Huldrych Zwingli facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Huldrych Zwingli

|

|

|---|---|

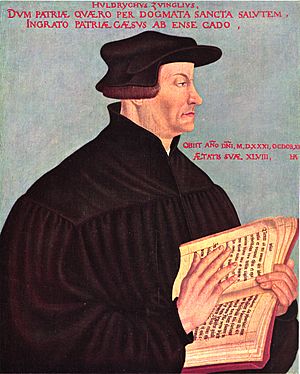

Huldrych Zwingli as depicted by Hans Asper in an oil portrait from 1531 (Kunstmuseum Winterthur)

|

|

| Born | 1 January 1484 Wildhaus, Swiss Confederation

|

| Died | 11 October 1531 (aged 47) Kappel, Canton of Zürich, Swiss Confederation

|

| Education | University of Vienna University of Basel |

| Occupation | Pastor, theologian |

| Spouse(s) | Anna Reinhard |

| Theological work | |

| Era | Renaissance |

| Tradition or movement |

|

| Main interests | |

| Notable ideas |

|

Huldrych Zwingli (born January 1, 1484 – died October 11, 1531) was a key leader in the Reformation in Switzerland. He was born when Swiss people were feeling more patriotic. There was also growing criticism of the Swiss mercenary system. Zwingli studied at the University of Vienna and the University of Basel. Basel was a major center for Renaissance humanism, a movement focused on human values and achievements. He continued his studies while working as a pastor in Glarus and later in Einsiedeln. There, he was greatly influenced by the writings of Erasmus, a famous scholar.

In 1519, Zwingli became the main priest of the Grossmünster church in Zürich. He started to preach new ideas about reforming the Catholic Church. His first public disagreement happened in 1522. He spoke out against the tradition of fasting during Lent. In his writings, he pointed out corruption in the church leadership. He also supported priests being allowed to marry. Zwingli attacked the use of images in churches. One of his most important contributions to the Reformation was his way of preaching. Starting in 1519, he preached through the entire Gospel of Matthew. He then used exegesis (careful study of the Bible) to go through the whole New Testament. This was a big change from the traditional Catholic Mass. In 1525, he introduced a new way to celebrate communion. He also had disagreements with the Anabaptists, which led to them being treated harshly. Historians still discuss if he turned Zürich into a theocracy, a government ruled by religious leaders.

The Reformation spread to other parts of Switzerland. However, some cantons (states) wanted to stay Catholic. Zwingli formed an alliance of Reformed cantons. This split Switzerland along religious lines. In 1529, a war between the two sides was almost avoided at the last minute. Meanwhile, Zwingli's ideas caught the attention of Martin Luther and other reformers. They met at the Marburg Colloquy. They agreed on many religious points. But they could not agree on the idea of the Real Presence of Christ in the Eucharist (communion bread and wine).

In 1531, Zwingli's alliance tried to block food from reaching the Catholic cantons. This was not successful. The Catholic cantons then attacked Zürich when it was not ready. Zwingli died on the battlefield. His ideas and work still influence the Reformed churches today.

Contents

- Swiss History and Zwingli's Time

- Zwingli's Life Journey

- Early Years and Education (1484–1518)

- Becoming a Priest and Political Involvement

- Focus on Study and Move to Zürich

- Zürich Ministry Begins (1519–1521)

- Early Conflicts (1522–1524)

- Zürich Debates (1523)

- Reformation in Zürich (1524–1525)

- Conflict with the Anabaptists (1525–1527)

- Reformation Across Switzerland (1526–1528)

- First Kappel War (1529)

- Marburg Colloquy (1529)

- Politics, Beliefs, and Death (1529–1531)

- Zwingli's Beliefs

- Music in Zwingli's Life

- Zwingli's Lasting Impact

- Images for kids

- See also

Swiss History and Zwingli's Time

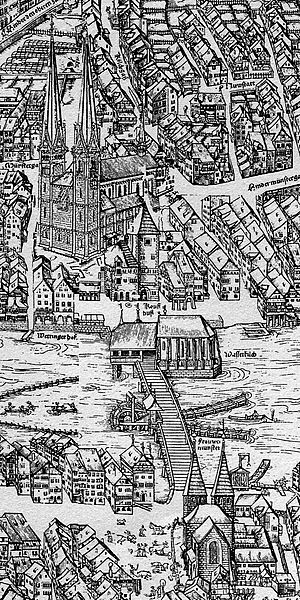

Understanding Switzerland in the 1500s

During Huldrych Zwingli's time, Switzerland was a group of thirteen states called cantons. It also included other connected areas. Unlike modern Switzerland, each canton was almost independent. They handled their own local and international matters. Each canton also made its own alliances. This independence caused conflicts during the Reformation. Different cantons chose different religions. Military goals also grew stronger. Cantons competed to gain new land and resources. An example is the Old Zürich War from 1440–1446.

Europe's Political Climate and Swiss Mercenaries

The political situation in Europe during the 15th and 16th centuries was also unstable. For hundreds of years, Switzerland's foreign policy was shaped by its powerful neighbor, France. Switzerland was technically part of the Holy Roman Empire. But after a series of wars, like the Swabian War in 1499, Switzerland became truly independent. Powerful countries like France and smaller states like the Duchy of Milan fought each other. This had big effects on Switzerland's politics, economy, and society.

During this time, the system of Swiss mercenaries became a big debate. Mercenaries were young Swiss men who fought in foreign wars. They were paid by other countries, which made the cantonal leaders rich. Religious groups in Zwingli's time argued strongly about whether this was right.

Rise of Swiss Identity and Humanism

These internal and external factors helped create a Swiss national identity. The word fatherland started to mean more than just one canton. At the same time, Renaissance humanism became popular in Switzerland. Humanism focused on universal values and learning. Erasmus, a famous scholar, was a great example of this movement. Zwingli was born in 1484 into this world of Swiss patriotism and humanism.

Zwingli's Life Journey

Early Years and Education (1484–1518)

Huldrych Zwingli was born on January 1, 1484, in Wildhaus, Switzerland. He was the third of eleven children in a farming family. His father, Ulrich, was a local leader. Zwingli's first teacher was his uncle, Bartholomew, a church leader. At age ten, Zwingli went to Basel for high school. He learned Latin there. After three years, he spent a short time in Bern with a humanist named Henry Wölfflin. Some monks in Bern tried to get Zwingli to join their order.

However, his father and uncle did not approve. Zwingli left Bern without finishing his Latin studies. He enrolled at the University of Vienna in 1498. He was expelled, but it's not clear why. He re-enrolled in 1500. Zwingli studied in Vienna until 1502. Then he moved to the University of Basel. He earned his Master of Arts degree in 1506.

Becoming a Priest and Political Involvement

Zwingli became a priest in Constance. He held his first Mass in his hometown, Wildhaus, on September 29, 1506. As a young priest, he had not studied much theology. This was common at the time. His first church job was as a pastor in Glarus, where he stayed for ten years. In Glarus, Zwingli became involved in politics. Glarus soldiers were often used as mercenaries in Europe. Switzerland was fighting with its neighbors: France, the Habsburgs, and the Papal States. Zwingli supported the Pope. In return, Pope Julius II gave Zwingli money every year. Zwingli served as a chaplain in several wars in Italy. This included the Battle of Novara in 1513.

However, the Swiss suffered a big defeat in the Battle of Marignano. This changed opinions in Glarus. People started to favor France over the Pope. Zwingli, who supported the Pope, was in a difficult spot. He decided to move to Einsiedeln in the canton of Schwyz. By this time, he believed that mercenary service was wrong. He also thought that Swiss unity was very important. Some of his early writings, like The Ox (1510), criticized the mercenary system. He used stories and humor to make his point.

Focus on Study and Move to Zürich

Zwingli stayed in Einsiedeln for two years. During this time, he focused on church activities and his studies. He improved his Greek and started learning Hebrew. His library had over three hundred books. He read works from ancient times, early church writers, and medieval scholars. He exchanged letters with other Swiss humanists. He also began to study the writings of Erasmus. Zwingli met Erasmus in Basel between 1514 and 1516. Erasmus's influence led Zwingli to become more peaceful and focus on preaching.

In late 1518, the main priest position at the Grossmünster in Zürich became open. The church leaders knew Zwingli was a good preacher and writer. His connection with humanists was important. Many church leaders liked Erasmus's ideas for reform. Also, Zürich politicians liked that Zwingli was against France and mercenary service. On December 11, 1518, Zwingli was chosen as the priest. On December 27, he moved to Zürich for good.

Zürich Ministry Begins (1519–1521)

On January 1, 1519, Zwingli gave his first sermon in Zürich. Instead of preaching on the usual Sunday Bible lesson, he did something different. He started reading through the Gospel of Matthew from Erasmus's New Testament. He explained it verse by verse during his sermon. This method is called lectio continua. He continued this way until he finished Matthew. Then he did the same with the Acts of the Apostles, the New Testament letters, and finally the Old Testament. He wanted to encourage moral and church improvements.

Zwingli's religious ideas slowly became clear in his sermons. He spoke out against bad behavior. He even named people he was criticizing. He accused monks of being lazy and living too well. In 1519, Zwingli said that worshiping saints was wrong. He said people needed to know the true stories from the fake ones. He questioned the idea of hellfire. He also said that unbaptized children were not doomed. He even questioned the power of excommunication (being kicked out of the church). His strongest impact was when he said that tithing (giving a tenth of one's income to the church) was not a divine rule. This went against the church's money interests. Zwingli said he was not inventing new ideas. He said his teachings were based only on the Bible.

In August 1519, the plague hit Zürich. At least one in four people died. Many rich people left the city. But Zwingli stayed and continued his duties as a pastor. In September, he got the disease and almost died. He wrote a poem, Zwingli's Pestlied, about preparing for death.

After he recovered, Zwingli's opponents remained a small group. When a position opened among the Grossmünster church leaders, Zwingli was chosen on April 29, 1521. This made him a full citizen of Zürich. He also kept his job as the main priest of the Grossmünster.

Early Conflicts (1522–1524)

The first public argument about Zwingli's preaching happened during Lent in 1522. On March 9, Zwingli and about a dozen others deliberately broke the fasting rule. They cut and ate two smoked sausages. This event, known as the Affair of the Sausages, is seen as the start of the Reformation in Switzerland. Zwingli defended his actions in a sermon. He said that the Bible does not have a general rule about food. So, breaking such a rule is not a sin.

The church leaders in Constance reacted by sending a group to Zürich. The city council criticized the fasting violation. But they also took responsibility for church matters. They asked religious leaders to clarify the issue. The bishop replied on May 24. He warned the Grossmünster and the city council. He repeated the traditional church rules.

After this, Zwingli and his humanist friends asked the bishop to end the rule that priests could not marry. This was not just an idea for Zwingli. He had secretly married a widow named Anna Reinhart earlier that year. Everyone knew they lived together. Their public wedding happened on April 2, 1524, three months before their first child was born. They had four children: Regula, William, Huldrych, and Anna. The bishop told the Zürich government to keep the church rules. Other Swiss priests joined Zwingli's side. This encouraged him to write his first major statement of faith, Apologeticus Archeteles. He defended himself against charges of causing trouble and heresy. He said the church leaders had no right to judge church matters because they were corrupt.

Zürich Debates (1523)

The events of 1522 did not solve the problems. The conflict between Zürich and the bishop continued. Tensions also grew among Zürich's partners in the Swiss Diet (assembly). On December 22, the Diet told its members to ban the new teachings. This was a strong message against Zürich. The city council felt they had to act and find their own solution.

First Public Debate

On January 3, 1523, the Zürich city council invited all the clergy (church leaders) from the city and nearby areas. They wanted to hear everyone's opinions. The bishop was invited to attend or send someone. The council would then decide who could continue to preach their views. This meeting, the first Zürich debate, happened on January 29, 1523.

About six hundred people attended the meeting. The bishop sent a group led by his main representative, Johannes Fabri. Zwingli presented his ideas in 67 points, called the Schlussreden. Fabri was not ready for a scholarly debate. He was also told not to discuss deep theology with ordinary people. He simply insisted on the need for church authority. The council decided that Zwingli could continue preaching. All other preachers had to teach only according to the Bible.

Second Public Debate

In September 1523, Leo Jud, Zwingli's close friend and a pastor, publicly asked for statues of saints and other religious images to be removed. This led to protests and image-breaking. The city council decided to discuss the issue of images in a second debate. The meaning of the Mass and its sacrificial nature was also discussed. Supporters of the Mass said that communion was a real sacrifice. Zwingli said it was a meal to remember Christ. Like the first debate, invitations were sent to Zürich clergy and the bishop of Constance. This time, ordinary people from Zürich, other church areas, the University of Basel, and the twelve Swiss cantons were also invited. About nine hundred people attended. But neither the bishop nor the Swiss cantons sent representatives. The debate started on October 26, 1523, and lasted two days.

Zwingli again led the debate. His opponent was Konrad Hofmann, who had supported Zwingli's election at first. A group of young men also took part. They wanted faster reforms. They argued for adult baptism instead of infant baptism. This group was led by Conrad Grebel, who started the Anabaptist movement. During the first three days, they discussed images and the Mass. But the arguments turned to who had the power to decide these issues: the city council or the church.

Konrad Schmid, a priest and Zwingli's follower, made a practical suggestion. Since not everyone thought images were worthless, he suggested that pastors preach about it. He believed people's opinions would slowly change. Then, images would be removed voluntarily. Schmid disagreed with the radical group and their image-breaking. But he supported Zwingli's position. In November, the council passed rules supporting Schmid's idea. Zwingli wrote a booklet about the duties of a minister, Kurze, christliche Einleitung. The council sent it to the clergy and the Swiss cantons.

Reformation in Zürich (1524–1525)

In December 1523, the council set a deadline of Pentecost in 1524. By then, they wanted a solution for removing the Mass and images. Zwingli gave his formal opinion in Vorschlag wegen der Bilder und der Messe. He did not ask for an immediate, total removal. The council decided to remove images in Zürich in an orderly way. But rural churches could remove them if most people voted for it. The decision on the Mass was put off.

Changes from the Reformation were seen in early 1524. Candlemas was not celebrated. Priests stopped wearing special robes in processions. People did not carry palms on Palm Sunday. Church altars remained covered after Lent. Konrad Hofmann and his followers opposed these changes. But the council decided to keep the government's rules. When Hofmann left the city, opposition from other pastors against the Reformation ended. The bishop of Constance tried to stop the changes. Zwingli wrote an official response for the council. This led to Zürich cutting all ties with the bishop's church area.

The council had hesitated to end the Mass. But fewer people were practicing traditional church rituals. This allowed pastors to stop celebrating Mass unofficially. Since individual pastors were changing their practices, Zwingli created a new communion service in German. This was published in Aktion oder Brauch des Nachtmahls. Before Easter, Zwingli and his closest friends asked the council to end the Mass. They wanted to introduce the new public worship order.

On Maundy Thursday, April 13, 1525, Zwingli celebrated communion using his new service. Simple wooden cups and plates were used. The people sat at tables to show it was a meal. The sermon was the most important part of the service. There was no organ music or singing. Zwingli suggested celebrating communion only four times a year. This showed how important the sermon was.

For some time, Zwingli had accused begging monks of being hypocrites. He demanded that their orders be ended. He wanted their wealth used to help the truly poor. He suggested turning monasteries into hospitals and welfare centers. This was done by reorganizing the Grossmünster and Fraumünster foundations. Remaining nuns and monks were given pensions. The council took over church properties. They set up new welfare programs for the poor.

Zwingli asked for permission to start a Latin school, the Prophezei or Carolinum, at the Grossmünster. The council agreed. It officially opened on June 19, 1525, with Zwingli and Jud as teachers. Its purpose was to retrain and re-educate the clergy. The Zürich Bible translation is traditionally linked to Zwingli. It was printed by Christoph Froschauer. This Bible translation shows the teamwork from the Prophecy school.

Conflict with the Anabaptists (1525–1527)

Soon after the second Zürich debate, many in the radical wing of the Reformation felt Zwingli was giving in too much to the Zürich council. They did not believe in the role of civil government in church matters. They wanted to immediately create a community of true believers. Conrad Grebel, a leader of the radicals and the Anabaptist movement, spoke badly of Zwingli in private. On August 15, 1524, the council insisted that all newborn babies must be baptized. Zwingli secretly talked with Grebel's group. In late 1524, the council called for official discussions. When talks failed, Zwingli published Wer Ursache gebe zu Aufruhr. This book explained the opposing views. On January 17, 1525, a public debate was held. The council sided with Zwingli. Anyone who refused to have their children baptized had to leave Zürich. The radicals ignored these rules. On January 21, they met at the home of another radical leader, Felix Manz. Grebel and a third leader, George Blaurock, performed the first recorded adult baptisms for Anabaptists.

On February 2, the council repeated the rule about baptizing all babies. Some who did not obey were arrested and fined, including Manz and Blaurock. Zwingli and Jud interviewed them. More debates were held before the Zürich council. Meanwhile, the new teachings spread to other parts of Switzerland and some German towns. From November 6–8, the last debate on baptism took place in the Grossmünster. Grebel, Manz, and Blaurock defended their cause against Zwingli, Jud, and other reformers. There was no real discussion. Each side stuck to its views. The debates turned into shouting matches.

The Zürich council decided that no compromise was possible. On March 7, 1526, they issued a strict rule: no one should re-baptize another person, or they would face death. Zwingli technically had nothing to do with this rule, but there is no sign he disagreed. Felix Manz had promised to leave Zürich and stop baptizing. But he deliberately returned and continued the practice. He was arrested, tried, and executed on January 5, 1527. He was the first Anabaptist to die for his beliefs. Three more followed. After that, all other Anabaptists either fled or were expelled from Zürich.

Reformation Across Switzerland (1526–1528)

On April 8, 1524, five cantons formed an alliance. These were Lucerne, Uri, Schwyz, Unterwalden, and Zug. They called themselves die fünf Orte (the Five States). Their goal was to protect themselves from Zwingli's Reformation. They contacted opponents of Martin Luther, like Johann Eck. Eck had debated Luther in 1519. Eck offered to debate Zwingli, and Zwingli accepted. However, they could not agree on who would judge the debate, where it would be held, or if the Swiss Diet would act as a court. Because of these disagreements, Zwingli decided not to attend the debate. On May 19, 1526, all the cantons sent delegates to Baden. Zürich's representatives were there, but they did not take part. Eck led the Catholic side. The reformers were represented by Johannes Oecolampadius from Basel. He was a theologian who had friendly letters with Zwingli. While the debate happened, Zwingli was kept informed. He printed pamphlets with his opinions. But it did not help much. The Diet decided against Zwingli. He was to be banned, and his writings were not to be shared. Of the thirteen Swiss cantons, Glarus, Solothurn, Fribourg, Appenzell, and the Five States voted against Zwingli. Bern, Basel, Schaffhausen, and Zürich supported him.

The Baden debate showed a deep split in Switzerland over religion. The Reformation was now spreading to other states. The city of St Gallen, which was allied with Switzerland, had a reformed mayor, Joachim Vadian. The city ended the Mass in 1527, just two years after Zürich. In Basel, Zwingli was close to Oecolampadius. But the government did not officially approve any reforms until April 1, 1529, when the Mass was forbidden. Schaffhausen, which had followed Zürich closely, officially adopted the Reformation in September 1529.

In Bern, Berchtold Haller, a priest, and Niklaus Manuel, a poet and politician, had supported the reformed cause. But it was only after another debate that Bern became a canton of the Reformation. Three hundred and fifty people took part. This included pastors from Bern and other cantons. Theologians from outside Switzerland also came, like Martin Bucer from Strasbourg. Eck and Fabri refused to attend. The Catholic cantons did not send representatives. The meeting started on January 6, 1528, and lasted almost three weeks. Zwingli was the main defender of the Reformation. He preached twice in the main church. On February 7, 1528, the council decided to establish the Reformation in Bern.

First Kappel War (1529)

Even before the Bern debate, Zwingli was trying to create an alliance of reformed cities. Once Bern officially accepted the Reformation, a new alliance was formed. It was called das Christliche Burgrecht (the Christian Civic Union). The first meetings were held in Bern in January 1528. Representatives from Bern, Constance, and Zürich attended. Other cities like Basel, Biel, Mülhausen, Schaffhausen, and St Gallen eventually joined. The Five (Catholic) States felt surrounded. So, they looked for allies outside Switzerland. After two months of talks, the Five States formed die Christliche Vereinigung (the Christian Alliance) with Ferdinand of Austria on April 22, 1529.

Soon after the Austrian treaty, a reformed preacher named Jacob Kaiser was captured and executed in Schwyz. This made Zwingli very angry. He wrote Ratschlag über den Krieg (Advice About the War) for the government. He explained why they should attack the Catholic states. Before Zürich could act, a group from Bern arrived. They asked Zürich to settle the matter peacefully. Manuel from Bern said that an attack would put Bern in danger. He added, "You cannot really bring faith by means of spears and halberds." However, Zürich decided to act alone. They knew Bern would have to follow. War was declared on June 8, 1529. Zürich gathered an army of 30,000 men. The Five States were left by Austria and could only gather 9,000 men. The two armies met near Kappel. But war was avoided because of Hans Aebli, a relative of Zwingli. He asked for a ceasefire.

Zwingli had to state the terms of the ceasefire. He demanded that the Christian Alliance be broken up. He also wanted reformers to preach freely in Catholic states. He asked for the mercenary pension system to be banned. He also wanted war payments and money for Jacob Kaiser's children. Manuel was involved in the talks. Bern was not ready to insist on free preaching or banning the pension system. Zürich and Bern could not agree. The Five (Catholic) States only promised to end their alliance with Austria. This was a big disappointment for Zwingli. It marked the start of his losing political influence. The first peace treaty of Kappel ended the war on June 24.

Marburg Colloquy (1529)

While Zwingli worked on Swiss politics, he also developed his religious ideas. The famous disagreement between Luther and Zwingli was about the meaning of the eucharist (communion). This started when Andreas Karlstadt, Luther's former colleague, published three pamphlets. Karlstadt said that Christ was not truly present in the communion bread and wine. These pamphlets, published in 1524, were approved by Oecolampadius and Zwingli. Luther rejected Karlstadt's ideas. He saw Zwingli as supporting Karlstadt. Zwingli began to write his thoughts on the eucharist. He wrote de Eucharistia (On the Eucharist). Zwingli believed that Christ had gone to heaven and was at God's right hand. So, he said Christ's human body could not be in two places at once. Unlike his divine nature, Christ's human body was not everywhere. So, it could not be in heaven and also in the communion elements.

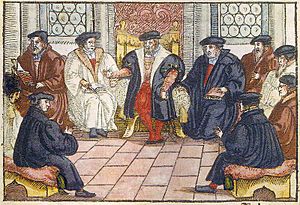

By spring 1527, Luther strongly reacted to Zwingli's views. The argument continued until 1528. Then, people tried to bring Lutherans and Zwinglians together. Philip of Hesse wanted to form a political alliance of all Protestant groups. He invited both sides to Marburg to discuss their differences. This meeting became known as the Marburg Colloquy.

Zwingli accepted Philip's invitation. He truly believed he could convince Luther. Luther, however, did not expect anything good from the meeting. Philip had to urge him to attend. Zwingli, with Oecolampadius, arrived on September 28, 1529. Luther and Philipp Melanchthon arrived soon after. Other theologians also took part.

The debates were held from October 1–4. The results were published in fifteen Marburg Articles. The participants agreed on fourteen of the articles. But the fifteenth article showed their different views on Christ's presence in the eucharist. They could not agree on this point. They left without reaching an agreement. Both Luther and Zwingli agreed that the bread in communion was a sign. But for Luther, what the bread meant (Christ's body) was present in, with, and under the bread itself. For Zwingli, the sign and what it meant were separated by a distance, like the distance between heaven and earth.

The failure to agree caused strong feelings on both sides. Zwingli cried as they left. He said, "There are no people on earth with whom I would rather be at one than the [Lutheran] Wittenbergers." Because of these differences, Luther at first refused to see Zwingli and his followers as Christians.

Politics, Beliefs, and Death (1529–1531)

After the Marburg Colloquy failed and Switzerland split, Zwingli aimed for an alliance with Philip of Hesse. He wrote many letters to Philip. Bern refused to join. But after a long process, Zürich, Basel, and Strasbourg signed a defense treaty with Philip in November 1530. Zwingli also talked with France's representative. But they were too far apart. France wanted to stay friends with the Five States. Attempts to ally with Venice and Milan also failed.

While Zwingli worked on these alliances, Charles V, the Holy Roman Emperor, invited Protestants to the Augsburg Diet. He wanted them to present their beliefs so he could make a decision. The Lutherans presented the Augsburg Confession. Under Martin Bucer's leadership, the cities of Strasbourg, Constance, Memmingen, and Lindau created the Tetrapolitan Confession. This document tried to find a middle ground between Lutherans and Zwinglians.

It was too late for Zwingli's allied cities to create their own statement of faith. Zwingli then wrote his own personal statement, Fidei ratio (Account of Faith). In it, he explained his faith in twelve points, matching the Apostles' Creed. The tone was strongly against both Catholics and Lutherans. The Lutherans did not officially react, but they criticized it privately. Zwingli and Luther's old opponent, Johann Eck, attacked Zwingli's statement in a publication.

When Philip of Hesse formed the Schmalkaldic League in late 1530, the four cities of the Tetrapolitan Confession joined. They joined based on a Lutheran understanding of that confession. Zürich, Basel, and Bern also thought about joining. But Zwingli could not agree with the Tetrapolitan Confession. He wrote a harsh refusal to Bucer. This offended Philip so much that relations with the League ended. Zwingli's allied cities now had no outside friends to help with religious conflicts in Switzerland.

The peace treaty from the First Kappel War did not clearly state if preaching should be allowed in Catholic states. Zwingli thought it meant preaching should be permitted. But the Five States stopped any attempts at reform. Zwingli's allied cities considered different ways to pressure the Five States. Basel and Schaffhausen preferred peaceful talks. Zürich wanted armed conflict. Zwingli strongly supported attacking the Five States. Bern took a middle position, which eventually won out. In May 1531, Zürich reluctantly agreed to block food supplies. This blockade did not work. In October, Bern decided to stop the blockade. Zürich wanted to continue it. Zwingli's allied cities started to argue among themselves.

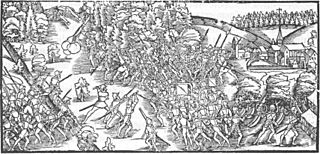

On October 9, 1531, the Five States surprisingly declared war on Zürich. Zürich's army was slow to get ready because of internal arguments. On October 11, 3500 poorly prepared men met a Five States army almost twice their size near Kappel. Many pastors, including Zwingli, were among the soldiers. The battle lasted less than an hour. Zwingli was among the 500 people who died in the Zürich army.

Zwingli saw himself first as a soldier of Christ. Second, he was a defender of his country, Switzerland. Third, he was a leader of Zürich, where he had lived for twelve years. He died at age 47, not for Christ or Switzerland, but for Zürich.

Zwingli's Beliefs

The Bible as the Foundation

For Zwingli, the most important part of his beliefs was the Bible. He always referred to the Bible in his writings. He believed its authority was higher than church councils or early church leaders. However, he still used other sources to support his arguments. Zwingli's way of understanding the Bible came from his education in humanism and his Reformed view of the Bible. He did not take every passage literally, especially when arguing with the Anabaptists. He used methods like synecdoche (using a part to represent a whole) and comparisons. Two comparisons he used well were between baptism and circumcision, and between communion and Passover. He also looked at the immediate context of a passage. He tried to understand its purpose and compared different Bible passages.

Understanding Sacraments

Zwingli did not like how the word sacrament was used in his time. For many people, it meant a holy action that had power to remove sin. For Zwingli, a sacrament was a starting ceremony or a promise. He said the word came from sacramentum, meaning an oath. In his early writings on baptism, he said baptism was an example of such a promise. He accused Catholics of superstition when they believed baptismal water had power to wash away sin. Later, when arguing with the Anabaptists, he defended infant baptism. He said there was no rule against it. He argued that baptism was a sign of a promise with God. It replaced circumcision from the Old Testament.

The Eucharist (Communion)

Zwingli viewed the eucharist (communion) in a similar way to baptism. During the first Zürich debate in 1523, he said that no actual sacrifice happened during the Mass. He argued that Christ made the sacrifice only once, forever. So, the eucharist was "a memorial of the sacrifice." He developed his view further. He concluded that the words of institution ("This is my body") meant "signifies." He used various Bible passages to argue against transubstantiation (the belief that the bread and wine literally become Christ's body and blood). He also argued against Luther's views. A key Bible verse for him was John 6:63, "It is the Spirit who gives life, the flesh is of no avail." Zwingli's approach to understanding the eucharist was a main reason he could not agree with Luther.

Zwingli and Luther's Ideas

The influence of Luther on Zwingli's religious development has been a long-standing topic of discussion. Some scholars try to show Luther as the first reformer. Zwingli himself strongly said he was independent of Luther. Recent studies support this claim. Zwingli seems to have read Luther's books to find support for his own ideas. He agreed with Luther's stand against the Pope. Like Luther, Zwingli also admired Augustine, an early Christian theologian.

Music in Zwingli's Life

Zwingli loved music and could play several instruments. These included the violin, harp, flute, dulcimer, and hunting horn. He sometimes played his lute for the children in his church. He was so well known for his playing that his enemies made fun of him. They called him "the evangelical lute-player and fifer." Three of Zwingli's hymns have survived. These are the Pestlied (Plague Song), an adaptation of Psalm 65, and the Kappeler Lied. The Kappeler Lied is thought to have been written during the first Kappel War. These songs were not meant for church services.

Zwingli criticized priests chanting and monastic choirs. His criticism started in 1523 when he attacked certain worship practices. He linked music with images and special robes. He felt these things distracted people from true spiritual worship. It is not known what he thought of music in early Lutheran churches. Zwingli removed instrumental music from worship in his church. He said God had not commanded it in worship. The organist of the People's Church in Zürich reportedly cried when the large organ was broken up. Although Zwingli did not say much about congregational singing, he did not encourage it. However, scholars have found that Zwingli did support a role for music in the church. One scholar, Gottfried W. Locher, wrote that Zwingli was not against church singing. He said Zwingli's criticism was only about medieval Latin chanting by priests and choirs. Locher also said that Zwingli "freely allowed vernacular psalm or choral singing." He even seemed to want "lively, antiphonal, unison recitative." Locher summarized Zwingli's view on church music: "The chief thought in his conception of worship was always 'conscious attendance and understanding'—'devotion', yet with the lively participation of all concerned."

Zwingli's Lasting Impact

Zwingli was a humanist and a scholar. He had many loyal friends and students. He could talk easily with ordinary people and with rulers like Philip of Hesse. He is sometimes seen as a strict reformer. But he also had a great sense of humor. He used funny stories and jokes in his writings. He cared more about social duties than Luther did. He truly believed that people would accept a government guided by God's word. He worked hard to help the poor. He believed a truly Christian community should care for them.

In December 1531, the Zürich council chose Heinrich Bullinger (1504–1575) to take Zwingli's place. Bullinger quickly made it clear that Zwingli's beliefs were correct. He defended Zwingli as a prophet and a martyr. During Bullinger's time, the religious divisions in Switzerland became stable. Bullinger brought the reformed cities and cantons together. He helped them recover from the defeat at Kappel. Zwingli had started big reforms. Bullinger made them stronger and better.

Scholars find it hard to fully understand Zwingli's impact on history. This is for several reasons. There is no clear definition of "Zwinglianism". Also, Zwinglianism changed under Bullinger. And research into Zwingli's influence on Bullinger and John Calvin is still new. Bullinger adopted most of Zwingli's beliefs. Like Zwingli, he summarized his beliefs many times. The most famous is the Second Helvetic Confession of 1566. Meanwhile, Calvin led the Reformation in Geneva. Calvin disagreed with Zwingli on the eucharist. He criticized Zwingli for seeing it as only a symbolic event. However, in 1549, Bullinger and Calvin managed to overcome their differences. They created the Consensus Tigurinus (Zürich Consensus). They said the eucharist was not just symbolic. But they also rejected Luther's view that Christ's body and blood were literally in the elements. With this agreement, Calvin became important in the Swiss Reformed Churches and later worldwide.

The Swiss Reformed churches see Zwingli as their founder. The Reformed Church in the United States also does. Scholars wonder why Zwinglianism has not spread more widely. This is even though Zwingli's beliefs are considered the first form of Reformed theology. Although his name is not widely known, Zwingli's legacy lives on in the basic beliefs of today's Reformed churches. He is often called, after Martin Luther and John Calvin, the "Third Man of the Reformation."

In 2019, Swiss director Stefan Haupt released a Swiss-German film about Zwingli's life: Zwingli. It was filmed in Swiss German with French and English subtitles.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Ulrico Zuinglio para niños

In Spanish: Ulrico Zuinglio para niños