New York Hall of Science facts for kids

|

|

Entrance with the original building in the background (2019)

|

|

| Established | 1964 |

|---|---|

| Location | 47-01 111th Street Corona, New York |

| Type | Science-technology museum |

| Accreditation | ASTC |

| Public transit access | Subway: Bus: Q23, Q58 at 108th Street, Q14 at 104th Street |

| Nearest car park | On-site |

The New York Hall of Science, also known as NYSCI, is a cool science museum located in Flushing Meadows–Corona Park in the Corona neighborhood of Queens, New York City. It's one of the few buildings left from the 1964 New York World's Fair. The museum has over 400 hands-on exhibits that teach you about biology, chemistry, and physics.

The original building, called the Great Hall, was designed by Wallace Harrison. It's an 80-foot-high (24 m) curving concrete structure. Over the years, the museum has added new parts, including a glass-and-metal north wing, a science playground, and Rocket Park, which has real spacecraft!

The Hall of Science first opened as an attraction for the 1964 World's Fair. It became a permanent museum in 1966. After some tough times and renovations in the 1970s and 1980s, it reopened in 1986 under the leadership of Alan J. Friedman. He helped the museum grow a lot, adding new sections. The original building was also updated between 2009 and 2015. The museum temporarily closed during the early 2020s because of the COVID-19 pandemic and Hurricane Ida, but it has since reopened and continues to welcome visitors.

NYSCI is mostly focused on teaching kids about science. It has many permanent exhibits and also hosts special traveling shows. The museum offers programs for students, runs the Alan J. Friedman Center for youth education, and hosts fun events like the seasonal Queens Night Market and Maker Faire.

Contents

Museum History and Beginnings

The New York Hall of Science and its Rocket Park were first built for the 1964 New York World's Fair. Before this, New York City didn't have a museum just for science.

Planning the Museum

Early Ideas for a Science Center

In 1960, a U.S. Representative named Seymour Halpern suggested getting money to build a permanent science museum at the World's Fair. Robert Moses, who was in charge of the World's Fair, also wanted a big science museum in Flushing Meadows–Corona Park.

In 1962, New York City Council members started discussing plans for a $15–20 million science museum. Many people, including Mayor Robert F. Wagner Jr., supported building it at the World's Fair site. This location was near the Long Island Rail Road tracks in Corona.

Getting Approval and Funding

Another group, the New York Museum of Science and Technology, wanted to build their museum in Manhattan. They thought the World's Fair site was too far away. However, in April 1963, the Hall of Science at the World's Fair was approved by the city. New York Governor Nelson Rockefeller allowed the city to work with non-profit groups to run the museum.

Designing and Building the Hall

Wallace K. Harrison was chosen to design the museum. It was planned to have 32,000 square feet (3,000 m2) of exhibit space. The city first gave $3.6 million for the Hall of Science. Construction started on June 19, 1963. To build it faster, Harrison decided to make the concrete panels for the museum off-site, then bring them to the location. By October 1963, the project needed more money, and Mayor Wagner approved a $5.5 million contract.

At the same time, the World's Fair Corporation set aside 5.5 acres (2.2 ha) for a "space island" next to other big company pavilions. In March 1964, the U.S. government announced they would run the United States Space Park at the fair, showing off spacecraft loaned by NASA. The Hall of Science building was not fully ready when the fair opened on April 22, 1964. By mid-1964, the cost of the Hall of Science had grown to over $7.5 million.

World's Fair Operation

The Hall of Science's basement exhibits opened on June 16, 1964. The whole building was officially dedicated on September 9, 1964. It had 12 exhibits about science and health, often sponsored by companies. These included models of the brain, the human digestive system, and exhibits about cancer detection and ocean life. There was also a film called Rendezvous in Space, three space vehicles, and a children's exhibit called Atomsville USA.

When the Space Park opened, it featured three tall rockets, measuring 90 to 110 feet (27 to 34 m) high. It also had the Discoverer 14 satellite and models of other satellites and rockets. Visitors could see a lunar excursion module, Thor and Atlas rockets, and a space capsule from Project Mercury. Young hosts helped visitors learn about the Space Park. Because it was a bit hidden, the Space Park had about 6,000 to 7,000 visitors daily, which was less than other popular fair attractions.

The World's Fair ended its first season on October 18, 1964. The city government decided to keep the Hall of Science after the fair. The U.S. government also planned to give the Space Park to the museum. The fair's second season ran from April 21 to October 17, 1965. During this time, the Hall of Science hosted science demonstrations. The U.S. government added exhibits to the Space Park, like the spacecraft from the Gemini 4 mission. The museum needed at least $5 million to keep running after the fair, but this money wasn't raised, so the pavilion temporarily closed.

Becoming a Museum

Transforming into a Permanent Museum

In mid-1965, it was suggested that the Hall of Science should stay after the fair, even though most other fair buildings would be torn down. In December 1965, the City Council gave $67,000 to the museum. By early 1966, the Hall of Science was one of the few remaining structures from the World's Fair. The museum's leaders wanted to use other nearby buildings for more space, but those plans didn't happen.

The city spent $6 million to add new exhibits to the existing building. The Hall of Science officially opened as a museum on September 21, 1966. At first, there was no admission fee. Many of the original exhibits from the World's Fair were kept, like Atomsville USA. Other exhibits were changed or updated. For example, the basement auditorium became an exhibit about power plants. Each exhibit had a telephone or button to explain things to visitors. The Great Hall on the upper floors showed a space film. In total, the first exhibits covered about 25,000 square feet (2,300 m2).

Early Years and Challenges

By early 1967, about 2,000 children visited the museum every day. Within two years, two million people had visited, mostly school groups and families. More exhibits, like a replica of a lunar spacecraft's inside, were added in the late 1960s. In 1970, a fence and lights were put around the Space Park after the Atlas rocket was damaged. During the late 1960s and 1970s, money for the museum was often used for other city projects.

Unfinished Expansion Plans

In 1966, the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) offered up to $5 million for a nuclear-education center at the museum. The city accepted this offer and planned to add a nuclear science center and an exhibit building. The nuclear science center would have had a nuclear reactor, a playground, labs, and classrooms. The education building would have had more classrooms for experiments.

Plans for the five-story, 190,000-square-foot (18,000 m2) nuclear education center were announced in June 1967. The city gave $10.8 million for the project. Work on the expansion started in June 1968. In January 1969, the AEC announced plans for the museum's "atomarium," a 150-seat auditorium around a nuclear reactor. The reactor would have been in a pool under the atomarium.

Museum officials announced in 1970 that the building would close for renovations. The museum closed in mid-1971, but the Space Park stayed open. The city gave another $12.5 million for renovations. However, local residents protested when they learned the nuclear reactor would be a real one, not a model. By December 1971, the project stopped because of a lack of money and public opposition. The nuclear reactor plan was completely canceled.

The 1970s: Tough Times

Even after the expansion stopped, the museum was supposed to get $1 million for basic upkeep, but it never received these funds. Some small exhibits, a weather station, a hatchery, and a planetarium were added. Most of the objects in the Space Park were moved away because there wasn't enough money to take care of them. After some foundations donated money, the museum reopened on November 19, 1972. A planetarium was added in 1973.

By the mid-1970s, the area for the planned expansion was falling apart, and the Space Park was badly damaged and closed. The city government cut funding a lot during a financial crisis, and the museum couldn't even afford a climate control system. The museum reduced its hours and fired some staff. Its exhibits were old; one film from 1963 still predicted that people would land on the Moon someday! Because of the lack of investment, staff sometimes called it the "Hole of Science." Still, it was one of the most popular museums in the city and one of the most popular science museums in the U.S.

The museum tried to host more events in the late 1970s. In 1978, the Japanese government repaired the Space Park's Atlas rocket. In June 1980, a 23-foot-wide (7.0 m) geodesic dome with a greenhouse opened at the museum's entrance. The museum still had no climate control, and many parts of the building were not used.

1980s Renovation and Reopening

Starting Over

In 1980, the city government gave $2.9 million to completely renovate the museum, later increased to $3.5 million. The museum's board agreed to raise another $6 million for exhibits. The museum closed for renovation on January 5, 1981. The plan was to add 29,000 square feet (2,700 m2) of exhibit space, a media center, and a planetarium. Exhibits would be organized into five sections: the universe, matter, energy, biology, and communication.

During the closure, museum staff continued to offer programs at schools and set up exhibits in libraries. Work on the renovation began in June 1982. By then, the project cost had increased to $11 million. In July 1983, a report said the museum was too small and hard to reach. The city's cultural affairs commissioner stopped almost all funding and suggested moving the museum to Manhattan. The renovation stopped, leaving the museum with only three staff members. However, after discussions, the city restored funding in late 1983 and gave $1 million for exhibits in 1984.

A New Beginning with Alan Friedman

In September 1984, the city hired physicist Alan J. Friedman as the museum's new director. At that time, the museum had no exhibits, and the floor was flooded. Friedman quickly expanded the staff and decided to focus on interactive exhibits for children and programs for school groups. He planned exhibits on topics like astronomy, communications, light, and robotics. Workers added a third story for exhibits, offices, and classrooms. The museum also got a new roof and updated systems. The restored Hall of Science had 100 exhibits, many built by the Exploratorium.

The Hall of Science temporarily reopened in early 1985 with a traveling exhibit. Friedman also asked young visitors for their ideas before the official reopening. The museum officially reopened on October 8, 1986, after $9 million in renovations. It had 90 activities and exhibits. The museum hired 35 college students to explain and demonstrate the exhibits. Staff hoped the renovated museum would attract up to 700,000 visitors a year.

The museum continued to create new exhibits and programs in the late 1980s. Attendance grew by 25% each year for four years after it reopened. By the early 1990s, the museum had 150 interactive activities and over 250,000 visitors annually.

Museum Expansions

Growth in the 1990s

In 1991, the museum announced a big plan for renovation and expansion. The first part of this plan cost $13 million and included a two-story entrance building with an auditorium, gift shop, and cafeteria. This added 28,400 square feet (2,640 m2) of public space. Museum officials thought this expansion would increase visitors from 220,000 to 1.5 million people each year. Work began in December 1992. The museum stayed open during construction. A "Singing Shadows" exhibit was added in the mid-1990s. The Great Hall temporarily closed in 1994 after an accident.

In 1995, Friedman announced plans for a 20,000-square-foot (1,900 m2) science playground, costing $2 million. It would have many physics-themed exhibits. The new main entrance building was finished in April 1996. The auditorium opened in November 1996, and the science playground was completed in June 1997. Friedman received an award for his work in expanding the museum. In 1999, a permanent exhibit called Marvelous Molecules opened, and a "sound station" was added to the science playground.

Expansions in the 2000s

In 1998, money was set aside to restore Rocket Park. By then, the museum was planning a second expansion costing $55 million. This would include new exhibit space and restoring the rockets. The museum raised money by selling some items and seeking company sponsors. By early 2001, the museum had almost all the money needed. The Pfizer Foundation Biochemistry Discovery Lab opened in January 2001.

The museum's rockets were removed for restoration in August 2001. After the September 11 attacks, the museum had less money and fewer visitors, so it had to cut staff and operating hours. Even so, work on the second expansion began in October 2001. The city government provided most of the budget, which had grown to $68 million. The renovation included building a new wing called Science City, which would double the museum's size. This project was planned to finish in late 2004.

The original museum stayed open during the expansion. The rockets were reinstalled in October 2003. The science playground reopened in April 2004 after a renovation, and Rocket Park was officially dedicated on September 30, 2004. The new north wing opened on November 24, 2004. This second expansion cost $89 million in total. Alan Friedman retired in 2006. By then, the museum had 450,000 visitors each year. A miniature golf course opened at the museum in June 2009.

2010s to Today

In 2009, the museum began restoring the original Great Hall building. This renovation was completed in June 2015. A new permanent exhibit was added to the Great Hall. By this time, the museum had 450 exhibits and half a million visitors annually.

In 2016, a pre-kindergarten school was announced next to the Hall of Science. The museum helped develop the school's STEM curriculum. Construction for the school started in 2019. The science playground also closed for renovation that year.

The New York Hall of Science temporarily closed in March 2020 due to the coronavirus pandemic. It reopened in July 2021 but had to close again in September after Hurricane Ida caused flooding. The flood damaged half of the exhibits in the basement. The museum partially reopened in February 2022, and the rest of the museum reopened in October 2022 after new exhibits were added. The mini-golf course was also renovated in 2022, and the science playground reopened in October 2023. Lisa Gugenheim became the museum's president in September 2024.

Museum Exhibits

NYSCI has permanent exhibits, plus temporary shows and programs. After its 1986 reopening, the museum focused on hands-on exhibits about technology and science for children. They also host live science demonstrations. The museum is part of the Association of Science and Technology Centers.

Permanent Exhibits

Since the 1980s renovation, the Hall of Science has focused on interactive exhibits that visitors can touch and operate. Many exhibits use everyday objects, like a stationary bicycle that powers a propeller. Small signs next to each exhibit explain the science behind it. A real Mercury capsule hangs from the ceiling in the original building's basement.

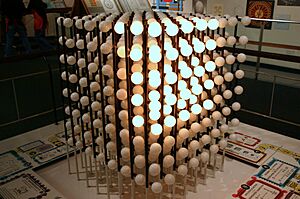

The original building has many interactive exhibits. For example, there's an atomic model and an optical-illusion exhibit with light and mirrors. The museum also has a microbiology exhibit called Hidden Kingdoms, with microscopes and an aquarium. There's a biochemistry lab with 12 hands-on experiments. Other exhibits include "Powering the City," about New York City's power grid, and "Small Discoveries," about tiny living things called microorganisms. IBM's traveling Mathematica exhibit was added in 2004. The Great Hall's first permanent exhibit, "Connected Worlds," opened in 2015. The museum also has fun activities like bubble-making stations.

When the north wing was built, it included exhibits about the science of art, technology, sports, and even extraterrestrial life. This wing has interactive replicas of a Mars rover, online arm-wrestling and car-racing games, and sports challenges like a surfing simulator. The ground floor of the north wing has "Human Plus," an exhibit about technology for people with physical disabilities, and a play area for young children. Since 2021, the north wing has hosted an exhibit about happiness. Also, since 2025, the museum has featured CityWorks, an interactive exhibit about how a city's infrastructure works.

Temporary Exhibits

The Hall of Science has hosted many temporary exhibits over the years. In the early 1970s, these included art shows that demonstrated science, films about space, and exhibits about local history. Other exhibits in the late 1970s and early 1980s featured minerals, wood-burning stoves, and the aviation industry. In 1985, the museum hosted 60 interactive exhibits as part of the Science Circus.

After the 1980s renovation, temporary exhibits were shown in the Great Hall. These included sound installations and exhibits on topics like construction equipment, early scientific discoveries, sports training, and health. The museum also set up exhibits in other parts of the city, like displays on bus stops and an exhibit about manhole covers. In the late 1990s, the museum hosted exhibits based on TV shows like The Magic School Bus and Beakman's World, as well as traveling math shows and interactive light art.

The museum continued to host temporary exhibits in the 2000s, covering topics like reptiles, sports, robotics, and surgery. In the 2010s, exhibits included shows about cartoons, dinosaurs, and Angry Birds-themed physics demonstrations.

Programs and Learning

The museum offers many programs to help students learn. In its early years, it had test-prep classes for high school students and a Space Age Stargazers program. In the 1970s, it hosted summer classes for children and amateur-radio operation classes. After reopening in 1986, the museum started a program where science students could get help with tuition if they taught science in New York City schools. In the 1990s, the museum trained public-school teachers and hosted workshops for students from pre-kindergarten to 8th grade. It also added a JROTC program and an astronomy lab in 1993.

The museum has a research center called the Sara Lee Schupf Family Center, named after a generous donor. The New York Hall of Science also includes the Alan J. Friedman Center, a youth education center. One of its programs is the Science Career Ladder, which has been running since the 1980s. In this program, high school and college students work as docents, explaining science to visitors. Other programs include teacher training, a Girls in Tech program, a STEM course for older adults, and after-school programs in libraries. Since the 2020s, the museum has hosted interactive events for families as part of its Summertime at NYSCI program. Students from the nearby Mosaic Pre-K Center get free museum memberships and attend classes at the museum.

To support its programs, museum staff invented a portable planetarium dome for schools and a special high-resolution microscope. The Hall of Science also created websites related to its exhibits, like TryScience, a science website for children launched in 2000.

Events and Fun Activities

The Hall of Science organizes many different events. Early events included paper airplane contests, science fair competitions, and spacecraft watch parties. After the 1980s renovation, events included flight demonstrations, science-themed circus shows, Bug Day events, and Halloween parties. Some events celebrate specific moments, like eclipse watch parties for the solar eclipse of April 8, 2024. In 1989, the museum collected telegrams from visitors to be placed on Space Shuttle Atlantis. In 2022, the museum even had an indoor skating rink. The Great Hall can also be rented for private events.

There are also seasonal events. The Queens Night Market happens every year in the museum's parking lot, from April to October. Informal ecua-volley courts are also set up there in the summers. The New York Hall of Science started hosting Maker Faire, a do-it-yourself science and technology convention, in 2010. It was held annually until 2019. For several years in the 2010s, the museum hosted the Gingerbread Lane display during the holiday season. During the pandemic, the museum hosted community events like food drives and COVID-19 vaccinations. The museum has also hosted sleepover events over the years.

Museum Building and Outdoor Areas

The New York Hall of Science is located at 47-01 111th Street in Flushing Meadows–Corona Park in Queens, New York City. The museum's parking lot has 63 concrete security posts that show how parts of the Earth get sunlight during the summer solstice. Next to the museum is the Mosaic Pre-K Center.

Original Building Design

The original building, designed by Wallace K. Harrison, was a pavilion that covered 21 acres (8.5 ha). Its base is a hexagonal structure. Above the base is the Great Hall, which is shaped like an amoeba with a curving concrete wall. This part of the building is 80 feet (24 m) high. The outside wall is made of 22 curved panels, each 13 inches (330 mm) thick. Each panel has a grid of 9 by 28 rectangles. These rectangles were made using a special method called dalle de verre, where blue glass pieces are set into the concrete. In total, there are 5,400 rectangles.

The main entrance was through a gap in the wall and a reflecting pool, where visitors went through revolving doors. A long ramp led to this entrance. Inside, the Great Hall is supported by huge concrete beams. The hexagonal base, called the Central Pavilion, was connected to the Great Hall by stairs and an elevator. A third level for exhibits, with 15,000 square feet (1,400 m2) of space, was added in the 1980s.

Main Entrance Building

The main entrance building was finished in 1996 and designed by Beyer Blinder Belle. It faces west toward 111th Street, not east toward the park, because the architects wanted it to "face the city." This building has a rotunda that is 47 feet (14 m) high. It includes a dining room, gift shop, cloakroom, a 300-seat auditorium, and computer rooms. On the second floor of the rotunda, there's an artwork by Fred Tomaselli called Ten Kilometer Radius. It has 72 peepholes, each showing a building within 6.2 miles (10 km) of the museum that can be seen from that direction.

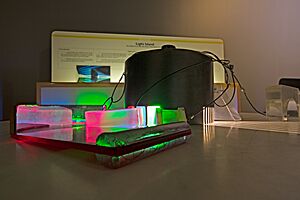

North Wing

Todd H. Schliemann designed the north wing, also known as the Hall of Light. This wing covers 55,000 square feet (5,100 m2). Unlike the original building, which has few windows, the north wing is designed to let in lots of natural light. The first floor of the north wing is set back from the second floor and has a glass front. This transparent base was meant to show visitors what's inside. The roof and walls are made of Kalwall, a special material that lets light through. At night, the north wing glows from the inside.

Inside, you can see the north wing's structure and mechanical systems, which are part of the design. Steel beams and pillars hold up the building. A central staircase connects the entrance building to both the original Hall of Science and the new north wing. The north wing also features the Light Wall, an artwork by James Carpenter, which is a sloped glass pane with small holes. Three spaces for temporary exhibits and several permanent exhibits were added when the north wing was built.

Attached to the north wing is the Viscusi Gallery, an oval-shaped gallery covering 4,000 square feet (370 m2). This gallery, on the second floor, has no windows and is used for temporary exhibitions. Below it, on the first floor, are offices and a library with glass walls.

Outdoors Attractions

Rocket Park

Next to the New York Hall of Science is Rocket Park, which was originally a 2-acre (0.81 ha) exhibit at the World's Fair called the Space Park. During the fair, it displayed 23 spacecraft or parts of spacecraft. Today, Rocket Park includes an Atlas rocket and a Titan II rocket. The Atlas rocket is 102 feet (31 m) high, and the Titan rocket is 110 feet (34 m) high. These rockets were built in 1961 for the United States Air Force but were never used for military purposes; instead, they were shown at the 1964 World's Fair. The rockets were rebuilt in 2003 with new foundations and fresh paint. Two replicas of space capsules were added during the 2000s renovation.

Inside Rocket Park, there's a nine-hole miniature golf course. It has obstacles that teach kids about physics. For example, one hole has a spinning wheel where you have to hit the ball at the right time, and others have loops and tunnels. Playing mini-golf costs an extra fee.

Science Playground

Outside the museum is the 60,000-square-foot (5,600 m2) Science Playground, designed by BKSK Architects. It's for children aged 6 and older, but adults can use it too. The Science Playground has an extra admission fee and is open from March through December. It originally had up to 30 exhibits or play structures, each designed to teach physics concepts. College students help explain the science to children in the playground.

The playground was inspired by playgrounds Alan Friedman saw in India. Many pieces of equipment are brightly colored and show architectural and engineering ideas. The playground has a wobbly bridge, a large spider web made of rope, slides, speaking tubes, and a huge seesaw. Other exhibits focus on water, like an Archimedes' screw, a whirlpool, and a table with a stream. The playground also includes a water play area, sandboxes, and a "sound station" with pipes, bells, and xylophones.

How the Museum is Run

The New York Hall of Science is run by a nonprofit organization that focuses on science exhibits, events, and education. It's part of the Cultural Institutions Group in New York City. In 1996, the museum was officially named a New York City cultural institution.

Funding the Museum

Since the city government owns the museum building, they have to approve any increases in ticket prices. In the 1960s, the city provided one-third of the museum's budget, with the rest coming from donations. This continued into the 1970s, when the museum had a $500,000 annual budget. In the late 1980s, the museum spent $3.5 million annually, growing to $5 million by the early 1990s. Two-fifths of the money came from the city, and the rest from tickets, grants, and donations.

Funding was reduced in the early and late 1990s. The Hall of Science worked with the Liberty Science Center in New Jersey to raise money for both museums. By 1998, the Hall of Science's budget was $7.5 million, with 35% coming from ticket sales and renting out the building for events.

In the early 2000s, the museum faced more money problems. Its budget was $8 million by 2001 and $11.5 million by the mid-2000s. By then, the city government's share of the budget had dropped to 13%. In 2005, the museum received part of a $20 million grant. Today, the museum continues to get money from ticket fees, government agencies, and private donors. In the fiscal year 2023, it had $19.2 million in income and $21.3 million in expenses.

Visitors and Attendance

In its first two years, the museum had two million visitors. Most early visitors were students on class trips or families. In the 1970s, the museum had about 3,000 visitors daily and often saw 10,000 to 20,000 visitors on weekends. Visitor numbers grew a lot in the late 1990s, with 296,000 visitors in 1998. At that time, the museum often reached its daily limit of 1,500 visitors in June and July. By 2006, the museum had 450,000 annual visitors, and by the mid-2010s, it had half a million visitors each year.

See also

In Spanish: New York Hall of Science para niños

In Spanish: New York Hall of Science para niños

- 1964 New York World's Fair pavilions

- List of museums and cultural institutions in New York City

| Mary Eliza Mahoney |

| Susie King Taylor |

| Ida Gray |

| Eliza Ann Grier |