Jean-Philippe Rameau facts for kids

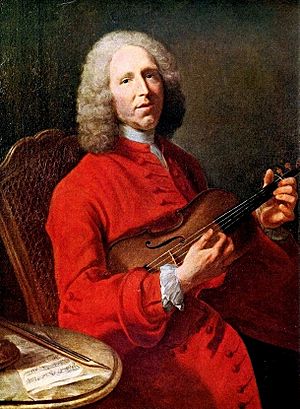

Jean-Philippe Rameau (born September 25, 1683 – died September 12, 1764) was a famous French composer and music theorist. He is seen as one of the most important French musicians of the 1700s. Rameau took over from Jean-Baptiste Lully as the main composer of French opera. He was also the best French composer for the harpsichord during his time, along with François Couperin.

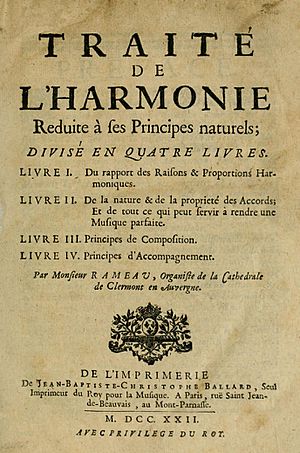

Not much is known about Rameau's early life. He became famous in the 1720s for his book Treatise on Harmony (1722). He also wrote amazing harpsichord music that was played all over Europe. Rameau was almost 50 years old when he started writing operas. Today, he is mostly known for these operas.

His first opera, Hippolyte et Aricie (1733), caused a big stir. People who liked Lully's music strongly disliked it. They thought Rameau's use of harmony was too new and different. Still, Rameau soon became the top French opera composer. Later, in the 1750s, he was seen as an "old-fashioned" composer. This happened during a debate called the Querelle des Bouffons, where people preferred Italian opera.

Rameau's music went out of style by the late 1700s. It was not until the 1900s that people started to bring it back. Today, his music is enjoyed again. More and more of his works are being performed and recorded.

Contents

Rameau's Life Story

We do not know much about Rameau's life. This is especially true for his first 40 years. He moved to Paris for good later in life. Rameau was a private person. Even his wife did not know much about his early life. This is why there is not much information about him.

Early Years (1683–1732)

Rameau's early life is not well known. He was born on September 25, 1683, in Dijon, France. He was baptized on the same day. His father, Jean, was an organist in churches around Dijon. His mother, Claudine Demartinécourt, was a notary's daughter. Jean-Philippe was the seventh of their eleven children.

Rameau learned music before he could read or write. He went to a Jesuit school in Dijon. But he was not a good student. He would often disrupt classes by singing. He later said his love for opera began at age twelve. Rameau was supposed to study law. However, he decided he wanted to be a musician. His father sent him to Italy, where he stayed a short time in Milan.

When he came back, he worked as a violinist. He played with traveling groups. Then he became an organist in churches in different towns. After this, he moved to Paris for the first time. In 1706, he published his first known music. These were harpsichord pieces in his book Pièces de Clavecin. They showed the influence of his friend Louis Marchand.

In 1709, Rameau moved back to Dijon. He took over his father's job as an organist. His contract was for six years. But Rameau left early. He took similar jobs in Lyon and Clermont-Ferrand. During this time, he wrote motets for church services. He also composed secular cantatas.

In 1722, he returned to Paris for good. There, he published his most important music theory book, Traité de l'harmonie (Treatise on Harmony). This book quickly made him famous. In 1726, he published another book, Nouveau système de musique théorique. He also published two more collections of harpsichord pieces in 1724 and 1729 (or 1730).

Rameau first tried writing music for the stage. The writer Alexis Piron asked him to write songs for his popular plays. They worked together four times, starting with L'endriague in 1723. Sadly, none of this music has survived.

On February 25, 1726, Rameau married Marie-Louise Mangot. She was 19 years old. She came from a musical family and was a good singer. They had four children, two boys and two girls. Their marriage was said to be a happy one. Even though he was famous for his music theory, Rameau had trouble finding an organist job in Paris.

Later Years (1733–1764)

Rameau was almost 50 when he decided to write operas. This is what he is most famous for today. He had tried to get a libretto (the words for an opera) from writer Antoine Houdar de la Motte in 1727, but nothing happened. He was finally inspired to try the important tragédie en musique style. This happened after he saw Montéclair's Jephté in 1732.

Rameau's opera Hippolyte et Aricie opened on October 1, 1733. It was quickly seen as the most important French opera since Lully died. But it also caused arguments. Some people, like composer André Campra, were amazed by its new ideas. Others found its harmonies too strange. They saw it as an attack on French music traditions. The two groups, called Lullyistes and Rameauneurs, argued about it for years.

Around this time, Rameau met Alexandre Le Riche de La Poupelinière. He was a powerful financier who became Rameau's supporter until 1753. La Poupelinière's girlfriend, Thérèse des Hayes, was Rameau's student. She loved his music. In 1731, Rameau became the conductor of La Poupelinière's private orchestra. It was a very good orchestra. Rameau held this job for 22 years.

La Poupelinière's home helped Rameau meet important people. These included Voltaire, who soon started working with Rameau. Their first project, the opera Samson, was stopped. This was because an opera on a religious topic by Voltaire, who often criticized the Church, would likely be banned.

Meanwhile, Rameau brought his new music style to a lighter opera type. This was the opéra-ballet. His Les Indes galantes was very successful. He then wrote two more tragédies en musique: Castor et Pollux (1737) and Dardanus (1739). Another opéra-ballet, Les fêtes d'Hébé, also came out in 1739. All these operas from the 1730s are among Rameau's best works.

However, Rameau then stopped composing for six years. The only work he produced was a new version of Dardanus (1744). We do not know why he stopped writing music during this time. Perhaps he had a disagreement with the opera authorities.

The year 1745 was a big moment for Rameau. He received several requests from the royal court. These were for works to celebrate France's win at the Battle of Fontenoy. They also celebrated the marriage of the Dauphin to Infanta Maria Teresa Rafaela of Spain. Rameau wrote his most important comic opera, Platée. He also worked with Voltaire on two pieces: the opéra-ballet Le temple de la gloire and the comédie-ballet La princesse de Navarre.

These works brought Rameau official recognition. He was given the title "Composer to the King's Cabinet." He also received a good pension. 1745 also marked the start of a bitter feud between Rameau and Jean-Jacques Rousseau. Rousseau is known today as a thinker. But he also wanted to be a composer. He had written an opera, Les muses galantes. Rameau was not impressed by it.

Later in 1745, Voltaire and Rameau asked Rousseau to change La Princesse de Navarre into a new opera. It was called Les fêtes de Ramire. Rousseau then claimed they stole his work. However, music experts have found almost none of Rousseau's music in the piece. Still, Rousseau held a grudge against Rameau for the rest of his life.

Rousseau was a key person in the second big argument about Rameau's work. This was the Querelle des Bouffons (1752–54). It compared French tragédie en musique with Italian opera buffa. This time, Rameau was called old-fashioned. His music was seen as too complex. People preferred the simple style of works like Pergolesi's La serva padrona.

In the mid-1750s, Rameau criticized Rousseau's writings on music in the Encyclopédie. This led to arguments with leading thinkers like d'Alembert and Diderot. Because of this, Jean-François Rameau became a character in Diderot's book, Le neveu de Rameau (Rameau's Nephew).

In 1753, La Poupelinière started a relationship with a musician named Jeanne-Thérèse Goermans. Her husband pushed her to be with the rich financier. She convinced La Poupelinière to hire the composer Johann Stamitz. Stamitz took over from Rameau after Rameau and his patron had a falling out. But by then, Rameau no longer needed La Poupelinière's money.

Rameau kept working as a theorist and composer until he died. He lived with his wife and two children in a large home in Paris. He would often go for walks alone, deep in thought. Sometimes he met the young writer Michel Paul Guy de Chabanon. Chabanon wrote down some of Rameau's sad comments. Rameau said, "Day by day, I'm getting better taste, but I no longer have any genius." He also said, "My old head's imagination is worn out. It's not smart at this age to practice arts that are only about imagination."

Rameau composed a lot in the late 1740s and early 1750s. After that, he wrote less. This was probably due to his age and health. But he still wrote another comic opera, Les Paladins, in 1760. His last tragédie en musique, Les Boréades, was supposed to follow. But for unknown reasons, it was never performed. It had to wait until the late 1900s for a proper staging.

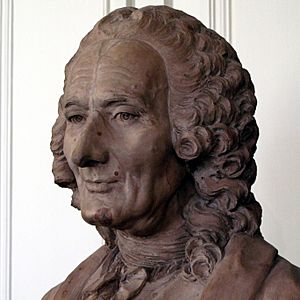

Rameau died on September 12, 1764, after a fever. This was thirteen days before his 81st birthday. He was buried in the church of St. Eustache, Paris, on the same day. A bronze bust and tombstone were put up in his memory in 1883. However, the exact spot where he was buried is still unknown.

Rameau's Personality

We do not know much about Rameau's personal and family life. His music is graceful and charming. But it does not match how he was seen in public. Diderot described him in his book Le Neveu de Rameau. Music was Rameau's main passion. It filled his thoughts. Philippe Beaussant called him a "monomaniac." Piron said, "His heart and soul were in his harpsichord; once he had shut its lid, there was no one home."

Rameau was tall and very thin. You can see this in his portraits. He had a "loud voice." His speech was hard to understand, like his handwriting. As a person, he was secretive and liked to be alone. He was often irritable. He was proud of his achievements, especially as a theorist. He was quick to get angry with those who disagreed with him. It is hard to imagine him among the clever people at La Poupelinière's salon. His music was his way in, making up for his lack of social skills.

His enemies made his faults seem worse. For example, they said he was very stingy. But his careful spending was likely from years of not having much money. He could also be generous. He helped his nephew Jean-François when he came to Paris. He also helped Claude-Bénigne Balbastre start his career. He gave his daughter Marie-Louise a large gift when she became a nun in 1750. He also paid money to one of his sick sisters.

He only became financially secure later in life. This was after his operas became successful. He also received a royal pension. A few months before he died, he was made a knight. But he did not change his lifestyle. He kept his old clothes, one pair of shoes, and old furniture. After he died, people found he only had one old harpsichord in his rooms. But he also had a bag with 1691 gold coins.

Rameau's Music

What Rameau's Music Sounds Like

Rameau's music shows his amazing technical knowledge. He wanted to be known as a music theorist. But his music is not just for smart people. Rameau himself said, "I try to hide art with art." His music was new and used techniques never heard before. Yet, it still used old forms.

To the Lullyistes, Rameau seemed revolutionary. They were bothered by his complex harmonies. To the philosophes (thinkers), he seemed old-fashioned. They only cared about the meaning of his music. They did not or could not listen to the sound it made. People did not always understand Rameau's daring experiments. For example, he had to remove a part from Hippolyte et Aricie. This was because the singers could not or would not perform it correctly.

Types of Music Rameau Wrote

Rameau's music can be put into four main groups. They are very different in importance.

- A few cantatas (pieces for singers and instruments).

- Some motets (church music for choir).

- Pieces for solo harpsichord or harpsichord with other instruments.

- His works for the stage (operas and ballets). He spent the last 30 years of his career almost only on these.

Like many composers of his time, Rameau often reused melodies that were popular. But he always changed them carefully. He did not just copy them. He did not borrow music from other composers. However, his earliest works show the influence of other music. Rameau often reworked his own material. For example, in Les Fêtes d'Hébé, he used pieces from his 1724 harpsichord book. He also used a song from the cantata Le Berger Fidèle.

Motets

Rameau was a church organist for at least 26 years. Yet, he wrote very little church music. He also wrote no organ music. It seems it was not his favorite type of music. It was just a way to earn money. Still, Rameau's few religious pieces are very good. Only four motets are definitely by Rameau: Deus noster refugium, In convertendo, Quam dilecta, and Laboravi.

Cantatas

The cantata was a very popular type of music in the early 1700s. The French cantata was "invented" in 1706. Many famous composers used this style. Cantatas were Rameau's first try at dramatic music. Cantatas needed only a few musicians. This made them easy for a composer who was not yet famous. Music experts can only guess when Rameau's six surviving cantatas were written. We also do not know who wrote the words for them.

Instrumental Music

Rameau, along with François Couperin, was a master of French harpsichord music. Both broke away from earlier styles. Rameau and Couperin had different styles. It seems they did not know each other. Couperin was an official court musician. Rameau, 15 years younger, became famous only after Couperin died.

Rameau published his first harpsichord book in 1706. (Couperin waited until 1713). Rameau's music includes pieces in the French style. Some imitate sounds, like "Le rappel des oiseaux" (The birds' call) and "La poule" (The hen). Others show character, like "Les tendres plaintes" (Tender laments). But there are also very difficult pieces, like "Les tourbillons" (The whirlwinds). Some pieces show his experiments as a theorist, like "L'enharmonique." These influenced other composers. Rameau's harpsichord suites are grouped by musical key.

Rameau's second and third harpsichord collections came out in 1724 and 1727. After these, he wrote only one more harpsichord piece. This was "La Dauphine" (1747). The short "Les petits marteaux" (around 1750) is also thought to be his.

During a quiet period (1740 to 1744), he wrote the Pièces de clavecin en concerts (1741). Some experts think these are the best French Baroque chamber music pieces. In these, the harpsichord is not just for background music. It plays an equal part with other instruments like the violin and flute. Rameau said this music would sound good on the harpsichord alone. But he still wrote out five of them for harpsichord only.

Opera

After 1733, Rameau mostly focused on opera. French Baroque opera in the 1700s was richer than Italian opera. It had more choruses and dances. The music also flowed better between the arias (songs) and recitatives (spoken-like parts). Italian opera of Rameau's time had clear breaks between songs and spoken parts. The action happened during the spoken parts. The songs were mostly to show off the singer's skill.

French opera was different. Since Lully, the words had to be clear. This limited techniques like vocalizing (singing many notes on one syllable). A good balance existed between the more musical and less musical parts. This continuous music style was like what Wagner would do much later.

Rameau's operas have five main parts:

- Pure Music: These are pieces like overtures (introductions) and music that ends scenes. Rameau's overtures were very varied. Even his early ones were new and unique. Some are striking, like the overture to Zaïs, which shows chaos before creation.

- Dance Music: Dances were a must in operas. Rameau used them to show his amazing sense of rhythm and melody. He wrote many gavottes, minuets, and other dance forms.

- Choruses: Rameau was a master of harmony. He wrote grand choruses for different feelings. They could be for one voice, many voices, or with the orchestra.

- Arias: These were less common than in Italian opera. But Rameau wrote many striking ones. Famous examples include "Tristes apprêts" from Castor et Pollux.

- Recitative: This was closer to singing than speaking. Rameau carefully matched the music to the French words. He used his harmony skills to show the characters' feelings.

In the first part of his opera career (1733–1739), Rameau wrote his great works. These included three tragédies en musique and two opéra-ballets. These are still central to his music today. After his break from 1740 to 1744, he became the official court musician. He mostly wrote pieces for entertainment. These had lots of dance music. In his last years, Rameau returned to a new version of his early style. This can be heard in Les Paladins and Les Boréades.

His opera Zoroastre was first performed in 1749. One of Rameau's fans, Cuthbert Girdlestone, said this opera is special among his works.

Rameau and His Librettists

Unlike Lully, who worked with one writer for most of his operas, Rameau rarely worked with the same librettist (the person who writes the words for an opera) twice. He was very demanding and had a bad temper. He could not keep long-term partnerships with his librettists. The only exception was Louis de Cahusac. He worked with Rameau on several operas.

Many Rameau experts wish he had worked with Houdar de la Motte. They also regret that the Samson project with Voltaire did not happen. This is because the librettists Rameau did work with were not top-notch. He met most of them at places where important cultural figures gathered.

None of his librettists wrote words as good as Rameau's music. The plots were often too complex or unbelievable. But this was common for operas at the time. The poetry was also often not great. Rameau often had to change the words and rewrite music after the first performance. This is why we have different versions of Castor et Pollux (1737 and 1754) and Dardanus (1739, 1744, and 1760).

Rameau's Fame and Influence

By the end of his life, Rameau's music was criticized in France. People there preferred Italian music. However, foreign composers who liked Italian music started to look at Rameau. They saw his work as a way to improve their own opera style.

Tommaso Traetta wrote two operas based on Rameau's librettos. These showed Rameau's influence. Christoph Willibald Gluck was a very important "reformist" composer. His three Italian operas from the 1760s show he knew Rameau's works. For example, both Gluck's Orfeo and Rameau's 1737 Castor et Pollux start with a main character's funeral. That character later comes back to life. Many of the opera changes Gluck suggested were already in Rameau's works.

When Gluck came to Paris in 1774, he was seen as continuing Rameau's tradition. However, Gluck's popularity lasted, but Rameau's did not. By the end of the 1700s, Rameau's operas were no longer performed.

For most of the 1800s, Rameau's music was not played. It was only known by its reputation. Hector Berlioz studied Castor et Pollux and liked the song "Tristes apprêts." But he felt a big difference between his music and Rameau's.

After France lost the Franco-Prussian War in 1870–71, Rameau's music gained new interest. People wanted to celebrate French heroes. In 1894, composer Vincent d'Indy started the Schola Cantorum. This group promoted French music. They performed several of Rameau's works again. Claude Debussy was in the audience. He especially loved Castor et Pollux, which was revived in 1903. Debussy said that Gluck's genius was rooted in Rameau's works.

Camille Saint-Saëns and Paul Dukas also helped bring Rameau's music to attention. But interest in Rameau faded again. It was not until the late 1900s that serious efforts were made to revive his works. Now, more than half of Rameau's operas have been recorded. Conductors like John Eliot Gardiner and William Christie have recorded them.

One of Rameau's pieces is often heard in the Victoria Centre in Nottingham, England. It plays on the Rowland Emett clock, the Aqua Horological Tintinnabulator. Emett said that Rameau made music for his school and the shopping center without knowing it.

Rameau's Books on Music Theory

The Treatise on Harmony (1722)

Rameau's 1722 book, Treatise on Harmony, changed music theory forever. Rameau said he found the "fundamental law" of all Western music. He called it the "fundamental bass." He was greatly influenced by new ways of thinking and analyzing. Rameau used math, comments, and teaching methods. He wanted to explain the structure of music scientifically.

He used careful logic to find universal harmony rules from natural causes. Earlier books on harmony were only about how to play music. Rameau used the new scientific thinking. He quickly became famous in France as the "Isaac Newton of Music." His fame spread across Europe. His Treatise became the main book on music theory. It is still the basis for teaching Western music today.

List of Rameau's Works

RCT numbers are from the Rameau Catalogue Thématique.

Instrumental Works

- Pièces de clavecin. Three books. Pieces for harpsichord, published 1706, 1724, 1726/27(?)

- RCT 1 – Premier livre de Clavecin (1706)

- RCT 2 – Pièces de clavecin (1724) – Suite in E minor

- RCT 3 – Pièces de clavecin (1724) – Suite in D major

- RCT 4 – Pièces de clavecin (1724) – Menuet in C major

- RCT 5 – Nouvelles suites de pièces de clavecin (1726/27) – Suite in A minor

- RCT 6 – Nouvelles suites de pièces de clavecin (1726/27) – Suite in G

- Pieces de clavecin en concerts Five albums of character pieces for harpsichord, violin and viol. (1741)

- RCT 7 – Concert I in C minor

- RCT 8 – Concert II in G major

- RCT 9 – Concert III in A major

- RCT 10 – Concert IV in B-flat major

- RCT 11 – Concert V in D minor

- RCT 12 – La Dauphine for harpsichord. (1747)

- RCT 12bis – Les petits marteaux for harpsichord.

- Several orchestral dance suites taken from his operas.

Motets

- RCT 13 – Deus noster refugium (c. 1713–1715)

- RCT 14 – In convertendo (probably before 1720, revised 1751)

- RCT 15 – Quam dilecta (c. 1713–1715)

- RCT 16 – Laboravi (published in the Traité de l'harmonie, 1722)

Canons

- RCT 17 – Ah! loin de rire, pleurons (soprano, alto, tenor, bass) (published 1722)

- RCT 18 – Avec du vin, endormons-nous (2 sopranos, Tenor) (1719)

- RCT 18bis – L'épouse entre deux draps (3 sopranos) (once thought to be by François Couperin)

- RCT 18ter – Je suis un fou Madame (3 equal voices) (1720)

- RCT 19 – Mes chers amis, quittez vos rouges bords (3 sopranos, 3 basses) (published 1780)

- RCT 20 – Réveillez-vous, dormeur sans fin (5 equal voices) (published 1722)

- RCT 20bis – Si tu ne prends garde à toi (2 sopranos, bass) (1720)

Songs

- RCT 21.1 – L'amante préoccupée or A l'objet que j'adore (soprano, continuo) (1763)

- RCT 21.2 – Lucas, pour se gausser de nous (soprano, bass, continuo) (published 1707)

- RCT 21.3 – Non, non, le dieu qui sait aimer (soprano, continuo) (1763)

- RCT 21.4 – Un Bourbon ouvre sa carrière or Un héros ouvre sa carrière (alto, continuo) (1751, song from Acante et Céphise but removed before first performance)

Cantatas

- RCT 23 – Aquilon et Orithie (between 1715 and 1720)

- RCT 28 – Thétis (same period)

- RCT 26 – L'impatience (same period)

- RCT 22 – Les amants trahis (around 1720)

- RCT 27 – Orphée (same period)

- RCT 24 – Le berger fidèle (1728)

- RCT 25 – Cantate pour le jour de la Saint Louis (1740)

Operas and Stage Works

Tragédies en musique

- RCT 43 – Hippolyte et Aricie (1733; revised 1742 and 1757)

- RCT 32 – Castor et Pollux (1737; revised 1754)

- RCT 35 – Dardanus (1739; revised 1744 and 1760)

- RCT 62 – Zoroastre (1749; revised 1756, with new music for Acts II, III & V)

- RCT 31 – Les Boréades or Abaris (never performed; in rehearsal 1763)

Opéra-ballets

- RCT 44 – Les Indes galantes (1735; revised 1736)

- RCT 41 – Les fêtes d'Hébé or les Talens Lyriques (1739)

- RCT 39 – Les fêtes de Polymnie (1745)

- RCT 59 – Le temple de la gloire (1745; revised 1746)

- RCT 38 – Les fêtes de l'Hymen et de l'Amour or Les Dieux d'Egypte (1747)

- RCT 58 – Les surprises de l'Amour (1748; revised 1757)

Pastorales héroïques

- RCT 60 – Zaïs (1748)

- RCT 49 – Naïs (1749)

- RCT 29 – Acante et Céphise or La sympathie (1751)

- RCT 34 – Daphnis et Eglé (1753)

Comédies lyriques

- RCT 53 – Platée or Junon jalouse (1745)

- RCT 51 – Les Paladins or Le Vénitien (1760)

Comédie-ballet

- RCT 54 – La princesse de Navarre (1744)

Actes de ballet

- RCT 33 – Les courses de Tempé (1734)

- RCT 40 – Les fêtes de Ramire (1745)

- RCT 52 – Pigmalion (1748)

- RCT 42 – La guirlande or Les fleurs enchantées (1751)

- RCT 57 – Les sibarites or Sibaris (1753)

- RCT 48 – La naissance d'Osiris or La Fête Pamilie (1754)

- RCT 30 – Anacréon (1754)

- RCT 58 – Anacréon (completely different work from the above, 1757, 3rd part of Les surprises de l'Amour)

- RCT 61 – Zéphire (date unknown)

- RCT 50 – Nélée et Myrthis (date unknown)

- RCT 45 – Io (unfinished, date unknown)

Lost Works

- RCT 56 – Samson (tragédie en musique) (first version 1733–1734; second version 1736; never performed)

- RCT 46 – Linus (tragédie en musique) (1751, music stolen after a rehearsal)

- RCT 47 – Lisis et Délie (pastorale) (planned for November 6, 1753)

Incidental Music for Opéras Comiques

Most of this music is lost.

- RCT 36 – L'endriague (in 3 acts, 1723)

- RCT 37 – L'enrôlement d'Arlequin (in 1 act, 1726)

- RCT 55 – La robe de dissension or Le faux prodige (in 2 acts, 1726)

- RCT 55bis – La rose or Les jardins de l'Hymen (in a prologue and 1 act, 1744)

Writings

- Traité de l'harmonie réduite à ses principes naturels (Paris, 1722)

- Nouveau système de musique théorique (Paris, 1726)

- Dissertation sur les différents méthodes d'accompagnement pour le clavecin, ou pour l'orgue (Paris, 1732)

- Génération harmonique, ou Traité de musique théorique et pratique (Paris, 1737)

- Mémoire où l'on expose les fondemens du Système de musique théorique et pratique de M. Rameau (1749)

- Démonstration du principe de l'harmonie (Paris, 1750)

- Nouvelles réflexions de M. Rameau sur sa 'Démonstration du principe de l'harmonie' (Paris, 1752)

- Observations sur notre instinct pour la musique (Paris, 1754)

- Erreurs sur la musique dans l'Encyclopédie (Paris, 1755)

- Suite des erreurs sur la musique dans l'Encyclopédie (Paris, 1756)

- Reponse de M. Rameau à MM. les editeurs de l'Encyclopédie sur leur dernier Avertissement (Paris, 1757)

- Nouvelles réflexions sur le principe sonore (1758–59)

- Code de musique pratique, ou Méthodes pour apprendre la musique...avec des nouvelles réflexions sur le principe sonore (Paris, 1760)

- Lettre à M. Alembert sur ses opinions en musique (Paris, 1760)

- Origine des sciences, suivie d'un controverse sur le même sujet (Paris, 1762)

See also

In Spanish: Jean-Philippe Rameau para niños

In Spanish: Jean-Philippe Rameau para niños