Maury Wills facts for kids

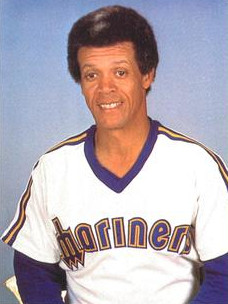

Quick facts for kids Maury Wills |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

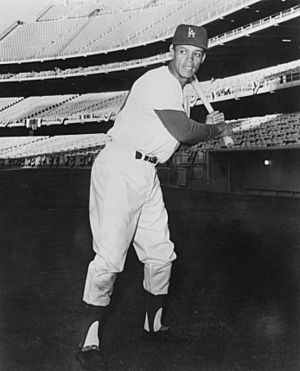

Wills with the Los Angeles Dodgers in 1961

|

|||

| Shortstop/Manager | |||

| Born: October 2, 1932 Washington, D.C. |

|||

| Died: September 19, 2022 (aged 89) Sedona, Arizona |

|||

|

|||

| debut | |||

| June 6, 1959, for the Los Angeles Dodgers | |||

| Last appearance | |||

| October 4, 1972, for the Los Angeles Dodgers | |||

| MLB statistics | |||

| Batting average | .281 | ||

| Hits | 2,134 | ||

| Home runs | 20 | ||

| Runs batted in | 458 | ||

| Stolen bases | 586 | ||

| Managerial record | 26–56 | ||

| Winning % | .317 | ||

| Teams | |||

As player

As manager

|

|||

| Career highlights and awards | |||

|

|||

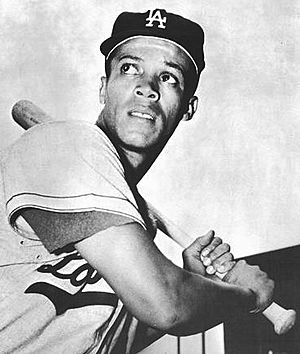

Maurice "Maury" Morning Wills (born October 2, 1932 – died September 19, 2022) was an American professional baseball player and manager. He played in Major League Baseball (MLB) mostly for the Los Angeles Dodgers. He was a shortstop and could hit from both sides of the plate (a switch-hitter).

Maury Wills was a key player for the Dodgers' championship teams in the mid-1960s. He is famous for bringing back the stolen base as an important part of baseball strategy. In 1962, he was named the National League Most Valuable Player (MVP). That year, he stole an amazing 104 bases, breaking a record that had stood since 1915.

He was also an All-Star seven times and won two Gold Glove Awards for his excellent fielding. In his 14-year career, Wills had a .281 batting average and stole 586 bases. After playing, he also managed the Seattle Mariners.

Contents

Early Life and Baseball Dreams

Maury Wills was born in Washington, D.C.. He was the seventh of 13 children in his family. He started playing semi-professional baseball when he was just 14 years old.

At Cardozo Senior High School, he played baseball, basketball, and football. He was named an All-City player in all three sports during his sophomore, junior, and senior years. Wills graduated from Cardozo in 1950.

Maury Wills' Professional Baseball Journey

Starting in the Minor Leagues

After high school, Wills signed with the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1950. He spent eight years playing in the minor leagues. Before the 1959 season, the Detroit Tigers bought his contract. However, they sent him back to the Dodgers after spring training, thinking he wasn't worth the price.

Becoming a Los Angeles Dodger Star

The Dodgers' longtime shortstop, Pee Wee Reese, retired after the 1958 season. The team tried a few players at shortstop. When Don Zimmer got hurt in June 1959, the Dodgers called up Maury Wills from the minor leagues.

Wills played in 83 games for the Dodgers that year. He helped them win the 1959 World Series, playing in all six games. In his first full season in 1960, he hit .295 and led the league with 50 stolen bases. He was the first National League player to steal 50 bases since 1923.

In 1962, Wills made history by stealing 104 bases. This broke the modern MLB record of 96, set by Ty Cobb in 1915. Wills stole more bases than any entire team that year! He was only caught stealing 13 times. He also hit .299 and led the NL with 10 triples.

During the 1962 season, the San Francisco Giants manager even tried to make the base paths muddy to stop Wills from stealing. Wills played an incredible 165 games that year, which is still an MLB record for most games in a single season. His 104 stolen bases remained a record until Lou Brock stole 118 in 1974. Wills won the NL Most Valuable Player Award over Willie Mays.

Wills continued to shine in the World Series. He helped the Dodgers win in 1963 and 1965, earning his third and final World Series title. He was a Gold Glove Award winner in 1961 and 1962 and was named a NL All-Star five times.

Playing for Other Teams

After the 1966 season, the Dodgers traded Wills to the Pittsburgh Pirates. In 1967, he had a .302 batting average and stole 29 bases. In 1968, he stole 52 bases.

In 1968, the Montreal Expos picked Wills in the expansion draft. He was the first player to bat for the Expos in their first game on April 8, 1969. He played only 47 games for them before being traded back to the Dodgers.

Returning to the Dodgers

On June 11, 1969, Wills returned to the Dodgers. He played well, hitting .297 and stealing 25 bases that year. He continued to be a strong player for the Dodgers until 1972. In his final MLB appearance on October 4, 1972, he scored a run as a pinch runner. He was released by the Dodgers later that month.

The Art of Stealing Bases

Maury Wills, along with Luis Aparicio, brought new attention to the stolen base. Wills was a constant threat when he got on base. Fans at Dodger Stadium would chant, "Go! Go! Go, Maury, Go!" whenever he reached base.

Wills was not always the fastest runner, but he could accelerate very quickly. He also studied pitchers carefully, watching their moves even when he wasn't on base. His strong competitive spirit made him determined to steal. Once, he made a pitcher throw to first base 12 times before he finally stole second base!

Even though his stolen base numbers dropped after his record-breaking year, Wills continued to make pitchers nervous. He would bandage his legs before every game because of the impact of sliding.

Life After Playing Baseball

After retiring as a player, Maury Wills worked as a baseball analyst for NBC. He also managed in the Mexican Pacific League, winning a championship in 1970–71.

In August 1980, the Seattle Mariners hired Wills as their manager. However, his time as a manager was short and challenging. He made some mistakes, like calling for a relief pitcher when no one was ready. He also once ordered the grounds crew to make the batter's box longer, which was against the rules. He was suspended for two games and fined for this.

The Mariners fired Wills in May 1981. His record as a manager was 26 wins and 56 losses.

Despite his struggles as a manager, Wills was a great teacher of base stealing. Players like Julio Cruz and Dave Roberts have said that Wills taught them how to steal bases under pressure.

Wills continued to be involved with baseball. He coached for the Dodgers and served as a radio commentator. He also returned to the Dodgers as a guest instructor in spring training.

In 2014, Wills was considered for the National Baseball Hall of Fame, but he did not receive enough votes. He was again on the ballot in 2022 but was not elected.

Music and Personal Life

During his baseball career, Wills also had a passion for music. In the off-season, he performed as a singer and played the banjo, guitar, and ukulele. He even released some records. For a couple of years, he owned a nightclub in Pittsburgh called "The Stolen Base."

Wills was married to Angela George. He is the father of Bump Wills, who also played in Major League Baseball for six seasons.

In 2009, a baseball field in Washington, D.C., was renamed Maury Wills Field in his honor. A museum dedicated to him also opened in Fargo, North Dakota, in 2001, closing in 2017.

Maury Wills passed away at his home in Sedona, Arizona, on September 19, 2022, at the age of 89.

Other Awards and Honors

- Hickok Belt Award (1962)

- The Baseball Reliquary's Shrine of the Eternals (class of 2011)

- "Legends of Dodger Baseball" (2022)

The Stolen Base Record "Asterisk"

When Maury Wills broke Ty Cobb's stolen base record in 1962, the National League had increased its season from 154 games to 162 games. Wills stole his 97th base after his team had played 154 games.

Because of this, Commissioner Ford Frick decided that Wills' 104-steal season and Cobb's 96-steal season were separate records. This was similar to how Roger Maris's home run record was handled the year before. Both of these stolen base records were later broken by Lou Brock in 1974, who stole 118 bases.

See also

- List of Major League Baseball career hits leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career runs scored leaders

- List of Major League Baseball stolen base records

- List of Major League Baseball career stolen bases leaders

- List of Major League Baseball annual stolen base leaders

- List of Major League Baseball annual triples leaders

- Major League Baseball titles leaders

Images for kids