Northern bald ibis facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Northern bald ibis |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| captive adult | |

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification |

|

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Pelecaniformes |

| Family: | Threskiornithidae |

| Genus: | Geronticus |

| Species: |

G. eremita

|

| Binomial name | |

| Geronticus eremita (Linnaeus, 1758)

|

|

|

|

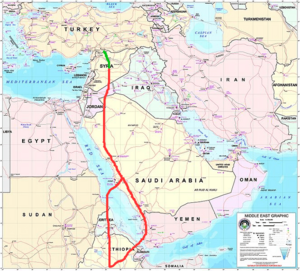

| Map showing location of remaining colonies in Morocco | |

| Script error: The function "autoWithCaption" does not exist. | |

Script error: No such module "Check for conflicting parameters".

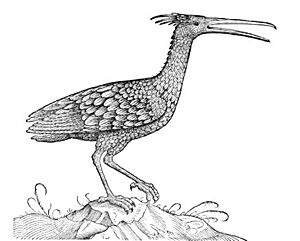

The northern bald ibis, also called the hermit ibis or waldrapp (Geronticus eremita), is a special bird found in open areas. These include grasslands, rocky mountains, and semi-deserts, often near rivers. This bird is about 70–80 cm (28–31 in) long and has shiny black feathers. Unlike many other ibises, it doesn't wade in water. It has a red face and head without feathers, and a long, curved red beak.

Northern bald ibises build their nests together on cliff ledges along coasts or in mountains. They usually lay two to three eggs in a nest made of sticks. They eat lizards, insects, and other small animals.

Long ago, the northern bald ibis lived across the Middle East, northern Africa, and parts of Europe. Fossils show they have been around for at least 1.8 million years! But they disappeared from Europe over 300 years ago. Today, there are programs trying to bring them back to Europe. In 2019, there were about 700 wild birds left in southern Morocco. Sadly, fewer than 10 were in Syria, where they were found again in 2002, but their numbers have dropped since then.

Because their numbers were so low, people started reintroduction programs around the world. In Turkey, a semi-wild group grew to almost 250 birds by 2018. There are also projects in Austria, Italy, Spain, and northern Morocco. These efforts, along with natural growth in Morocco (from about 200 birds in the 1990s), helped the northern bald ibis. In 2018, its status on the IUCN Red List improved from Critically Endangered to Endangered. About 2000 northern bald ibises live in zoos and special centers.

One reason for their decline in Europe was hunting, especially for young birds. Since these ibises don't reproduce very quickly, hunting them led to their disappearance in many places.

Contents

What is a Northern Bald Ibis?

Ibises are social birds with long legs and long, curved beaks. They are related to spoonbills. The northern bald ibis's closest relative is the southern bald ibis, which lives in southern Africa. These two types of ibises are unique because they have no feathers on their faces and heads. They also build nests on cliffs and prefer dry places, unlike other ibises that live in wetlands.

The northern bald ibis was first described in a book in 1555 by a Swiss naturalist named Conrad Gesner. Later, in 1758, Carl Linnaeus gave it its scientific name, Upupa eremita. It was later moved to its current group, Geronticus, in 1832. This bird has a fascinating history of being described, then forgotten, and then found again!

The name Geronticus comes from an old Greek word meaning "old man." This refers to the bird's bald head. Eremita is a Latin word for "hermit" or "desert dweller," which describes the dry places where this bird lives. Another common name, waldrapp, is German for "forest raven."

How to Identify a Northern Bald Ibis

The northern bald ibis is a large bird, about 70–80 cm (28–31 in) long. Its wingspan can be 125–135 cm (49–53 in), and it weighs about 1.0–1.3 kg (35–46 oz). Its feathers are black and shiny, with hints of bronze-green and purple colors. It has a fluffy ruff of feathers on the back of its neck. The face and head are dull red and have no feathers. Its long, curved beak and legs are also red.

When it flies, the northern bald ibis uses strong, shallow wing beats. It makes guttural "hrump" and high, hoarse "hyoh" sounds at its nesting sites, but it's usually quiet otherwise.

Male and female ibises look similar, but males are generally bigger. Males also have longer beaks, which helps them attract a mate. Young chicks have light brown feathers. As they grow, their heads and necks slowly turn red, like the adults. Birds from Morocco tend to have longer beaks than those from Turkey.

| Where they live | Male beak length | Female beak length |

|---|---|---|

| Morocco | 141.1 mm (5.56 in) | 133.5 mm (5.26 in) |

| Turkey | 129.0 mm (5.08 in) | 123.6 mm (4.87 in) |

You can tell the northern bald ibis apart from its relative, the southern bald ibis, because the southern one has a whitish face. The northern bald ibis is also bigger and sturdier than the glossy ibis, which looks similar and lives in some of the same areas.

Where Northern Bald Ibises Live

Unlike many other ibises that nest in trees and feed in wet areas, the northern bald ibis nests on quiet cliff ledges. They look for food in dry, open areas like semi-dry grasslands and empty fields. It's important for them to have good feeding areas close to their nesting cliffs.

The northern bald ibis used to live all over the Middle East, northern Africa, and parts of Europe. They nested on cliffs and even on old castle walls. But they disappeared from Europe about 300 years ago. Today, almost all the wild northern bald ibises (over 500 birds) live in Morocco. They are found in Souss-Massa National Park and near the mouth of the Oued Tamri.

In Turkey, a group of ibises survived for a long time because people believed the birds guided Hajj pilgrims to Mecca. This made the ibis a protected bird. A festival was even held each year to celebrate their return. This group lived near the town of Birecik. In the early 1900s, there were about 500 breeding pairs, and around 3,000 birds in total by 1930. But by the 1970s, their numbers dropped a lot. A special program started in 1977 to breed them in captivity. By 1992, the wild population in Turkey was gone. Now, the Birecik group is kept in a semi-wild state, free for most of the year but caged in autumn to stop them from migrating.

After the wild Turkish group disappeared, people thought the northern bald ibis only lived in Morocco. But in 2002, surveys found a small group of seven birds still breeding near Palmyra in Syria! This was a big surprise, as the bird was thought to be extinct in Syria for over 70 years. However, hunting and changes to their habitat caused their numbers to drop quickly.

The ibises in Morocco stay there all year. It's thought that the coastal fog helps keep the area moist enough for them. In other parts of their old range, the northern bald ibis used to fly south for the winter.

Scientists used satellite tags on 13 Syrian birds in 2006. They found that three adults (plus one untagged bird) spent the winter in the highlands of Ethiopia. They flew south along the eastern side of the Red Sea, through Saudi Arabia and Yemen. They returned north through Sudan and Eritrea.

Northern Bald Ibis Life Cycle

Reproduction

Northern bald ibises breed in groups, building nests on cliff ledges or among rocks on steep slopes. These are usually by the coast or near a river. In Souss-Massa National Park, people have even created extra ledges to help the birds find more nesting spots. Artificial nest boxes are used in the managed group in Birecik. In the past, these birds also nested on buildings.

These ibises start breeding when they are three to five years old, and they stay with the same mate for life. The male chooses a nest spot, cleans it, and then tries to attract a female by waving his crest and making low rumbling sounds. Once a pair forms, they strengthen their bond by bowing to each other and preening each other's feathers.

The nest is loosely built with twigs and lined with grass or straw. A female usually lays two to four eggs. The eggs are blue-white with brown spots and weigh about 50.16 g (1.769 oz). Both parents take turns sitting on the eggs for 24–25 days until they hatch. The chicks leave the nest after 40–50 days and can fly at about two months old. Both parents also feed the chicks.

Northern bald ibises live for about 20 to 25 years in zoos. In the wild, they usually live for 10 to 15 years.

Feeding Habits

These social birds fly in flocks from their nesting cliffs or winter roosts to find food. They often fly in a "V" shape. In winter, these flocks can have up to 100 birds. During breeding season, ibises regularly fly up to 15 km (9.3 mi) from their colony to find food. They prefer dry grasslands that aren't being farmed, but they will also use empty fields.

The northern bald ibis eats many different kinds of animal food. Studies of their droppings in Morocco show that lizards and darkling beetles are a big part of their diet. They also eat small mammals, ground-nesting birds, and insects like snails, scorpions, spiders, and caterpillars. Males sometimes "steal" food from females. As the flock moves, the ibis uses its long beak to feel for food in the soft, sandy soil. Because they hunt by probing, soft ground is very important. The plants in the area should also be sparse and not taller than 15–20 cm (6–8 in).

Protecting the Northern Bald Ibis

Even though the northern bald ibis disappeared from Europe a long time ago, many groups in Morocco and Algeria survived until the early 1900s. But then their numbers started to drop faster. The last group in Algeria disappeared in the late 1980s. In Morocco, there were about 38 groups in 1940, but only 15 by 1975. The last migrating groups in the Atlas Mountains were gone by 1989.

Today, the northern bald ibis is listed as Endangered by the IUCN. In 2018, there were about 147 breeding pairs in the wild and over 1,000 birds in zoos. It used to be Critically Endangered, but strong conservation efforts in Morocco, Turkey, and Europe have helped its numbers grow.

The northern bald ibis is an important bird for the Agreement on the Conservation of African-Eurasian Migratory Waterbirds (AEWA). It has a detailed plan to help it survive. Since it's threatened with extinction, it's also listed on Appendix 1 of CITES. This means that buying or selling these birds (or their parts) for money is against the law.

The northern bald ibis has been declining for centuries, partly due to natural reasons we don't fully understand. But the faster decline in the last 100 years (losing 98% of its population between 1900 and 2002) is due to many things. These include hunting, loss of their dry grassland homes, pesticide poisoning, and human disturbance. For example, three dead adult ibises from the Turkish group were found in Jordan. They had been electrocuted by power lines.

Wild Populations

Morocco's Success Story

Organizations like BirdLife International and RSPB help watch over the wild ibises in Morocco. For the first time, there's proof that the wild population is growing! In the ten years before 2008, the number of breeding pairs in Morocco grew to 100. By 2013, it reached a record 113 breeding pairs.

Simple protection of their nesting and feeding sites has helped them grow. Local community members act as wardens, reducing human disturbance and showing how valuable these birds are. Providing drinking water and keeping predators away also helps them breed. Studies show that dry grasslands and fields left empty for two years are key feeding areas.

In early 2019, the total population in the two main areas of Souss-Massa National Park and Tamri reached 708 birds. In the last breeding season, 147 breeding pairs produced 170 chicks!

Keeping these non-intensive land uses in the future might be a challenge. The recovery in the Souss-Massa area is still fragile because most of the birds are in just a few places. However, this growth could help them spread to other areas further north in Morocco where they used to live.

The main reason for breeding failure in Souss-Massa National Park is that predators, especially common ravens, eat the eggs. The effect of predators on adult birds hasn't been studied much. There's also been some chick starvation in certain years. But the biggest threats to breeding birds are human disturbance and the loss of their feeding grounds. In May 1996, 40 adult ibises died or disappeared in Morocco over nine days. Scientists think it might have been a virus, a toxin, or botulism.

Syria's Challenges

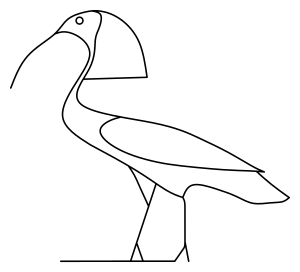

Efforts to save the northern bald ibis in Syria began in 2002 when a hidden group was found in the Palmyra desert. These ibises are the last living relatives of those shown in ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs from 4500 years ago! This discovery was made possible by the knowledge of Bedouin nomads and local hunters.

After the discovery, a successful program was set up in Palmyra from 2002 to 2004 to protect the ibises. Fourteen chicks successfully left their nests during this time. An Ibis Protected Area was created, and education programs were started.

However, two breeding failures happened in 2005 and 2008 due to changes in how the project was managed. Satellite tags showed that only adult birds were reaching their wintering site in Ethiopia. The low survival rate of young birds was causing the group to shrink from 3 breeding pairs in 2002 to just 1 in 2010. Studies in Saudi Arabia suggested that hunting and electrocution from power lines were killing many young ibises.

In 2010, a trial was done to introduce captive-born chicks into the wild group in Palmyra. Three chicks followed a wild adult for over 1,000 km (620 mi) into Saudi Arabia! This success gave hope that the group could still be saved. Unfortunately, conservation efforts stopped in March 2011 because of the political situation in Syria. The last time a lone bird was seen returning to Palmyra was in 2014. By 2015, no birds came back. As of 2017, some birds are still seen at the wintering grounds.

Turkey's Managed Colony

Since the truly wild Turkish population was lost, a new semi-wild group was started at Birecik. These birds are carefully managed. They are kept in cages after the breeding season to stop them from migrating. This program has been successful, with 205 birds by March 2016. The goal is to let them migrate once the population reaches a stable 100 pairs.

The birds are released in late January or early February to breed outside the cages. They fly freely and look for food around Birecik, but they also get extra food. After breeding season, they are put back in cages in late July or early August to prevent migration. A test migration with tagged birds showed the dangers of pesticides to traveling birds. The Syrian Civil War also added another reason to keep them from migrating.

Reintroduction Efforts

Rules for bringing back the northern bald ibis were set in 2003 at a meeting in Innsbruck, Austria. Key decisions included:

- Not adding zoo-bred ibises to the wild groups in Souss-Massa or Palmyra.

- Respecting the two different groups of northern bald ibises (eastern and western).

- Raising chicks by hand with human "parents" to prepare them for release.

- Teaching young birds migration routes, as they likely won't find them on their own.

A second meeting in Spain in 2006 emphasized finding new or old ibis colonies in north-west Africa and the Middle East. It also stressed improving conditions in the Birecik birdhouses and using only birds of known origin for breeding and release programs.

Zoo Populations

There are 850 northern bald ibises in European zoos and another 250 in Japan and North America. European zoos produce 80 to 100 young birds each year. Earlier attempts to release zoo-bred birds were not successful. All northern bald ibises in zoos (except in Turkey) are from the western population, originally from Morocco.

Zoo birds often have skin problems. About 40% of birds that had to be put down suffered from chronic skin issues, with feather loss and sores. The cause of this disease is unknown. Other health problems in zoos include bird tuberculosis and heart issues.

Bringing Them Back to Europe

In 1504, a rule by Archbishop Leonhard of Salzburg made the northern bald ibis one of the world's first officially protected species. They nested on cliffs and castles in Austria but disappeared around 1630–1645. Young birds were hunted as a special food for nobles. Despite the rule, they died out in Austria, just like in other parts of Europe.

Now, there are two ibis reintroduction projects in Austria, at Grünau and Kuchl. A research station at Grünau has a breeding group that flies freely but is caged during migration. This helps scientists study their behavior and how they learn to find food.

The Scharnstein Project tries to create a migrating waldrapp group by using ultralight planes to teach them a migration route. In 2002, 11 birds were trained to follow two small planes. In 2003, they tried to lead a group from Scharnstein to southern Tuscany. Later releases were more successful, with birds spending winter in Tuscany and returning to northern Austria from 2005. In 2008, a female ibis named Aurelia flew 930 km (580 mi) back to Austria for her fourth return! This shows how dangerous the journey can be, as she lost her two young and her mate on the way south in 2007.

In August 2013, the European Union agreed to support reintroduction projects until 2019. The Reason for Hope project, led by Dr. Johannes Fritz, has breeding and observation sites in Austria, Bavaria (Germany), and Baden-Württemberg (Germany). They use light solar transmitters to track the birds' flights. After learning to follow their human foster-mothers in ultralight aircraft, about 30 young birds are led over the Alps to spend winter in Tuscany. In November 2019, the project team successfully helped young birds fly with experienced adults to their wintering site.

Proyecto Eremita is a Spanish reintroduction project that released nearly 30 birds. It had its first success in 2008 when a pair laid two eggs. This was likely the first time they bred in the wild in Spain in 500 years! This project is a team effort by the Andalusian government, the Spanish Ministry of Defence, and the Zoobotánico de Jeréz, with help from scientists and volunteers. The Spanish group has been growing well, from 9 breeding pairs in 2011 to 23 in 2014, raising 25 chicks. In 2014, the total population was 78 wild birds in two groups. By 2022, the wild population near Cádiz had grown to about 180 birds.

In June 2023, a pair was reported nesting on a building near Zurich Airport in Switzerland, with two young. This was the first recorded breeding pair in Switzerland in over 400 years! The adult birds were tracked from the reintroduction project in Überlingen, Germany.

Northern Morocco Reintroduction

There's a plan to reintroduce the ibis at Ain Tijja-Mezguitem in north-east Morocco. Since the wild groups further south are still at risk, the idea is to create a non-migratory population here. These birds would come from zoos in Germany, Switzerland, and Austria. This area was known to have ibises until about 1980. The station in the Rif mountains was built in 2000. In 2006, six pairs bred successfully, raising six chicks. By 2007, there were 19 birds in the aviary.

The mountains have many possible nesting ledges, and an artificial lake provides water. The dry grasslands are good for foraging, as they are not exposed to harmful chemicals. Once the population reaches about 40 birds, they will be released. This site is far from the wild groups in Agadir, so there's little risk of mixing the populations by accident.

Northern Bald Ibises in Culture

In the Birecik area of Turkey, local stories say the northern bald ibis was one of the first birds Noah released from the Ark. It was seen as a symbol of new life. This religious belief helped the groups there survive long after they disappeared from Europe.

In Ancient Egypt, this ibis was seen as a holy bird, a symbol of brightness and glory. Along with the sacred ibis, it was thought to be a form of Thoth, the god of writing. The ancient Egyptian word akh, meaning "to shine," was shown in hieroglyphs by a bald ibis, probably because of its shiny feathers. Akh also meant excellence, glory, and even the soul or spirit.

The ancient Greek writer Herodotus wrote about the man-eating Stymphalian birds. These mythical birds had brass wings and sharp metal feathers they could shoot at people. One of Heracles's tasks was to get rid of them from Lake Stymphalia. Some people think these mythical birds were based on the northern bald ibis. However, they were described as marsh birds and usually shown without crests, so they were more likely based on the sacred ibis.

The bird painted in 1490 in a Gothic fresco in the Holy Trinity Church, Hrastovlje (now in Slovenia) was most likely the northern bald ibis. Small drawings of this bird are also found in old manuscripts and paintings from the 1500s. It's believed they were native to parts of Slovenia and Croatia during the Middle Ages.

In Birecik, Turkey, an old celebration called 'Kelaynak yortusu' was held in mid-February to mark the birds' return from Africa. This festival was brought back in the 1950s.

Several countries have put the northern bald ibis on their postage stamps. These include Algeria, Morocco, Sudan, Syria, Turkey, and Yemen (where they live or migrate). Austria, which is trying to reintroduce the bird, and Jersey, which has a small group in captivity, have also featured it on stamps.