Mark Lane (author) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Mark Lane

|

|

|---|---|

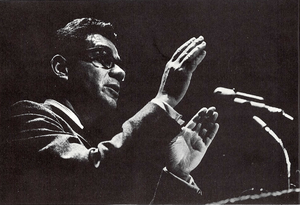

Mark Lane in Ann Arbor, 1967

|

|

| Member of the New York State Assembly from New York County's 10th District |

|

| In office 1 January 1961 – 31 December 1962 |

|

| Preceded by | Martin J. Kelly, Jr. |

| Succeeded by | Carlos M. Rios |

| Personal details | |

| Born | February 24, 1927 The Bronx, New York, U.S. |

| Died | May 10, 2016 (aged 89) Charlottesville, Virginia, U.S. |

| Nationality | American |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Other political affiliations |

Freedom and Peace (1968) |

| Known for | Conspiracy theorist on the Assassination of John F. Kennedy |

|

Notable work

|

Rush to Judgment Plausible Denial Executive Action |

Mark Lane (February 24, 1927 – May 10, 2016) was an American lawyer, politician, and civil rights activist. He also investigated war-crimes during the Vietnam War. Lane is best known for his research and books about the killing of U.S. President John F. Kennedy. His 1966 book, Rush to Judgment, questioned the official report on the assassination. He wrote several books on the topic, including Last Word: My Indictment of the CIA in the Murder of JFK in 2011.

Contents

Early Life and Career

Mark Lane was born in The Bronx, New York, and grew up in Brooklyn, New York. He served in the United States Army after World War II from 1945 to 1946. He was stationed in Austria during this time. After his military service, he went to Long Island University. He then earned a law degree from Brooklyn Law School in 1951.

After becoming a lawyer, Lane started a law practice in East Harlem. He became known as a lawyer who helped people who were poor or treated unfairly. In 1959, Lane helped create the Reform Democrat movement in the New York Democratic Party. He was elected to the New York State Assembly in 1960. This was a state-level political job. He served in the Assembly in 1961 and 1962. While in office, he worked to end capital punishment, also known as the death penalty.

In 1961, Lane was arrested for protesting against segregation. He was a Freedom Rider, which meant he rode buses to challenge unfair laws that separated people by race. In 1968, he ran for Vice President of the United States. He was a candidate for the Freedom and Peace Party.

Investigating the Kennedy Assassination

The Warren Commission Report

After President John F. Kennedy was killed, a group called the Warren Commission investigated the event. Mark Lane wrote a letter to the head of this group, Chief Justice Earl Warren. Lane asked if he could represent Lee Harvey Oswald, who was accused of the assassination. Lane also wrote an article called "Oswald Innocent? A Lawyer’s Brief." This article questioned the official claims about the assassination.

Oswald's mother, Marguerite Oswald, read Lane's article and hired him to represent her son. However, the Warren Commission did not allow Lane to be Oswald's lawyer. They said they had already appointed another lawyer to represent Oswald's interests. Lane still considered himself Oswald's lawyer. He testified before the Warren Commission in 1964. During his testimony, Lane questioned some of the evidence.

Lane's work on the assassination led others, like Bertrand Russell, to support new investigations. In 1975, Lane became the director of the Citizens Commission of Inquiry (CCI). This group questioned the official stories about the assassination.

Rush to Judgment Book

Lane's book, Rush to Judgment, was published in 1966. It became a number one best-seller. The book strongly criticized the Warren Commission's investigation and its findings. Lane questioned if three shots were fired from the Texas School Book Depository. He focused on witnesses who said they saw or heard shots from the grassy knoll. Lane also questioned if Oswald killed policeman J.D. Tippit. He pointed out that experts could not copy Oswald's supposed shooting skills.

Some people, like former Texas Governor John Connally, criticized Lane's book. Lane said Connally did not understand the facts. A former KGB officer claimed the KGB helped fund Lane's research for the book. Lane denied this, calling the claim "an outright lie."

Other Books and Films

Lane wrote other books about the Kennedy assassination. These included A Citizen's Dissent. He also helped write the first version of the screenplay for the 1973 film Executive Action. This movie starred Burt Lancaster. Lane later said he only worked on the first draft of the script.

In 1991, Lane published Plausible Denial. He said this would be his "last word" on the topic. However, in 2011, he published another major book called Last Word: My Indictment of the CIA in the Murder of JFK.

Legal Cases

Mark Lane worked as a lawyer on several important cases. He represented a group called Liberty Lobby in a lawsuit. The group was sued over an article that said E. Howard Hunt was involved in the Kennedy assassination. Lane successfully helped overturn a large fine against Liberty Lobby. This case became the basis for his book Plausible Denial.

In 1995, Lane sued the book publisher Random House. They had used his photo with a caption that said he was "Guilty of Misleading the American Public." This was in an advertisement for another book. Lane lost this lawsuit. The judge said that someone who strongly questions official stories should expect some criticism.

Martin Luther King Jr. Assassination

Lane also wrote about the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr.. His book, Murder In Memphis, suggested a conspiracy and government cover-up. Lane represented James Earl Ray, who was accused of killing King. Lane argued that Ray was innocent and was part of a larger government plot. He created an audio play called Trial of James Earl Ray that questioned Ray's guilt.

Later Life and Legacy

In 1970, Lane wrote a book called Arcadia. This book was about James Joseph Richardson, a man wrongly accused of killing his seven children in Florida. Richardson had been on death row for many years. Thanks to Lane's efforts, Richardson received a new hearing. The charges were dropped, and he was released from prison after 21 years. Later, Richardson's babysitter confessed to the murders.

Mark Lane lived in Charlottesville, Virginia. He continued to work as a lawyer and gave talks on important topics. He often spoke about the United States Constitution, especially the Bill of Rights and the First Amendment. He also spoke about civil rights.

In 2001, Lane was recognized as one of twelve important legal figures. This was at a special event held by the Law Library of Congress. Mark Lane died from a heart attack at his home on May 10, 2016, at the age of 89.

Images for kids

| Emma Amos |

| Edward Mitchell Bannister |

| Larry D. Alexander |

| Ernie Barnes |