Nonjuring schism facts for kids

The Nonjuring schism was a big split in the main churches of England, Scotland, and Ireland. It happened after King James II was removed from power in 1688 during an event called the Glorious Revolution.

To keep their jobs, church leaders (called clergy) had to promise loyalty to the new rulers, William III and Mary II. But for different reasons, some refused to take this oath. These people were called Non-jurors, which comes from a Latin word meaning "to swear an oath."

In the Church of England, about 2% of priests, including nine bishops, refused the oath in 1689. Most ordinary clergy were allowed to stay, but six bishops who refused were removed in 1691. A separate Non-Juror Church was formed in 1693 when Bishop Lloyd chose his own bishops. However, most English Non-Jurors stayed within the main Church of England. This Non-Juror Church was never very large and mostly disappeared after 1715.

In Scotland, the church changed a lot in 1690. It removed bishops and became a Presbyterian church, known as the kirk. Ministers who didn't accept these changes were removed. This led to the creation of a separate Scottish Episcopal Church in 1711. When George I became king in 1714, most Scottish Episcopalians refused to promise loyalty to him. This split lasted until Charles Stuart died in 1788.

The Non-Juring movement in the Church of Ireland was very small. However, it did include Charles Leslie, who wrote a lot supporting James II. The Episcopal church in North America was part of the Church of England back then. It wasn't much affected until after the American Revolution, when the Scottish Non-Juror church's ways influenced the new U.S. Episcopal Church.

Contents

Why the Split Happened

In the 1600s, being a Presbyterian or an Episcopalian meant more than just how a church was run. It also showed political differences. Episcopalian churches were led by bishops chosen by the king. Presbyterian churches were led by elders chosen by the church members. People believed that "true religion" and "true government" were the same. So, arguments about church rules often showed political disagreements.

In 1688, the main churches in England, Scotland, and Ireland all had bishops and were Protestant. But they faced different problems. In England, most people belonged to the Church of England. In Ireland, most people were Catholic. The Church of Ireland was a small group, even among Irish Protestants. In Scotland, almost everyone belonged to the Church of Scotland, which was a mix of both systems.

King James II became king in 1685 with a lot of support. But his actions seemed to go beyond just allowing Catholicism. They looked like an attack on the main church. People remembered the dangers of religious fights from the Wars of the Three Kingdoms (1638-1652). Many wanted to avoid another big split.

James made many people angry when he put the Seven Bishops on trial in June 1688. Many felt he had broken his promise to protect the Church of England. This made the idea of loyalty oaths a very important issue.

English Non-Juring Movement

"Non-Juror" usually means those who refused to take the Oath of Allegiance to the new rulers, William III and Mary II. It also includes "Non-Abjurors," who refused a later oath in 1701 or 1714. This later oath made them deny that the Stuart family had a right to the throne.

Nine bishops became Non-Jurors, including the top bishop, William Sancroft, the Archbishop of Canterbury. Five of the seven bishops King James had put on trial also became Non-Jurors. About 339 clergy members (around 2% of the total) became Non-Jurors. Many of them were in cities like London and Newcastle.

It's harder to count regular church members who were Non-Jurors, as only public officials had to take the oath. People refused for different reasons. Some, like Bishop Thomas Ken, felt they had to keep their promise to King James, but they didn't oppose the new government. Others believed the new rulers were not legitimate because kings were chosen by God and couldn't be removed. This was called the "state point." A deeper reason was the "church point," which meant Parliament had no right to interfere in church matters, like choosing bishops or changing church rules.

History of the English Non-Jurors

Most regular clergy were not bothered. The Non-Juring bishops were suspended in February 1690, but William tried to find a way to compromise. When this failed, Parliament appointed six new bishops in May 1691.

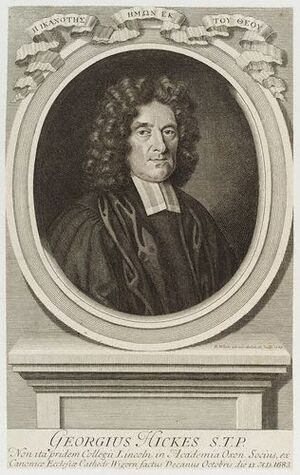

In May 1692, Archbishop Sancroft gave his powers to Bishop Lloyd. In May 1693, Lloyd chose Thomas Wagstaffe (1645–1712) and George Hickes (1642–1715) as new Non-Juring bishops. Lloyd said he just wanted to show that Parliament couldn't remove or appoint bishops. But this created a formal split. Most Non-Jurors stayed within the main church.

Some important Non-Jurors, like Henry Dodwell (1641–1711) and Robert Nelson (1656–1715), returned to the main church in 1710. Hickes, who strongly believed in the divine right of kings, was the main leader of the Non-Juror church. It quickly declined after he died in 1715.

To keep the church going, Hickes and two bishops from the Scottish Episcopalian Church chose new bishops in June 1713.

In 1719, the Non-Juror church split again into "Usager" and "Non-Usager" groups. Both groups chose their own bishops. The Non-Usagers wanted to eventually rejoin the main Church of England. The Usagers wanted to bring back older church services, like the 1549 Book of Common Prayer. The Usagers even talked with the Greek Orthodox Church about joining together, but it didn't work out. Even though the two groups agreed to reunite in 1732, disagreements continued.

By the early 1740s, only a few Non-Juror churches were left in places like Newcastle, London, and Manchester. The last regular Non-Juring bishop, Robert Gordon, died in 1779. His church in London joined the Scottish Episcopal church. A small group in Holborn was very loyal to the Stuarts. They refused to recognize King George III in 1788 and disappeared in the 1790s.

How Many and Why They Mattered

At first, the separate Non-Juror church was mostly for clergy. Later, regular people joined. It's hard to know exact numbers because their churches often moved. But they were probably very few, even fewer than Catholics. Many more people were "crypto-Non-Jurors." These people stayed in the main church after 1693 but shared some Non-Juror ideas. They were sympathetic to the Stuarts but usually not active Jacobites.

A good example of this group was Lady Elizabeth Hastings. She was a wealthy Tory who believed in a strong Church of England. These "crypto-Non-Jurors" cared about the "church point." They opposed things that seemed to weaken the Church of England, like the 1689 Toleration Act, which gave some freedom to other Protestants.

Because of this, the fact that the Stuarts were Catholic was a huge problem for them to return to the throne. Even so, some tried to convert James and his family. When Prince Charles visited London in 1750, he joined the Non-Juring church.

Even though there were few Non-Juror clergy, they had a big impact on church policy. Many opposed changes after 1689 that moved the Church of England away from its traditional authority. This led to calls for the church assembly (called Convocation) to have more say. This was often a fight between mostly Tory, High Church clergy and Whig bishops.

Outside of politics, the Non-Juror movement had a greater impact than people often realize. Lady Elizabeth Hastings was part of a group of rich, High Church people who gave money to help stop "un-Christian behavior." This included trying to convert Catholics and other Protestants. In 1698, this group started the Society for the Propagation of Christian Knowledge (SPCK). In 1701, they started the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts (SPG). Both groups still exist today.

Some Non-Jurors later became early supporters of Methodism, which started as a reform movement within the Church of England. One was Selina Hastings (1707–1791), Lady Elizabeth Hastings' daughter-in-law. She founded an evangelical Methodist group. Methodists were often accused of supporting Jacobitism because they rejected existing church ways.

Even though they were linked to traditional ideas, "crypto-Non-Jurors" also included Mary Astell (1666–1731). She was an educationalist sometimes called the first English feminist. Her father was a wealthy Non-Juror merchant. In 1709, she started a girls' school in Chelsea, London. It was supported by the SPCK and other Non-Jurors. It's believed to be the first school in England with an all-women board of governors.

Irish Non-Juring Movement

The Church of Ireland was a small group, even among Irish Protestants. During the 1689 Parliament called by King James, four bishops were in the Lords. Anthony Dopping, Bishop of Meath, led the opposition.

Non-Juror Henry Dodwell was born in Ireland but worked in England. So, William Sheridan, Bishop of Kilmore and Ardagh, was the most important Irish Non-Juror. He lost his job and later died poor in London. Only a few Irish clergy followed him. The most famous was Jacobite writer Charles Leslie.

Like in England, many Irish clergy agreed with some Non-Juror ideas. For example, John Pooley, Bishop of Raphoe, avoided taking the Oath of Abjuration until 1710. Bishop Palliser often wrote to Dodwell. Bishop Lindsay, who later became Archbishop of Armagh, was a close friend of Jacobite plotter Francis Atterbury. Lindsay himself was accused of Jacobitism in 1714. However, most of these connections seemed to be based on friendship, not strong political beliefs.

Scottish Non-Jurors and the Scottish Episcopal Church

In England, the Non-Juring split was mostly within the Episcopalian church. But in Scotland, it was different. In 1688, Scots were split almost equally between Presbyterians and Episcopalians. Episcopalians were mostly in the Highlands and some eastern areas.

The 1690 General Assembly of the Church of Scotland got rid of bishops. It also removed 200 ministers who refused to accept these changes. Many ministers stayed in their jobs even after being removed. For example, Michael Fraser served as a minister from 1673 to 1726, even though he was removed in 1694 and joined two Jacobite uprisings.

Moderates in the kirk helped removed ministers return. From 1690 to 1693, 70 of the 200 returned after taking the Oath of Allegiance. Another 116 returned after the 1695 Act of Toleration. In 1702, about 200 of 796 parishes were held by Episcopalian ministers. But many of these were not Non-Jurors.

Before 1690, the main differences were about how the church was run. But as their numbers dropped, Scottish Episcopalians focused more on their beliefs. They saw the 1707 Union (when Scotland joined England) as a chance to regain power through a united British church. They started using English church services to help this. The Scottish Episcopalians Act 1711 gave the Scottish Episcopal Church a legal basis. The 1712 Toleration Act protected their use of the Book of Common Prayer, which had caused a war in 1637.

When George I became king in 1714, the church split. Most became Non-Jurors, and a smaller group became "Qualified Chapels" who were willing to swear loyalty to the new king. Being a Non-Juring Episcopalian became a sign of supporting the Jacobites. Many people from this group joined the 1745 Jacobite uprising.

After 1745, many Non-Juror meeting places were closed or destroyed. More rules were put on their clergy and members. When Prince Charles died in 1788, his brother Henry, a Catholic Cardinal, took over as the Stuart claimant. The Episcopal Church then swore loyalty to George III, ending the split with the Qualified Chapels.

In 1788, Bishop Charles Rose and one priest, James Brown, refused to recognize George III. They formed a separate Non-Juring church in Edinburgh that supported Henry Stuart. However, this church ended in 1808 when their last clergyman died. When the laws against them were finally removed in 1792, the church had fewer than 15,000 members. Today, the Scottish Episcopal Church is sometimes jokingly called the "English Kirk."

Non-Jurors in North America

The political fights of the 1688 Glorious Revolution also affected British colonies in North America and the Caribbean, but less strongly. Because Catholic New France was nearby, there was little sympathy for King James. In 1700, New York even banned Catholic priests. However, Virginia removed several Non-Jurors from office in 1691.

Richard Welton became a Non-Juror in 1714 and lost his church in Whitechapel. In 1724, he was made a bishop by a Non-Usager bishop and moved to North America. He took over as the leader of Christ Church, Philadelphia. This caused a dispute with the previous leader.

There weren't many Episcopalian ministers in North America. One reason was the delays in London approving appointments. Between 1712 and 1720, John Talbot, a rector, asked many times for a bishop to be appointed. On a trip to England in 1722, he was made a Non-Juror bishop. When the governor told the church authorities, Talbot and Welton were suspended. Talbot stayed in North America and died in 1727. Welton returned to England in 1726 and died soon after.

A colonial bishop was not appointed partly because American Protestants who were not Anglicans opposed it. They saw it as an attempt to force a state church on them. In 1815, John Adams said that fear of a strong Episcopalian church helped get people to support the American Revolution in 1773.

After the Revolution began, many Episcopal ministers stayed loyal to the British government and were removed. In Pennsylvania, most supported the American side, including William White. He created the rules for the new American Episcopal Church. All states accepted these rules except Connecticut, which wanted each state to have its own bishop.

Connecticut sent a loyalist, Samuel Seabury, to England to become a bishop. But he couldn't take the required Oath of Allegiance to George III. So, he was made a bishop by the Scottish church in November 1784. The British Parliament, worried about another church split, agreed to waive the oath. On February 4, 1787, White was made Bishop of Pennsylvania by the Archbishop of Canterbury.

Images for kids

-

Lady Elizabeth Hastings, a wealthy High Church Tory. Her influence was much greater than the small number of Non-Jurors.

| Leon Lynch |

| Milton P. Webster |

| Ferdinand Smith |