Project Hula facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Project Hula |

|

|---|---|

| Part of the Pacific War of World War II | |

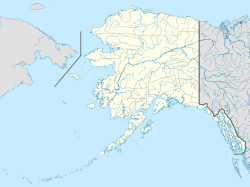

Fort Randall at Cold Bay, Territory of Alaska, in 1942. Project Hula took place here in 1945. The head of the bay itself is at center right.

|

|

| Operational scope | Transfer of US Navy vessels to the Soviet Union in anticipation of the Invasion of Japan |

| Location | Cold Bay, Territory of Alaska |

| Date | 20 March 1945 – 30 September 1945 |

| Outcome | Japan surrendered before completion of the operation |

Project Hula was a secret program during World War II where the United States gave naval ships to the Soviet Union. This happened because the Soviets were expected to join the war against Japan. The project was based at Cold Bay in Alaska and ran during the spring and summer of 1945. It was the biggest and most ambitious program of its kind during the entire war.

Contents

Why Project Hula Started

For a long time, the Russian Empire (and later the Soviet Union) and Japan had a difficult relationship. They even fought a war in 1904–1905. Later, in the 1930s, Japan's actions in East Asia led to small fights with Soviet forces. However, in 1941, the two countries signed a Soviet–Japanese Neutrality Pact, promising not to attack each other.

When World War II started, the Soviet Union joined the Allies after Germany invaded in 1941. Japan also joined the war by attacking Allied forces in the Pacific. Even though they were on opposite sides, neither country wanted to fight the other. Both were busy with their own wars. The Soviet leader, Josef Stalin, said the Soviets could only join the war against Japan after Germany was defeated.

In October 1944, Stalin finally offered to join the war against Japan. He said it would happen three months after Germany surrendered. But he also asked the Allies for a lot of help. The Soviet Union had lost many soldiers and a lot of money fighting Germany. So, they needed help building up their military in East Asia before fighting Japan. The United States agreed to help, and this aid program was called MILEPOST.

As part of MILEPOST, American and Soviet naval leaders met in December 1944. They agreed that the United States would give the Soviets many ships and aircraft. These included escort ships, landing craft, and minesweepers. They also decided that American experts would teach Soviet crews how to use these ships.

Choosing the Secret Base

|

Cold Bay

|

|

|---|---|

In January 1945, the head of the Soviet Navy, Admiral Nikolai Gerasimovich Kuznetsov, suggested that the training and ship transfers happen in the Aleutian Islands of Alaska. He wanted a place with very few civilians to keep the program a secret from Japan. He thought Dutch Harbor would be a good choice because Soviet ships often visited there.

However, on January 18, 1945, the U.S. Navy's top officer, Fleet Admiral Ernest J. King, asked Admiral Frank Jack Fletcher about Dutch Harbor. Fletcher said no. Dutch Harbor didn't have enough housing or training space. Its harbor was also too small and exposed to rough seas. He suggested Cold Bay instead. Cold Bay had a protected harbor, good facilities, and no civilians, which made it perfect for a secret program. King agreed to Cold Bay.

Later, at the Yalta Conference in February 1945, Kuznetsov still preferred Dutch Harbor. But when King told him about Cold Bay and showed him on a map, Kuznetsov quickly agreed.

Getting Ready for Training

Project Hula officially began in mid-February 1945. The U.S. Navy ordered the old United States Army base at Cold Bay, Fort Randall, to be reopened and fixed up. The first Soviet trainees were expected to arrive by April 1, 1945.

A big challenge was how to get the Soviet sailors to Cold Bay. They eventually decided that Soviet merchant ships, which were already sailing from the U.S. West Coast to the Soviet Far East with supplies, would carry about 600 men at a time.

The final plan was to transfer 180 ships to the Soviet Union by November 1, 1945. This included patrol frigates, minesweepers, landing craft, submarine chasers, and floating workshops. About 15,000 Soviet Navy personnel would be trained to operate them. After being given to the Soviets, the ships would sail in convoys from Cold Bay, escorted by the U.S. Navy.

The first Soviet personnel, including a rear admiral and his staff, were expected in late March or early April 1945. They were told to follow American orders without question while at Cold Bay.

The U.S. Navy created Naval Detachment No. 3294 specifically for Project Hula. Commander William S. Maxwell was put in charge. He arrived at Cold Bay on March 19, 1945, and was promoted to captain. He found that the base needed a lot of work. He set up housing, classrooms, movie theaters, and even a softball field. He also found instructors for courses like radio, radar, engineering, and gunnery.

The first Soviet trainees arrived between April 10 and 14, 1945. Nearly 2,400 Soviet personnel arrived, joining 1,350 American staff. Rear Admiral Boris Dimitrievich Popov arrived on April 11 and took command of the Soviet personnel.

Training and Ship Transfers

Training began on April 16, 1945. The Soviet sailors were very serious about their training. A big challenge was that they didn't know much about radar or sonar. Also, there weren't enough training manuals in Russian. So, American and Soviet staff worked together to create Russian-language manuals.

Another problem was that the ships often arrived without all the necessary equipment. Or they had equipment that wasn't supposed to be transferred. Needed equipment had to be flown in daily. Also, some of the wooden ships were damaged in the rough seas. Repairs were far away, causing delays.

Despite these issues, the first group of transferred ships left Cold Bay for the Soviet Union on May 28, 1945. This group included minesweepers and auxiliary motor minesweepers.

Training for the large infantry landing craft (LCI(L)) was very successful. The first group of these ships left Cold Bay on June 11, 1945. All Soviet LCI(L) crews left for the Soviet Union by the end of July 1945.

The 30 Tacoma-class patrol frigates were the biggest and most expensive ships to be transferred. The first Soviet sailors for these ships arrived in June 1945 and began training. The first 10 frigates were transferred on July 12, 1945, and left Cold Bay on July 15.

Throughout the project, relations between Soviet and American personnel were friendly. The best Soviet trainees even stayed to help train others. By July 31, 1945, 100 of the 180 planned ships had been transferred.

The War Ends, Project Hula Stops

As promised, the Soviet Union declared war on Japan on August 8, 1945. They immediately launched an attack against Japanese forces in Northeast Asia. Even though Japan surrendered to the Allies on September 2, 1945, Soviet attacks continued until September 5. By then, Soviet forces had taken over Manchuria, northern Korea, southern Sakhalin Island, and the Kuril Islands. Project Hula remained a secret, even with the Soviets now openly fighting Japan.

The Soviet entry into the war made cooperation at Cold Bay even better. American and Soviet leaders worked to speed up training and transfers. On September 2, 1945, the day Japan surrendered, the Soviet Navy took control of two more patrol frigates. On September 4, the last four ships of Project Hula were given to the Soviets.

On September 5, 1945, orders came to stop transferring ships, except for those already being trained. This canceled the transfer of many ships. The last four patrol frigates transferred stayed at Cold Bay for more training. They left for the Soviet Union on September 17, 1945. The remaining Soviet personnel left Cold Bay on September 27, 1945. The base at Cold Bay was officially closed on September 30, 1945.

What Happened to the Ships?

Project Hula was the largest ship transfer program of World War II. In 142 days, about 12,000 Soviet Navy personnel were trained, and 149 ships were transferred at Cold Bay.

In Soviet service, the ships were given new names and designations. For example, patrol frigates became "EK" (escort vessel), and minesweepers became "T" (minesweeper).

Some of the ships transferred in Project Hula were used in combat. Five of the landing craft were lost in battle on August 18, 1945, during the Soviet landings on Shumshu in the Kuril Islands. They were sunk by Japanese coastal artillery.

After World War II, U.S. law said that all ships given under Lend-Lease had to be returned. But relations between the Soviet Union and the United States became difficult as the Cold War began. In 1946, the U.S. asked for the ships back.

By 1949, the Soviet Union agreed to return the patrol frigates. They returned 27 of them. One frigate, the former USS Belfast, was damaged in a storm and couldn't be returned. Negotiations for the landing craft took longer, but 15 of them were returned in 1955. By 1957, only 18 of the Project Hula ships still with the Soviets were still working.

The U.S. Navy didn't actually want many of the older ships back because they were expensive to take care of. So, some ships were just officially returned and then sold for scrap or destroyed by the Soviets. Two auxiliary motor minesweepers were given to China. The rest of the ships still with the Soviets were either scrapped or destroyed.

Could the Soviets Invade Japan?

Some people thought Project Hula would give the Soviet Union the power to invade the main Japanese islands. However, many historians believe it wasn't enough. By December 1945, the Soviets had received 3,741 American Lend-Lease ships, but only 36 of them were big enough for an invasion of Japan. This wasn't enough to pose a major threat to Japanese forces on the mainland.

For example, in their invasion of southern Sakhalin on August 11, the Soviets outnumbered the Japanese but struggled to advance due to strong resistance. The Soviet invasion of the Kuril Islands happened after Japan had already surrendered on August 15. Even then, Japanese forces fought fiercely. In the Battle of Shumshu, the Soviets had more troops but no tanks or large warships. The Japanese had a strong garrison with tanks. The battle lasted five days, and the Soviets lost more soldiers than the Japanese. This was the only battle in the 1945 Soviet–Japanese War where Soviet losses were higher. If the war had continued, Soviet losses would have been much higher, and supplying their forces overseas would have been very difficult.

At the time of Japan's surrender, about 50,000 Japanese soldiers were in Hokkaido. The Sea of Japan was heavily patrolled by the Imperial Japanese Navy. If the Soviet Navy had tried to invade, the Japanese would have known.

The Yalta Conference gave the Soviet Union the right to invade southern Sakhalin and the Kuril Islands, but not the main Japanese islands. Some Soviet leaders suggested invading Hokkaido, but most Soviet diplomats and officers disagreed. They said they didn't have enough landing craft and equipment. Trying to invade would put their troops in great danger against strong Japanese defenses. It would also break the agreement with the Western Allies.

In 1947, American leaders wrote a memo about their troops leaving Japan. They believed that Japan would not threaten the U.S. in the future. They also noted that Russia didn't have enough naval forces to invade the Japanese islands. They thought that even if Russia tried, American air and land forces in Japan could stop them.

| Misty Copeland |

| Raven Wilkinson |

| Debra Austin |

| Aesha Ash |