Luigi Galleani facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Luigi Galleani

|

|

|---|---|

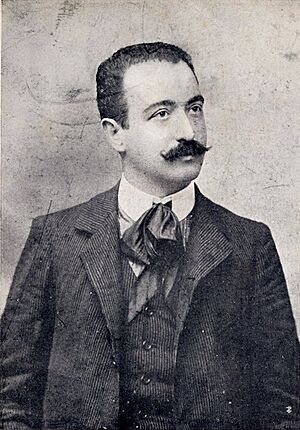

1919 police photograph of Galleani

|

|

| Born | 12 August 1861 |

| Died | 4 November 1931 (aged 70) Caprigliola, Aulla, Tuscany, Kingdom of Italy

|

|

Notable work

|

|

| Movement | Insurrectionary anarchism |

| Spouse(s) | Maria Galleani |

| Children | 4 |

Luigi Galleani (born August 12, 1861 – died November 4, 1931) was an Italian anarchist. He is best known for supporting "propaganda of the deed". This was a belief that political change could happen through violent actions and attacks.

Galleani was born in Vercelli, Italy. He became a key leader in the Piedmont labor movement. Because of his activism, he was sent away to the island of Pantelleria. In 1901, he escaped to the United States. He joined the Italian immigrant workers' movement in Paterson, New Jersey. Later, he moved to Vermont and Massachusetts. There, he started a radical newspaper called Cronaca Sovversiva.

Many Italian American anarchists became his loyal followers. They were known as the Galleanisti. This group carried out a series of bombing attacks across the United States.

During World War I, Galleani was part of the anti-war movement. Because of this, he was sent back to Italy. He faced harsh treatment there as fascism grew stronger. In his later years, he wrote The End of Anarchism?. This book defended anarchist communism against those who wanted slower changes. He believed in constant action against capitalism and the government. He also did not like formal organizations, seeing them as corrupt.

Contents

Luigi Galleani's Life Story

Early Years

Luigi Galleani was born on August 12, 1861. His family was middle-class and lived in Vercelli, Italy. He first learned about anarchism while studying law at the University of Turin. He later decided to give up his law career. Instead, he wanted to spread anarchist ideas against capitalism (a system where private businesses own most things) and the government.

He was a very good speaker and writer. This quickly made him an important voice in the new Italian anarchist movement. He worked with another anarchist, Pietro Gori. Together, they helped bring back strong anarchist activism. Many workers in Northern Italy began to follow them.

Working for Change

By the mid-1880s, anarchists were losing influence to the Italian Workers' Party (POI). This party had many supporters among northern workers. Galleani helped the anarchist movement work more closely with labor groups in Piedmont. In 1887, he started a newspaper called Gazzetta Operaia in Turin. He also created workers' groups in Vercelli. He shared revolutionary ideas with factory workers in Biella. In 1888, he gave many speeches across Piedmont. He also led workers' strike actions in Turin and Vercelli. This helped increase support for anarchists and the POI.

Galleani tried to get anarchists to join and influence the POI. He wanted to push the party towards revolutionary socialism. He tried to keep peace between those who wanted slow changes and those who wanted quick revolution. However, the two groups had very different ideas. Galleani's efforts to change the POI did not succeed.

In 1889, his radical actions put him at risk of arrest. He fled to France and then to Switzerland. There, he worked with a French anarchist, Élisée Reclus. He also helped organize a student protest at the University of Geneva. This protest honored the Haymarket martyrs. Galleani was arrested by Swiss police and sent back to Italy. He immediately continued his activism. He went on a speaking tour in Tuscany. He hoped to start an uprising on International Workers' Day in 1891.

In 1892, Galleani represented anarchists at the Genoa Workers' Congress. He wanted to stop the ideas of the main group, who wanted slow changes. Anarchists and worker groups, who both disliked political elections, formed an alliance. On August 14, a big argument happened between the anarchist and socialist groups. This led to them holding separate meetings. The socialists then formed the new Italian Socialist Party (PSI). Galleani and his friends tried to form an anarchist party, but they were not successful. This congress showed that Galleani's efforts had not gained wide support among workers. Many Italian anarchists became disappointed with the labor movement.

Life in Exile

After a period of unrest in Italy, the government began to crack down on anarchists. Many anarchists were arrested and sent away to small islands without a trial. Galleani was quickly arrested. He was found guilty of conspiracy and sent to the Sicilian island of Pantelleria. There, he met and married Maria Rallo, who already had a young son. Luigi and Maria Galleani had four children together.

With help from Elisee Reclus, Galleani escaped from Italy to Egypt. He stayed there with other Italian immigrants for a year. When he was threatened with being sent back to Italy, he fled to the United States. He arrived in October 1901, shortly after the assassination of President William McKinley.

Life in the United States

Galleani settled in Paterson, New Jersey. This city was a center for Italian immigrant silk workers. He became the editor of an Italian anarchist newspaper called La Questione Sociale. He strongly supported the 1902 Paterson silk strike. He gave speeches calling for a revolutionary general strike to end capitalism. When striking workers clashed with police, he was injured and charged with encouraging a riot. He escaped to Canada to recover. He then secretly returned to the US and hid in Barre, Vermont. He stayed with Italian stonemasons there.

With these new friends, he started Cronaca Sovversiva on June 6, 1903. This newspaper quickly became the most important Italian anarchist paper in North America. It was sent all over the world. Through this paper, in 1905, he published a manual called La Salute è in voi!. In it, he shared a formula for making explosives.

In 1906, another newspaper revealed Galleani's location. He was quickly found by the authorities. He was arrested and brought back to Paterson. He was tried for encouraging a riot, but the jury could not agree, so he was released. He returned to Barre. There, he continued giving powerful speeches and writing many articles for his newspaper. He quickly became a leading voice in the Italian American anarchist movement.

In late 1907, a socialist named Francesco Saverio Merlino publicly said he no longer believed in anarchism. He preferred slower changes through labor unions. In response, Galleani wrote a series of articles defending anarchism. By this time, he had become disappointed with the labor movement. He began to reject labor unions completely. He believed in a form of anarchism that did not have formal organizations. This idea became very popular among Italian American anarchists.

Galleani gained many strong and loyal followers, known as the Galleanisti. They also rejected all formal organization. They developed very strong beliefs. Famous followers included Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti. They helped promote Galleani's speeches and spread his writings. The Galleanisti formed small, close-knit groups of people who chose to join. Even though they rejected formal leaders, Galleani was highly respected, almost like an unofficial leader.

Deportation and Later Life

When the United States joined World War I, Galleani became a key leader in the anti-war movement. He declared that anarchists were "Against the War, Against the Peace, For Social Revolution!" When a law was passed requiring men to register for the military, he told his followers to refuse and hide. He and many friends moved to a cabin in the woods near Taunton, Massachusetts. Some Galleanisti went to Mexico. They planned to return to Italy, believing a revolution was about to happen there.

His anti-war actions made him a target for the American government. On June 17, 1917, federal agents raided the offices of Cronaca Sovversiva. They arrested Galleani and shut down the newspaper. He and eight of his followers were charged with conspiracy. They were sent back to Italy on June 24, 1919, leaving his family behind in the United States.

He tried to continue publishing Cronaca Sovversiva in Turin, Italy. However, the Italian authorities quickly stopped it. After the March on Rome in 1922, he was arrested. The new fascist government found him guilty of trying to cause rebellion. They sentenced him to 14 months in prison. After being released, he finished his arguments against Merlino. He wrote more articles and published them in his book The End of Anarchism? (1925).

This book was praised by another anarchist, Errico Malatesta. But in November 1926, it led to Galleani's arrest by the fascist authorities. He was accused of insulting the Italian dictator Benito Mussolini. Galleani was imprisoned for several months. Later, he was sent away to Lipari and then Messina, where he was jailed for 6 months.

In February 1930, he was allowed to leave prison because he was very sick. He went to live in Caprigliola, a small town near Carrara. He was watched closely by the police. One day, after a walk, he collapsed from a heart attack. He died on November 4, 1931.

Galleani's Ideas

Galleani's ideas about anarchist communism combined different thoughts. He mixed the idea of insurrectionary anarchism (quick, violent uprising) with mutual aid (people helping each other). He believed in revolutionary spontaneity (changes happening naturally and suddenly), autonomy (self-rule), diversity, self-determination (making your own choices), and direct action (taking action directly, not through representatives). He supported using violence to overthrow the government and capitalism. He called this "propaganda of the deed."

He did not believe in any formal organizations, like anarchist groups or labor unions. He thought they would always become corrupt. He believed that social change could only happen through violent attacks on institutions. He thought these attacks could lead to a popular uprising. He openly supported "propaganda of the deed." This included assassinating important figures and taking over private property. Galleani supported the assassination of President William McKinley and King Umberto I of Italy.

Galleani's main goal was to create "a society without masters, without government, without law, without any forced control." He wanted a society where people worked together by agreement. Everyone would have the freedom to make their own choices. He believed that once the government and capitalism were gone, people would naturally know how to live in a free and equal society.

Galleani's Impact

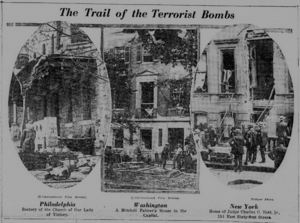

After Galleani was sent away from the United States, his followers, the Galleanisti, started a series of attacks. They carried out a series of bombings in 1919. In April 1919, the Galleanisti sent about thirty bombs to government officials. Most of these bombs were found and stopped before they could explode. Only one bomb went off, injuring a maid. In June 1919, they launched nine coordinated bombings across the Northeastern United States. However, none of their targets were killed or seriously hurt. One bomb exploded too early outside Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer's house, killing the attacker. Another bomb found in a church exploded after police discovered it, killing ten police officers and a bystander.

After these events, the government started a period of political repression. Many Galleanisti were arrested. This included Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti. They were executed even though there was not much evidence against them. In response, a Galleanist named Mario Buda was thought to have carried out the Wall Street bombing of 1920. This attack killed 33 people.

In the 1930s, an anarchist named Marcus Graham tried to restart the Galleanist movement. He started a newspaper called Man! in San Francisco. But his efforts were not successful, and the paper closed in 1939. By the end of World War II, the Italian American anarchist movement had mostly disappeared. The Galleanist newspaper L'Adunata dei Refrattari continued until 1971. It was then followed by another anti-government paper called Fifth Estate.

By the late 20th century, Luigi Galleani was largely forgotten. Not many scholars studied him. But in 1982, his book The End of Anarchism? was translated into English. This sparked new interest in his ideas. In 2006, more of his works were translated and published in a collection.

Selected Writings

- (1914) Contro la guerra, contro la pace, per la rivoluzione sociale; English translation: Against War, Against Peace, For The Social Revolution (1983, Centrolibri Books)

- (1925) La fine dell'Anarchismo?; English translation: The End of Anarchism? (1982, Cienfuegos Press)

- (1927) Il principio dell'organizzazione alla luce dell'anarchismo; English Translation: The Principal of Organization to the Light of Anarchism (2006, Pirate Press)

See also

- First Red Scare