Ragnall mac Somairle facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Ragnall mac Somairle |

|

|---|---|

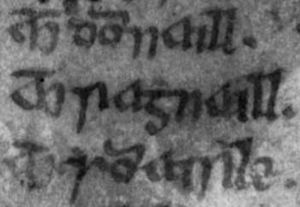

Ragnall's name in an old book called the Chronicle of Mann

|

|

| Spouse | Fonia |

| Issue | Ruaidrí, Domnall |

| Dynasty | Clann Somairle |

| Father | Somairle mac Gilla Brigte |

| Mother | Ragnhildr Óláfsdóttir |

Ragnall mac Somairle was an important leader in Scotland during the late 1100s and early 1200s. He lived on the western coast of Scotland. Ragnall was likely a younger son of Somairle mac Gilla Brigte, who was a powerful Lord of Argyll. His mother was Ragnhildr, whose father was Óláfr Guðrøðarson, the King of the Isles.

The Kingdom of the Isles was a mix of Norse-Gaelic cultures. It was ruled by Ragnall's father and his mother's father. This kingdom was next to the growing Kingdom of Scots. In the mid-1100s, Somairle became very powerful. He took control of the Kingdom of the Isles from his brother-in-law.

After Somairle died in battle in 1164, his kingdom was probably split among his sons. Ragnall likely received lands in the southern Hebrides and Kintyre. Over time, Ragnall grew stronger. He became the main leader of his family, known as the meic Somairle. Ragnall even called himself "King of the Isles, Lord of Argyll and Kintyre." He also used the title "Lord of the Isles." His claim to be king came from his mother, Ragnhildr, who was part of the Crovan dynasty.

Ragnall is not mentioned in records after his brother Áengus defeated him and his sons. We do not know exactly when Ragnall died. It could have been between 1191 and 1227. Records show that Ragnall was a big supporter of the Church. While his father followed older Christian traditions, Ragnall supported newer religious groups from Europe. Ragnall's seal, which showed a knight on horseback, also suggests he wanted to appear as a modern ruler, like the leaders in the nearby Kingdom of Scots.

Ragnall had two sons, Ruaidrí and Domnall. They later started important families in the Hebrides. Ragnall or Ruaidrí also had daughters. These daughters married Ragnall's cousins, Rǫgnvaldr and Óláfr. Both of these cousins were kings of the Crovan dynasty in the 1200s.

Contents

Ragnall's Family History

Ragnall was a son of Somairle mac Gilla Brigte (who died in 1164). His mother was Ragnhildr, daughter of Óláfr Guðrøðarson, the King of the Isles. Somairle and Ragnhildr had at least three sons: Dubgall, Ragnall, and Áengus. Dubgall seems to have been the oldest.

We don't know much about Ragnall's father's early life. But his marriage shows he came from an important family. In the early 1100s, the Hebrides and the Isle of Man were part of the Kingdom of the Isles. This kingdom was ruled by Ragnall's grandfather, Óláfr. Somairle's rise to power might have started around this time. Records suggest that Argyll may have been slipping from the control of David I, King of Scots.

Somairle first appears in records in 1153. He joined a rebellion against the new Scottish King, Máel Coluim IV. In the same year, Somairle's father-in-law, Óláfr, was killed. Óláfr had ruled the Kingdom of the Isles for about 40 years. Óláfr's son, Guðrøðr, took over.

Later, Somairle tried to take control of the kingdom. He put his son Dubgall forward as a possible king. Somairle and his brother-in-law, Guðrøðr, fought a sea battle in 1156. After this, Somairle seemed to control much of the Hebrides. Two years later, he defeated Guðrøðr and took over the whole island kingdom.

In 1164, Somairle fought the King of Scots again. He led a huge army from the Isles, Argyll, and Kintyre. Somairle's forces sailed up the River Clyde. They landed near what is now Renfrew. There, the Scots defeated them, and Somairle was killed. After Somairle's death, Guðrøðr returned to the Isles. He took control of Mann. But Somairle's family, the meic Somairle, kept the Hebridean lands he had won in 1156.

Records don't say how Somairle's lands were divided. But it's likely his territory was split among his sons. The exact borders are unknown. It's possible their lands stretched from Glenelg in the north to the Mull of Kintyre in the south. Áengus might have ruled in the north. Dubgall might have been in Lorne. Ragnall probably had Kintyre and the southern islands.

Family Fights

We don't know much about Somairle's sons in the years after his death. Dubgall is first mentioned in 1175, far from the Isles. It's possible that by the 1180s, Ragnall started taking over Dubgall's lands. Ragnall might have become the new head of the meic Somairle family.

In 1192, the Chronicle of Mann says that Ragnall and his sons were defeated in a very bloody battle against Áengus. The book doesn't say where the battle happened or why. But it might have been in the northern part of the meic Somairle lands. This fight could have been because Ragnall was gaining power. It might also mark Ragnall's downfall.

Ragnall gave land to a monastery called Paisley Priory. This gift probably happened after his defeat by Áengus. It might show that Ragnall tried to make an alliance with Alan fitz Walter, a powerful Scottish leader. Alan's family supported Paisley Priory. They were expanding their power westwards from Renfrew.

The island of Bute seems to have come under Alan's control around this time. Alan might have used the family fights among the meic Somairle to take the island. Or Ragnall might have given him the island for military help against Áengus. Alan's growing power outside Scotland might have worried William I, King of Scots (who died in 1214). This could explain why the king built a royal castle at Ayr in 1195. This castle helped the Scottish king control the area. It was meant to control both his own nobles and independent rulers nearby. Alan's expansion stopped around 1200. This might have been because the king was worried about Alan's alliance with Ragnall.

Titles and Seals

A royal inspection in 1508 showed that Ragnall called himself "King of the Isles, Lord of Argyll and Kintyre" in a Latin document. This title might mean he claimed all his father's lands. In a later document, Ragnall called himself "Lord of the Isles" when giving land to Paisley Priory.

Ragnall might have stopped using "king" and started using "lord" because of his defeat by Áengus. Or it could be because his cousin, Rǫgnvaldr Guðrøðarson, the King of the Isles, was becoming more powerful. The title "Lord of the Isles" was later used by Ragnall's great-great-grandson, Eoin Mac Domhnaill, in 1336.

Ragnall's gift to Paisley Priory is known from two documents. One is from the late 1100s or early 1200s. A later copy is from 1426. This later document describes a seal that was said to be Ragnall's. On one side, the seal showed a ship full of armed men. On the other side, it showed a man on horseback with a sword.

Ragnall is the only one of Somairle's sons known to have called himself "King of the Isles." His use of this title and his seal were probably copied from the powerful Crovan dynasty leaders. For example, his cousin Rǫgnvaldr used the same title and had a similar two-sided seal. The seals of both cousins showed a Norse-Gaelic galley (a type of ship) and an Anglo-French knight. The ship showed their power over an island kingdom. The knight showed their connection to feudal society and the idea of knighthood. Using such seals helped these Norse-Gaelic lords appear modern to their neighbors in England and Scotland.

Church Activities

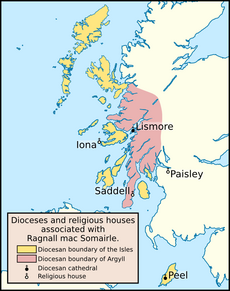

The church area in Somairle's kingdom was the large Diocese of the Isles. In the mid-1100s, this area became part of the new Norwegian Archdiocese of Nidaros. This meant the church's borders and its connection to Norway matched the Kingdom of the Isles. But by the late 1100s, a new church area, the Diocese of Argyll, started to appear. This happened during the ongoing fights between the meic Somairle and the Crovan dynasty.

In the early 1190s, the Chronicle of Mann says that Cristinus, the Bishop of the Isles, was removed. He was from Argyll and probably supported the meic Somairle. Michael, a Manxman, replaced him. Michael seemed to be supported by Rǫgnvaldr. Cristinus had been bishop for at least 20 years, during a time when the meic Somairle were powerful. His removal happened when the Crovan dynasty, under Rǫgnvaldr, became strong again. Rǫgnvaldr had become king in 1187. He seemed to take advantage of the fights among the meic Somairle, and maybe even Ragnall's downfall.

The first known Bishop of Argyll, Haraldr, was active in the early 1200s. But there were probably earlier bishops we don't know about. The Diocese of Argyll is first mentioned in a Papal document from the late 1100s. It's possible Cristinus, or someone else, was the first bishop of this new area. Cristinus's time as bishop might have seen a shift in church focus towards Argyll.

The new Diocese of Argyll was outside Rǫgnvaldr's direct control. This allowed the meic Somairle to support the church without his interference. The large size of the Diocese of the Isles might have caused some areas to break away. This led to its eventual split. Parts of the new diocese might have also come from other Scottish church areas. The Scottish king might have liked the new diocese. It could have helped him extend his power into the region. But the meic Somairle rulers were against the Scots. The main church of the new diocese, on Lismore, was far from the Scottish king's control. The creation of the Diocese of Argyll was a long process. It was likely not just the work of one person. Even though the early diocese often had no bishop, it eventually became strong. This allowed the meic Somairle to keep local control over church power.

Iona Abbey and Nunnery

In the 500s, an Irish monk named Colum Cille started a monastery on Iona. From there, he set up many other monasteries in the islands and mainland. His chosen followers, often from his own family, managed these places. Over time, a network of monasteries, called an "ecclesiastical familia," grew around Iona. During Viking attacks in the 800s, the leaders of this network moved to Kells. In the 1100s, the leader moved to Derry.

In 1164, when Somairle ruled the Kingdom of the Isles, he tried to bring the monastic network back to Iona. But this idea faced a lot of opposition. With his death in the same year, his plans to control the kingdom and the church failed.

About 40 years after Somairle's death, a Benedictine monastery was built on Iona. The document for its founding is from December 1203. This suggests Ragnall might have built it, as old stories say. But there's no strong proof directly linking him to its founding. The document shows the monastery received many gifts from across the meic Somairle lands. This means other important family members, like Dubgall or his son Donnchad, probably supported it.

The monastery was placed under the protection of Pope Innocent III. This made it independent from the Diocese of the Isles. But to get this protection, they had to follow the Benedictine Rule. This replaced the old traditions of Colum Cille.

The meic Somairle's decision to bring Benedictines to Iona was very different from Somairle's own actions. It caused a strong and violent reaction from Colum Cille's old monastic family. In 1204, after the new monastery was built, a large group of Irishmen came to Iona. They burned the new buildings to the ground. An old poem shows how upset Colum Cille's followers were. They felt their rights were violated and cursed the meic Somairle. But the Benedictines stayed on Iona. The old monastery of Colum Cille was almost completely replaced. If Ragnall was behind the Benedictine monastery, it might show he was following his father's path. He was asserting himself as a king in the Isles.

An Augustinian nunnery was built south of the monastery sometime before the late 1100s or early 1200s. Old stories say Ragnall founded it. They also say his sister, Bethóc, was the first leader (prioress) there. While the story that it was a Benedictine nunnery is wrong, the idea that Bethóc was a "religious woman" is supported by an old stone on the island. This stone had an inscription in Gaelic about "Behag nijn Sorle vic Ilvrid priorissa." So, Ragnall might have founded the nunnery, and his sister could have been its first prioress. Like the abbey, the nunnery's ruins show Irish influences. This suggests the Augustinian nunnery had connections to Ireland.

Iona is famously known as the burial place of Scottish kings. But evidence for this only goes back to the 1100s or 1200s. These stories seem to have been created to make Iona seem more important as a royal burial site. The meic Somairle might have encouraged this. Iona was definitely the burial place for Ragnall's later family members and other important leaders from the West Highlands.

The oldest building still standing on Iona is St Oran's Chapel. Its architecture shows some Irish influences. It is thought to be from the mid-1100s. Ragnall's later family used this chapel as a burial place. It's possible Ragnall or his father built it. But it could also have been built by the Crovan dynasty kings. For example, Guðrøðr, who was buried on the island in 1188, or his father Óláfr.

Saddell Abbey

A member of the meic Somairle, possibly Ragnall or his father, might have founded Saddell Abbey. This was a small Cistercian monastery in the heart of the meic Somairle lands. This ruined monastery was the only Cistercian house in the West Highlands. Evidence from the monastery suggests Ragnall was probably the founder. For example, when the monastery's documents were confirmed by Popes and Scottish Kings, Ragnall's grant was the earliest one. Also, confirmations from 1393 and 1508 specifically say Ragnall was the founder. Old family stories also support this. However, some evidence suggests Somairle was the founder. A French list of Cistercian houses from the 1200s mentions "Sconedale" in 1160.

It's possible that Somairle started planning a Cistercian monastery at Saddell. But Ragnall might have been the one who gave it its first gifts of land and money. Somairle tried to bring Colum Cille's old monastic family back to Iona. This was at a time when Cistercians were already in Ireland and the Isles. This might mean Somairle preferred older Christian traditions. But his sons, especially Ragnall, were open to these newer European religious groups.

Somairle fought against the Scots and died invading Scotland. This could suggest that Ragnall's church activities were partly to improve relations with the King of Scots. Also, in those days, leaders often built monasteries to show their wealth and power. Ragnall's foundations and gifts might have been a way to show himself as a modern ruler.

Death

We don't know exactly when or how Ragnall died. Old family stories say he died in 1207. But there's no other proof for this date. These old stories can be unreliable. For example, they get Somairle's death date wrong by 16 years. If Ragnall's death date is also off by 16 years, he might have died in 1191. If so, his death might be linked to his defeat by his brother. However, the Chronicle of Mann, which talks about the 1192 fight, doesn't mention Ragnall dying then. Another idea is that Ragnall might have been killed around 1209 or 1210. This was during more family fighting among the meic Somairle.

A closer look at the old family stories suggests Ragnall might have died in 1227. But this date might be too late for someone who was an adult by 1164. Ragnall's gift to Paisley Priory might give us clues. His document is similar to one given by his son, Domnall. This might mean they were made around the same time. If so, Ragnall's document could mean he survived his defeat by Áengus. Both documents might suggest Ragnall was nearing the end of his life. Ragnall's gift might also mean he joined the monks at Paisley. If he gave the gift near the end of his life, he might have spent his final days there. Since the priory was founded by the meic Somairle, his possible retirement there could explain why he disappears from records after 1192.

Family and What He Left Behind

Ragnall's wife was named "Fonia." This name might be a Latin way of writing the Gaelic name Findguala. Old Hebridean stories say Ragnall married "MacRandel's daughter." This story is likely wrong because of the dates. But it's possible it refers to an earlier leader. If so, Ragnall's son, Domnall, might have been named after a son of an earlier earl.

Ragnall had two sons: Ruaidrí (who died around 1247) and Domnall. Domnall's family line, the meic Domnaill, became the powerful Lords of the Isles. They ruled the entire Hebrides and large mainland areas from the 1300s to the late 1400s. Ruaidrí started the meic Ruaidrí family, a less known group who lived in Garmoran. Ruaidrí seems to have been the older of Ragnall's sons. He is first mentioned by name in 1214. Four years before that, Áengus and his sons were killed on Skye. This record could mean that Áengus had taken over from Ragnall. Then Ragnall's sons killed Áengus's family, and Ruaidrí took control of the meic Somairle.

It's very likely that Ragnall or Ruaidrí had daughters who married Rǫgnvaldr and his younger half-brother, Óláfr Guðrøðarson. An old book says Rǫgnvaldr married "Lauon," the daughter of a nobleman from Kintyre. She was also the sister of his own (unnamed) wife. We don't know exactly who this father-in-law was. But historical records link Ragnall's family with Kintyre more than any other area. Both Ragnall and Ruaidrí were called "Lord of Kintyre." The first marriage might have happened before 1210. These marriages seem to have been planned to fix relations between the meic Somairle and the Crovan dynasty. These two families had fought for control of the Isles for about 60 years. It's possible that Ruaidrí, the main leader of the meic Somairle, formally recognized Rǫgnvaldr as king. This would have made Ruaidrí an important leader in a reunited Kingdom of the Isles.

Ragnall is mainly remembered in later Hebridean stories as the link between Somairle and Domnall's descendants. Old family stories say Ragnall was "the most distinguished of the Gall or Gaedhil for prosperity, sway of generosity, and feats of arms." They also say he "received a cross from Jerusalem." This might mean Ragnall went on a pilgrimage or a crusade. While this is possible, no other old records confirm it.

A description of the Hebrides from the mid-1500s shows that Ragnall's rule was still remembered then. In this account, Donald Monro said Ragnall created the law code used by Hebridean leaders hundreds of years later.

| Valerie Thomas |

| Frederick McKinley Jones |

| George Edward Alcorn Jr. |

| Thomas Mensah |