List of U.S. state reptiles facts for kids

Twenty-eight U.S. states have chosen an official state reptile. Just like other state symbols, these reptiles are picked because they show something special or admirable about the state. Often, schoolchildren start campaigns to convince their state lawmakers to choose their favorite reptile as a symbol! Many state government websites have fun pages that teach about their state reptile.

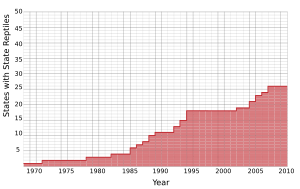

Oklahoma was the very first state to name an official reptile, the common collared lizard, in 1969. Only two more states picked one in the 1970s. But after that, states started choosing them much more often, almost one every year! State birds are even more common, with all 50 states having one. They were adopted earlier, with the first one chosen in 1927.

Some state reptiles were already famous before they became official symbols. For example, Florida's American alligator, Maryland's diamondback terrapin, and Texas's Texas horned lizard were all mascots for big universities in those states. West Virginia's timber rattlesnake was even part of an early American flag way back in 1775!

Reptiles are "cold-blooded," meaning their body temperature depends on their surroundings. So, they are more common in warmer places. That's why 19 of the 28 state reptiles are found in southern states. Six states chose a reptile named after their state. More than half of the states picked a turtle. The most popular choice, picked by four states, is the painted turtle. One state reptile, the bog turtle, is critically endangered, which means it's in great danger of disappearing forever. The Alabama red-bellied turtle is also officially listed as an endangered species in the United States. Several other turtles are also threatened at different levels.

Contents

State Reptiles Across the U.S.

| State | State Reptile | Scientific Name | Year Adopted | Conservation Status | Photograph | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alabama | Alabama red-bellied turtle | Pseudemys alabamensis | 1990 | Endangered |  |

|

| Arizona | Arizona ridge-nosed rattlesnake | Crotalus willardi subspecies willardi |

1986 | Least Concern |  |

|

| California | Desert tortoise (state reptile) |

Gopherus agassizii | 1972 | Vulnerable |  |

|

| Leatherback sea turtle (state marine reptile) |

Dermochelys coriacea | 2012 | Vulnerable |  |

||

| Colorado | Western painted turtle | Chrysemys picta subspecies bellii |

2008 | Least Concern |  |

|

| Florida | American alligator (state reptile) |

Alligator mississippiensis | 1987 | Least Concern |  |

|

| Loggerhead sea turtle (state saltwater reptile) |

Caretta caretta | 2008 | Vulnerable |  |

||

| Gopher tortoise (state tortoise) |

Gopherus polyphemus | 2008 | Vulnerable |  |

||

| Georgia | Gopher tortoise | Gopherus polyphemus | 1989 | Vulnerable |  |

|

| Illinois | Painted turtle | Chrysemys picta | 2005 | Least Concern |  |

|

| Kansas | Ornate box turtle | Terrapene ornata | 1986 | Near Threatened |  |

|

| Louisiana | American alligator | Alligator mississippiensis | 1983 | Least Concern |  |

|

| Maryland | Diamondback terrapin | Malaclemys terrapin | 1994 | Near Threatened |  |

|

| Massachusetts | Garter snake | Thamnophis (whole genus) |

2006 | Least Concern |  |

|

| Michigan | Painted turtle | Chrysemys picta | 1995 | Least Concern |  |

|

| Minnesota | Blanding's turtle | Emydoidea blandingii | 1998, proposed | Endangered |  |

|

| Mississippi | American alligator | Alligator mississippiensis | 2005 | Least Concern |  |

|

| Missouri | Three-toed box turtle | Terrapene carolina subspecies triunguis |

2007 | Near Threatened |  |

|

| Nevada | Desert tortoise | Gopherus agassizii | 1989 | Vulnerable |  |

|

| New Jersey | Bog turtle | Glyptemys muhlenbergii | 2018 | Critically endangered | ||

| New Mexico | New Mexico whiptail lizard | Cnemidophorus neomexicanus | 2003 | Least Concern |  |

|

| New York | Common snapping turtle | Chelydra serpentina | 2006 | Least Concern |  |

|

| North Carolina | Eastern box turtle | Terrapene carolina subspecies carolina |

1979 | Near Threatened |  |

|

| Ohio | Northern black racer | Coluber constrictor subspecies constrictor |

1995 | Least Concern |  |

|

| Oklahoma | Common collared lizard | Crotaphytus collaris | 1969 | Least Concern |  |

|

| South Carolina | Loggerhead sea turtle | Caretta caretta | 1988 | Vulnerable |  |

|

| Tennessee | Eastern box turtle | Terrapene carolina subspecies carolina |

1995 | Near Threatened |  |

|

| Texas | Texas horned lizard (state reptile) |

Phrynosoma cornutum | 1993 | Least Concern |  |

|

| Kemp's ridley sea turtle (state sea turtle) |

Lepidochely kempii | 2013 | Critically Endangered |  |

||

| Utah | Gila monster | Heloderma suspectum | 2019 | Near Threatened |  |

|

| Vermont | Painted turtle | Chrysemys picta | 1994 | Least Concern |  |

|

| Virginia | Eastern garter snake (state snake) |

Thamnophis sirtalis subspecies sirtalis |

2016 | Least Concern |  |

|

| West Virginia | Timber rattlesnake | Crotalus horridus | 2008 | Least Concern |  |

|

| Wyoming | Horned lizard | Phrynosoma (whole genus) |

1993 | Least Concern |  |

How State Reptiles Are Chosen

The Lawmaking Process

A reptile becomes an official state symbol after the state legislature votes for it. In many states, the governor also needs to sign the bill into law. But in some places, it just needs a vote from the legislature. For example, in 2004, Illinois held a public vote to pick the painted turtle. But a law was still needed in 2005 to make it official.

Often, schoolchildren are the ones who start the campaigns for state reptiles. Three of the four states that chose the painted turtle say that school classes began the process. Students might even need to be experts on their chosen reptile! In Florida, students who wanted the loggerhead sea turtle had to give information and answer questions for lawmakers. In New York, students across the state voted for one of four turtles. The common snapping turtle won by a very close vote (5,048 to 5,005) against the painted turtle. A lawmaker named Joel Miller sponsored the turtle election to get students interested in politics. He said the results showed that "every vote is important."

Not all reptiles suggested by students make it through the lawmaking process. In Minnesota, bills to make the Blanding's turtle the state reptile failed in 1998 and 1999. In Pennsylvania in 2009, a bill for the eastern box turtle passed in one part of the legislature but didn't get a vote in the other. In Virginia, attempts to make the eastern box turtle the state reptile failed in 1999 and 2009. For the most recent try, one lawmaker said the turtle was too "cowardly" because of its shell and suggested the rattlesnake instead. The turtle was also criticized for often dying on roads. But its biggest problem was being too similar to North Carolina's state reptile.

Why States Choose Them

Like other state symbols, a state reptile is meant to show state pride. Choosing a state reptile doesn't usually help with the economy or protect wildlife directly. States explain why they chose their reptile in their laws and on their websites:

- North Carolina picked the eastern box turtle because its behavior shows good human qualities. They said the turtle "watches undisturbed as countless generations of faster 'hares' run by... and is thus a model of patience for mankind."

- Maryland points to its history with the diamondback terrapin. Early settlers ate terrapins, and later, in the 1800s, they became a fancy food.

- Ohio praises its reptile for being common and helpful. The black racer snake was chosen because it lives in all 88 Ohio counties. It's called the "farmer's friend" because it eats rodents that carry diseases.

- Texas highlights the need to protect the Texas horned lizard. They said it's a good symbol because, "like many other things truly Texan, it is a threatened species."

Educational Uses

The idea of a state reptile is great for education. Some states offer lesson plans for teachers to use the reptile to teach kids about how laws are made, state geography, or state pride. Many state government websites have "kids pages" that describe the reptile. Some, like Missouri's Robin Carnahan, even offer coloring books!

How Many Reptiles Are Adopted?

In 1969, Oklahoma chose the common collared lizard, also called the "mountain boomer," as the first state reptile. Two states followed in the 1970s, seven in the 1980s, eight in the 1990s, and eight in the 2000s. As of March 2019, 28 of the 50 states have named a state reptile. Utah and New Jersey both adopted one in the 2010s.

Compared to state reptiles, state birds were adopted much faster. The first state chose a bird in 1927, and all 50 states had one by 1973. As of 2011, other animal symbols more popular than reptiles included mammals (46 states), fish (45 states), and insects (42 states). Animals less popular than reptiles were butterflies (17), amphibians (17), dogs (11), dinosaurs (5), bats (3), and crustaceans (3).

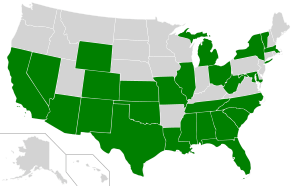

Where State Reptiles Are Found

Since reptiles are cold-blooded, they are more common in warmer places. That's why states in the southern half of the United States have chosen state reptiles more often. Out of the 24 states in the southern part of the country, only four don't have a state reptile: Delaware, Virginia, Kentucky, and Arkansas.

In the northern half of the central and western states, only Wyoming has named a state reptile. In the Great Lakes area, Illinois, Michigan, and Ohio have chosen reptiles. In the Northeast, Massachusetts, New York, and Vermont have also picked one.

Neither Alaska nor Hawaii have named a state reptile. The District of Columbia doesn't have a "state" reptile, though it does have an official tree and flower. None of the U.S. territories have state reptiles either, but all four have chosen official flowers.

Six states picked reptiles named after their state. For example, Arizona chose the Arizona ridge-nosed rattlesnake, and Texas chose the Texas horned lizard. Mississippi and North Carolina have reptiles whose scientific names include their state names: Alligator mississippiensis and Terrapene carolina carolina. Alabama and New Mexico have reptiles named after them in both common names (Alabama red-bellied turtle and New Mexico whiptail lizard) and scientific names (Pseudemys alabamensis and Cnemidophorus neomexicanus).

Reptiles in History and Sports

Reptiles and American History

Even though there is no official reptile for the entire United States, some state reptiles have played a role in American history. The timber rattlesnake (West Virginia) has a strong connection to American independence.

A U.S. flag with a timber rattlesnake was used even before the famous stars and stripes flag. In 1775, Christopher Gadsden created a flag with a coiled rattlesnake and the words "Don't tread on me" on a yellow background. This Gadsden flag was used by early American naval forces and soldiers.

The timber rattlesnake also appeared on the First Navy Jack, a red and white striped flag. Although it was thought to be used by the early U.S. Navy, some historians now say the snake on that flag was added later. Still, in 1975, the U.S. Navy brought back the traditional snake flag for its 200th birthday. Since 2002, after the 9/11 terrorist attacks, all U.S. Navy ships have used the First Navy Jack.

| Gadsden Flag | First Navy Jack |

|---|---|

|

|

When West Virginia named the timber rattlesnake its state reptile in 2008, a state wildlife magazine article in 2009 connected it to the old American rattlesnake symbol. The article explained that the rattlesnake on early flags wasn't meant to show Americans as fierce. Instead, it meant that Americans were peaceful and loved freedom. But if King George III of England kept being unfair, they would fight back strongly. Just like a rattlesnake, which is calm but will attack fiercely if provoked.

Benjamin Franklin wrote in 1775 that the rattlesnake "never begins an attack, nor, when once engaged, ever surrenders: She is therefore an emblem of magnanimity and true courage...she never wounds ‘till she has generously given notice."

Not all political uses of reptiles have been positive. The snapping turtle (New York) was in a famous American political cartoon in 1808. It showed a snapping turtle biting a trader who was trying to sneak goods onto a British ship. The trader said, "Oh! this cursed Ograbme" (which is "embargo" spelled backward). This cartoon criticized a law called the Embargo Act of 1807. Also, during the Great Depression, the gopher tortoise (Georgia, Florida's official tortoise) was jokingly called the "Hoover chicken." This was because poor people ate them when they couldn't find other food.

Reptiles as Sports Mascots

Three states chose reptiles that were already popular mascots for big universities in their state:

- Florida honored the American alligator in 1987. But the Gators have been the name for the University of Florida's teams since 1911. That year, a printer decided to put an alligator picture on the school's football flags. The mascot stuck, partly because the team captain's nickname was "Gator."

- Maryland honored the diamondback terrapin in 1994. But the mascot for the main state university in College Park has been the Terrapins or "Terps" since 1932. The football coach, who had seen these turtles as a boy, suggested it as a mascot.

- Texas honored the Texas horned lizard in 1993. But Texas Christian University has had the Horned Frog as its mascot since 1896. Legend says the football team felt a connection to the feisty lizards they found on their practice field. The college founder's son, Addison Clark Jr., who started the football team, was fascinated by these creatures. By 1897, the lizard was even on the front of the school yearbook.

Types of State Reptiles

When we look at the main groups of reptiles, turtles are the most popular choice. Fifteen of the 27 states have chosen a turtle as their official reptile. The other state reptiles include four snakes, five lizards, and three crocodilians (like alligators). Eighteen states named a reptile at the species level, two named a whole genus (a group of species), and seven named a subspecies (a group within a species).

The painted turtle is the most popular choice, picked by four states: Colorado (a specific type of painted turtle), Illinois, Michigan, and Vermont. Three southern states—Florida, Louisiana, and Mississippi—chose the American alligator. A type of box turtle, Terrapene carolina (common box turtle), has been chosen by three states. North Carolina and Tennessee use the Terrapene carolina carolina (eastern box turtle) subspecies. Missouri uses the Terrapene carolina triunguis (three-toed box turtle) subspecies. Two neighboring western states, California and Nevada, chose the desert tortoise. The loggerhead sea turtle was named by South Carolina as its state reptile, while Florida chose it as its state saltwater reptile. Florida also named an official tortoise, the gopher tortoise, which is the same animal as Georgia's state reptile.

Four genera (groups of species) are represented by different species on the list. Terrapene (box turtles) includes Terrapene ornata (Kansas) along with Terrapene carolina (Missouri, North Carolina, and Tennessee). Under Gopherus (gopher tortoises), there are Gopherus polyphemus (Georgia's state reptile and Florida's state tortoise) and Gopherus agassizii (California and Nevada). Under Crotalus (one of two rattlesnake genera), Arizona named Crotalus willardi willardi, while West Virginia chose Crotalus horridus. With Phrynosoma (horned lizards), Wyoming chose the entire genus, but Texas picked Phrynosoma cornutum.

Protecting State Reptiles

Reptile Declines and State Reptile Examples

| 1953 Golden Guide | 2001 Golden Guide |

|---|---|

| "As a group [reptiles] are neither 'good' nor 'bad', but are interesting and unusual, although of minor importance. If they should all disappear it would not make much difference one way or another." | "Reptiles and amphibians are an important part of the environment...They help control harmful pests and are prey for other creatures. Needless killing...must stop. Wild areas...should be preserved." |

In 1988, a naturalist named J. Whitfield Gibbons said that people weren't as aware of the need to protect reptiles as they were for large mammals or game animals. However, if you compare different editions of the Golden Guide (a series of nature books), you can see that people became more aware of reptile conservation in the second half of the 20th century.

In 2000, Gibbons and his team wrote that even though people might feel more sympathy for amphibians (maybe because of their soft skin), reptile species are actually more endangered. While animal populations can decrease naturally, human actions cause most of the problems for reptile species. Gibbons and his team listed six reasons why reptile numbers are going down. Here are some examples that include state reptile species:

- Overharvesting. This means too many animals are collected by humans. It has greatly harmed many reptile species, especially turtles. The diamondback terrapin (Maryland) was once very common but its numbers dropped sharply in the early 1900s because it was popular in soup. Its numbers are slowly recovering now that people mostly stopped harvesting them for food. Collecting box turtles (Kansas, Missouri, North Carolina, Tennessee) for the pet trade has also caused their numbers to drop. The timber rattlesnake (West Virginia) is threatened by "rattlesnake roundups" because females take nine years to grow up and only have about four babies a year. However, not all human use of reptiles is harmful. Since the late 1900s, the American alligator (Florida, Louisiana, Mississippi) has recovered. Its numbers are now managed well with hunting rules and commercial farms.

- Habitat loss. This means animals lose their homes. Gopher tortoises (Georgia, Florida's official tortoise) have been affected by the loss of 97% of the Southeast's longleaf pine forest.

- Introduced invasive species. New plant species have harmed the desert tortoise (California, Nevada) and gopher tortoise (Georgia, Florida's official tortoise). Fire ants, which eat eggs, have reduced the Texas horned lizard (Texas) in some areas.

- Environmental pollution. Water pollution mainly affects turtles and crocodilians. It can harm their eggs and even change whether their babies are male or female. Male American alligators (Florida, Louisiana, Mississippi) have been found with lower testosterone in lakes with chemical pollution.

- Disease. More diseases in wild animals often happen when they are already weakened by other problems, like losing their habitat. Lung infections and shell diseases have been linked to the decline of the desert tortoise (California, Nevada) and gopher tortoise (Georgia, Florida's state tortoise).

- Climate change is a future threat because it changes habitats. Reptiles are more at risk than birds because they can't travel long distances easily. Gibbons and his team didn't give specific examples for state reptiles, but they are worried about turtles and crocodilians. Their babies' sexes are determined by the temperature of their eggs, so changing temperatures could cause problems.

IUCN Conservation Ratings

Because of the general problems reptiles face, some U.S. state reptiles are dwindling in numbers. The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) has a system of ratings for species, from "Extinct" to "Least Concern." None of the U.S. state reptiles are in the most extreme categories like "Extinct" or "Extinct in the Wild."

Two species are rated "Endangered" by the IUCN: the Alabama red-bellied turtle (Alabama) and the loggerhead sea turtle (South Carolina, also Florida's state saltwater reptile). However, in the United States, only the Alabama red-bellied turtle is legally an endangered species. The loggerhead sea turtle is considered "threatened" under U.S. rules.

Two species are "Vulnerable" according to the IUCN: the desert tortoise (California and Nevada) and the gopher tortoise (Georgia, also Florida's official tortoise). Three species are "Near Threatened": the diamondback terrapin (Maryland), the ornate box turtle (Kansas), and the common box turtle (Missouri, North Carolina, and Tennessee). All the other state reptile species are rated "Least Concern," meaning they are not currently at high risk. All the non-turtle reptiles are in this category. The only two turtles in this safe category are the common snapping turtle (New York) and the painted turtle (Colorado, Illinois, Michigan, Vermont).

The IUCN ratings for state reptiles usually apply to the whole species. For most state reptiles, the IUCN doesn't have separate ratings for subspecies. For example, with the Arizona ridge-nosed rattlesnake, the IUCN notes that the subspecies is about as safe as the overall species, but it doesn't give a formal rating for just the subspecies.

These ratings also don't always show how well a reptile population is doing in a specific state. For instance, the Texas horned lizard has disappeared from much of eastern Texas. But because there are healthy populations in other parts of the West, especially New Mexico, the IUCN rates the animal as "Least Concern." For the timber rattlesnake (West Virginia), the IUCN notes that the animal is losing ground in many parts of the northeastern U.S. But because there are many of them in the southern Appalachian mountains, it's also rated "Least Concern."

The IUCN status for state reptiles chosen at the genus level can be a bit unclear. For Massachusetts's garter snake, the "Least Concern" rating refers to the common garter snake, which is found throughout much of North America and lives in Massachusetts. Within that genus, there are 23 species at "Least Concern," and two each at "Vulnerable," "Endangered," and "Data Deficient" (meaning there isn't enough information). For Wyoming's horned lizard state reptile, the rating reflects the short-horned lizard, which lives across much of the central United States and almost all of Wyoming. Within that genus, there are ten species at "Least Concern," one at "Near Threatened," and one at "Data Deficient."

| Jewel Prestage |

| Ella Baker |

| Fannie Lou Hamer |