Major Taylor facts for kids

Taylor in July 1907

|

|||

| Personal information | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Full name | Marshall Walter Taylor | ||

| Nickname | Worcester Whirlwind | ||

| Born | November 26, 1878 Indianapolis, Indiana, U.S. |

||

| Died | June 21, 1932 (aged 53) Chicago, Illinois, U.S. |

||

| Team information | |||

| Discipline | Track | ||

| Role | Rider | ||

| Rider type | Sprinter | ||

| Major wins | |||

|

|||

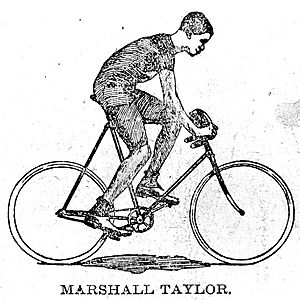

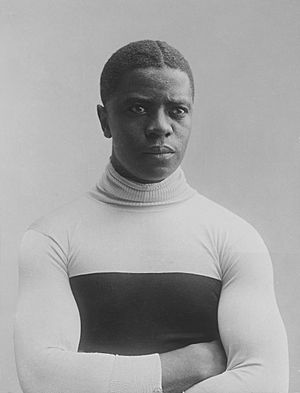

Marshall Walter "Major" Taylor (born November 26, 1878 – died June 21, 1932) was an African-American professional cyclist. Many people consider him one of the greatest American sprinters of all time.

He grew up in Indianapolis, where he worked in bike shops. He started racing in both track and road events. As a teenager, he moved to Worcester, Massachusetts, with his boss and coach. There, he continued his successful amateur career, even breaking track records.

Taylor became a professional cyclist in 1896, when he was 18. He lived in cities along the East Coast and took part in many track events. In 1897, he focused on sprint races. He won many events and became very popular. In 1898 and 1899, he set many world records for distances from a quarter-mile (0.4 km) to two miles (3.2 km).

In 1899, Taylor won the 1-mile sprint event at the world championships. This made him the first African American to become a cycling world champion. He was also the second black athlete to win a world championship in any sport. Taylor was a national sprint champion in 1899 and 1900. From 1901 to 1904, he raced in the U.S., Europe, and Australasia, beating the world's best riders. After a break, he returned to racing from 1907 to 1909. He retired at age 32 in 1910.

Later in his life, Taylor faced money problems. He spent his last two years in Chicago, Illinois, where he died in 1932. Throughout his career, he fought against the racial prejudice he met on and off the track. He became an important role model for other athletes facing discrimination. Many cycling clubs, trails, and events in the U.S. are named after him. These include the Major Taylor Velodrome in Indianapolis and Major Taylor Boulevard in Worcester. There are also memorials and historic markers in his honor. His story has been shared in films, music, and fashion.

Contents

Early Life and First Rides

Marshall Walter Taylor was born on November 26, 1878, in Indianapolis, Indiana. His father, Gilbert Taylor, was a Civil War veteran. His parents moved from Louisville, Kentucky, to a farm near Indianapolis. Marshall was one of eight children. Around 1887, his father started working as a coachman for a wealthy white family named Southard in Indianapolis.

When Marshall was a child, he sometimes went to work with his father. He became good friends with the Southards' son, Daniel. From about age 8 to 12, Marshall lived with the Southard family and was tutored at their home. This gave him more chances than his own parents could offer. But this time ended when the Southards moved to Chicago, Illinois. Marshall stayed in Indianapolis and moved back home with his parents.

The Southards gave Marshall his first bicycle. By 1891 or 1892, he was so good at bike tricks that a bike shop owner, Tom Hay, hired him. Marshall performed stunts outside the Hay and Willits bicycle shop. He earned $6 a week for cleaning the shop and doing stunts. He also got a free bicycle. People think he got his nickname "Major" because he wore a military uniform while doing his stunts.

In 1892 or 1893, Taylor started a new job at Harry T. Hearsey's bicycle shop. He taught people how to ride bikes. While working there, Taylor met Louis D. "Birdie" Munger. Munger owned a racing bicycle factory in Indianapolis. Munger was a former high-wheel bicycle racer. They became friends, and Munger hired Taylor to do odd jobs. Taylor would go to high schools and colleges to train cyclists and promote Munger's racing bikes. Munger also decided to help Taylor become a champion racer.

Becoming an Amateur Racer

Taylor raced in both road and track races as an amateur. But he was best at track sprints, especially the 1-mile (1.6 km) race. Taylor won his first bike race in 1890. It was a 10-mile (16 km) amateur event in Indianapolis. He got a 15-minute head start because he was so young. He later finished third in a race in Peoria, Illinois, for riders under 16.

Taylor faced racial prejudice throughout his racing career. Some track owners would not let him compete because they feared other cyclists would refuse to race. For example, in 1893, when Taylor was 15, he broke a one-mile amateur track record. But he was booed and then banned from the track. Taylor joined the See-Saw Cycling Club. This club was formed by black cyclists in Indianapolis who could not join the all-white Zig-Zag Cycling Club.

Major Taylor won his first big race on June 30, 1895. He was the only rider to finish a tough 75-mile (121 km) road race near Indianapolis. During the race, white competitors threatened him. A few days later, on July 4, 1895, Taylor won a 10-mile road race in Indianapolis. This win allowed him to race at the national championships for black racers in Chicago. He won that 10-mile championship race and set a new record for black cyclists.

In 1895, Taylor and Munger moved from Indianapolis to Worcester, Massachusetts. Worcester was a major center for the U.S. bicycle industry. Munger, who was Taylor's boss and friend, moved his bike business there. Massachusetts was also a more tolerant place.

Munger and his business partner started the Worcester Cycle Manufacturing Company. Taylor continued to work for Munger as a bicycle mechanic and messenger. Moving to the East Coast gave Taylor more chances to be seen. It also meant bigger crowds, more sponsors, and access to better cycling tracks. After moving, Taylor joined the all-black Albion Cycling Club in 1895. He also trained at the YMCA in Worcester.

In 1896, Taylor entered many races in the Northeastern states. After winning a 10-mile road race in Worcester, he competed in a 25-mile (40 km) race in New Jersey. Someone threw ice water in his face near the finish line, and he ended up in 23rd place. Taylor's first major East Coast race was a League of American Wheelmen (LAW) one-mile race. He started last but won the event. In August 1896, Taylor set an unofficial new track record in Indianapolis. His final amateur race was on November 26, 1896, in New York.

Professional Cycling Career

First Professional Races (1896)

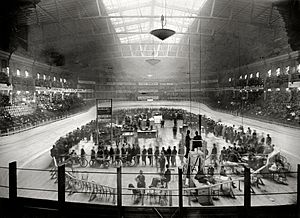

Taylor became a professional cyclist in 1896, at age 18. He quickly became "the most formidable racer in America." His first professional race was on December 5, 1896, in front of 5,000 people. It was a half-mile handicap race on an indoor track at New York City's Madison Square Garden II. Taylor started with a 35-yard (32 m) lead. He won the race, beating other top riders.

From December 6–12, 1896, Taylor took part in a six-day race at Madison Square Garden. This was the longest race Taylor had ever entered. These long, tough races were very popular. Riders often suffered from exhaustion and lack of sleep. Taylor refused to keep racing on the final day because he was so tired. He completed 1,732 miles (2,787 km) in 142 hours, finishing in eighth place. He never competed in such a long race again.

After becoming a professional, Taylor lived in Worcester and Middletown, where Munger had bike factories. He also lived in other eastern cities like South Brooklyn.

Rising to Fame and Setting Records (1897–1898)

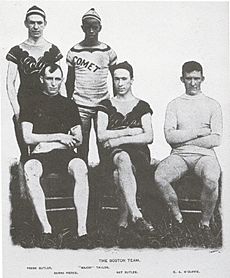

Taylor first raced for Munger's Worcester Cycle Manufacturing Company. When the company faced problems in 1897, he joined other racing teams. In 1897, Taylor competed in his first full year as a professional. He won many races, including a one-mile race in Boston and a quarter-mile (0.4 km) race in Brooklyn.

As a black cyclist, Taylor continued to face racial prejudice. In late 1897, when races moved to the racially-segregated South, local organizers would not let him compete. Taylor returned to Massachusetts for the rest of the season. Despite these challenges, Taylor was determined to race.

In his early professional years, Taylor's fame grew as he won more races. Newspapers called him the "Worcester Whirlwind," the "Black Cyclone," and the "Ebony Flyer." He became very popular with fans. Even President Theodore Roosevelt followed Taylor's career.

In 1898, Taylor won big victories in Philadelphia. He took first place in the one-mile championship. On August 27, he set a new world record of 1:41 2/5 for a one-mile paced race. He beat Welsh racer Jimmy Michael.

Taylor was one of several top cyclists who could claim the national championship in 1898. However, new cycling leagues made the title unclear. Taylor, a devoted Baptist, refused to race in the finals of a championship because they were held on a Sunday. As a result, he was suspended from one league. He later rejoined another.

Between 1898 and 1899, at the peak of his career, Taylor set seven world records. These included distances from a quarter-mile to two miles. His one-mile world record of 1:41 from a standing start lasted for 28 years.

World Sprint Champion (1899)

At the 1899 world championships in Montreal, Canada, Taylor won the one-mile sprint. This made him the first African American to win a world championship in cycling. He was the second black athlete ever to win a world championship in any sport. For many years, he was the only black cycling world champion. Taylor won the one-mile world championship sprint closely, just ahead of a French and an American rider. He also placed second in the two-mile championship sprint. Because the finals were on Sundays, Taylor refused to compete for religious reasons. He did not race in another world championship until 1909.

After Taylor's world championship win, some people said the event was not fair. They claimed Taylor had not raced against the strongest riders. This was because the world cycling group did not allow some racers to compete. So, Taylor's achievements were sometimes downplayed.

In 1899, Taylor won 22 first-place finishes in major races across the U.S. His record-breaking times were amazing. No other rider had won so many different types of races. This made him famous around the world. In November 1899, Taylor set a new world record of 1:19 for the one-mile paced distance. This made him "the fastest man in the world" again.

For the 1899 racing season, Taylor signed a contract to race for the E. C. Stearns Company. Stearns built special bicycles for Taylor. These bikes were very light and had unique gears. Stearns also built a special steam-powered pacing tandem bike. This helped Taylor break Eddie McDuffie's one-mile world record on November 15, 1899. He set a time of 1:19, reaching a speed of 45.56 mph (73.32 km/h). Later in 1899, Taylor signed a contract to race for the Iver Johnson's Arms & Cycle Works team in 1900.

American Sprint Champion (1900)

In 1900, Taylor's future as a professional racer was uncertain. But the racing groups that had banned him let him back in after he paid a fine. Taylor won the American sprint championship in 1900. He also beat Tom Cooper, the 1899 champion, in a one-mile race at Madison Square Garden. Between 50,000 and 60,000 people watched this race. Taylor also set world records in the half-mile and two-thirds-mile sprints. He even performed as a vaudeville act, racing indoors against other riders. Taylor eventually bought a home in Worcester in 1900.

Racing in Europe and Australasia (1901–1904)

After his success in the U.S. and Canada, Taylor went on a European tour in 1901. He still refused to race on Sundays because of his religious beliefs. Most finals were held on Sundays. Taylor always carried a Bible and said a silent prayer before each race.

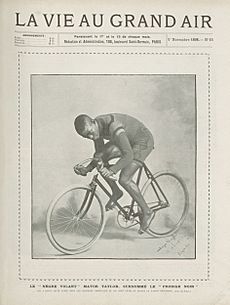

Taylor was very popular with European fans and reporters. "Everywhere he went he was mobbed, talked about, or written up." In 1901, Taylor won 18 of the 24 European races he entered. He had 42 victories if you count individual heats. A highlight was his two races against French champion Edmond Jacquelin in Paris. Taylor won the second match.

Taylor also toured Europe in 1902. He entered 57 races and won 40 of them. He beat champions from Germany, England, and France. In 1903 and 1904, Taylor also raced in Australia and New Zealand. He earned a lot of prize money during his world tour in 1903, estimated at $35,000.

Later Years and Retirement (1907–1910)

Taylor took a two-and-a-half-year break from cycling between 1904 and 1906. He was tired from the mental and physical stress of racing. He returned to race in France in 1907. He set two world records in Paris for the half-mile and quarter-mile standing starts. Taylor also raced in Europe in 1908 and 1909. In 1909, he finally raced on a Sunday, near the end of his career. Taylor's last professional race was on October 10, 1909, in France. He won the race and retired from competitive cycling in 1910.

Taylor was still breaking records in 1908, but his age was catching up. He retired from racing in 1910 at age 32. When he returned to his home in Worcester, his net worth was estimated to be between $75,000 and $100,000. Taylor won his final competition, an "old-timers race" for former professional racers, in New Jersey in September 1917.

Facing Racism in Cycling

As Taylor became famous, he still faced racial segregation. In 1894, the LAW changed its rules to keep black people from becoming members. However, they still allowed them to compete in races. Taylor's cycling was celebrated in other countries, especially France. But his career was limited by racism, especially in the Southern U.S. Some local organizers would not let him race against white cyclists. Some restaurants and hotels also refused to serve him or let him stay.

In his autobiography, Taylor said that other famous cyclists often worked together to try and beat him. He said they would bump, jostle, and elbow him to stop him from sprinting ahead. His manager, William A. Brady, even criticized other riders for their "rough treatment" of Taylor.

Some of Taylor's competitors refused to race with him. Others tried to scare him or hurt him. While racing in Savannah, Georgia in 1898, he received a written threat. Taylor remembered that ice water was thrown at him during races. Nails were also scattered in front of his wheels. He said other riders would "pocket" him (box him in) to stop him from using his successful sprinting tactic.

Taylor's competitors also tried to injure him. In 1897, after a race in Taunton, Massachusetts, a rider named William Becker tackled Taylor and choked him until he passed out. Becker claimed Taylor had crowded him. Becker was suspended and fined $50. In 1904, while Taylor was racing in Australia, another rider, Iver Lawson, crashed into his front wheel. Taylor fell and was unconscious. He was taken to a hospital but recovered fully. Lawson was banned from racing for a year.

Life is too short for any man to hold bitterness in his heart and that is why I have no feeling against anybody.

Taylor explained that he shared these stories in his autobiography to inspire other African American athletes. He wanted to show them how to overcome racial prejudice in sports. Taylor said that the exhaustion and stress from racism made him retire from cycling in 1910. He advised young African Americans to live cleanly, play fairly, and be good sports. He told them to develop their talents with strong character, willpower, and courage. Despite many challenges, Taylor became one of the best athletes of his time.

Retirement and Later Life

After retiring from racing, Taylor tried to study engineering. But he was not accepted because he did not have a high school diploma. He then started various businesses.

About 20 years after he retired, Taylor wrote and published his autobiography. It was called The Fastest Bicycle Rider in the World (1928). In his book, Taylor seemed positive about his retirement. He felt he had a "wonderful day." He also said he had no regrets or "animosity toward any man." But he did hint at some bitterness about how he was treated. He wrote that he always played fairly, even when he was not given a fair chance.

By 1930, Taylor faced serious money problems. He made bad investments, and the stock market crash hurt him. His businesses were not successful. He had to sell his home in Worcester and some family belongings to pay off debts. He also had ongoing health issues.

Not much is known about Taylor's life after his marriage ended and he moved to Chicago around 1930. Taylor spent his last two years living in poverty. He sold copies of his autobiography to earn a small income. He lived at the YMCA Hotel in Chicago.

In March 1932, Taylor had a heart attack and was hospitalized. After an unsuccessful heart operation, he died on June 21, at age 53. His wife and daughter did not immediately know of his death. No one claimed his body. He was first buried in an unmarked pauper's grave. In 1948, a group of former cyclists used money from Frank W. Schwinn (owner of the Schwinn Bicycle Co.) to rebury Taylor's remains in a more noticeable spot. The plaque at his grave honors him as a "World's champion bicycle racer who came up the hard way without hatred in his heart, an honest, courageous and God-fearing, clean-living gentlemanly athlete. A credit to his race who always gave out his best. Gone but not forgotten."

Major Taylor's Legacy

Taylor's legacy is his courage in challenging racial prejudice as an African American athlete. He was a sports hero in France and Australia. Taylor became a role model for other athletes facing discrimination. He was "the first great black celebrity athlete" and helped pave the way for others. Taylor wrote in his autobiography that he had no other African Americans to give him advice. He "therefore had to blaze my own trail."

Honors and Tributes

Taylor's story was not widely known until 1982. That year, the Major Taylor Velodrome opened in Indianapolis for the U.S. Olympic Festival. Annual events named after Taylor take place there. In 1989, Taylor was added to the U.S. Bicycling Hall of Fame. He also received other awards in the 1990s. In 2002, he was one of nine track cyclists inducted into the UCI Hall of Fame. In 2003, he was named a Sports Ethics Fellow. In 2009, a state historical marker was placed in Indianapolis to honor him. In 2018, he received a special tribute at the Jesse Owens Awards.

In 1998, in Worcester, where Taylor lived for 35 years, the Major Taylor Association was formed. Their goal was to build a memorial for him. On July 24, 2006, a busy street in downtown Worcester was renamed Major Taylor Boulevard. A bronze sculpture of Taylor was unveiled on May 21, 2008. It was created by Antonio Tobias Mendez. In 2002, a teaching guide about Taylor was developed for schools. Since 2003, Worcester has hosted an annual bike race called the "George Street Bike Challenge for Major Taylor."

The first cycling club named after Taylor was formed in Columbus, Ohio, in 1979. In 2008, many of these clubs joined to form the National Brotherhood of Cyclists (NBC). This group works to make cycling more diverse. The Major Taylor Trail, a 6-mile (9.7 km) rail trail in Chicago, opened in 2007. A large mural honoring Taylor was created along the trail in 2018. The Major Taylor Project, a youth cycling program, was launched in Washington state in 2009.

A small museum about Taylor opened in 2021 in Worcester. Taylor's great-granddaughter attended the opening.

In Popular Culture

Actor Philip Morris played Taylor in the 1992 TV mini-series Tracks of Glory. Blues musician Otis Taylor (no relation) wrote a song about him called "He Never Raced on Sunday" in 2004. In 2007, Nike released a special collection of sneakers inspired by Major Taylor. SOMA Fabrications also started making a type of bicycle handlebar named after him. Dewshane Williams played Taylor in a 2013 episode of the TV show Murdoch Mysteries.

In 2018, the cognac brand Hennessy announced that Taylor would be part of their "Wild Rabbit" advertising campaign. This campaign tells inspiring stories of influential people. It included a bronze sculpture of Taylor by Kadir Nelson. A TV commercial featuring Taylor, narrated by rapper Nas, was shown during the 2018 NBA Finals. A shorter version was shown during the Super Bowl LIII in 2019. ESPN also showed a Hennessy-sponsored documentary about Taylor called The Six Day Race.

In 2019, two Taylor-inspired products were released. Fashion designer Kerby Jean-Raymond created a clothing collection. Affinity Cycles made special replica track bicycles. Part of the money from these sales went to the NBC. Bicycle rides were held across the U.S. to honor Taylor's birthday. A $25,000 scholarship was also created in his name.

Graphic novel publisher Drawn and Quarterly plans to publish a graphic novel biography of Taylor in 2023.

Family Life

Taylor married Daisy Victoria Morris on March 21, 1902. She was born in Hudson, New York, in 1876. Taylor met her around 1900 when she lived in Worcester with her aunt and uncle.

In 1904, while in Australia, Taylor and his wife had their only child. They named their daughter Rita Sydney, after Sydney, Australia, where she was born on May 11. When Taylor, his wife, and daughter were not traveling, they lived in a large home in Worcester that Taylor bought in 1900.

After Taylor retired from racing in 1910, his businesses did not do well in the 1920s. He and his wife became separated. She left him in 1930 and moved to New York City. Around the same time, Taylor moved to Chicago. He never saw his wife or daughter again.

Taylor's daughter graduated from college and taught physical education. She passed away in 2005 at age 101. She had a son, Dallas C. Brown Jr., and five grandchildren. In 1984, Taylor's daughter gave a large collection of scrapbooks about her father to the University of Pittsburgh Archives.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Marshall Major Taylor para niños

In Spanish: Marshall Major Taylor para niños

| Chris Smalls |

| Fred Hampton |

| Ralph Abernathy |