Mesoamerican architecture facts for kids

Mesoamerican architecture is the amazing building style created by ancient cultures in Mesoamerica. This area includes parts of modern-day Mexico and Central America. These buildings are mostly large, public structures used for ceremonies and city life.

The architecture has many different regional styles. But they are all connected because cultures shared ideas over thousands of years. Mesoamerican architecture is most famous for its huge pyramids. These are some of the biggest pyramids outside of Ancient Egypt.

One interesting idea is how their beliefs, religion, and geography influenced their buildings. Many features of Mesoamerican architecture were shaped by religious stories. For example, most cities were planned based on the cardinal directions (north, south, east, west). These directions had special meanings in their mythology.

Another important part of Mesoamerican architecture is its iconography. This means the buildings were decorated with images and symbols. These decorations often showed religious or cultural ideas. Sometimes, they even had writing from Mesoamerican writing systems. These images and texts help us learn a lot about ancient Mesoamerican society, history, and religion.

Contents

Time Periods of Mesoamerican Architecture

Mesoamerican history is divided into different time periods. Each period had its own important cultures, cities, and building styles. Here's a simple look at these times:

| Period | Time | Important Cultures, Cities, and Buildings |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-Classic (Formative) | 2000 BC – 200 AD | Olmec, Early Maya, Monte Albán, Pyramid of the Sun (early stages) |

| Early Pre-Classic | 2000 BC – 1000 BC | Olmec centers like San Lorenzo Tenochtitlan |

| Middle Pre-Classic | 1000 BC – 400 BC | Late Olmec, Early Maya, La Venta, El Mirador |

| Late Pre-Classic | 400 BC – 200 AD | Preclassic Maya, Teotihuacan, Uaxactún, Tikal |

| Classic | 200 AD – 900 AD | Classic Maya, Teotihuacan, Zapotecs |

| Early Classic | 200 AD – 600 AD | Teotihuacan at its peak, Palenque, Copán |

| Late Classic | 600 AD – 900 AD | Xochicalco, Uxmal, Puuc style, Rio Bec style |

| Post-Classic | 900 AD – 1519 AD | Maya Itzá, Chichen Itza, Toltec, Aztec |

| Early Post-Classic | 900 AD – 1200 AD | Cholula, Tula, El Tajín |

| Late Post-Classic | 1200 AD – 1519 AD | Aztec Empire, Tenochtitlan, Templo Mayor |

City Planning and Beliefs

How Cities Copied the Cosmos

Symbolism in City Layout

Ancient Mesoamericans believed their cities should be a small copy of the universe. They thought the world was divided into an underworld and a human world. This idea was shown in how their cities were built.

The northern part of a city often represented the underworld. You might find tombs or buildings linked to death there. The southern part stood for life and new beginnings. This area often had homes, markets, and monuments about important families.

Between these two halves was the main plaza. This open space often had tall stone monuments called stelae. These stelae were like the "world tree," a central point connecting the different parts of the universe. A ballcourt was also often in the plaza. It was seen as a place where the human world and underworld could meet.

Some experts believe that pyramids were like mountains. Stelae were like trees. Wells and ballcourts were like caves that led to the underworld.

Building Orientation

Mesoamerican buildings were often built to line up with events in the sky. Some temples and pyramids were designed so that sunlight would hit them in a special way on certain important days.

A famous example is the "El Castillo" pyramid at Chichen Itza. Around the spring and fall equinoxes, a shadow that looks like a snake appears on its steps. This snake shape is linked to the god Quetzalcoatl.

Many buildings also faced about 15 degrees east of north. This alignment helped them track important dates for farming. It also helped them follow their sacred 260-day calendar. While most buildings faced the sun, some important ones, like the Governor's Palace at Uxmal, faced Venus.

The Plaza: City Center

Almost every ancient Mesoamerican city had one or more large public plazas. These were impressive open spaces surrounded by tall pyramids, temples, and other important buildings. People used these plazas for many things. They held religious ceremonies, markets, big public events, and celebrations.

The size of these main plazas varied a lot. The biggest was in Tenochtitlan, covering about 115,000 square meters. This was huge because Tenochtitlan was a very large city. Most plazas were around 3,000 square meters. Some cities had many smaller plazas, while others focused on one very large main plaza.

Tenochtitlan: A Great City

Tenochtitlan was a powerful Aztec city that existed from 1325 to 1521. It was built on an island in Lake Texcoco. The city had a complex system of canals, bridges, and waterways. This allowed it to provide for its many people. The island was about 12 square kilometers and had around 125,000 residents. This made it the largest Mesoamerican city ever recorded.

The main plaza of Tenochtitlan was enormous. The city's main temple, called Templo Mayor (Great Temple), was 100 meters by 80 meters at its base and 60 meters tall. The city was eventually destroyed by the Spanish in 1521.

Archaeologists found that the Aztecs rebuilt and enlarged the Templo Mayor seven times. But they always kept its main design. This design honored two gods: Tlaloc, the rain god, and Huitzilopochtli, the god of war.

Pyramids: Reaching for the Sky

Often, the most important religious temples were built on top of tall pyramids. This was probably because they wanted to be as close to the heavens as possible. While some pyramids were used as tombs, the temples on top usually did not contain burials.

These temples, sitting on pyramids sometimes over two hundred feet tall, were very impressive. They often had a "roof comb," which was a tall, decorative wall on top. These grand temples might have also served as a way to show the power of the rulers.

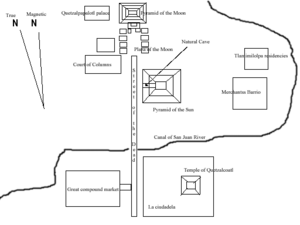

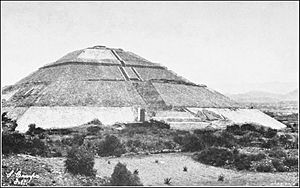

Pyramid of the Sun

The Pyramid of the Sun is the biggest building in the city of Teotihuacan. It is also one of the largest structures in the entire Western Hemisphere. It stands about 216 feet (66 meters) tall. Its base is roughly 720 by 760 feet (220 by 230 meters).

The pyramid is on the east side of the "Avenue of the Dead." This avenue runs almost directly through the center of Teotihuacan. Archaeologists found animal remains, masks, and figures inside the pyramid. This suggests it was likely used as a ritual temple.

Temple of the Feathered Serpent

The Temple of the Feathered Serpent was built after the Pyramid of the Sun and the Pyramid of the Moon. This temple shows one of the first uses of the "talud-tablero" architectural style.

The temple's surfaces had colorful murals. Its decorative panels, called tableros, featured large serpent heads with fancy headdresses. The feathered serpent refers to the Aztec god Quetzalcoatl.

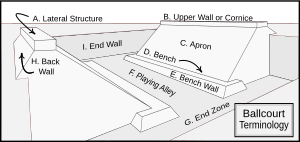

Ballcourts: Sacred Games

The Mesoamerican ballgame was a very important ritual. It was seen as a symbolic journey between the underworld and the world of the living. Many ball courts are found in the middle of cities. They acted as a link between the northern and southern parts of the city.

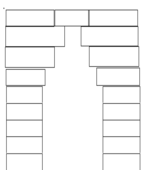

Most ball courts were made of stone. Over 1,300 ball courts have been found. While their sizes vary, they all have a similar shape. They have a long, narrow playing area flanked by two walls. These walls had horizontal, sloped, and sometimes vertical surfaces. Later vertical walls, like those at Chichen Itza, were often covered with detailed carvings. These carvings sometimes showed scenes of human sacrifice.

Early ball courts had open ends. But later ones had enclosed end-zones. This gave the structure an "I" shape when viewed from above. The playing area could be at ground level or "sunken."

Building ball courts was a big challenge. For example, one stone on El Tajin's South Ball court is 11 meters long and weighs over 10 tons!

Homes for the Elite

Large and often beautifully decorated, palaces were usually near the city center. They housed the most important people, the elite. A very large royal palace, or one with many rooms on different levels, might be called an acropolis.

However, many palaces were one-story buildings. They had many small rooms and usually at least one inner courtyard. These buildings were designed to be functional homes. They also had decorations to show the high status of the people living there.

Archaeologists believe that many palaces also contained tombs. At Copán, a tomb for an ancient ruler was found beneath layers of later building. The North Acropolis at Tikal also seems to have been a burial site for many people during earlier periods.

Building Materials and Methods

One surprising thing about these great Mesoamerican buildings is that they were built without many advanced tools. They didn't have metal tools. This meant that Mesoamerican architecture needed one thing in huge amounts: human labor.

But other materials were easy to find. They often used limestone. This stone was soft enough to be shaped with stone tools when it was first dug up. It only became hard after it was removed from the ground. They also used crushed, burned, and mixed limestone for mortar. This was like cement and was used for stucco finishes as well. Later, they got better at cutting stones, so they fit together perfectly. But stucco was still important for some roofs.

In central Mexico, a light volcanic rock called tezontle was common. Palaces and large buildings were often made of this rough stone. Then, they were covered with stucco or a thin layer of fine stone called cantera. Very large and fancy decorations were made from a strong stucco, especially in the Maya region. They even used a type of concrete.

For common houses, people used wood frames, adobe (mud bricks), and thatch roofs over stone foundations. But some stone houses for common people have also been found. Buildings usually had high, slanted roofs, often made of wood or thatch. Stone roofs with high slants were also used, but less often.

Architectural Styles

Megalithic Style

This building style used large, dry-laid limestone blocks. These blocks were about 1 meter by 50 cm by 30 cm. They were then covered with a thick layer of stucco. This style was common in the northern Maya lowlands from the early to middle periods.

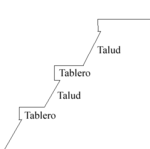

Talud-tablero Style

Pyramids in Mesoamerica were built in platforms. Many used a style called talud-tablero. This style first became popular in Teotihuacan. It has a sloped lower part (the "talud") with a flat, vertical panel (the "tablero") on top. Many different versions of this style appeared across Mesoamerica.

Classic Maya Styles

Famous Maya cities like Palenque, Tikal, Copán, and Toniná show unique Classic Period Maya styles. They often used a special type of arch called the corbelled arch.

"Toltec" Style

This style is seen in places like Chichen Itza and Tula Hidalgo. It features specific sculptures like chacmools (reclining figures) and Atlantean figures (statues of warriors holding up roofs). Designs related to the god Quetzalcoatl are also common.

Puuc Style

The Puuc style is named after the Puuc hills where it developed. It was popular in the northern Maya lowlands during the later Classic period. Puuc architecture uses thin stone coverings over a concrete core.

Buildings typically had two main parts on their front. The lower part was plain with flat cut stones and doorways. The upper part was richly decorated. It had repeating geometric patterns and symbols. The distinctive curved-nosed masks of the god Chaac are a common feature. Carved small columns are also often seen.

Building Technology

Corbelled Arch

Mesoamerican cultures never invented the keystone, which is a central wedge-shaped stone that locks an arch in place. So, they couldn't build "true" arches. Instead, they used a "false" or corbelled arch.

These arches are built by stacking stones so that each layer sticks out a little further than the one below it. Eventually, the two sides meet at the top. This type of arch supports less weight than a true arch.

Some experts suggest that the Mesoamerican "arch" was actually a different system. They say it used cast concrete and timber beams. This system might have been stronger than a simple corbelled arch.

True Arch Discoveries

Some scholars believe that true arches were known in Mesoamerica before Europeans arrived. They point to examples at Maya sites like La Muneca and Nukum. Also, two low domes at Tajin and a sweat bath at Chichen Itza might show true arches.

In 2010, a robot found a long, arch-roofed passageway under the Pyramid of Quetzalcoatl in Teotihuacan. This passage dates back to around 200 AD.

UNESCO World Heritage Sites

Many important archaeological sites with Mesoamerican architecture are recognized as "World Heritage Sites" by UNESCO.

El Salvador

- Maya site of Joya de Cerén

Honduras

- Maya Site of Copán

Guatemala

Mexico

- Pre-Hispanic City and National Park of Palenque

- Pre-Hispanic Town of Uxmal

- Pre-Hispanic City of Teotihuacan

- Historic Centre of Oaxaca and Archaeological Site of Monte Albán

- Pre-Hispanic City of Chichen Itza

- Archaeological Monuments Zone of Xochicalco, Morelos

- El Tajin, Pre-Hispanic City of Veracruz

- Ancient Maya City of Calakmul, Campeche

- Historic Centre of Mexico City and Xochimilco (with Templo Mayor and nearby temples)

- Agave Landscape and Ancient Industrial Facilities of Tequila (with Guachimontones and near teuchitlán culture sites)

- Prehistoric Caves of Yagul and Mitla in the Central Valley of Oaxaca (with the Yagul archaeological site)

See also

In Spanish: Arquitectura mesoamericana para niños

In Spanish: Arquitectura mesoamericana para niños

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |