Quincy Adams Gillmore facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Quincy Adams Gillmore

|

|

|---|---|

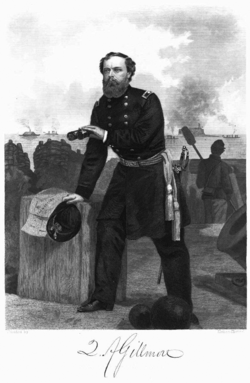

Civil War–era portrait of Gillmore

|

|

| Born | February 25, 1825 Black River (now Lorain), Ohio |

| Died | April 11, 1888 (aged 63) Brooklyn, New York |

| Allegiance | United States of America Union |

| Service/ |

United States Army Union Army |

| Years of service | 1849–1865 |

| Rank | |

| Commands held | X Corps |

| Battles/wars | American Civil War |

| Awards | Gillmore Medal |

Quincy Adams Gillmore (born February 25, 1825 – died April 11, 1888) was an American civil engineer. This means he designed and built things like roads, bridges, and forts. He was also an author and a general in the Union Army during the American Civil War.

Gillmore became famous for his actions at Fort Pulaski. He used new, powerful cannons called rifled artillery. These cannons easily broke through the fort's strong stone walls. This event showed that old stone forts were no longer safe against modern weapons. Gillmore became known around the world for planning siege operations. He also helped change how naval cannons were used in battle.

Contents

Early Life and Army Start

Gillmore was born in Black River, Ohio, which is now the city of Lorain. He was named after John Quincy Adams, who was about to become president when Gillmore was born.

In 1845, he started at the United States Military Academy in West Point, New York. He was a brilliant student and graduated first in his class of 43 in 1849. After graduating, he joined the engineers. He worked on building forts in Hampton Roads, Virginia, from 1849 to 1852. For the next four years, he taught military engineering at West Point. He even designed a new riding school there.

In 1856, Gillmore became a purchasing agent for the Army in New York City. He was promoted to captain in 1861.

Civil War Battles

Engineering on the Atlantic Coast

When the Civil War began in 1861, Gillmore joined General Thomas W. Sherman in Port Royal, South Carolina. He was promoted to brigadier general. Gillmore then led the attack on Fort Pulaski. He was a strong believer in the new rifled cannons used by the navy. He was the first officer to use them successfully to destroy an enemy stone fort.

During the short attack, more than 5,000 cannon shells hit Fort Pulaski. They were fired from about 1,700 yards away. The fort's walls broke, and it surrendered. This victory proved how effective the new cannons were.

The success in breaking a fort so strong and from such a distance brings great honor to General Gilmore's engineering skill and self-reliance. If he had failed, going against the advice of the army's best engineers, it would have ruined him. His success, which came from his talent, energy, and independence, deserves a great reward. —New York Tribune

Even though he was a very skilled engineer and artillery expert, his soldiers did not always like him.

Service in Kentucky

After a short time in New York City, Gillmore went to Lexington, Kentucky. There, he oversaw the building of Fort Clay, a fort on a hill overlooking the city. Gillmore then commanded a division in the Army of Kentucky. Later, he led the District of Central Kentucky.

Even though he was known for engineering and cannons, Gillmore's first independent command was leading a cavalry group. He fought against Confederate General John Pegram. Gillmore defeated the Confederates at the battle of Somerset. For this victory, he was promoted to colonel in the U.S. Army.

Return to the South

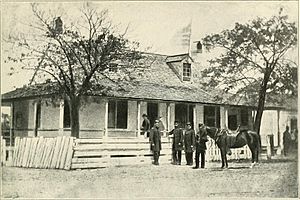

Gillmore took over command of the X Corps after General Ormsby M. Mitchel died. He also commanded the Department of the South. This area included North and South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida. His headquarters were at Hilton Head. Under his leadership, the army built two dirt forts in South Carolina: Fort Mitchel and Fort Holbrook.

He then focused on attacking Charleston, South Carolina. He had some success attacking Morris Island on July 10. This made Gillmore confident enough to attack Fort Wagner on the north end of the island. The next day, he launched the first attack on Fort Wagner, but it failed.

He gathered a larger force and planned a second attack with help from John A. Dahlgren's navy ships. On July 18, 1863, Gillmore's troops were pushed back with many losses in the Second Battle of Fort Wagner. Two of his commanders were killed, and another was wounded.

The Gillmore Medal

The Gillmore Medal is a special award from the United States Army. It was first given out on October 28, 1863. The medal is named after General Quincy A. Gillmore. He led Union troops trying to capture Fort Wagner in 1863 during the Civil War. This medal is also called the Fort Sumter Medal. It honors all Union soldiers who fought under General Gillmore's command around Charleston, South Carolina, in 1863.

Gillmore Integrates His Troops

Among the soldiers who attacked Fort Wagner was the 54th Massachusetts. This was a regiment of African-American soldiers. By law, they were led by white officers. General Gillmore ordered that his forces be integrated. This meant African-American soldiers were not just given simple chores. Instead, they carried weapons and fought in battles. Their brave attack on Fort Wagner was shown in the 1989 Civil War movie Glory.

The Swamp Angel Cannon

Gillmore decided to use a siege to capture Fort Wagner. He used new ideas like the 25-barreled Requa "machine gun". He also used a bright calcium flood light to blind enemies while his troops dug trenches. He also set up a huge Parrott rifle cannon. It was nicknamed the "Swamp Angel." This cannon fired 200-pound shots directly into the city of Charleston.

Even though the ground was swampy, Union troops managed to get closer to Fort Wagner. At the same time, Gillmore's cannons pounded Fort Sumter until it was destroyed. On September 7, 1863, Gillmore's forces finally captured Fort Wagner.

In February 1864, Gillmore sent troops to Florida. General Truman Seymour led them. Gillmore told Seymour not to go too far into Florida. But Seymour advanced toward Tallahassee, the state capital. He fought the largest battle in Florida, the Battle of Olustee. The Union forces lost this battle.

Virginia and Washington D.C.

In early May, Gillmore and the X Corps moved to Virginia. They took part in the Bermuda Hundred operations. They also played a big role in the terrible Drewry's Bluff battle. Gillmore openly argued with his boss, Benjamin F. Butler, about who was to blame for the defeat.

Gillmore asked to be moved and went to Washington, D.C.. In July 1864, Gillmore helped organize new soldiers and wounded veterans. He created a 20,000-man force. This force helped protect Washington, D.C., from 10,000 Confederates led by Jubal A. Early. Early's troops had reached the outer defenses of the capital. Union reinforcements were being moved from the Gulf Coast. Gillmore was put in charge of a group from the XIX Corps. This group was quickly sent to defend the capital at the battle of Fort Stevens.

End of the War

Once the threat to Washington was over, the XIX Corps moved to the Army of the Shenandoah. Gillmore was sent to the Western Theater to inspect military forts. As the war was ending, he was sent back to command the Department of the South one last time. He was in command when Charleston and Fort Sumter were finally returned to Union forces. He received special promotions to Brigadier General and Major General in the U.S. Army. These promotions were for his successful attacks against Battery Wagner, Morris Island, and Fort Sumter.

The war ended, and he left the volunteer army on December 5, 1865.

After the War

After the war, Gillmore returned to New York City. He became a well-known civil engineer. He wrote several books and articles about building materials, especially cement. Gillmore was part of the city's Rapid Transit Commission. This group planned elevated trains and public transportation. He also worked to improve the harbor and coastal defenses. He was a respected member of the University Club of New York.

Gillmore also did engineering work in other places. He helped rebuild forts along the Atlantic coast. Some of these were forts he had helped destroy during the war.

After his first wife died, he married the widow of former Confederate General Braxton Bragg. General Gillmore died in Brooklyn, New York, at age 63. His son and grandson, both named Quincy Gillmore, also became generals in the U.S. Army.

Remembering Gillmore

Some African Americans in the 1800s took the last name "Gillmore" or "Gilmore." This was to honor the general. For example, the traveling secretary for the Kansas City Monarchs baseball team was named Quincy J. Jordan Gilmore. The first name "Quincy" might have also come from him.

A coal schooner (a type of sailing ship) was named after him, called the General Q.A. Gillmore. It sank in 1881 in Lake Erie. This was about 45 miles west of Lorain, near Kelleys Island. The shipwreck is still in the shallow waters of the lake.

A second ship was also named after him, called the "Q.A. Gillmore." It was a steam-powered tugboat built around 1912–13. It worked on the Great Lakes and helped rescue ships during a big storm in 1913.

Books by Gillmore

- The Siege and Reduction of Fort Pulaski (1863)

- Engineer and artillery operations against the defences of Charleston harbor in 1863 (1865)

- The Strength of the Building Stones of the United States (1874)

- A Practical Treatise on Roads, Streets, and Pavements (1876)

- Limes, Hydraulic Cements, and Mortars

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Quincy Adams Gillmore para niños

In Spanish: Quincy Adams Gillmore para niños

| Percy Lavon Julian |

| Katherine Johnson |

| George Washington Carver |

| Annie Easley |