Edmonson sisters facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Edmonson sisters

|

|

|---|---|

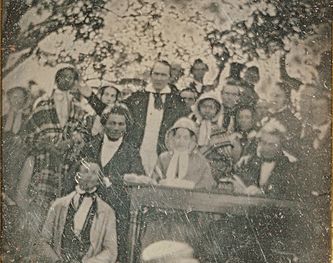

Daguerreotype of Mary (standing) and Emily Edmonson (seated), shortly after they were freed in 1848

|

|

| Occupation | Abolitionists |

| Known for |

|

| Mary Edmonson | |

| Born | 1832 Montgomery County, Maryland, US |

| Died | 1853 (aged 20–21) Oberlin College, Oberlin, Ohio, US |

| Emily Edmonson | |

| Born | 1835 Montgomery County, Maryland, US |

| Died | September 15, 1895 (aged 59–60) Washington, D.C., US |

| Spouse(s) |

Larkin Johnson

(m. 1860) |

Mary Edmonson (1832–1853) and Emily Edmonson (1835–September 15, 1895) were two young African American women. They became well-known figures in the movement to end slavery in the United States.

On April 15, 1848, they were among 77 enslaved people. They tried to escape from Washington, D.C. on a boat called the schooner The Pearl. Their plan was to sail up the Chesapeake Bay to freedom in New Jersey.

Even though their escape failed, they were later freed. Funds were raised by the Congregational Plymouth Church in Brooklyn, New York. Their pastor, Henry Ward Beecher, was a famous abolitionist. After gaining freedom, the Edmonson sisters went to school and worked. They also traveled with Beecher, speaking out against slavery across the Northern states.

Contents

Early Life and Family

The Edmonson sisters were the daughters of Paul and Amelia Edmonson. Paul was a free black man, but Amelia was enslaved in Montgomery County, Maryland. Mary and Emily were two of 13 or 14 children who lived to be adults. All of them were born into slavery.

Laws in slave states said that if your mother was enslaved, you were also born into slavery. This was called partus sequitur ventrem.

Their father, Paul Edmonson, was set free by his owner's will. Maryland had many free black people. Most of them were freed after the American Revolution. Slave owners were encouraged to free enslaved people by the ideas of the war. Quaker and Methodist preachers also encouraged it.

Paul Edmonson bought land in the Norbeck area of Montgomery County. He farmed there and raised his family. Amelia was allowed to live with her husband, but she still worked for her enslaver.

The children started working at a young age. They worked as servants, laborers, and skilled workers. From about age 13 or 14, they were "hired out" to work in rich homes in nearby Washington, D.C.. This meant their wages went to their enslaver.

By 1848, four of the older Edmonson sisters had bought their freedom. Their husbands and family helped them. But their enslaver decided not to let any more siblings buy their freedom. Six of the siblings, including Mary and Emily, were hired out for his benefit.

The Escape Attempt

On April 15, 1848, a boat called the Pearl arrived at a dock in Washington. The Edmonson sisters and four of their brothers joined 77 enslaved people. They planned to escape on the Pearl to freedom in New Jersey.

Two white abolitionists, William L. Chaplin and Gerrit Smith, helped plan the escape. Two free black men in Washington, including Paul Jennings, also helped. The escape started as a small plan for seven enslaved people. But it grew into a large, organized effort among the free and enslaved black communities. The white organizers and crew did not know how big it had become.

In 1848, there were three times more free black people than enslaved people in Washington, D.C. This showed the community could work together. Seventy-seven enslaved people boarded the Pearl. The boat was to sail down the Potomac River and up the Chesapeake Bay. Then it would go through the Chesapeake & Delaware Canal and up the Delaware River to New Jersey. This was a journey of 225 miles. At the time, Emily was 13 years old, and Mary was 15 or 16.

The Pearl began its journey down the Potomac with the people hidden among boxes. It was delayed overnight by the changing tides. Then it had to wait out bad weather while anchored in the bay.

In Washington, the alarm was raised the next morning. Many enslavers found their enslaved people had escaped. Enslavers formed an armed group that went downriver on a steamboat. The steamboat caught the Pearl at Point Lookout, Maryland. The group seized the boat and towed it back to Washington, D.C.

When the Pearl arrived in Washington, an angry crowd was waiting. The two white captains, Daniel Drayton and Edward Sayres, had to be taken to safety. Pro-slavery people attacked them. The escaped enslaved people were taken to a local jail. It was reported that someone asked the Edmonson girls if they were ashamed. Emily proudly replied that they would do the same thing again.

Three days of riots followed. Pro-slavery people attacked anti-slavery offices and printing presses. They tried to stop the abolitionist movement. Most enslavers of the escaped people quickly sold them to slave traders. They did not want to give them another chance to escape. Fifty of the enslaved people were sent by train to Baltimore. From there, they were sold and sent to the Deep South.

Journey to New Orleans

Paul Edmonson tried hard to delay the sale of his children. He wanted to raise enough money to buy their freedom. But the slave traders Bruin & Hill from Alexandria, Virginia, bought the six Edmonson siblings.

The siblings were transported by ship to New Orleans. Conditions were very harsh. In New Orleans, they were offered for a very high price—$1,200 each. New Orleans was the biggest slave market in the country then.

Hamilton Edmonson, the oldest of the siblings, had been living as a free man for several years. He worked as a cooper, making barrels. Their father arranged for donations from a Methodist minister. With this help, Hamilton arranged for his brother Samuel Edmonson to be bought by a rich New Orleans cotton merchant. Samuel worked as his butler. When the merchant died in 1853, Samuel moved with that family to what is now the 1850 House in the Pontalba Buildings.

In New Orleans, the other siblings had to stay for days on an open porch facing the street. They waited for buyers. The sisters were treated roughly. Before the family could rescue them, a serious illness spread in New Orleans. The slave traders took the Edmonson sisters back to Alexandria. They did this to protect their investment.

Ephraim Edmonson and John Edmonson, two other brothers who tried to escape on the Pearl, stayed in New Orleans. Their brother Hamilton worked to earn money and eventually bought their freedom.

Henry Ward Beecher's Help

In Alexandria, the Edmonson sisters were hired out to do laundering, ironing, and sewing. Their wages went to the slave traders. They were locked up at night. Paul Edmonson kept trying to free his daughters. Bruin & Hill demanded $2,250 for their release.

Paul Edmonson met Henry Ward Beecher. Beecher was a young Congregationalist preacher in Brooklyn, New York. He was known for supporting abolitionism. Paul had letters from supporters in the Washington area.

Beecher's church members raised the money to buy the Edmonson sisters and set them free. Beecher went to Washington with William L. Chaplin, a white abolitionist who had helped pay for the Pearl. They arranged the purchase.

Mary Edmonson and Emily Edmonson became free on November 4, 1848. The family gathered for a celebration at another sister's house in Washington. Beecher's church kept giving money to send the sisters to school. They first went to New York Central College, a school for both black and white students in Cortland County, New York. They also worked as cleaning servants to support themselves.

While studying, the sisters took part in anti-slavery meetings around New York state. Their story of slavery, escape, and suffering was often told. Beecher's son wrote that "this case at the time attracted wide attention."

At these meetings, the Edmonson sisters took part in mock slave auctions. Beecher designed these to get attention for the abolitionist cause.

Speaking Out Against Slavery

In summer 1850, the Edmonson sisters attended the Fugitive Slave Convention. This was an anti-slavery meeting in Cazenovia, New York. Local abolitionist Theodore Dwight Weld and others organized it. They wanted to protest against the Fugitive Slave Act. This act was soon to be passed by the U.S. Congress. Under this law, enslavers could arrest people who had escaped slavery, even in the North.

At this meeting, the sisters were in a famous daguerreotype photograph. It was taken by Theodore Dwight Weld's brother, Ezra Greenleaf Weld. The famous speaker Frederick Douglass was also in the picture.

The Edmonson sisters' light skin color may have made them good "public faces" for American slavery. They helped show people what slavery was like.

Education and Later Life

In 1853, the Edmonson sisters went to the Young Ladies Preparatory School at Oberlin College in Ohio. Beecher and his sister, Harriet Beecher Stowe, helped them. Stowe was the author of Uncle Tom's Cabin. Oberlin College had accepted black and white students since the 1830s. It was a center for abolitionist work. Six months after arriving at Oberlin, Mary Edmonson died of tuberculosis.

That same year, Stowe included parts of the Edmonson sisters' story in her book A Key to Uncle Tom's Cabin. This book shared true stories of slavery.

Eighteen-year-old Emily returned to Washington with her father. She enrolled in the Normal School for Colored Girls. This school (now the University of the District of Columbia) trained young African American women to become teachers. For safety, the Edmonson family moved to a cabin on the school grounds. Emily and Myrtilla Miner, the school's founder, learned to shoot. Emily taught black women and continued her work against slavery.

At age 25 in 1860, Emily Edmonson married Larkin Johnson. They lived in the Sandy Spring, Maryland area for twelve years. Then they moved to Anacostia in Washington, D.C. There, they bought land and helped start the Hillsdale community.

Emily kept her friendship with Frederick Douglass, who also lived in Anacostia. Both continued working in the abolitionist movement. Even after slavery was ended by the 13th Amendment, they remained very close. Emily's granddaughters said they were like "brother and sister." Emily Edmonson Johnson died at her home on September 15, 1895.

Legacy and Honors

- In 2010, the city of Alexandria, Virginia, named a park on Duke Street Edmonson Plaza. It is named after the two sisters. The park is near a former slave trader's building and other historical sites related to slavery.

- Also in 2010, a 10-foot-tall bronze sculpture of the two sisters was put in Edmonson Plaza. The sculptor was Erik Blome. It is next to the building that was Bruin & Hill's slave-holding facility.

Other Representation

- In 1992, Judlyne A. Lilly's play The Pearl was first performed. It was based on writings by John H. Paynter, a descendant of one of the Pearl escapees. The play was shown by The Source Theatre in Washington, D.C.

See also

In Spanish: Hermanas Edmonson para niños

In Spanish: Hermanas Edmonson para niños

- Fugitive slave laws

- List of slaves

| Frances Mary Albrier |

| Whitney Young |

| Muhammad Ali |