Pearl incident facts for kids

The Pearl incident was the biggest recorded attempt by enslaved people to escape without violence in United States history. On April 15, 1848, seventy-seven enslaved people tried to escape Washington D.C. They planned to sail away on a ship called The Pearl. Their goal was to sail south on the Potomac River, then north up the Chesapeake Bay and Delaware River. They hoped to reach the free state of New Jersey, a journey of about 225 miles (362 km).

People who wanted to end slavery, called abolitionists, helped organize this escape. Both white and free Black people were involved. Paul Jennings, a formerly enslaved man who had worked for President James Madison, helped plan the escape.

The escapees included men, women, and children. Strong winds against the ship delayed their journey. Two days later, an armed group caught them on the Chesapeake Bay near Point Lookout, Maryland. As punishment, the owners sold most of the captured people to traders. These traders took them to the Deep South, where slavery was often harsher.

However, the freedom of two sisters, Mary and Emily Edmonson, was bought that same year. Funds were raised by Henry Ward Beecher's church in Brooklyn, New York.

When the ship and its captives were brought back to Washington, a riot broke out. People who supported slavery tried to attack an abolitionist newspaper and other anti-slavery activists. Police patrolled for three days to control the violence. This event caused a big debate about slavery in Congress. It may have influenced a part of the Compromise of 1850. This agreement ended the slave trade in Washington D.C., but not slavery itself. The escape also inspired Harriet Beecher Stowe to write her famous novel Uncle Tom's Cabin (1852). In the book, enslaved people greatly feared being "sold South." The incident also increased support for ending slavery in the North.

Three white men were first charged with helping the escape. The ship captains, Daniel Drayton and Edward Sayres, were found guilty in 1848. After spending four years in prison, President Millard Fillmore pardoned them in 1852.

Contents

Why the Escape Happened

Washington, D.C., was a major center for the slave trade in the South. Many families in the city enslaved people, forcing them to work as house servants or skilled workers. Some owners also hired out their enslaved people to work in the city.

By 1848, there were three times more free Black people than enslaved people in Washington D.C. Abolitionists, both Black and white, were actively working to end the slave trade and slavery in the city. Since the 1840s, there was also an organized group that supported the Underground Railroad in the area. The abolitionist community planned the escape to draw attention to slavery in Washington D.C. They hoped to get Congress and the country to act.

White supporters included William L. Chaplin and Gerrit Smith from New York. They helped find Captain Daniel Drayton and pay for the ship. The Black community also played a big role. They told so many families about the plan that 77 enslaved people wanted to join the escape.

Just before the escape, many people in Washington D.C. were celebrating news from France. The French king had been removed, and a new republic was formed, promising human rights and freedom. Some free Black people and enslaved people were inspired by this news. They hoped for similar freedoms for American slaves. People gathered in Lafayette Square in front of the White House to hear speeches.

In April 1848, Daniel Bell, a blacksmith at the Washington Navy Yard and a formerly enslaved man, helped plan the escape. Daniel Bell worried that his wife Mary and their children would be sold after their owner died. The Bell family had tried many times to gain their freedom through the courts, but failed. Ultimately, Daniel's wife Mary, eight of their children, and two grandchildren risked the dangerous journey on the schooner Pearl. Paul Jennings, a formerly enslaved man of President James Madison, was also among the free Black organizers.

Among the enslaved people planning to leave were six adult brothers and sisters from the Paul and Amelia Edmonson family. Because Amelia was enslaved, her fourteen children were born into slavery. Paul Edmonson was a free Black man. The two sisters and four brothers had been "hired out" by their owner to work for pay in the city. Many other families also hoped to escape.

The Potomac River and Chesapeake Bay offered a water route to the free states of New Jersey and Pennsylvania. But the organizers needed a ship to carry the enslaved people over 225 miles (362 km) of water. Jennings later wrote a letter to Senator Daniel Webster, an abolitionist, admitting his role in organizing the escape. Jennings managed to avoid public attention for his part at the time.

Daniel Drayton, the captain chosen to pilot the ship, was from Philadelphia and supported ending slavery. He admitted he was offered money to transport the enslaved people. He found a ship and a partner, Edward Sayres, who was the pilot of the 54-ton schooner The Pearl. Their only other crew member was Chester English, the cook. On Saturday night, April 15, seventy-seven Black men, women, and children quietly boarded the ship. Drayton and Sayres took the risk of transporting them. Chester English, the cook, was on The Pearl to provide food for the passengers until they reached freedom.

The Escape and Capture

The plan was for the ship to sail 100 miles (160 km) down the Potomac River. Then, it would go 125 miles (201 km) north up the Chesapeake Bay to freedom in New Jersey. But the wind was blowing against the schooner, so the ship had to stop and anchor for the night.

The next morning, many slave owners realized their enslaved people were missing. They quickly sent out an armed group of 35 men on a steamboat called The Salem.

Captain Drayton later described how The Pearl was captured:

A Mr. Dodge, of Georgetown, a wealthy old gentleman, originally from New England, missed three or four slaves from his family, and a small steamboat, of which he was the proprietor, was readily obtained. Thirty-five men, including a son or two of old Dodge, and several of those whose slaves were missing, volunteered to man her; and they set out about Sunday noon.

The group on The Salem found The Pearl on Monday morning near Point Lookout in Maryland. They immediately took the enslaved people and the ship back to Washington.

The Betrayal

In 1916, the writer John H. Paynter identified Judson Diggs as the person who betrayed the escapees. Diggs drove one participant to the dock and was promised future payment. However, Diggs then reported the suspicious activity. Paynter, who was a descendant of the Edmonson siblings, interviewed descendants of the escapees. He wrote that Judson Diggs, "one of their own people," acted like a "Judas."

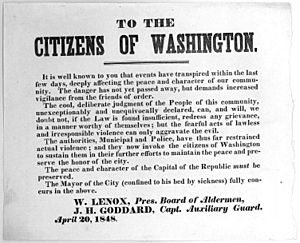

The Riots

People who supported slavery were very angry about the escape attempt. An angry crowd formed. For three days, mobs caused trouble in the Washington Riot. Many police officers were called to protect one of their targets. The mob focused on Gamaliel Bailey, who published the anti-slavery newspaper New Era. They suspected him because he had published abolitionist writings. A mob of slave owners almost destroyed the newspaper building, but the police stopped them.

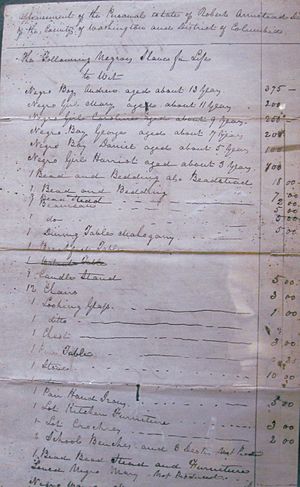

Once the mob calmed down, the slave owners discussed how to punish their enslaved people. They sold all seventy-seven enslaved people to slave traders from Georgia and Louisiana. These traders would take them to the Deep South and the New Orleans slave market. There, they would likely be sold to work on large sugar and cotton farms. By the time of the Civil War, these farms held two-thirds of the enslaved people in the South.

Congressman John I. Slingerland, an abolitionist from New York, told anti-slavery activists about what the slave owners and traders were doing. This helped increase efforts to end the slave trade in the nation's capital. Friends and families rushed to find their loved ones and buy them from the traders before they were taken south. The case of the two young Edmonson sisters especially caught national attention.

The Trial

Drayton, Sayres, and English were first accused of crimes. The educator Horace Mann, who had helped the enslaved people from the La Amistad ship in 1839, was hired as their main lawyer. The following July, both Drayton and Sayres were charged with 77 counts each. These charges were for helping enslaved people escape and illegally transporting them. English was released because his role was small and indirect.

After appeals were made and some charges were lowered, a jury found both Drayton and Sayres guilty. They were sent to jail because neither could pay the fines and court costs, which added up to $10,000. After they had been in prison for four years, Senator Charles Sumner, an abolitionist, asked President Millard Fillmore to pardon them. The President pardoned them in 1852.

What Happened Next

Because of the escape attempt and the riot, Congress ended the slave trade in Washington, D.C. However, they did not end slavery itself. Stopping the slave trade was part of the Compromise of 1850. This agreement mainly dealt with whether new states in the West would allow slavery or be free states. Daniel Bell, even though he was an organizer, was not on The Pearl when it was captured. He may have been questioned, but he was lucky because he was never charged with helping the plot. He was able to keep his job at the navy yard, though his pay was lowered.

The failed escape attempt caused strong reactions from both abolitionists and pro-slavery activists across the country. It added to the heated arguments that eventually led to the American Civil War. It also inspired Harriet Beecher Stowe to write her very popular anti-slavery novel, Uncle Tom's Cabin, published in 1852.

In 2017, a street in The Wharf area of Washington, D.C. was named "Pearl Street." This was done to remember the incident.

See also

- Robert Smalls, who led a group of escapees through a blockade using the USS Planter in 1863

| Delilah Pierce |

| Gordon Parks |

| Augusta Savage |

| Charles Ethan Porter |