Max Frisch facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Max Frisch

|

|

|---|---|

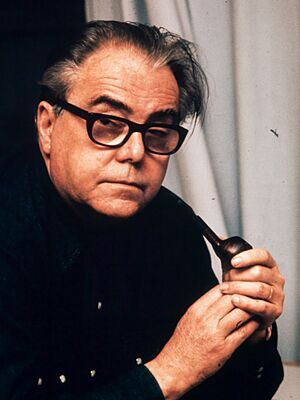

Frisch c. 1974

|

|

| Born | Max Rudolf Frisch 15 May 1911 Zürich, Switzerland |

| Died | 4 April 1991 (aged 79) Zürich, Switzerland |

| Occupation | Architect, novelist, playwright, philosopher |

| Language | German |

| Nationality | Swiss |

| Spouse | Gertrud Frisch-von Meyenburg (married 1942, separated 1954, divorced 1959) Marianne Oellers (married 1968, divorced 1979) |

| Partner | Ingeborg Bachmann (1958–1963) |

Max Rudolf Frisch (15 May 1911 – 4 April 1991) was a famous Swiss writer. He wrote plays and novels. Frisch's stories often explored big questions. These included what makes us who we are, being an individual, and what it means to be responsible. He also wrote about right and wrong, and how people should act in society.

Max Frisch was known for using irony in his writing after World War II. He helped start a group of writers called Gruppe Olten. He won many important awards for his work. These included the Jerusalem Prize in 1965 and the Neustadt International Prize for Literature in 1986.

Contents

Max Frisch's Early Life and School

Max Rudolf Frisch was born in Zürich, Switzerland, on May 15, 1911. He was the second son of Franz Bruno Frisch, who was an architect. His mother was Karolina Bettina Frisch. Max had an older sister, Emma, and an older brother, Franz.

His family did not have a lot of money. Things got harder when his father lost his job during World War I. Max was not very close to his father. But he had a strong bond with his mother.

While in high school, Max Frisch started writing plays. However, his early works were never performed. He later destroyed these first writings. During this time, he met Werner Coninx, who became a successful artist. They became lifelong friends.

In 1930, Frisch went to the University of Zurich. He studied German literature and language. He met professors who helped him connect with publishers and journalists. He hoped university would teach him how to be a writer. But he soon felt it wasn't the right path. In 1932, he left his studies because his family needed more money.

Later, in 1936, Max Frisch decided to study architecture. He went to the ETH Zurich and finished his degree in 1940. In 1942, he even started his own architecture business.

Max Frisch's Career

Journalism and Early Writing

Max Frisch began writing for the newspaper Neue Zürcher Zeitung (NZZ) in 1931. When his father died in 1932, he became a full-time journalist. This helped him earn money to support his mother. He had a complicated relationship with the NZZ. His later, more modern ideas were very different from the newspaper's traditional views.

His first serious freelance writing was an essay called "What am I?" in 1932. Until 1934, he balanced journalism with his university studies. Many of his writings from this time were about his own life. They explored his personal experiences.

Between 1933 and 1934, Frisch traveled a lot. He visited countries in Eastern and Southeastern Europe. He paid for his trips by writing reports for newspapers. One of his first reports was about a hockey championship in Prague. He also visited cities like Budapest, Istanbul, and Rome.

His first novel, Jürg Reinhart, came out in 1934. In this book, the main character, Jürg Reinhart, is like Frisch himself. He travels through the Balkans to find meaning in his life.

Meeting Käte Rubensohn and Visiting Germany

In 1934, Frisch met Käte Rubensohn. She was Jewish and had moved from Berlin to Switzerland. She had to leave Germany because of unfair laws against Jewish people.

In 1935, Frisch visited Nazi Germany for the first time. He kept a diary about his trip. He wrote about and criticized the unfair treatment of Jewish people he saw. At the same time, he admired an art exhibition there. Frisch did not fully understand how bad Nazism would become. His early books were published in Germany without problems.

In the 1940s, Frisch became more aware of political issues. His relationship with Käte Rubensohn helped him see things more clearly. Even though their romance ended in 1939, it shaped his views.

Architecture Work

Frisch's second novel, An Answer from the Silence, was published in 1937. He quickly disliked this book. He even burned the original manuscript. He didn't want it included in later collections of his work. He even removed "author" from his passport.

In 1936, with help from his friend Werner Coninx, he studied architecture at ETH Zurich. This was his father's job. Even though he disliked his second novel, it won him the Conrad Ferdinand Meyer Prize in 1938. This prize came with money, which helped him financially.

When World War II started in 1939, Frisch joined the Swiss army. Switzerland was neutral, but the army prepared for a possible German invasion. By 1945, Frisch had served 650 days. He also started writing again. In 1940, his writings were put into a book called Pages from the Bread-bag. This book was generally positive about Swiss army life. However, Frisch later changed his mind. In 1974, he felt Switzerland had been too willing to cooperate with Nazi Germany during the war.

After getting his architecture degree in 1940, Frisch worked for William Dunkel. He could finally afford his own home. In 1942, he married Gertrud Frisch-von Meyenburg. They had three children: Ursula, Hans Peter, and Charlotte.

In 1943, Frisch won a competition to design a new swimming pool in Zürich. It was later named Max-Frisch-Bad. This big project allowed him to open his own architecture studio. The pool was built in 1947 and opened in 1949. It is now a protected historic building.

Frisch designed more than a dozen buildings. But only two were actually built. One was for his brother, and another for a shampoo maker. The shampoo maker's house led to a court case. Frisch later used this experience to create a character in his play The Fire Raisers. Even with his architecture studio, Frisch spent most of his time writing. In 1955, he closed his architecture business to become a full-time writer.

Theatre Work

Frisch often visited the Zürich Playhouse. This theatre was very lively at the time. Many talented actors and writers from Germany and Austria were living in exile there. In 1944, the theatre director, Kurt Hirschfeld, encouraged Frisch to write for the stage.

His first play, Santa Cruz, was written in 1944. It was first performed in 1946. In this play, Frisch explored how a person's dreams fit with married life. He had just gotten married himself. His 1944 novel, J'adore ce qui me brûle, also looked at this idea. It suggested that an artistic life might not fit well with a traditional middle-class life.

His next two plays were influenced by World War II. Now they sing again (1945) asked about the guilt of soldiers who follow cruel orders. It showed different viewpoints without simple answers. This play was performed in Zürich and Germany. However, the NZZ newspaper criticized it. They said it made the horrors of Nazism seem less bad.

The Chinese Wall (1946) explored the idea that humanity could be destroyed by the atomic bomb. This play started public discussions.

Working with director Kurt Hirschfeld, Frisch met other important playwrights. He met Carl Zuckmayer in 1946 and Friedrich Dürrenmatt in 1947. Dürrenmatt and Frisch became lifelong friends. In 1947, Frisch also met Bertolt Brecht, a famous German playwright. Frisch admired Brecht's work. They often talked about writing. Brecht encouraged Frisch to write more plays about social responsibility. Frisch respected Brecht but kept his own independent ideas. He became more doubtful of strong political views during the early cold war years. This is clear in his 1948 play As the war ended. It was based on stories about the Red Army as an occupying force.

Success as a Novelist

By 1947, Frisch had filled about 130 notebooks. These were published as Tagebuch mit Marion (Diary with Marion). It was more like essays and a literary autobiography than a daily diary. His publisher, Peter Suhrkamp, encouraged him to develop this style. In 1950, Suhrkamp's new publishing house released a second volume. This was Tagebuch 1946–1949. It was a mix of travel stories, personal thoughts, and essays. Critics liked how Frisch was creating a new kind of "literary diary." These books became more popular after his novels made him well-known.

In 1951, Frisch received a travel grant. He visited the United States and Mexico. During this time, he started working on his novel, I'm Not Stiller. Similar ideas were also in his play Don Juan or the Love of Geometry (1953). This play explored the conflict between marriage duties and intellectual interests. The main character, Don Juan, prefers studying geometry and playing chess over women. This play was very popular. It has been performed over a thousand times. It is Frisch's third most popular play.

The novel I'm Not Stiller came out in 1954. The main character, Anatol Ludwig Stiller, pretends to be someone else. But in court, he has to admit his real identity. He then goes back to live with his wife, whom he had left. The novel mixes detective story elements with a diary-like style. It was a big success and made Frisch a recognized novelist. Critics praised its structure and how it combined deep ideas with personal experiences. It also showed the difficulty of balancing art and family life. After this book, Frisch left his family. He moved to Männedorf and lived in a small apartment. Writing became his main job. In 1955, he officially became a full-time writer.

In 1955, Frisch started writing Homo Faber, published in 1957. It's about an engineer who sees life in a very logical, "technical" way. Homo Faber became a popular book for schools. It was Frisch's best-selling novel. The book includes a journey that was similar to Frisch's own trips to Italy, America, Mexico, and Cuba. The next year, Frisch visited Greece, which is where the end of Homo Faber takes place.

As a Playwright

The success of The Fire Raisers made Frisch a world-famous playwright. This play is about a middle-class man who lets homeless people stay in his house. Despite clear warnings, he doesn't realize they are going to burn his house down. Early ideas for this play came from 1948. They were published in his Tagebuch 1946–1949. A radio play version was broadcast in 1953. Frisch wanted the play to make the audience think. He wanted them to question if they would react wisely to danger. Swiss audiences saw it as a warning against Communism. Frisch felt misunderstood. For a performance in West Germany, he added a part warning against Nazism, but this was later removed.

Ideas for Frisch's next play, Andorra, also appeared in his Tagebuch 1946–1949. Andorra is about how people's ideas about others can be very powerful. The main character, Andri, is believed to be Jewish. His father, the Teacher, supposedly rescued him from "Blackshirts." Because of this, Andri faces unfair treatment. He develops traits that people see as "typically Jewish." The play also shows the hidden problems in the small fictional country. Later, it turns out Andri is his father's real son and not Jewish. But the townspeople are too stuck in their beliefs to accept this. Frisch wrote five versions of this play before it was first performed in 1961. It was a success with critics and audiences. However, it caused some debate, especially in the United States. Some felt it made the serious topic of the Holocaust seem too light.

In 1958, Frisch met the writer Ingeborg Bachmann. They started a relationship. He had left his wife and children in 1954 and divorced in 1959. Bachmann did not want to marry. But Frisch followed her to Rome, where she lived. Rome became important for both of them until 1965. Their relationship was very intense. Frisch's 1964 novel Gantenbein and Bachmann's novel Malina both show their feelings about this relationship. It ended in 1962–63. Gantenbein explores the end of a marriage through many "what if?" scenarios. Frisch wrote that his goal was to show a person's reality by showing them through many fictional versions of themselves.

His next play, Biography: A game (1967), followed naturally. Frisch was disappointed that his successful plays Biedermann und die Brandstifter and Andorra were misunderstood. He wanted to move away from plays that were like simple stories with a moral. He tried a new style called "Dramaturgy of Permutation". He started this with Gantenbein and continued it with Biography. The play is about a scientist who gets to live his life again. But he finds he can't make different choices the second time. The play's first performance in Zürich was delayed. When it finally opened, it didn't impress critics or audiences. Frisch felt he had expected too much from the audience. After this, he didn't write for the theatre for another eleven years.

Second Marriage and Living Abroad

In 1962, Frisch met Marianne Oellers, a student. He was 51, and she was 28 years younger. In 1964, they moved to Rome. In 1965, they moved to a renovated cottage in Berzona, Ticino, Switzerland. For the next ten years, they often lived in rented homes abroad. Frisch sometimes spoke negatively about Switzerland. But they always kept their Berzona home and returned to it often. Frisch loved driving his car to this peaceful place.

In 1966, they also tried living in a city apartment in Aussersihl, Zürich. This area was known for crime. But they quickly moved to an apartment in Küsnacht, near Lake Zurich. Frisch and Oellers married at the end of 1968.

Oellers traveled with Frisch on many trips. In 1963, they visited the United States for the premieres of his plays. In 1965, they went to Jerusalem, where Frisch received the Jerusalem Prize. To learn about life behind the Iron Curtain, they toured the Soviet Union in 1966. They returned in 1968 for a Writers' Congress. There they met Christa Wolf, a leading author from East Germany. They became good friends. After they married, they continued to travel, visiting Japan and staying in the United States. Many of his thoughts from these trips are in his Tagebuch (1966–1971).

In 1972, they moved to West Berlin. Frisch became more involved in the city's intellectual life. Living away from Switzerland made him feel even more critical of his home country. He showed this in his writings, like "William Tell for Schools" (1970) and Little service book (1974). In 1974, he gave a speech called "Switzerland as a homeland?" when accepting the Grand Schiller Prize. Frisch was interested in social democratic politics. He became friends with Helmut Schmidt, who was then the Chancellor of Germany. In 1975, Frisch went with Chancellor Schmidt on a trip to China. In 1977, Frisch gave a speech at a political party conference.

In 1974, Frisch started a relationship with an American woman. This happened in Montauk, New York. He wrote an autobiographical novel called Montauk (1975) about his love life. This led to a public disagreement between Frisch and his wife. They divorced in 1979.

Later Life and Passing

In 1978, Frisch had serious health problems. The next year, he helped create the Max Frisch Foundation. This foundation manages his writings and other works. The foundation's archive is at the ETH Zurich and opened to the public in 1983.

As he got older, Frisch's work often focused on aging and how life changes. In 1976, he started writing the play Triptychon. It was ready to be performed three years later. The play has three parts, like a painting. Many characters in it are already dead. It was first a radio play in 1979 and then performed on stage.

In 1980, Frisch reconnected with Alice Locke-Carey. They lived together in New York City and his cottage in Berzona until 1984. Frisch became a respected writer in the United States. He received honorary degrees from Bard College in 1980 and City University of New York in 1982. His novella Man in the Holocene (1979) was praised by critics. It's about an older man whose mind is declining. Frisch wrote it with real feeling from his own experience of getting older. After Man in the Holocene, Frisch had trouble writing. This ended with his last major work, the novella Bluebeard, in 1981.

In 1984, Frisch moved back to Zürich. He lived there for the rest of his life. In 1983, he started a relationship with Karen Pilliod. In 1987, they visited Moscow for a "Forum for a world liberated from atomic weapons." In March 1989, Frisch was diagnosed with cancer. In the same year, it was found that Swiss security services had been illegally watching Frisch since 1948.

Frisch planned his own funeral. He also discussed getting rid of the Swiss army. He published a dialogue about it called Switzerland without an Army? A Palaver. Max Frisch passed away on April 4, 1991, just before his 80th birthday. His funeral was held in Zürich. His friends spoke at the ceremony. Frisch was an agnostic, meaning he didn't believe in organized religion. His ashes were later scattered by his friends in Ticino. A tablet in the cemetery at Berzona remembers him.

Max Frisch and Film

The film director Alexander J. Seiler believed Frisch had a difficult relationship with movies. Even though Frisch's writing style was often like a film. Frisch often tried to show the "white space" between words, which is easier to do in film.

In his Diary 1946–1949, there was an early idea for a film script. His first real experience with film was in 1959. But he left a film project called SOS Glacier Pilot. In 1960, his script for William Tell was rejected. The film was made anyway, but not how Frisch wanted it. In 1965, there were plans to film a part of his novel Gantenbein. This project was called Zürich – Transit. But it was stopped because of disagreements and illness. The film was finally made in 1992, a year after Frisch died.

There were many ideas to make films of his novels I'm Not Stiller and Homo Faber. But none of these happened. However, several of Frisch's plays were made into TV adaptations. The first film based on Frisch's prose was The Misfortune in 1975. It was based on a sketch from his diaries. Later, TV productions were made of Montauk (1981) and Bluebeard.

A full cinema version of Homo Faber was finally made a few months after Frisch died. Frisch had worked with the filmmaker Volker Schlöndorff on it. But critics were not very impressed. In 1992, a film called Holozän was made from Man in the Holocene. It won a special award at the Locarno International Film Festival.

Awards and Honors for Max Frisch

- 1935: Prize for a single work for Jürg Reinhart from the Swiss Schiller Foundation

- 1938: Conrad Ferdinand Meyer Prize (Zürich)

- 1940: Prize for a single work for "Pages from the Bread-bag" ("Blätter aus dem Brotsack") from the Swiss Schiller Foundation

- 1942: First (out of 65 entrants) in an architecture contest (Zürich: Freibad Letzigraben)

- 1945: Welti Foundation Drama prize for Santa Cruz

- 1954: Wilhelm Raabe prize (Braunschweig) for Stiller

- 1955: Prize for all works to date from the Swiss Schiller Foundation

- 1955: Schleußner Schueller prize from Hessischer Rundfunk (Hessian Broadcasting Corporation)

- 1958: Georg Büchner Prize

- 1958: Charles Veillon Prize (Lausanne) for Stiller and Homo Faber

- 1958: Literature Prize of the City of Zürich

- 1962: Honorary doctorate from the Philipp University of Marburg

- 1962: Major art prize of the City of Düsseldorf

- 1965: Jerusalem Prize for the Freedom of the Individual in Society

- 1965: Schiller Memorial Prize (Baden-Württemberg)

- 1973: Major Schiller Prize from the Swiss Schiller Foundation

- 1976: PFriedenspreis des Deutschen Buchhandels

- 1979: Gift of honour from the "Literaturkredit" of the Canton of Zürich (rejected!)

- 1980: Honorary doctorate from Bard College (New York state)

- 1982: Honorary doctorate from the City University of New York

- 1984: Honorary doctorate from the University of Birmingham

- 1984: Nominated a Commander, Ordre des Arts et des Lettres (France)

- 1986: Neustadt International Prize for Literature from the University of Oklahoma

- 1987: Honorary doctorate from the Technical University of Berlin

- 1989: Heinrich Heine Prize (Düsseldorf)

Max Frisch received honorary degrees from several universities. These included the University of Marburg in Germany (1962), Bard College in New York (1980), and the City University of New York (1982).

He also won many important German literature awards. These were the Georg Büchner Prize in 1958, the Peace Prize of the German Book Trade in 1976, and the Heinrich Heine Prize in 1989. In 1965, he won the Jerusalem Prize for individual freedom in society.

The City of Zürich created the Max Frisch Prize in 1998 to remember him. This prize is given every four years.

In 2011, there was an exhibition in Zürich to celebrate 100 years since Frisch's birth. Other exhibitions were held in Munich and Loco, near his cottage in Ticino. In 2015, a new city square in Zürich was named Max-Frisch-Platz.

Major Works by Max Frisch

Novels

- Antwort aus der Stille (1937, An Answer from the Silence)

- Stiller (1954, I'm Not Stiller)

- Homo Faber (1957)

- Mein Name sei Gantenbein (1964, A Wilderness of Mirrors)

- Dienstbüchlein (1974)

- Montauk (1975)

- Der Mensch erscheint im Holozän (1979, Man in the Holocene)

- Blaubart (1982, Bluebeard)

- Wilhelm Tell für die Schule (1971, William Tell: A School Text)

Plays

- Nun singen sie wieder (1945)

- Santa Cruz (1947)

- Die Chinesische Mauer (1947, The Chinese Wall)

- Als der Krieg zu Ende war (1949, When the War Was Over)

- Graf Öderland (1951)

- Biedermann und die Brandstifter (1953, translated as The Firebugs or The Fire Raisers)

- Don Juan oder Die Liebe zur Geometrie (1953)

- Die Grosse Wut des Philipp Hotz (1956)

- Andorra (1961)

- Biografie (1967)

- ‘‘Die Chinesische Mauer (Version für Paris)‘‘ (1972)

- Triptychon. Drei szenische Bilder (1978, Triptych)

- Jonas und sein Veteran (1989)

Images for kids

-

Bertolt Brecht in 1934. Brecht influenced Frisch's early work.

See also

In Spanish: Max Frisch para niños

In Spanish: Max Frisch para niños

- Max Frisch Archive

| Precious Adams |

| Lauren Anderson |

| Janet Collins |