Bermuda Hundred, Virginia facts for kids

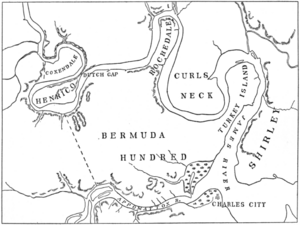

Bermuda Hundred was the first special area set up by the English in their Virginia settlement. It was started by Sir Thomas Dale in 1613, just six years after Jamestown. This important place was located where the Appomattox and James Rivers meet. For many years, Bermuda Hundred was a busy port town.

The name "hundred" came from an old English idea. It meant a large area of land that could support about 100 homes. The port at Bermuda Hundred was meant to serve not only its own area but also other "hundreds" nearby.

Later, during the American Civil War in May 1864, the land where Bermuda Hundred sits was part of the Bermuda Hundred Campaign. Today, Bermuda Hundred is no longer a big shipping port. It is a small community in Chesterfield County, Virginia.

Contents

- Early Days: The Mattica Village

- How Bermuda Hundred Was Started

- Where the Name "Bermuda Hundred" Came From

- John Rolfe and Tobacco Farming

- Growth in the Early Colonial Period

- Life in the Later Colonial Period

- French and Indian War and Before the Revolution

- The Revolutionary War Period

- After the Revolution and Before the Civil War

- The Civil War Period

- After the War and Modern Times

- First Baptist Church Bermuda Hundred

- Town of Bermuda Hundred Historic District

Early Days: The Mattica Village

Before the English arrived, the area of Bermuda Hundred was home to a Native American village called "Mattica." This village belonged to the Appomattoc people. A map from 1608 shows it clearly.

In May 1607, a group of English colonists led by Christopher Newport visited Mattica. The villagers welcomed them with food and tobacco. Newport noticed that the village was surrounded by fields of corn, which the Native Americans grew. A female leader, called a weroansqua, named Oppussoquionuske, was in charge of Mattica. Her brother, Coquonasum, led a larger village nearby.

Relations between the English and the Native Americans became difficult around 1609. This led to the First Anglo-Powhatan War in 1610. One summer, Oppussoquionuske invited some English settlers to her town. She tricked them into leaving their weapons behind, then had her men attack them. Most of the settlers were killed. In return, the colonists burned Mattica village. Oppussoquionuske was badly hurt and died that winter.

Around Christmas 1611, Sir Thomas Dale took over Oppussoquionuske's village and its farmland. He renamed it "New Bermudas."

How Bermuda Hundred Was Started

English settlers officially founded the town of Bermuda Hundred in 1613. It became an official town the next year. It was described as a fishing village located where the Appomattox and James Rivers meet.

Sir Thomas Dale, who was the Governor of Virginia for a few years, wanted to build a better settlement than Jamestown. He hoped to create a new main town a few miles from Bermuda Hundred, at a place called Henricus.

Dale first called the area across the Appomattox River from Bermuda Hundred "Bermuda Cittie." This place was later renamed Charles City Point, then City Point. In 1923, it became part of Hopewell, Virginia. Some people say Dale called the whole region "New Bermuda" after the island.

Where the Name "Bermuda Hundred" Came From

Bermuda Hundred got its name from the island of Bermuda. For a few years, Bermuda was also part of the Virginia Colony. This happened after a famous shipwreck in 1609.

The Sea Venture was a new ship carrying leaders and supplies for the Virginia Company of London. It was sailing to Jamestown as part of a large group of ships. They ran into a huge storm, possibly a hurricane. The Sea Venture started taking on water. After three days of fighting the storm, Admiral Sir George Somers purposely steered the ship onto a reef in uninhabited Bermuda. This saved all 150 people and a dog on board! Important people like the new Governor, Sir Thomas Gates, and John Rolfe (who later married Pocahontas) were among the survivors.

No one knew what happened to the Sea Venture for a year. The other ships reached Jamestown, bringing many new colonists but few supplies or leaders. This led to a terrible time at Jamestown called the "starving time" (1609-1610), where many colonists died from lack of food and supplies.

Meanwhile, the survivors on Bermuda used parts of their wrecked ship and local materials to build two new, smaller ships. Ten months later, most of them sailed to Jamestown. They left some men behind to claim Bermuda for England. Bermuda remained settled and was included in Virginia's boundaries in 1612. Later, in 1615, Bermuda became its own colony under a new company. Bermuda and Virginia stayed connected, and many places in North America are named after Bermuda.

John Rolfe and Tobacco Farming

John Rolfe was one of the people who survived the Sea Venture shipwreck and came to Virginia. At Bermuda Hundred, he started growing and selling different types of tobacco that were not native to the area. This tobacco became a very important product for the colony to export. Bermuda Hundred became a key shipping point for large barrels of tobacco grown on nearby plantations.

Rolfe became wealthy and lived in the Bermuda Hundred area for a while. He was likely living there during the terrible Indian Massacre of 1622. This attack by the Powhatan Confederacy killed many colonists and destroyed settlements like Henricus. Rolfe died in 1622, but it's not known if he was a victim of these attacks or died another way.

Growth in the Early Colonial Period

After winning battles in the Anglo-Powhatan wars, Bermuda Hundred was able to grow and develop. At first, it was a mix of a few medium-sized plantations, smaller farms, and a small port town. The town shipped goods from the farms and brought in supplies. This mix helped the community grow for most of the 17th century. The population slowly recovered from Native American attacks, and new colonists arrived.

However, in the second half of the 17th century, the demand for sugar and then tobacco grew hugely. This caused the countryside to change its crops. Also, Native Americans were pushed back, allowing plantations to become much larger. More people arrived, putting pressure on land and small farms.

Over time, farms switched to growing valuable but soil-depleting crops like sugar and tobacco. As the soil wore out, more land was needed. Large numbers of African slaves were brought in to work the land cheaply. This led to a few large plantations owning most of the land. Many smaller farms were bought by these plantations, and their owners either became dependent on the large landowners, moved to town, or went west for cheaper land.

Life in the Later Colonial Period

As the economy changed and grew, the port and town of Bermuda Hundred also expanded. At first, the port served both local river trade and ocean-going ships. But as large cash crops replaced local food crops, fewer farms meant less local trade. Also, as plantations grew, they needed bigger ships to carry their goods. At the same time, more farming led to more silt building up in the river, making the port shallower. This meant ships needed to be larger, but the port was getting harder for them to use.

Despite these challenges, the port still had many merchants. They traded with Great Britain and Ireland. Shippers also helped transport the growing number of settlers coming from Europe to the American colonies, many as indentured servants. Most of these new arrivals moved further west. The combination of trade, transporting settlers, and bringing in slaves made the merchant community in Bermuda Hundred thrive. The town's population grew.

By the time America became independent, the area was no longer a mix of small farms and businesses. It had become a quiet place with a few rich plantations and a port that was slowly getting smaller. Some original colonial families remained, but many new settlers arrived, including indentured servants. As slavery became more common, many working-class colonists moved away.

French and Indian War and Before the Revolution

By the 1760s, the dangers from Native American violence and economic problems in the Bermuda Hundred area had mostly gone away. This was thanks to British victories and better connections between Virginia and other British colonies. Even with some trade rules, the area was fully part of the British trading world. Many families sent their children to be educated in Britain and Ireland.

The merchant businesses had strong ties with other companies in the British Empire, and money was easy to get for improvements. The old plantation owners had become a powerful group who supported expanding westward. Many families on the frontier had originally come from older settlements like Bermuda Hundred. This helped keep colonial society connected.

However, a huge outbreak of Native American violence and war on the frontier deeply affected the Bermuda Hundred area, even though it wasn't directly attacked. The terrible losses on the frontier reminded people of the older Native American wars that almost destroyed the colony. Now, the battles were even bigger. The threat of the frontier collapsing and large French and Native American armies arriving made people fear total destruction. So, Bermuda Hundred played a big part in supplying weapons, men, officers, and materials for the war effort.

The war slowed down new British settlers and colonists from the Hundreds moving west. The horrors of the losses made people think twice about expanding further. More importantly, the British government broke its promises to settlers and plantation owners by not honoring recent treaties with Native American tribes. This led to the Proclamation of 1763. This proclamation was a secret agreement that took land and property from frontier settlers and stopped any further westward expansion of British colonies.

Economically, socially, and politically, the war, peace treaty, and proclamation greatly changed life in Bermuda Hundred. It stopped the area's growth. Before, the change from a mixed economy of small farmers and shippers to a commercial economy of planters and merchants had happened smoothly because there were new opportunities to move west. This relieved pressure on land, allowed smaller farmers to survive, made merchants rich, and kept the plantation owners wealthy.

But the proclamation and the halt to expansion threatened this way of life. Even worse, the government's actions caused political unrest in the Hundreds. Middle-class locals and frontier families started protesting against what they saw as the Crown's betrayal. The plantation owners debated how to react. Despite continued economic growth and more colonists arriving, the problems of a slave economy and global trade became clear.

Starting in the early 1700s, the population of European colonists in the Hundreds began to shrink. This was because of economic ideas that favored large businesses and the use of slavery. These factors pushed out many middle-class planters, farmers, merchants, and craftspeople, or made them move west for better chances. At first, indentured servants replaced them. Then, as slavery became dominant, cheap enslaved Black people replaced them, putting more pressure on the remaining working-class colonists to leave. Still, the area kept a slight majority of European colonists until just before the Revolutionary War.

By the time of independence, the area was no longer a mixed local economy. It was deeply connected to the larger Virginia Colony and the British Empire. For most of the remaining planters and townspeople in Bermuda Hundred, the answer was clear: they wanted to break away from the British Empire and declare independence, even if it meant economic losses. The French and Indian War had been a turning point for the colony.

The Revolutionary War Period

From the 1750s to the 1780s, wars on the frontier and the fight for independence temporarily stopped the population from shrinking. However, commercial activity and cash crop production were disrupted. Bermuda Hundred had become a quiet place with a few rich plantations and a slowly declining port. Some original colonial families remained, but new settlers and a growing number of enslaved Black people had changed the population mix. Still, many of the old colonial families kept their power in the Hundreds.

Despite their ties to Great Britain, the colonists in Bermuda Hundred were loyal to a larger American network. When independence was declared, many Americans joined the war effort. Bermuda Hundred planter families provided officers for the Virginia and Continental Army. At first, British forces did not invade the region. However, British ships made raids along the coast of Bermuda Hundred, burning houses believed to belong to American patriots. While most people fought for the Americans, some were Loyalists, and their plantations were also destroyed.

These small battles changed when a combined British force arrived under General Charles Cornwallis, 1st Marquess Cornwallis. His plan to defeat the Americans had been set back in the southern states. He decided to join forces with another British army in Virginia.

In March 1781, General George Washington sent Marquis de Lafayette to defend Virginia. Lafayette had 3,200 men, but the British had 7,200. The British quickly pushed aside the local militia in Bermuda Hundred. Lafayette avoided a major battle while gathering more troops. Cornwallis received orders to build a fortified naval base on the Virginia Peninsula.

By marching down the Tidewater and occupying Bermuda Hundred to follow these orders, Cornwallis put himself in a trap. General Washington moved quickly and secretly from New York City, New York, and the French fleet arrived under the Comte de Grasse. The combined French-American army surrounded Cornwallis. After the British navy was defeated by the French at the Battle of the Chesapeake, Cornwallis was trapped. He surrendered to General Washington and the French commander on October 19, 1781. Cornwallis claimed to be sick and sent another general to surrender his sword.

After the Revolution and Before the Civil War

The French and Indian Wars and the Proclamation of 1763 had temporarily slowed people from leaving Bermuda Hundred for the west. But after independence, this changed. The defeat of Native Americans on the frontier and the opening of western roads allowed more and more people from Bermuda Hundred to move west for new opportunities.

Also, the rural economy suffered. The land was worn out from farming, and plantations lost income from the war. Many grand plantation houses were ruined. Their old trade ties with the British Empire were broken, war debts were huge, and the economy was in chaos. Money was scarce for plantation owners. Many old families either joined other planters, moved west, or were forced out for being Loyalists.

However, those who survived found a new chance when the slave trade was abolished. This made the value of enslaved people go up. So, while their land recovered, planters sold off extra enslaved people to newer plantations in the west and southwest. This helped them pay off war debts, rebuild some houses, and keep their wealth.

Despite these challenges, the rural plantation economy survived. Tenant farmers and a few independent farmers grew food for local people. As income recovered, most remaining white rural and working-class people found jobs as laborers, overseers, skilled workers, or civil servants. They earned money by supporting the plantations and government.

The town and port faced similar problems. The war had badly hurt the economy. Trade with Great Britain and Ireland was destroyed. New trade restrictions were placed on the young American nation. The Napoleonic wars further slowed international trade. British and Irish migration stopped for about 30 years, and later migrants went to other ports. The end of the American slave trade also cut much of the port's business. At the same time, worn-out soil limited crop production, further reducing trade in town.

Yet, as the new nation recovered and focused on domestic trade, the economy began to improve in the Tidewater region. The continued presence of planters and farmers created demand for goods. Local and domestic shipping, especially with New England, replaced trade with the British Empire. These trade routes favored smaller boats, which were easier to build and maintain in small ports like Bermuda Hundred. Other parts of the bay also saw a return to farming and fishing, which benefited the small port.

Eventually, a balance was reached. Most of the remaining white rural community lived a comfortable life, growing food and selling extra crops to local towns and plantations. They also worked part-time on plantations and in towns for extra income. Slowly, starting in the 1820s, parts of the Hundreds returned to crop production, and most of the land was in use by the 1850s.

So, while not as grand as in early colonial times, the planter families, small farmers, and boat owners continued their peaceful and somewhat prosperous lives before the Civil War. They were supported by a small but skilled group of artisans, prosperous merchant families, and a larger, poorer white working class. A large population of enslaved and free Black people also lived in the countryside. The planter class, like those in Bermuda Hundred, continued to hold social and political power in Virginia and the country. In fact, by the time of the Civil War, they provided many of the country's top military and political leaders.

The Civil War Period

When the Civil War began, Bermuda Hundred and its surrounding area had become a quiet, less important place. Some original plantations were falling apart, reminders of a time when the area was central to Virginia's economy. However, several country estates still stood, like Presquile, Mont Blanco, and Meadowville, along with large plantations nearby such as Shirley and Appomattox. Independent farmers, who had gained wealth from local sales, also earned money from smaller cash crops. Smaller part-time farmers, overseers, and tenant farmers lived in the countryside in well-built brick homes. Other Virginians worked as laborers on farms and in towns. The large Black population lived a restricted life on the plantations.

In the town, the exciting days of merchant adventures were long gone. Merchants mostly acted as agents for the remaining farms. Still, these merchant families earned good money trading valuable cotton, tobacco, and other crops within the state, nation, and internationally. This gave them a good understanding of world events. A community of fishermen also worked the Chesapeake Bay, alongside artisans, craftspeople, boat builders, and small freight shippers.

The War of Independence was still fresh in people's minds. The issues seemed similar to them, and most made arguments like those during the Revolution. They worried that the growing power of the Republican Party in the North threatened their homes, the right of independent farmers to own their land, and most importantly, that the idea of ending slavery was being discussed. Many families still had members who had fought in the Revolution, and their grandchildren now led the debates. People had sacrificed their wealth for their beliefs, and despite the odds, these families pledged their fortunes again. They were seen as rightful leaders by the working and farming classes in the South.

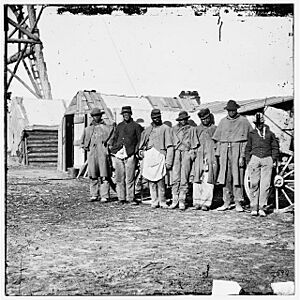

With the war, the area was fully involved in the war effort. As chaos spread, the Union navy blockaded the port. Many small shipping boats were captured, destroyed, or fell into disrepair. Those that remained were used as blockade runners to sneak past Union ships. Also, a worrying number of enslaved people began to escape. More and more white men volunteered for the Confederate Army. Most of the planter class became officers, and many were killed in battles. Soon, the old and young were put to work defending the countryside from escaped slaves and Union raiding parties. Eventually, the remaining white population formed a local militia, helped by veterans, as a large Union army arrived.

The region was severely damaged during the Civil War, especially during the Bermuda Hundred Campaign. This was a series of battles fought near the town in May 1864. Union General Benjamin Butler tried to attack Richmond from the east but was stopped by Confederate forces. The Confederates built a strong defense line that trapped Butler's army on the Bermuda Hundred peninsula. This campaign was one of the last Confederate victories, and General Butler was moved to another command.

After the War and Modern Times

The war and the campaign ruined the fortunes of the planter class. Many families, both rich and poor, were wiped out. The battles destroyed or heavily damaged much of the countryside's buildings and homes. The number of enslaved Black people dropped sharply due to escapes during the war and later emancipation. The destruction of the plantation economy also hurt the small white communities in the countryside. These white laborers, overseers, skilled workers, and civil servants had earned money by supporting the plantations and government. After the war and during Reconstruction, these white families faced unemployment. As a result, along with many of the former enslaved people, they became very poor, often working as sharecroppers. Others moved to the small town or left the area. Bermuda Hundred never regained its earlier population levels.

In the town, buildings were also damaged. Much of the valuable equipment was taken by the Union Army. This included tools for building and repairing boats or making crafts. After the war, the town's population temporarily grew as many people from the countryside moved in, putting pressure on resources. With many boats lost, the fishing and small freight businesses were permanently wiped out. Without money to stop silting or to dredge, the port's ability to handle ship traffic decreased even more.

Unable to ship their crops, the planter class tried to find other ways to transport goods and rebuild the economy, especially through railroads. Even though they had lost their wealth, the planters and merchants still held political power. During the difficult time of Reconstruction, some managed to bring money into the area to build new railways.

After the Civil War, the Brighthope Railway in Chesterfield county was rerouted to Bermuda Hundred. It was extended west and became a narrow gauge railroad. The Brighthope Railway went bankrupt and became part of the Farmville and Powhatan Railroad, later called the Tidewater and Western Railroad. This railroad went to Farmville. While it helped the farming community avoid total loss, it didn't bring back the financial success of the planter class.

The Great Depression of 1873 and later farming problems, along with the rise of Egyptian cotton and Indian cotton, pushed aside American cotton. This had been the source of the planter class's wealth. Although this reduced demand and forced a switch to crops like corn and wheat (which helped the soil health), the new crops didn't bring enough wealth or traffic for growers, merchants, or the railroad. Still, growers experimented with different crops and farming methods, eventually earning good income from tobacco in later decades. The number of plantations never recovered. However, some sharecroppers and tenant farmers actually managed to become independent farmers. But economic setbacks and competition kept the narrow gauge railroad from bringing back the prosperity seen before the war. Ironically, it did help the area return to its 17th-century mixed economy, allowing the region to survive and grow slowly.

In the town, much like the countryside, the war caused economic losses that lasted for one or two generations. By the time some of the planter class had rebuilt their farms, trade networks, and crop production, the country and world had changed a lot. They never regained their former wealth from the land, and many lost or sold their property. As a result, the railroad and merchant businesses barely made a profit for sixty years, and the town's waterway shipping business suffered. The town never recovered its merchant sector, slowly becoming a small fishing village and local harbor. Eventually, the railroad and port facilities were mostly abandoned by the Great Depression, leaving the town a shadow of its former self.

Today, the town of Bermuda Hundred is home to about four main families: the McWilliams, the Hewletts, the Johnsons, and a Gray family. In the 1980s, Phillip Morris opened a Tobacco Processing facility there. An Allied Signal plant and an industrial facility operated by Imperial Chemical Industries soon followed. In 1990, the Varina-Enon Bridge opened, connecting the area to Richmond via Interstate 295. By the early 2000s, most of the remaining farms and former plantations in Bermuda Hundred, like Presquile, Mount Blanco, and Meadowville, had been sold for commercial or residential development. A part of the Presquile farm is now the Presquile National Wildlife Refuge, a protected area for wildlife.

First Baptist Church Bermuda Hundred

The First Baptist Church Bermuda Hundred was built around 1850 in the Greek Revival style. It has a classic, balanced front with three sections and a pointed roof. It stands on land that used to be the market square of the town. This land was also home to earlier churches from the 1600s.

Unlike many churches in the area, this church originally welcomed both Black and white people, and both rich and poor. This was probably because many free and enslaved Black families had lived in the area for a long time. However, the church was still segregated. Enslaved and free blacks had to sit in the balcony, while white people sat in the lower area. Over time, more poor and working-class white church members meant some white people also had to sit in the balcony, which caused some unhappiness.

Before the Civil War, some white members left to join the Southern Baptists, who separated from the national church over the issue of slavery. These members formed the Enon Baptist Church nearby. The historic First Baptist Church was then led by its strong free Black congregation. Several Black Baptist churches in Chesterfield County and Hopewell today can trace their beginnings back to this free Black congregation at First Baptist.

Town of Bermuda Hundred Historic District

|

Town of Bermuda Hundred Historic District

|

|

Houses east of the Methodist church

|

|

| Lua error in Module:Location_map at line 420: attempt to index field 'wikibase' (a nil value). | |

| Location | Both sides of Bermuda Hundred and Allied Rds. |

|---|---|

| Area | 16.2 acres (6.6 ha) |

| Built | 1613 |

| MPS | Prehistoric through Historic Archeological and Architectural Resources at Bermuda Hundred MPS |

| NRHP reference No. | 06001011 |

Quick facts for kids Significant dates |

|

| Added to NRHP | November 8, 2006 |

The Town of Bermuda Hundred Historic District is a special area recognized for its history. It includes 14 important buildings, 1 historic site, and 1 historic object. It is located on both sides of Bermuda Hundred and Allied Roads in Chester, Virginia.

This district was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2006.

| Isaac Myers |

| D. Hamilton Jackson |

| A. Philip Randolph |