Nicolas Coccola facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Nicolas Coccola

|

|

|---|---|

Father Nicolas Coccola

|

|

| Born | December 12, 1854 |

| Died | March 1, 1943 Smithers, British Columbia

|

| Occupation | Oblate missionary |

| Parent(s) | Jean and Elise di Coccola |

Nicolas Coccola (born December 12, 1854 – died March 1, 1943) was a French missionary. He came to British Columbia, Canada in 1880 and worked there until he passed away in 1943.

For 63 years, he served in many parts of British Columbia. He worked with several First Nations groups. These included the Shuswap, Kootenai, Dakelh, Sekani, Gitxsan, Hagwilget, Babine, and Lheidli T'enneh peoples.

Contents

Life in British Columbia

Nicolas Coccola left France on June 6, 1880. He sailed on a ship called the SS Gascoigne. Thirteen days later, he arrived in New York City. From there, he took a train to San Francisco. Then, he boarded a small boat and reached New Westminster on July 26.

At the St. Mary's Mission, Coccola continued his studies. In 1881, he became a Roman Catholic priest. He was then sent to Kamloops.

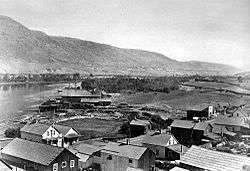

In 1881, Kamloops was a new settlement. It had only two stores and two hotels. The local First Nations camp was about 5 kilometers (3 miles) outside the village. It had thirty homes, a school, and a church. When Coccola arrived, he joined other missionaries. They lived in a log cabin.

Coccola spent much time building homes and working in gardens. He also often helped people with medical needs. There was no doctor in the area. Once, he brought medicine to a Chief's son. The man got better, and Coccola was asked to help more sick people. He traveled to Fountain and Lillooet to do this.

In August 1883, Coccola and other missionaries heard news. The Canadian Pacific Railway was building tracks into British Columbia. More missionaries were needed to help the workers. Nicolas Coccola went to the railway construction camps. He often stayed in the workers' bunkhouses. He gave communion, taught lessons, and heard confessions. He traveled from camp to camp, reaching Rogers Pass.

In the fall of 1883, he arrived in Donald. The railway tracks had reached the town. About 300 people lived there in tents and shacks. Coccola held Mass wherever he was invited. He also prepared children in Donald and nearby Golden for their first Communion. In November 1884, Coccola was at Craigellachie. This is where the last spike of the Canadian Pacific Railway was driven. After the railway was finished, he returned to Kamloops.

St. Eugene Mission Work

In the fall of 1887, Nicolas Coccola was sent to the St. Eugene Mission. This mission was near Moyie and north of Cranbrook. It was about 200 kilometers (124 miles) from Golden. River travel had stopped for the year. So, a Shuswap family guided Coccola to the mission.

The St. Eugene Mission had a large garden. It grew fresh food for the mission residents. It also supplied local miners. There were few white settlers in the area. Many had left because they worried about the local Kootenai First Nations. This worry came from 1884. Two Kootenai men were arrested for murder. Chief Isador learned there was no proof. He led thirty warriors to Wild Horse Creek. They broke the two men out of jail.

Chief Isador defended his actions. He said, "If it can be found that these men are guilty, I will be the first to punish and deliver them. How many Indians have been found killed and white men not arrested?" The Chief then told the judge and others to leave within 24 hours. When Coccola arrived in 1887, settlers had asked for protection. The North-West Mounted Police (now the Royal Canadian Mounted Police) set up a post. It was at Fort Steele, about 11 kilometers (7 miles) from the mission.

Coccola's work at St. Eugene Mission was similar to his duties in Kamloops. Besides his regular tasks, he often provided medical help. There were few doctors, and influenza was common. In October 1890, a residential school opened at the mission. It had 20 students. Coccola often visited and held Mass in towns like Ainsworth, Kaslo, and Nelson. Churches and hospitals were being built there for new settlers.

In the fall of 1891, two Kootenai women found a shiny rock. They were picking berries near the St. Mary's River. They carried it for a while, then left it. Joseph Bourgeois found the rock. This led to the North Star Mine. The next year, Donald Mann bought it for $40,000.

This story made Coccola think. He told the Kootenai people that mining could be good for them. He advised them to look for similar rocks. In April 1893, a Kootenai man named Pierre showed Coccola a special stone. He led Coccola to where he found it near Moyie Lake. Coccola quickly went to Fort Steele. He registered for a miner's license. He sent samples of the rock to Spokane for testing.

The tests showed the rock had a lot of silver. Coccola, Pierre, and a developer named James Cronin each claimed land near Moyie Lake. They registered their claims on June 25. Pierre and Father Coccola sold their claims in 1895 for $12,000. Father Coccola became known as the "miner priest." He used his share of the money to build a hospital and a new gothic church at the St. Eugene Mission. He also built another church in Moyie.

Over the next ten years, the St. Eugene Mine produced over $10,000,000 worth of ore. This mine helped start the Consolidated Mining and Smelting Company, later known as Cominco.

Fort George and Later Years

By 1911, Nicolas Coccola often visited the Lheidli T'enneh First Nations village at Fort George. This area later became Prince George. He worried about the bad influences from railway workers and settlers. There was a large hotel in the nearby town of South Fort George. The First Nations village was valuable land. It was decided that the railway would pass through Fort George. Many groups wanted to buy the land.

Eventually, the railway successfully bought the 1,366-acre (5.5 km²) property. Nicolas Coccola spoke for the First Nations band. The village was sold for $125,000. A new reservation was built about 16 kilometers (10 miles) north on the Fraser River. By the summer of 1913, the old First Nations village was burned down. Only the church was left standing.

On August 31, 1913, Coccola blessed the new reservation and its church. Many people from Fort George came by boat to watch. He then went back to Fort St. James and Stoney Creek for the winter. In the spring of 1914, he traveled to Smithers. Three lots had been bought there to build a church. He also visited Prince Rupert and checked on the church at Moricetown. In April, the Grand Trunk Pacific Railway was completed. But August brought the start of World War I, and Coccola returned to Fort St. James.

By 1917, Prince George, Fort St. James, and Hagwilget each had their own priests. Coccola held Mass and served in other towns along the railway. These included Vanderhoof and McBride. In the fall of 1918, the Spanish flu epidemic spread through the region. In Stoney Creek, one-third of the people died. At Fort St. James, 14 people died and were buried on a single day. Some victims died in the wilderness and were never found.

Lejac Residential School

In 1921, construction began on a new residential school. It was built on Fraser Lake. The Lejac Residential School was finished on January 17, 1922. Staff and students moved there from the old school at Fort St. James. That same year, a new St. Joseph's church was built for Fort Fraser. Coccola became the principal of the Lejac school that fall. He worked there on and off until 1925. He then went to Vancouver for an operation and visited his old St. Eugene Mission. He returned to the Lejac school and stayed until 1934. Then, he became the chaplain at the Sisters of the Child Jesus Hospital in Smithers.

In 1936, a surveyor named Frank Swannell suggested naming Mount Coccola near Hazelton after him.

At Easter in 1940, Coccola was retired from missionary work. However, he was called to Moricetown. The residents had no priest for the holiday. They wanted to have Mass and Communion.

After his last duties as a missionary, Nicolas Coccola returned to Smithers. He passed away there on March 1, 1943.

| Tommie Smith |

| Simone Manuel |

| Shani Davis |

| Simone Biles |

| Alice Coachman |