Portrait miniature facts for kids

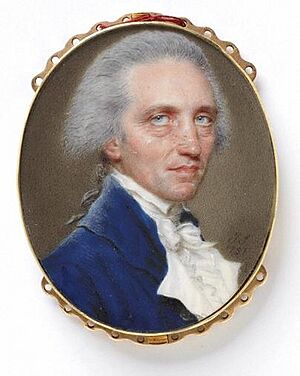

A portrait miniature is a very small portrait painting. Artists usually made them using gouache, watercolor, or enamel. These tiny artworks grew out of the techniques used for painting in illuminated manuscripts (decorated books).

Portrait miniatures became popular among rich people in the 1500s, especially in England and France. Their popularity spread across Europe from the mid-1700s. They stayed very popular until daguerreotypes and photography came along in the mid-1800s.

People often gave these miniatures as personal gifts within families. Sometimes, young men gave them to women they hoped to marry. Rulers, like James I of England, also gave them as gifts to other countries or for political reasons. Miniatures were especially popular when a family member was going to be away for a long time. This could be a husband or son going to war or moving away, or a daughter getting married.

The first artists who made miniatures used watercolor paint on thin vellum (treated animal skin). In England, they sometimes painted on playing cards cut into the right shape. This art was often called limning. Later, in the second half of the 1600s, painting with enamel on copper became popular, especially in France. In the 1700s, artists started using watercolor on ivory, which was cheaper by then.

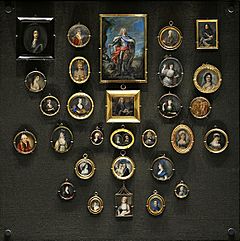

These tiny portraits could be as small as 40 mm × 30 mm (about 1.5 x 1.2 inches). People often put them into lockets, inside watch covers, or as part of jewelry. This way, they could carry them around. Others were put in frames to stand on a table or hang on a wall. Some even decorated the lids of snuff boxes.

Contents

The Start of Portrait Miniatures

Portrait miniatures grew from illuminated manuscripts. These were handwritten books with beautiful drawings and decorations. Over time, new ways of illustrating books, like woodprints, became more common. This meant manuscript painters started looking for new ways to use their skills.

The first artists to paint portrait miniatures were famous manuscript painters. One was Jean Fouquet, who painted a self-portrait in 1450. This might be the very first portrait miniature and possibly the first formal self-portrait. Another was Simon Bening. His daughter, Levina Teerlinc, mostly painted portrait miniatures. She moved to England, where Hans Holbein the Younger also painted some miniatures as a court artist. Lucas Horenbout was another artist from the Netherlands who painted miniatures for King Henry VIII.

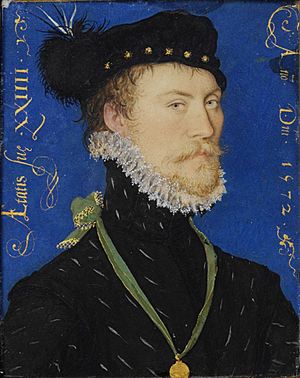

France also had a strong tradition of miniatures, especially at the royal court. Early French miniature painters included Jean Clouet and his son François Clouet.

The first famous English portrait miniaturist was Nicholas Hilliard (around 1537–1619). His work was very detailed and showed the person's character well. He used strong colors and gold to make his paintings shine. He painted on card. Hilliard worked in France for a while. His son, Lawrence Hilliard, followed him. Lawrence's work was similar but bolder and richer in color.

Isaac Oliver (around 1560–1617) and his son Peter Oliver (1594–1647) came after Hilliard. Isaac was Hilliard's student, and Peter was Isaac's student. They were the first to make the faces in their paintings look more rounded and lifelike. They painted very small miniatures, but also larger ones up to 10 by 9 inches (250 mm × 230 mm). They even copied famous paintings by old masters for Charles I of England.

John Hoskins (died 1664) was followed by his son, also named John.

Samuel Cooper (1609–1672) was a nephew and student of the elder Hoskins. Many people consider him the greatest English portrait miniaturist. He spent time in Paris and Holland. His work is known for its strength and dignity. He painted on card, chicken skin, vellum, and even thin pieces of mutton bone. Ivory was not used until much later. His work often has his initials, usually in gold, and the date.

Other artists from this time included Alexander Cooper and David des Granges. Later artists like Gervase Spencer and Nathaniel Hone helped start the Royal Academy. Artists who drew with black lead, called plumbago, like David Loggan, also created very detailed works.

In 1733, many portrait miniatures were destroyed in a fire at White's Chocolate and Coffee House. A large collection of miniatures by Hilliard, the Olivers, and Samuel Cooper burned. The ashes were even sifted to find gold from the melted frames.

Popularity Across Countries

Denmark

In Denmark, Cornelius Høyer was a specialist in miniature painting in the late 1700s. He was named the Miniature Painter to the Danish Court in 1769. He also worked for royal families in other European countries and became very famous. Christian Horneman followed him as Denmark's top miniature artist. One of his most famous works is a portrait of Ludwig van Beethoven from 1802. Beethoven liked it a lot, perhaps because it made him look more handsome!

England

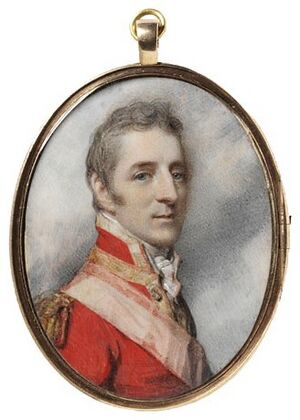

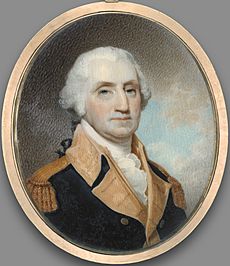

The 1700s saw many miniature painters in England. Richard Cosway (1742–1821) is the most famous. His works are beautiful and painted with a special energy that no other artist matched. He mostly painted on ivory. His best miniatures are signed on the back.

George Engleheart (1750–1829) painted 4,900 miniatures. He often signed his work with "E" or "G.E." Andrew Plimer (1763–1837) was Cosway's student. Both he and his brother Nathaniel Plimer created lovely portraits. John Smart (around 1740–1811) was also a very important miniaturist of the 1700s. His work was praised for being refined and delicate.

Colonial India Portrait miniatures were also important for British people in Colonial India. Young soldiers sent to India often hoped to gain status, get promotions, and prepare for marriage when they returned home. However, the hot climate in India was harsh on their skin. British society often judged these physical changes harshly.

Young men would have their portraits painted when they arrived in India. They sent these back to their mothers, sisters, and future wives to show they were healthy and safe. Many of these miniatures were painted by British artists who were temporarily in India. John Smart, for example, spent 1785-1795 in Madras and was very popular with British soldiers.

Miniatures from Colonial India painted on ivory were different from those on canvas with oil. They were more expensive to commission. Also, they were fragile and risky to pack and ship. Shipping ivory miniatures often cost more because of the higher chance of damage or loss. These miniatures show new art methods and the cultural history of the portrait miniature in Colonial India.

Scotland

Andrew Robertson (1777–1845) and his brothers Alexander and Archibald created a new style. Their portrait miniatures were slightly larger, about 9 by 7 inches (23 x 18 cm). Robertson's style became very popular in Britain by the mid-1800s.

Ireland

Gustavus Hamilton (1739–1775) learned art at the National College of Art and Design in Dublin. He became a miniature painter and was very successful. Many important ladies hired him. He showed his miniatures at the Society of Artists in Dublin from 1765 to 1773.

France

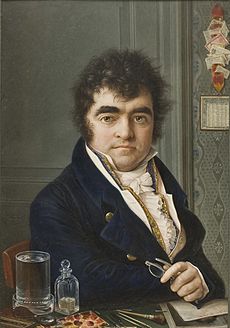

In the 1700s, famous artists like Nicolas de Largillière and François Boucher painted miniatures. But the most important artists working in France were Peter Adolf Hall from Sweden, François Dumont from France, and Friedrich Heinrich Füger from Austria.

The most popular artists in France were Jean-Baptiste Jacques Augustin (1759–1832) and Jean-Baptiste Isabey (1767–1855). Their portraits of Napoleon and his court are very fine. Augustin was perhaps the best French miniature painter.

Spain

Portrait miniatures were used in the Spanish court starting in the late 1400s. This began with a political agreement between Henry VII of England and Ferdinand of Aragon. They celebrated the marriage promise between Catherine of Aragon and Prince Arthur of England in 1489. They exchanged gifts, including jewels and portrait miniatures of the young couple.

Soon after, the idea of using portrait miniatures to celebrate marriage promises became popular in both courts, especially in Spain. These miniature tokens were seen as very personal gifts for the engaged couple and their families. In Spain and England, miniatures were often decorated with jewels or kept in fancy lockets. People could hide them or take them out to admire them whenever they wished.

The Spanish painter Francisco Goya (1746–1828) painted portrait miniatures for mourning and weddings starting in 1806. Goya mostly used oil paint, but he also took orders for pencil miniatures. Between 1824 and 1825, Goya recorded painting over 40 miniatures on ivory. While most artists dabbed color onto the ivory, Goya used water to shape the lines of his miniatures. He thought his shaping technique was new and different.

United States

The English style of portrait miniatures also came to the American colonies. One of the first American miniaturists was Mary Roberts (died 1761), the first American woman to work in this art form. In the late 1700s, Mary Way and her sister Betsey created "dressed miniatures." These had real fabric, ribbons, and lace attached to the images.

Amalia Küssner Coudert (1863–1932) from Indiana was known for her portraits of rich New Yorkers and European royalty in the late 1800s. She painted watercolor portraits on ivory for people like Caroline Astor, King Edward VII, Czar Nicholas II of Russia, and Cecil Rhodes. Robert Field was one of the most famous miniature painters in America during the 1700s.

Many important miniatures were made by women artists. For example, Eda Nemoede Casterton showed her work in the famous Paris Salon. She used thin sheets of ivory for her paintings, which was common for miniature portraitists. Around 1900, there was a new interest in miniature portraits in the United States. This led to the creation of the American Society of Miniature Painters in 1899. Artists like Virginia Richmond Reynolds and Lucy May Stanton became very successful.

Portrait Miniatures and Mourning in Colonial America Throughout history, people have carried portraits to remember loved ones who have passed away. This practice came to Colonial America in the mid-1700s. Portrait miniatures honoring the dead could be rings, brooches, lockets, or small framed pictures.

Before miniatures, people often received rings or lockets with words or images matching those in the coffin. These matching items created a special connection, helping grieving families feel closer to their loved one. In the 1700s, the focus shifted from mourning death to celebrating life. This changed the meaning of these tokens. They no longer just represented sadness but also hope and remembrance.

The first miniature portraits in Colonial America appeared in the 1750s. These portraits were usually ordered to remember someone who died suddenly and young. For example, the family of a twelve-year-old girl named Hannah had a locket made. It showed her as she looked before she got sick. The locket had angel wings above her and the words "NOT LOST" on the side. Such portraits brought hope and remembrance instead of constant sorrow.

Materials and Techniques

The earliest miniatures were painted on vellum (treated animal skin), chicken-skin, or cardboard. Artists like Hilliard also used the backs of playing cards or very thin vellum glued onto playing cards. Vellum was seen as an easier choice than copper in the 1600s.

During the 1700s, watercolor on ivory became the main material. Ivory started being used around 1700.

Enamel: Portrait miniatures painted on enamel with a copper base were first made in Italy in the 1500s. Artists in Germany, Portugal, and Spain also used this method in the 1600s, 1700s, and 1800s. Many Dutch and German artists used copper, which made the images even better. Over time, only very rich people could afford copper. This made artists use stretched vellum, ivory, or paper instead.

Jean Petitot (1607–1691) was the greatest artist using enamel. He painted his best portraits in Paris for Louis XIV of France. His son followed in his footsteps. Other enamel artists included Christian Friedrich Zincke and Johann Melchior Dinglinger. Many of these artists were French or Swiss, but most visited and worked in England for a while. The greatest English enamel portrait painter was Henry Bone (1755–1839). Enamel remained a strong choice for portrait miniatures throughout the 1700s and 1800s.

Mica: Mica is a very thin, clear mineral. It could be painted with oil and placed over a portrait miniature. This allowed the owner to "dress up" the person in the portrait or hide their identity.

Costume Overlays

Costume overlays were a technique where artists painted a person in a costume or different clothes to hide who they were. Usually, the portrait was made with a thin, removable overlay of mica. Hiding the identity of a miniature was important if the person was an unpopular ruler. Carrying their picture could cause trouble.

One example is painting over a portrait with a costume to hide the original. The Los Angeles County Museum of Art found a series of portrait miniatures from England from the 1650s. They seemed to show the same woman in different dresses. This woman looked a lot like the English king Charles I (1600–1649), who was executed in 1649. The king remained popular with some people after his death. Many found subtle ways to honor him. This discovery shows how portrait miniatures could also be a way to remember loss and show loyalty.

Where to See Them

Many museums display original portrait miniatures. These include the Museum of Arts in Boston and the Astolat Dollhouse Castle when it is on public display. The National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C., and the Victoria and Albert Museum in London have many portrait miniatures in their larger collections. Many of these can also be seen online.

Exhibitions

- International Biennial of Miniature Art (since 1989), Gornji Milanovac, Serbia

- International Biennial of Miniature Art (since 2000), Częstochowa, Poland

- Annual Royal Miniature Society Exhibition, London, UK

|

See also

In Spanish: Retrato en miniatura para niños

In Spanish: Retrato en miniatura para niños