wall paintings from the late 1400s.

In 2013, Knole received £7.75 million from the Heritage Lottery Fund for conservation and repair work. As part of this work, in 2014, archaeologists found scorched and carved marks on the old wooden walls, roof timbers, and floor beams, especially near fireplaces. News reports first said these were "witch marks" to stop witches and demons from coming down the chimney. This is one possible idea for these marks, which are now being found more often in medieval buildings across England. All ideas suggest they were meant to protect against fire or evil spirits. Since many of these marks are from the late Middle Ages and were covered up in the early 1600s, it's unlikely they were linked to King James I's interest in witchcraft. He actually became more doubtful about witches later on.

Rooms and Collections

Many of Knole's grand rooms are open to the public. They hold a collection of 17th-century royal Stuart furniture. These items were given to the 6th Earl because of his work for King William III in the royal court. The collection includes three state beds and rare silver furniture, like torch holders, a mirror, and a dressing table. There are also amazing tapestries and fabrics, and the famous Knole Settee.

The art collection has portraits by famous artists like Anthony van Dyck, Thomas Gainsborough, Sir Peter Lely, Sir Godfrey Kneller, and Sir Joshua Reynolds. Reynolds was a personal friend of the 3rd Duke. His portraits at Knole include a self-portrait and paintings of important figures like Samuel Johnson and Oliver Goldsmith. There's also a portrait of Wang-y-tong, a Chinese page boy who lived with the Sackville family.

You can also see items from the English Renaissance, like a delicate Italian-style staircase and a beautifully carved fireplace in the Great Chamber. The "Sackville leopards," which hold shields and are on the main staircase (built 1605–1608), come from the Sackville family's coat of arms. The chapel room and its crypt seem older than this period and have original pews.

The organ in Knole's private chapel is possibly the oldest playable organ in England. It has four sets of oak pipes and the keyboard is at the top. Its exact age isn't known, but an old guidebook mentioned a date of 1623, suggesting it was built around the 1620s. The organ's pitch is high, and its foot-pumped bellows still work.

The National Trust has a digital record of most of Knole's collection. It includes very important collections, especially of 17th-century state furniture.

Knole's Ownership and Use

The National Trust takes care of Knole and opens it to the public. The Trust has owned the house since Charles Sackville-West, 4th Baron Sackville donated it in 1947. However, the Trust only owns the house and a small part of the park (about 52 acres). The Sackville family or their family trust still live in much of the house and own the rest of the deer park. They allow public access and some charity and sports events.

There's a common story that Knole is a "calendar house," meaning it has 365 rooms, 52 staircases, 12 entrances, and seven courtyards. While the number of rooms is roughly correct, the number of staircases has changed over time. Traditionally, there are seven main courtyards: Green Court, Stable Court, Stone Court, Water Court, Queen's Court, Pheasant Court, and Men's Court. This list is a bit flexible, as there are other smaller courtyards too.

In January 2012, the National Trust started a seven-year plan to protect and restore the house. They asked the public for £2.7 million to help with this work.

Knole's Gardens

Knole has a 26-acre walled garden (30 acres if you include the house's area). It has a unique feature from medieval times: a smaller walled garden inside the larger one. It also has many other old garden features that are no longer common in country house gardens. These include clear views, pathways that spread out like a goose's foot, two long avenues, and shaped hedges. The herb garden near the orangery was designed in 1963 by Margaret Brownlow.

Knole Park

The house is set within its 1,000-acre deer park. This park has generally been kept in its traditional condition. However, the deer population is controlled and doesn't have access to all areas. Because of its rich woodland, Knole Park is a Site of Special Scientific Interest, meaning it's important for its natural features. The park also hosts the annual Knole Run, a cross-country race for schools.

Knole in Movies and Music

Knole was used for filming in January 1967 for the Beatles' music videos for Penny Lane and Strawberry Fields Forever. The stone archway where the Beatles rode horses can still be seen on the southeastern side of the Bird House, which is near Knole House. The same visit to Knole Park also inspired another Beatles song, Being for the Benefit of Mr. Kite!. John Lennon wrote it after buying an old poster in a nearby antique shop that advertised a circus.

Knole also appears in the 2008 film The Other Boleyn Girl, along with nearby Penshurst Place and Dover Castle. It has been featured in several other films, including Burke and Hare (2010), Sherlock Holmes: A Game of Shadows, and Pirates of the Caribbean: On Stranger Tides.

The British Film Institute has a free home video from 1961 that shows what the park looked like then. A 1950 film made by a local amateur group, the Sevenoaks Ciné Society, features the house in Hikers' Haunt. In May 2025, Knole was shown on the BBC's Hidden Treasures of the National Trust.

See also

- John Frederick Sackville, 3rd Duke of Dorset

- Lionel Bertrand Sackville-West, 6th Baron Sackville

| George Robert Carruthers |

| Patricia Bath |

| Jan Ernst Matzeliger |

| Alexander Miles |