Peter Martyr Vermigli facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

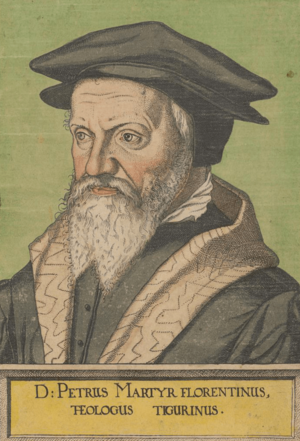

Peter Martyr Vermigli

|

|

|---|---|

| Pietro Martire Vermigli | |

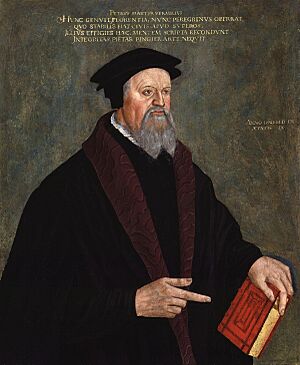

Pietro Vermigli, by Hans Asper, 1560

|

|

| Born |

Piero Mariano Vermigli

8 September 1499 Florence, Florentine Republic, Holy Roman Empire

|

| Died | 12 November 1562 (aged 63) Zürich, Canton of Zürich, Swiss Confederacy

|

| Nationality | Italian |

| Alma mater | University of Padua |

| Ordination | 1525 |

| Theological work | |

| Era | Reformation |

| Tradition or movement | Reformed tradition |

| Notable ideas | Defense of the Reformed doctrine of the Eucharist |

Peter Martyr Vermigli (born Piero Mariano Vermigli, 8 September 1499 – 12 November 1562) was an important Reformation leader. He was born in Italy but later became a key figure in the Protestant movement in Europe. His ideas helped shape the Church of England and influenced many other people to become Protestants.

Vermigli was known for his strong beliefs about the Eucharist (also called Holy Communion), which is a special Christian ceremony. He wrote many books and debated with others about this topic. His writings were collected into a famous textbook called Loci Communes, which was used by many students studying theology.

Contents

Peter Martyr Vermigli: A Reformation Hero

Vermigli was born in Florence, Italy. He became a monk and was given important jobs as an abbot and prior. He met other leaders who wanted to reform the Catholic Church. He also read books by Protestant thinkers like Martin Bucer and Ulrich Zwingli.

By studying the Bible and early Christian writings, Vermigli started to believe in Protestant ideas. He believed that people are saved by faith alone, not by good deeds. He also had different ideas about the Eucharist. To follow his beliefs and avoid being punished by the Roman Inquisition, he left Italy.

He went to Strasbourg (now in France) where he taught about the Old Testament part of the Bible. Later, he was invited to Oxford University in England. There, he continued teaching and defended his views on the Eucharist in public debates. When a Catholic queen came to power in England, Vermigli had to leave. He returned to Strasbourg and then moved to Zürich, Switzerland, where he taught until he died in 1562.

Early Life and Studies (1499–1525)

Peter Martyr Vermigli was born in Florence on September 8, 1499. His father was a rich shoemaker. Peter was the oldest of three children. His mother taught him Latin when he was young. She died when he was twelve.

From a young age, Peter wanted to become a Catholic priest. In 1514, he joined a monastery called the Badia Fiesolana. Monks there focused on strict rules and serving people in cities. In 1518, he took the name Peter Martyr.

He was sent to study at a monastery in Padua, Italy. This monastery was connected to the famous University of Padua. There, Vermigli learned about Aristotle and Christian thinkers like Augustine. He taught himself Ancient Greek so he could read Aristotle in its original language. He also met other important thinkers who wanted to reform the church.

Early Italian Ministry (1525–1541)

Vermigli became a priest in 1525. He started preaching in 1526 and traveled around Italy for three years. He also gave lectures on the Bible.

In 1530, he was put in charge of a monastery in Bologna. There, he learned Hebrew from a Jewish doctor. This allowed him to read the Old Testament in its original language. This was unusual for priests at the time.

In 1533, Vermigli became the abbot of two monasteries in Spoleto. The monasteries had been very relaxed before he arrived. Vermigli brought order back to them and improved their relationship with the local bishop. He was re-elected as abbot in 1534 and 1535. He also helped with efforts to reform the Catholic Church.

In 1537, Vermigli became abbot of a monastery in Naples. There, he met Juan de Valdés, a leader of a reform group. Valdés introduced Vermigli to the writings of Protestant reformers. Vermigli slowly started to accept Protestant ideas, especially about salvation by faith alone. He also began to question the traditional Catholic view of the sacraments.

In 1539, Vermigli preached about a Bible passage that was often used to support the idea of purgatory. He did not agree with this view in his sermon. This caused some controversy, and his preaching was briefly stopped. However, he appealed to Rome and was allowed to continue.

In 1541, Vermigli became the prior of Basilica of San Frediano in Lucca. This was an important job. The monks and clergy in Lucca were known for being lazy. Vermigli wanted to educate them and improve their behavior. He started a college that taught Greek, Latin, and Hebrew. Many of the teachers there later became Protestants.

Leaving Italy and Teaching in Strasbourg (1542–1547)

Vermigli was respected and careful, so he was able to continue his reforms in Lucca without being suspected of having unusual views. However, some of his followers openly questioned the Pope's authority. This led to problems. The Roman Inquisition was restarted in 1542, and Lucca was seen as a place where Protestants were welcome. The city leaders worried about losing their independence.

Vermigli was called to a special meeting, but his friends warned him of danger. He decided to leave Italy on August 12, 1542. He went to Pisa, where he celebrated a Protestant version of the Eucharist for the first time. He also convinced another popular preacher, Bernardino Ochino, to flee Italy with him. Vermigli then traveled to Zürich.

In Zürich, Protestant leaders questioned Vermigli about his beliefs. They decided he could teach Protestant theology. He then moved to Strasbourg and became a close friend of Martin Bucer. Vermigli took over Bucer's teaching position, lecturing on the Old Testament. He was popular with his students because he was clear and precise. Many of his students could read Hebrew, which he enjoyed.

In 1545, Vermigli married his first wife, Catherine Dammartin. She was a former nun.

Influence in England (1547–1553)

When Edward VI became king of England in 1547, Protestant reformers hoped to change the Church of England even more. Archbishop Thomas Cranmer invited Vermigli and Ochino to help. Vermigli accepted and sailed to England. In 1548, he became a very important professor at Oxford University.

At Oxford, Vermigli lectured on the Bible. He spoke against Catholic ideas like purgatory and priests not being allowed to marry. He also spoke against the Catholic view of the Eucharist, which was a big debate at the time. Some Catholic professors challenged Vermigli to a public debate. Vermigli defended his views against them. This debate made him a leading voice in the discussions about the Eucharist.

In 1549, there were uprisings in England against the new Protestant prayer book. Vermigli had to leave Oxford for a short time. He helped Archbishop Cranmer write sermons against the rebellion. When he returned to Oxford, he became a leader at Christ Church. Vermigli was the first married priest at Oxford, and his wife caused some controversy.

Vermigli became very involved in English church matters. He helped Cranmer make changes to the Book of Common Prayer, which was the official prayer book of the Church of England. He also helped write new church laws.

When the Catholic Queen Mary came to power in 1553, Vermigli was put under house arrest. His Catholic opponents wanted him executed. However, he was able to get permission to leave England.

Vermigli's wife, Catherine, had died earlier that year. She was known for her kindness. After Vermigli left, her body was dug up and thrown away by Catholic opponents. Later, when the Protestant Queen Elizabeth came to power, Catherine's body was reburied with honor.

Return to Strasbourg and Zürich (1553–1562)

Vermigli arrived back in Strasbourg in October 1553. He got his old teaching job back. He often met with other Protestants who had fled England. He lectured on the Bible, and his lectures often talked about political issues like whether people had the right to resist a bad ruler.

Strasbourg had become more Lutheran since Vermigli left. Vermigli had some disagreements with the Lutherans there, especially about the Eucharist and predestination (the idea that God has already chosen who will be saved). Because of these disagreements, he accepted an offer to teach in Zürich, Switzerland, in 1556.

In Zürich, Vermigli became the head of Hebrew studies. He married his second wife, Catarina Merenda, in 1559. He was able to publish many of his lecture notes. He turned down offers for jobs in other cities, choosing to stay in Zürich.

Vermigli's ideas about the Eucharist were accepted in Zürich. However, he faced controversy over his strong belief in predestination. He believed that God chooses some people for salvation and others are not chosen. Another professor, Theodor Bibliander, disagreed strongly with Vermigli. Bibliander believed that God only chooses to save those who believe in Him. The church in Zürich supported Vermigli's view, and Bibliander was dismissed.

In 1561, Vermigli attended a meeting in France called the Colloquy at Poissy. This meeting tried to bring Catholics and Protestants together. Vermigli gave a speech about the Eucharist, explaining that Jesus' words "this is my body" were symbolic, not literal.

Vermigli's health was getting worse. He died on November 12, 1562, in Zürich from a fever. He was buried in the Grossmünster cathedral. He had two children with his second wife, but they died young. Four months after his death, his wife had their third child, Maria.

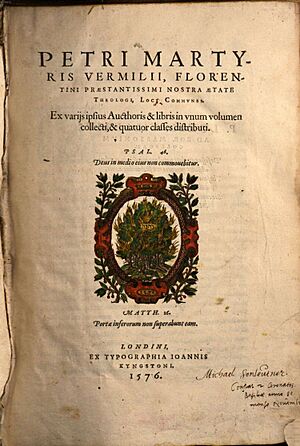

Important Works

Vermigli is most famous for his Loci Communes (which means "commonplaces" in Latin). This book is a collection of his teachings on different topics, taken from his Bible commentaries. It was published in 1576, after his death. It became a very popular textbook for Protestants.

During his lifetime, Vermigli published commentaries on several books of the Bible, including 1 Corinthians, Romans, and Judges. He was known for studying the original Hebrew and Greek texts of the Bible. He also knew a lot about ancient Jewish writings, more than many other scholars of his time.

Vermigli also wrote important books defending his views on the Eucharist. He strongly disagreed with the Catholic idea of transubstantiation, which says that the bread and wine in the Eucharist literally change into Christ's body and blood. He argued that the Bible did not support this idea. His writings influenced the changes made to the English Book of Common Prayer in 1552.

He also debated with Lutherans who believed that Christ's body was everywhere, and therefore physically present in the Eucharist. Vermigli argued that Christ's body stays in Heaven.

Vermigli's Ideas

Vermigli was mainly a Bible teacher, but his ideas about the Eucharist had a lasting impact. He believed that the Bible was the highest authority for truth. However, he also knew a lot about the writings of early Christian leaders. He used their ideas to support his own interpretations of the Bible.

Vermigli is best known for arguing against transubstantiation. He believed that the bread and wine in the Eucharist do not change into Christ's body and blood. Instead, he taught that Christ is offered to those who take part in the Eucharist, and believers receive him spiritually. He also disagreed with those who thought the Eucharist was just a symbol.

Vermigli also developed strong ideas about predestination. He believed that God is in control of everything. He thought that God chooses some people for salvation based on His grace (undeserved favor). He also believed that God allows others to remain in their sinful state. Vermigli's ideas on predestination were similar to, but slightly different from, those of John Calvin, another famous reformer.

Vermigli's writings often talked about political issues. He believed that rulers should promote good behavior, including religion. He supported the idea of royal supremacy in England. This meant that the king, if he obeyed God, had the right to rule the church in his land. Vermigli believed that the king's power was over outward matters of society, not over people's inner spiritual beliefs. His ideas helped shape the religious changes made in England under Queen Elizabeth I.

Lasting Impact

Vermigli's leadership in Lucca made it one of the most Protestant cities in Italy. When the Inquisition started, many Protestants from Lucca fled to Geneva, creating a large group of refugees. Important Reformation leaders like Girolamo Zanchi were influenced by Vermigli.

Many scholars now believe that Vermigli, along with Wolfgang Musculus and Heinrich Bullinger, were just as important as Calvin and Zwingli in shaping the early Protestant movement. Vermigli helped bridge the gap between the first reformers and later Protestant thinkers. He was one of the first to use a more organized, scholarly way of thinking about theology.

Vermigli had a big impact on the English Reformation through his friendship with Archbishop Thomas Cranmer. Vermigli convinced Cranmer to adopt a more Reformed view of the Eucharist. This changed the direction of the English Reformation, as Cranmer was in charge of revising the Book of Common Prayer. Vermigli's ideas were very influential in Oxford and Cambridge during Queen Elizabeth's reign.

Vermigli's writings were printed about 110 times between 1550 and 1650. His Loci Communes became a standard textbook. His works were very popular with English readers in the 1600s. Even John Milton, who wrote Paradise Lost, may have used Vermigli's commentary on Genesis. Vermigli's books were also important textbooks at Harvard College in America.

|