Diamondback terrapin facts for kids

The diamondback terrapin or simply terrapin (Malaclemys terrapin) is a type of turtle that lives in the salty coastal marshes of the eastern and southern United States, and in Bermuda. It's the only species in its group, Malaclemys. This turtle has one of the widest living areas of all North American turtles, found from the Florida Keys in the south all the way up to Cape Cod in the north.

The name "terrapin" comes from an old Algonquian word, torope. Early European settlers in North America used this name for these turtles that lived in salty water, not in fresh water or the open sea. In American English, it still mostly means this specific turtle. However, in British English, other water turtles like the red-eared slider might also be called terrapins.

Quick facts for kids Diamondback terrapin |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Photographed in the wild | |

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification |

|

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | Testudines |

| Suborder: | Cryptodira |

| Family: | Emydidae |

| Genus: | Malaclemys Gray, 1844 |

| Species: |

M. terrapin

|

| Binomial name | |

| Malaclemys terrapin (Schoepff, 1793)

|

|

| Script error: The function "autoWithCaption" does not exist. | |

Script error: No such module "Check for conflicting parameters".

Contents

What Diamondback Terrapins Look Like

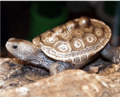

The name "diamondback" comes from the cool diamond-like pattern on their top shell, called the carapace. But their colors and patterns can be very different! Their shell is usually wider at the back, looking a bit like a wedge from above.

Shell colors can range from brown to gray. Their bodies can be gray, brown, yellow, or even white. Each terrapin has unique black wavy marks or spots on its body and head. They also have large, webbed feet, which help them swim.

Male and female terrapins are different sizes. Males grow to about 13 cm (5 inches) long. Females are much bigger, averaging around 19 cm (7.5 inches) long. The biggest female ever found was over 23 cm (9 inches) long! Terrapins from warmer places tend to be larger. Males weigh about 300 grams (10.5 ounces), while females weigh around 500 grams (17.6 ounces). The largest females can weigh up to 1000 grams (2.2 pounds).

How Terrapins Survive in Their Environment

Terrapins look a lot like their freshwater relatives. However, they are very well-suited to living near the coast in salty water. They have special ways to handle different salt levels. They can live in full-strength saltwater for a long time. Their skin doesn't let much salt in.

Terrapins have special salt glands near their eyes. These glands help them get rid of extra salt, especially when they are thirsty. They can even tell the difference between salty and fresh drinking water. They have clever ways to find fresh water, like drinking the freshwater layer that floats on top of saltwater after rain. They also raise their heads to catch raindrops.

These turtles are strong swimmers. They have very webbed back feet, but not flippers like sea turtles. Like their relatives, they have strong jaws. These jaws are perfect for crushing the shells of their prey, like clams and snails. Female terrapins have even bigger and stronger jaws than males.

Types of Diamondback Terrapins

Scientists recognize seven different types, or subspecies, of diamondback terrapins. They are:

- M. t. centrata (Latreille, 1801) – Carolina diamondback terrapin (found in Georgia, Florida, North Carolina, South Carolina)

- M. t. littoralis (Hay, 1904) – Texas diamondback terrapin (found in Texas)

- M. t. macrospilota (Hay, 1904) – Ornate diamondback terrapin (found in Florida)

- M. t. pileata (Wied, 1865) – Mississippi diamondback terrapin (found in Alabama, Florida, Louisiana, Mississippi, Texas)

- M. t. rhizophorarum (Fowler, 1906) – Mangrove diamondback terrapin (found in Florida)

- M. t. tequesta (Schwartz, 1955) – East Florida diamondback terrapin (found in Florida)

- M. t. terrapin (Schoepff, 1793) – Northern diamondback terrapin (found in Connecticut, Delaware, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Jersey, New York, North Carolina, Rhode Island, Virginia)

There's also a group of terrapins in Bermuda. They got there on their own, not by humans. Scientists haven't officially named them a subspecies yet. But their DNA shows they are closely related to the terrapins from the Carolinas.

Where Terrapins Live

Diamondback terrapins live in a thin strip of coastal areas along the Atlantic and Gulf Coasts of the United States. Their range stretches from Cape Cod, Massachusetts, down to the southern tip of Florida. It then goes around the Gulf Coast to Texas.

In most places, terrapins live in Spartina marshes. These marshes get covered by water during high tide. In Florida, they also live in mangrove swamps. These turtles can live in both fresh water and full-strength ocean water. However, adult terrapins prefer water that's a mix of fresh and salt.

No other turtles compete with them in these salty areas. Even though common snapping turtles sometimes use salty marshes, terrapins are unique. Scientists aren't sure why terrapins don't live in the upper parts of rivers in their range. They can handle fresh water in captivity. It might be because of where their food is found.

Terrapins stay quite close to shore. They don't wander far out to sea like sea turtles do. The terrapins in Bermuda settled there naturally. Terrapins usually stay in the same areas for most of their lives. They don't travel long distances.

The Terrapin Life Cycle

Adult diamondback terrapins mate in early spring. Females lay clutches of 4 to 22 eggs in sand dunes during early summer. The eggs hatch in late summer or early fall.

Male terrapins become adults in 2–3 years, when they are about 11.4 cm (4.5 inches) long. Females take longer, about 6–7 years (or 8–10 years for northern terrapins). They are about 17 cm (6.75 inches) long when they mature.

How Terrapins Reproduce

Like all reptiles, terrapin eggs are fertilized inside the female. Mating has been seen in May and June. It's similar to how the closely related red-eared slider mates. Female terrapins can mate with several males. They can also store sperm for years. This means some clutches of eggs can have more than one father.

Like many turtles, the sex of terrapin hatchlings depends on the temperature of the nest. This is called temperature-dependent sex determination. Females can lay up to three clutches of eggs per year in the wild. In captivity, they can lay up to five clutches a year. We don't know how often they might skip laying eggs.

Females might travel far on land before they nest. Nests are usually laid in sand dunes or bushy areas near the ocean. This happens in June and July. But in Florida, nesting can start as early as late April. Females will quickly leave a nest if they are disturbed while laying eggs.

The number of eggs in a clutch changes depending on the location. In southern Florida, the average is 5.8 eggs per clutch. In New York, it's 10.9 eggs. After covering the nest, terrapins quickly go back to the ocean. They only return to nest again.

The eggs usually hatch in 60–85 days. This depends on the temperature and how deep the nest is. Hatchlings usually come out of the nest in August and September. But sometimes, they hatch and stay in the nest through the winter. Hatchlings sometimes stay on land in the nesting areas in both fall and spring. They might even stay on land for most or all of the winter in some places. Young terrapins can survive freezing temperatures. This helps them stay on land during winter. Young terrapins have less salt tolerance than adults. Studies show that one- and two-year-old terrapins use different habitats than older ones.

How fast they grow, when they become adults, and how long they live are not well known for wild terrapins. Males become sexually mature before females because they are smaller. For females, becoming an adult depends on their size, not their age. Estimating their age by counting growth rings on their shell hasn't been fully tested yet. So, it's hard to know the exact age of wild terrapins.

What Terrapins Do Seasonally

Nesting is the only time terrapins are on land. So, we don't know much about their other behaviors. Limited information suggests that terrapins hibernate during the colder months in most of their range. They do this by burying themselves in the mud of creeks and marshes.

What Diamondback Terrapins Eat

Diamondback terrapins typically eat fish, crustaceans like shrimp and crabs. They also eat marine worms, marine snails (especially the saltmarsh periwinkle), clams, barnacles, mussels, other mollusks, insects, and dead animals. Sometimes, they eat small amounts of plants, like algae.

If there are many terrapins in one area, they can eat so many invertebrates that it affects the ecosystem. This is partly because periwinkles themselves can eat too much of important marsh plants, like cordgrass. What a terrapin eats can depend a lot on its gender and age. Males and young females tend to eat fewer different types of food. Adult females have powerful jaws. They sometimes eat crustaceans like crabs and are more likely to eat hard-shelled mollusks.

Protecting Diamondback Terrapins

Terrapin Status

In the 1900s, people thought terrapins were a delicious food. They were hunted so much that they almost disappeared. Their numbers also dropped because coastal areas were developed. Terrapins were also hurt by boat propellers. Another common cause of death is getting caught in crab traps. The turtles are attracted to the same bait as the crabs.

Because of these problems, the diamondback terrapin is now listed as an endangered species in Rhode Island. It's a threatened species in Massachusetts. It's considered a "species of concern" in Georgia, Delaware, Alabama, Louisiana, North Carolina, and Virginia. In New Jersey, it was recommended to be a Species of Special Concern in 2001. In July 2016, New Jersey stopped allowing hunting of this species. In Connecticut, there is no hunting season for them. However, the U.S. federal government does not have a special conservation status for them.

Conservation Efforts

The IUCN says the species is Near Threatened. This is because their numbers are going down in many places. Some states protect terrapins, but there isn't much national or international protection.

Diamondback terrapins are the only U.S. turtles that live in the salty waters of estuaries, tidal creeks, and salt marshes. They used to live from Massachusetts to Texas. But their populations have been greatly reduced by human development and other impacts along the Atlantic coast.

The Earthwatch Institute helps with a research program called "Tagging the Terrapins of the Jersey Shore." Volunteers help scientists find these turtles in New Jersey's Barnegat Bay. This helps them learn how to protect terrapins as human development grows.

Dangers to Terrapins

The biggest dangers to diamondback terrapins come from humans. These dangers are different in various parts of their range. People often build cities on ocean coasts near large rivers. When they do this, they destroy many of the huge marshes where terrapins live. Across the country, probably more than 75% of the salt marshes where terrapins lived have been destroyed or changed. Now, rising ocean levels threaten the remaining marshes.

Crab traps, used by both businesses and individuals, often catch and drown many diamondback terrapins. This can lead to more males than females in populations. It can also cause local population drops, or even make terrapins disappear from an area. When these traps are lost, they can keep killing terrapins for many years. Special devices are available to add to crab traps. These devices stop terrapins from getting trapped, but they don't stop crabs from being caught. In some states, these devices are required by law.

Nests, hatchlings, and sometimes adult terrapins are often eaten by raccoons, foxes, rats, and many types of birds, like crows and gulls. There are often more of these predators in areas where humans live. Predator attacks can be very high. For example, raccoons ate 92-100% of terrapin nests each year from 1998–2008 at Jamaica Bay Wildlife Refuge in New York.

Terrapins are also killed by cars when nesting females cross roads. Many terrapins can die this way, which can seriously harm their populations. In some states, terrapins are still caught for food. Pollutants like metals and chemicals might affect terrapins, but this hasn't been clearly shown in wild populations.

There's also a pet trade for terrapins. We don't know how many are taken from the wild for this. Some people breed them in captivity. Certain color types are very popular. In Europe, Malaclemys are often kept as pets.

Terrapins and People

In Maryland, diamondback terrapins were so common in the 1700s that slaves complained about eating them too often. Later, in the late 1800s, there was a huge demand for turtle soup. In one year, 89,150 pounds of terrapins were caught from Chesapeake Bay. In 1899, Delmonico's Restaurant in New York City offered terrapin on its menu. It was the third most expensive item, costing $2.50. By 1920, so many terrapins had been caught that the yearly harvest was only 823 pounds.

From 1990 to 2007, 18 incidents were reported where diamondback terrapins hit civil aircraft in the US. None of these caused damage to the planes. On July 8, 2009, flights at John F. Kennedy International Airport in New York City were delayed. This was because 78 diamondback terrapins were on one of the runways. Airport authorities believed the turtles came onto the runway to nest. They were removed and safely returned to the wild. A similar event happened on June 29, 2011, when over 150 turtles crossed runway 4. This closed the runway and stopped air traffic. Those terrapins were also moved safely.

The Port Authority of New York and New Jersey built a barrier along runway 4L at JFK. This was to reduce the number of terrapins on the runway and encourage them to nest elsewhere. However, on June 26, 2014, 86 terrapins still got onto the same runway. A high tide carried them over the barrier. The number of terrapins at the airport is affected by the raccoon population. When raccoons decrease, more terrapins mate, leading to more turtle activity at the airport.

Many human activities threaten diamondback terrapins. They get caught and drown in crab nets. They can be harmed by pollution that humans create. They also lose their marsh and estuary homes because of city development.

Terrapins as a Special Food

Diamondback terrapins were heavily hunted for food in colonial America. Native Americans probably ate them before that too. Terrapins were so common and easy to catch that slaves and even the Continental Army ate many of them.

In the 1800s, a dish called "Terrapin à la Maryland" was very popular. It was a stew with cream and sherry. This dish was a key part of fancy "Maryland Feast" menus for decades.

By 1917, terrapins sold for as much as $5 each. Huge numbers of terrapins were caught from marshes and sold in cities. By the early 1900s, terrapin populations in the northern areas were very low. Southern populations were also greatly reduced. As early as 1902, the U.S. Bureau of Fisheries realized that terrapin numbers were dropping. They started building large research centers to find ways to breed terrapins in captivity for food. People tried to establish them in many other places, but it didn't work.

Terrapins as a Symbol

Maryland made the diamondback terrapin its official state reptile in 1994. The University of Maryland, College Park uses the species as its nickname (the Maryland Terrapins) and mascot (Testudo) since 1933. The school newspaper has been named The Diamondback since 1921. The athletic teams are often called "Terps" for short.

The Baltimore baseball team in the Federal League in 1914 and 1915 was called the Baltimore Terrapins. The terrapin has also been a symbol for the band Grateful Dead. This is because of their song "Terrapin Station". Many pictures of the terrapin dancing with a tambourine appear on posters and T-shirts related to the Grateful Dead. Inspired by the song, the Terrapin Beer Company uses a terrapin as its name and logo.

- Species Malaclemys terrapin at The Reptile Database

Images for kids

-

Texas diamond-backed terrapin (Malaclemys terrapin littoralis), Galveston County, Texas (8 May 2008)

See also

In Spanish: Tortuga espalda de diamante para niños

| Jewel Prestage |

| Ella Baker |

| Fannie Lou Hamer |