Echo parakeet facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Echo parakeet |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Female by a feeding hopper | |

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Genus: |

Psittacula

|

| Species: |

eques

|

| Subspecies | |

|

|

|

|

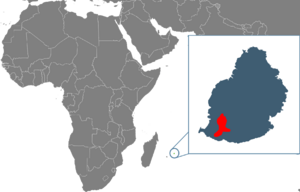

| Current range (red) in Mauritius | |

| Synonyms | |

|

List

Psittacus eques Boddaert, 1783

Psittica torquata Latham, 1822 Palaeornis echo Newton & Newton, 1876 Psittacula krameri echo Peters, 1937 |

|

The echo parakeet (Psittacula eques) is a type of parrot that lives only on the Mascarene Islands. These islands are Mauritius and, in the past, Réunion. It is the only native parrot still alive in the Mascarene Islands. All the others disappeared because of human activities.

Scientists recognize two main types, or subspecies, of this parrot. One is the extinct Réunion parakeet. The other is the living echo parakeet, also called the Mauritius parakeet. For a long time, people weren't sure how these two groups were related. But a DNA study in 2015 showed they are subspecies of the same bird. The Réunion parakeet was named first, so its scientific name, P. eques eques, is used for the whole species. The Mauritius parakeet is called P. eques echo. Their closest relative was another extinct bird, Newton's parakeet from Rodrigues. These three birds are related to the rose-ringed parakeet found in Asia and Africa.

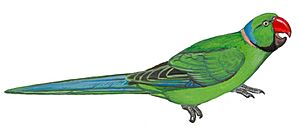

The echo parakeet is about 34 to 42 centimeters (13 to 17 inches) long. It weighs between 167 and 193 grams (5.9 to 6.8 ounces). Its wingspan is 49 to 54 centimeters (19 to 21 inches). This parrot is mostly green. Females are generally darker than males. Both have two collars on their necks. The male has a black and a pink collar. The female has a green collar and a faint black one. The male's upper bill is red, while the female's is black. The skin around their eyes is orange, and their feet are grey. Young birds have a red-orange bill that turns black after they leave the nest. The Réunion parakeet had a full pink collar around its neck. The Mauritius parakeet's collar has a gap at the back. The introduced rose-ringed parakeet on Mauritius looks similar but is smaller and has slightly different colors. Echo parakeets make many different sounds. The most common one sounds like "chaa-chaa, chaa-chaa".

This parrot lives only in native forests, mostly in the Black River Gorges National Park in southwest Mauritius. It lives in trees, staying in the treetops to eat and rest. It builds nests in natural holes in old trees. Usually, two to four white eggs are laid. The female sits on the eggs, and the male brings her food. The female also cares for the young birds. Some pairs are not strictly monogamous, meaning a female might breed with more than one male. The echo parakeet mostly eats fruits and leaves from native plants. But it has also been seen eating introduced plants. The Réunion parakeet likely died out because of hunting and deforestation. It was last seen in 1732. The echo parakeet was also hunted in the past. Its numbers dropped a lot in the 20th century due to habitat loss. In the 1980s, there were only 8 to 12 birds left. It was called "the world's rarest parrot" then. But a big effort to breed them in captivity started in the 1990s. This saved the bird from disappearing. In 2007, its status improved from "critically endangered" to "endangered". By 2019, there were 750 birds, and it was listed as "vulnerable".

Contents

How Scientists Study Them

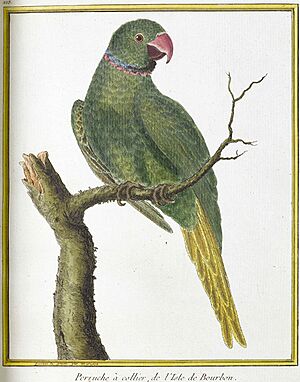

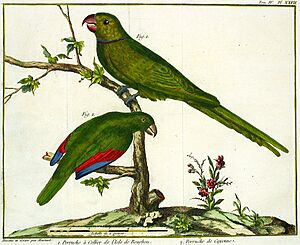

Early travelers to Réunion and Mauritius mentioned green parakeets. In 1674, a French traveler, Sieur Dubois, first wrote about them on Réunion. In 1732, Jean-François Charpentier de Cossigny saw them on Mauritius. French naturalists called the Réunion parakeets "double-collared parakeets." They described them from birds brought to France.

In 1783, a Dutch naturalist named Pieter Boddaert gave the Réunion parakeet its scientific name, Psittacus eques. This name came from a drawing by French artist François-Nicolas Martinet. The drawing showed the Réunion bird. The name eques means "horseman" in Latin. It refers to the colors of a French cavalryman. Martinet's drawing is the official "type illustration" for the species.

For a long time, the parakeets of Mauritius and Réunion were often mixed up in old writings. In 1876, British brothers Alfred and Edward Newton suggested that the birds on the two islands might be different. They gave the Mauritius parakeet a new name, Palaeornis echo. This name refers to Echo, a nymph from Greek mythology. They kept the name Palaeornis eques for the Réunion species.

Later, in 1937, an American ornithologist, James L. Peters, classified the Mauritius parakeet as a subspecies of the rose-ringed parakeet. He called it Psittacula krameri echo. He changed the genus name to Psittacula, which is used for other parakeets in Asia and Africa.

In 1987, a British ecologist, Anthony S. Cheke, said that the parakeets of Mauritius and Réunion seemed to be the same species. A conservation biologist, Carl G. Jones, also mentioned an old parakeet skin in a museum in Scotland. This skin might have been from Réunion. Jones thought the skin looked similar to living echo parakeets. He agreed that the parakeets from both islands were the same species (P. eques). But he thought they should be kept as separate subspecies (P. eques eques and P. eques echo) because there wasn't enough information about the extinct bird.

Since the 1970s, the living parakeet of Mauritius has been called the "echo parakeet." It's also known as the Mauritius parakeet. In Mauritius, people call it cateau vert, kato, or katover. The Réunion population is called the Réunion parakeet.

How They Evolved

In 2004, scientists looked at the DNA of Psittacula parakeets. They found that the echo parakeet came from an Indian type of rose-ringed parakeet. It separated from them between 0.7 and 2.0 million years ago. This time matches a period when volcanoes on Mauritius were not active. So, the ancestors of the echo parakeet might have flown from India across the Indian Ocean when the island was forming.

In 2015, scientists successfully got DNA from the old museum skin thought to be from Réunion. They compared it to DNA from Mauritius parakeets. They found that Newton's parakeet from Rodrigues was an ancestor to both the Mauritius and Réunion parakeets. It separated from them 3.82 million years ago. The Mauritius and Réunion parakeets separated from each other only 0.61 million years ago. This small difference suggests they are distinct subspecies.

Here's a family tree showing how they are related:

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Some scientists in 2019 suggested that the Psittacula group should be split into smaller groups. They put the echo parakeet into a new group called Alexandrinus. This group includes its closest relatives, Newton's parakeet and the rose-ringed parakeet.

In 2016, some scientists said the museum skin might not be from Réunion. They thought it could be from Mauritius. They noted that the pink neck ring on the museum skin went all the way around the neck, like old descriptions of the Réunion parakeet. But modern Mauritius parakeets have a gap in the collar. They wondered if the small genetic differences were due to a "genetic bottleneck" (a big drop in population) in Mauritius.

However, in 2018, many scientists, including those who did the DNA studies, agreed that the Edinburgh specimen was indeed a Réunion parakeet. They confirmed that it had a complete pink collar, unlike the Mauritius birds.

In 2021, some scientists argued that the differences between the Mauritius and Réunion populations were not big enough to be separate subspecies. They thought both belonged to a single species with no subspecies. They also said there was no strong proof where the Edinburgh skin came from.

What They Look Like

The echo parakeet is about 34 to 42 centimeters (13 to 17 inches) long. It weighs 167 to 193 grams (5.9 to 6.8 ounces). This makes it smaller than other extinct parrots from Mauritius. Its wingspan is 49 to 54 centimeters (19 to 21 inches). Females are usually a bit smaller than males.

The parrot is mostly green. Its back is darker, and its underside is yellowish. Males are lighter green, and females are darker overall. They have two ring-like collars on their necks that don't quite meet at the back. The male has a black collar and a pink one. The pink collar looks like a crescent from the side. The female has a faint black collar and a green one. This green collar becomes dark green on her cheeks and yellow-green at the back of her neck. Males also have a thin black line from their cere (the fleshy part above the beak) to their eye.

The adult male's upper bill is bright red, and the lower bill is blackish-brown. The female's upper bill is dark, almost black. Their eyes are yellow, but can also be pink or white. The skin around their eyes is orange, and their feet are grey. Young birds have a red-orange bill, like the adult male. But two to three months after they leave the nest, it turns black, like the adult female's. Young birds look similar to the female.

The extinct Réunion parakeet was likely similar to the Mauritius one. But it was a bit larger. Its pink collar went all the way around its neck, unlike the Mauritius subspecies, which has a gap. The Réunion parakeet also seemed to have darker lower parts.

The echo parakeet looks very much like the rose-ringed parakeet, which was brought to Mauritius. But the echo parakeet's green feathers are darker and richer. Its neck has a bluish tint, and its tail is greener and shorter. Female echo parakeets are darker and more emerald green than female rose-ringed parakeets. Unlike the echo parakeet, the rose-ringed parakeet's beak color doesn't change between males and females. The echo parakeet is also stockier and about 25% larger and heavier than the rose-ringed parakeet. It has shorter, wider, and more rounded wings than other Psittacula parrots. Its tail is also shorter and wider.

What Sounds They Make

Echo parakeets make many different sounds. They are loudest before they go to sleep in the evening. They make sounds all year, but more during the breeding season. Their most common sound is a low, nasal squawk, like "chaa-chaa, chaa-chaa." They say this sound alone or in a quick series. Their flight call is very similar.

When they are excited or alarmed, they make a higher-pitched sound, like "chee-chee-chee-chee." This is usually heard when they fly with quick wing beats. If they are bothered or scared, they might make a short, sharp "ark" sound. When they are sitting, they make more musical chirps and whistles. A deep, quiet "werr-werr" and a "prr-rr-rr" purr have also been heard. Males make a special sound during courtship between September and December. They also "growl" when they are angry, like other parrots. The echo parakeet's voice is very different from the rose-ringed parakeet's. The rose-ringed parakeet has higher, faster, and more "excited" sounds.

Where They Live

The echo parakeet now lives only in the native forests of Mauritius. These forests cover less than 2% of the island. They are mainly found in the Black River Gorges National Park in the southwest. They use an area of about 40 square kilometers (15 square miles). Within the park, there are four groups in the north and two in the south.

In the upland forest, they prefer large, old trees like Canarium paniculatum and Mimusops maxima. Other important feeding areas include lowland and scrub forests. The number of parakeets seen in these areas changes each year. This shows how many birds are in the population. The echo parakeet's home is tied to native forests. As these forests are destroyed, their numbers and spread decrease.

A 2012 study showed that before the captive breeding program, parakeets from the more isolated southern areas were genetically different. But after birds were moved around for conservation, their genes mixed. This genetic difference might have been caused by forests being cleared, which separated the groups.

How They Behave

The echo parakeet lives in trees (it is arboreal). It stays in the treetops of the forest to eat and rest. It usually moves alone or in small groups. It is not as social as the rose-ringed parakeet. When flying, the echo parakeet is good at using air currents over hills and cliffs. It flies slower than the rose-ringed parakeet, with slower wing beats. It can fly well, but only for short distances. It can quickly move through openings in the treetops.

Like other birds in Mauritius, echo parakeets are tame. They are tamer in winter when food is scarce. They become more careful in summer when food is easier to find. Breeding birds in nests are not bothered by cars or people looking at their nests. Echo parakeets mostly lose their old feathers (moult) during summer. This process takes several months. The birds are usually done moulting by the end of June. We don't know how long they live, but they can live for at least eight years.

Echo parakeets mostly look for food in the mid-morning and mid-to-late afternoon. Bad weather does not stop them from doing this. Groups rest and clean their feathers (preen) on large trees in the middle of the day. They are most active and noisy in the afternoon when they fly to and from feeding areas. They get very excited an hour before sunset, when they go to sleep. They fly around in groups, calling often. They usually sleep in sheltered spots on hillsides, in trees with thick leaves. They perch close to tree trunks or in holes. Birds usually leave their sleeping spots quietly in the morning.

Raising Young

Echo parakeets breed similarly to other Psittacula parakeets. Most can breed by the time they are two years old. The colors and patterns on their necks and heads are important during courtship. They show how healthy and strong a bird is. The pink collars are raised during displays of dominance. Their eyes also get bigger and smaller.

The breeding season usually starts in August or September. Nests are chosen early in the season. The birds nest in natural holes, often in large, old native trees. These holes are at least 10 meters (33 feet) above the ground. They are usually in horizontal branches, not vertical trunks. The holes are at least 50 centimeters (20 inches) deep and 20 centimeters (7.9 inches) wide. The entrance holes are 10 to 15 centimeters (3.9 to 5.9 inches) wide. Flooding often happens in these holes, but some have features that help prevent it.

Males and females show care for each other all year. The male is usually in charge. This includes the male feeding the female by bringing up food. They also touch beaks and the male cleans the female's neck feathers.

Eggs are laid between August and October, mostly in late September and early October. Sometimes, birds lay eggs again if the first batch fails. A group of eggs (clutch) usually has two to four eggs. The eggs are round and white, about 32.2 by 26.8 millimeters (1.27 by 1.06 inches) and weigh about 11.4 grams (0.40 ounces). The female sits on the eggs for about 21–25 days. During this time, the male feeds her four or five times a day, outside the nest hole. The female also cares for the young birds. She leaves them alone for most of the day after two weeks.

Usually, two young birds are raised. Chicks grow slowly. Dark feathers appear on their backs and wings after five days. Their eyes start to open after ten days. After fifteen days, their eyes are almost fully open. They have fine greenish-grey down feathers. After twenty days, they are fully covered in greenish down. After thirty days, their wing and tail feathers appear. After forty days, all their feathers are well developed. When young birds are old enough, they can growl and bite at anyone who comes near the nest. After fifty days, the chicks are active. They flap their wings and go near the entrance hole. Chicks leave the nest after 50–60 days, between late October and February. They stay near the nest entrance for some time after leaving. They go with their parents to find food as soon as they can fly. They stay with their parents and are fed for two to three months after leaving the nest.

Sometimes, extra adult male echo parakeets act as "helpers." They feed the nesting female and the young birds. These helpers were thought to be linked to more males than females in the 1980s. In the late 1990s, it was found that echo parakeets might not be monogamous. Instead, they might have polyandry, where one female breeds with several males. This kind of breeding helps save the species because it increases genetic diversity.

What They Eat

The echo parakeet mainly eats native Mauritian plants. They also eat small amounts of introduced plants. They eat fruits (53%), leaves (31%), flowers (12%), buds, young shoots, seeds, twigs, and bark or sap (4%). They feed in trees and rarely, if ever, land on the ground. They return to their favorite trees, some of which have been used for generations.

Some important plants in their diet include Calophyllum tacamahaca, Canarium paniculatum, and Tabernaemontana mauritiana. Some fruits have a very hard outer skin that parrots can't easily break. This might have developed to protect the seeds. Some fruits have a hard inner part surrounded by a soft, fleshy part. The parakeets eat the fleshy part and then spit out the hard part. This helps spread the seeds. In 1987, it was reported that they didn't eat the common introduced Psidium cattleianum (strawberry guava). But in 1998, they started eating this and other non-native plants, like star fruit.

Echo parakeets look for food in different areas depending on the season. They use dwarf forest and scrubland all year. They eat different plants as edible parts become available. However, many plants don't produce fruit regularly, and some species are now rare. So, food is not always available. When fruits are scarce in winter and early spring, the birds eat more leaves and spend more time looking for food. The birds wander to find food, sometimes flying several kilometers. They usually look for food in the morning and late afternoon.

Echo parakeets are quiet when they climb around to eat. They use their beaks to remove fruits and flowers. Sometimes they hang upside down to reach food. They hold the food with a foot while eating. When eating Tabernaemontana mauritiana leaves, they often scoop out the soft inner tissue and leave the tough parts. Many leaves and fruits are only partly eaten before being dropped. The parakeets might chew a bite for several minutes before swallowing it.

Fighting and Competition

Psittacula parakeets often group together to loudly scold animals they see as a threat. Echo parakeets might do this during fights over territory. They might also chase other birds. Echo parakeets have been seen chasing rose-ringed parakeets, Mauritius kestrels, white-tailed tropicbirds, and large bats. They regularly mob Mauritius kestrels, flying around them and making alarm calls. They might also react to introduced crab-eating macaques with loud calls. But sometimes they ignore monkeys feeding nearby. They compete with monkeys for food. Their diet also overlaps with that of the pink pigeon, the Mauritius bulbul, and the Mauritian flying fox.

The echo parakeet only defends its territory during the breeding season. It protects the area around its nest tree. Their territorial behavior is not always strong. Outside the breeding season, birds are loosely connected to their breeding areas. They might be aggressive towards other echo parakeets or other species. Both males and females defend the nest before eggs are laid. But the male takes the lead afterward. They first call out, which might be enough to scare away an intruder. If the intruder gets closer, one or both birds will approach it. They will cautiously jump between tree branches and circle slowly around the trees near the nest. Fights are rare.

The rose-ringed parakeet was brought to Mauritius around 1886 and is now thriving there. Its population is estimated at 10,000 birds. It is closely related to the echo parakeet and looks similar. But no mixed-breed birds have been found. They compete for nest sites and probably some food. The two species are usually peaceful towards each other outside the breeding season. They have been seen chasing each other, but also flying together and feeding in the same trees.

The most serious competition between the echo parakeet and the rose-ringed parakeet is for nest sites. The introduced species often takes over holes used by the native parakeets. Echo parakeets are said to give up their nest territories easily without fighting. In 1974, two out of seven echo parakeet nest holes were taken over by rose-ringed parakeets. For several years, only rose-ringed parakeets nested in one area.

Their Status

Why They Declined

There were once seven types of parrots unique to the Mascarene Islands. All but the echo parakeet have disappeared. The others likely became extinct due to too much hunting and deforestation by humans. Also, invasive species brought by humans (like predators and competitors) played a role. On Mauritius, the echo parakeet lived alongside the broad-billed parrot and the Mascarene grey parakeet. The Réunion parakeet lived with the Mascarene parrot and the Mascarene grey parakeet. Newton's parakeet and the Rodrigues parrot lived on nearby Rodrigues.

Around the world, many parrots have been driven to extinction by humans. Island populations are especially vulnerable because they are often tame. Sailors visiting the Mascarene Islands from the late 16th century saw the animals as food. Many other unique species of Mauritius were lost after humans arrived. This includes the dodo, which has become a symbol of extinction. So, the island's ecosystem is badly damaged. The remaining unique animals are still seriously threatened. Before humans arrived, Mauritius was completely covered in forests. Almost all of these have now been lost.

The last report of the Réunion parakeet was from 1732. Scientists were surprised that it disappeared so quickly after humans arrived. Especially since the Mauritius population managed to survive. It is estimated that the Réunion parakeet went extinct around 1730–50 due to hunting and deforestation.

In 1666–1669, a Dutch soldier reported many parrots on Mauritius. Echo parakeets were caught alive with nets. But sometimes they couldn't be caught because they were too high in trees. Parrots were often caught to be given as gifts or sold in the 17th century. The fact that they stayed in high trees shows they had become wary of humans by then. In 1754 and 1756, D. de La Motte described how common echo parakeets were in Mauritius and how they were used for food:

One eats here [in Mauritius] a good number of long-tailed green parrots called perruches whose flesh is black and very good. A hunter can kill three or four dozen in a day. There is a time of year when these birds eat a seed that makes their flesh bitter and even dangerous.

Reports on the echo parakeet's status varied. It was called "quite common" in the 1830s. But by 1876, the Newtons said "its numbers are gradually falling." In 1907, one scientist said the bird was rare and "on the verge of extinction." Areas where the echo parakeet lived were cleared for tea and forestry from the 1950s to the 1970s. The birds were forced into the remaining native habitat. In 1970, about 50 pairs were thought to be left. By 1975, only about 50 individual birds remained. The population dropped even more in the following years. By 1983, only a group of 11 birds was seen. This was believed to be the entire population. This drop might have been linked to cyclone Claudette in December 1979. There was little nesting success, and the parakeets were not reproducing enough to replace themselves.

Saving Them

In the early 1970s, scientists started paying attention to the endangered birds of Mauritius. The Mauritius kestrel was considered the rarest bird in the world by 1973, with only six birds left. The pink pigeon had about 20 birds in the wild. Both species were later saved from extinction by breeding them in captivity.

In 1974, an American biologist, Stanley Temple, started a program to stop the echo parakeet's decline. But these attempts failed. Unlike other Psittacula parakeets, it was hard to keep them alive in captivity. All the birds died. By the 1980s, most Mauritian naturalists believed the echo parakeet would soon be extinct. It was then considered the rarest and most endangered Mascarene bird. It was called "the world's rarest parrot."

In 1980, Carl Jones said the situation was desperate. He stated that the remaining birds had to be caught for captive breeding to save the echo parakeet. By the 1980s, only 8–12 echo parakeets were known. Jones, who had saved the Mauritius kestrel and pink pigeon, focused on the parakeets. A New Zealand conservationist, Don Merton, was invited to help. They used their experience with other birds to create a plan for the echo parakeet.

They treated nests with bug spray to prevent chicks from being killed by nest flies. They secured nest entrances to stop tropic-birds from taking them over. They put smooth PVC around tree trunks and poison nearby to keep away black rats. They also trimmed branches around nest trees to stop monkeys from attacking by jumping from nearby trees. Feeding hoppers were introduced to provide food when it was scarce. It took years for the birds to learn to use them. Nest holes were also made waterproof.

After breeding success improved in the wild, there were 16–22 birds in 1993/94. A captive pair also produced a chick in 1993. Because of the success in saving native birds, the Black River Gorges and nearby areas became the first national park of Mauritius in 1994.

In 1996, six new echo parakeet breeding groups were found. This almost doubled the number of known breeding groups. The echo parakeet became a top project for the Mauritian Wildlife Foundation. They decided to start a captive breeding program at the Gerald Durrell Endemic Wildlife Sanctuary. They found that from three or four eggs, usually only one chick would survive. So, the team started taking the extra chicks. The parents could then more easily raise the remaining chicks. Many extra chicks were taken to the breeding center and raised successfully. The first three birds bred in captivity were released into the wild in 1997.

These hand-reared birds were too tame and naive. They would land on people's shoulders or near cats and mongooses, which then killed them. Jones decided to release the captive-bred birds earlier, after nine to ten weeks. These younger birds were better at joining wild birds and learning survival skills. Captive-bred birds who learned to use feeding hoppers in captivity taught this to wild birds. The number of birds using food hoppers and nest boxes provided by the team increased. By 1998, there were 59–73 birds, including 14 that had been bred in captivity since 1997.

By 2005, 139 captive birds had been released. Intensive management of the wild population stopped in 2006. Since then, only extra food and nest boxes have been provided. By 2007, about 320 echo parakeets lived in the wild, and their numbers were growing. The species was changed from "critically endangered" to "endangered" on the 2007 IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Its numbers were still low, and its range was small. In 2009–2010, 78% of nesting attempts happened in nesting boxes. A record 134 chicks left the nest during this breeding season. By 2016, the population was almost 700 birds.

Even though the echo parakeet is considered saved from extinction, it still needs human help to stay safe from remaining threats. The Black River Gorges National Park had reached its limit for how many birds it could support. So, echo parakeets were released in the mountains of eastern Mauritius around 2016. It has been suggested that birds could be introduced to the other Mascarene Islands. By 2019, the population reached 750 birds in the wild. The species' conservation status was changed to "vulnerable".

What Still Threatens Them

The biggest threat to the species is the destruction and change of its native home. This leads to a loss of feeding areas. It forces the birds to travel far to find food. When food is scarce, the female might not get enough food from the male. She would then have to leave the nest to find food, sometimes abandoning it completely. Parakeets have trouble finding new nest sites if their nests are destroyed or taken by other animals. Many old trees used for nesting have been destroyed by cyclones. Cyclones also kill birds and remove fruit from trees.

Animals that compete for nest holes include bees, wasps, white-tailed tropic-birds, rose-ringed parakeets, common mynas, and rats. Rats and crab-eating macaques eat parakeet eggs and chicks. Monkeys are also serious competitors for food. They strip fruits off trees before they are ripe. Chicks are also threatened by bloodsucking larvae of tropical nest flies. These flies cause many chick deaths. African giant land-snails can suffocate chicks with their slime when they enter nests looking for food or shelter. Other introduced animals like feral pigs and rusa deer also bother the parakeets. Hunting by humans does not seem to be a threat to the species anymore. Very few have been taken for the pet trade.

A disease called psittacine beak and feather disease was found in an echo parakeet in 1996. In 2004, there was a big outbreak. Later tests showed that more than 30% of tested birds had been exposed to the disease. Birds younger than two years old are most affected. 40–50% of young birds die from it and related infections each year. Some birds recover. But it's not known if they still carry the disease and pass it on to their young. The disease is also found in local rose-ringed parakeets. But it's not known which way it was first spread.

Images for kids

-

1770s illustration of the extinct Newton's parakeet, which was the closest relative of the echo parakeet