Rebecca Clarke (composer) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Rebecca Clarke

|

|

|---|---|

Rebecca Clarke in the yard at Gayton Corner, Harrow, with violin, c. 1908.

|

|

| Born | Rebecca Helferich Clarke August 27, 1886 Harrow, London, England |

| Died | October 13, 1979 (aged 93) New York City, U.S. |

| Occupation |

|

| Education | Royal College of Music |

| Notable works | Viola Sonata (1919); The Tiger for voice and piano (1929–1933); words by William Blake |

| Spouse | James Friskin |

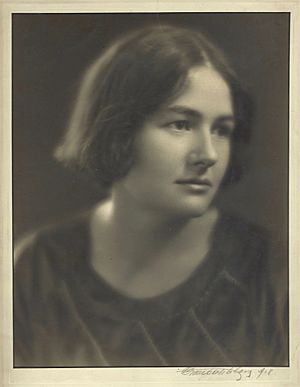

Rebecca Helferich Clarke (born August 27, 1886 – died October 13, 1979) was a talented British-American classical composer and violist. She was known around the world as an amazing viola player. She also became one of the first women to play professionally in an orchestra. Rebecca Clarke was born in England to a German mother and an American father. She held both British and American citizenship. She spent much of her life in the United States, settling there permanently after World War II.

Clarke studied music at the Royal Academy of Music and the Royal College of Music in London. She was visiting the United States when World War II began and could not return home. In 1944, she married composer and pianist James Friskin. Rebecca Clarke passed away at her home in New York when she was 93 years old. Even though she didn't write a huge amount of music, her work was admired for its skill and artistic power. Many of her pieces were published only recently, and interest in her music grew again in 1976.

Contents

Early Life and Music Studies

Rebecca Clarke was born in Harrow, England. Her father, Joseph Thacher Clarke, was American, and her mother, Agnes Paulina Marie Amalie Helferich, was German. Her father loved music, and Rebecca started playing the violin after listening to her younger brother's lessons.

She began her studies at the Royal Academy of Music in 1903. However, her father made her leave in 1905. Later, her harmony teacher, Percy Hilder Miles, left her his valuable Stradivarius violin in his will. Soon after leaving the Royal Academy, she made her first trip to the United States. She then attended the Royal College of Music. There, she became one of Sir Charles Villiers Stanford's first female students for music composition.

Becoming a Violist

Sir Stanford encouraged Rebecca to switch from the violin to the viola. At that time, the viola was just starting to be seen as a solo instrument. She studied with Lionel Tertis, who many considered the best violist of his time. In 1910, she wrote a song called "Tears" based on Chinese poetry. She worked on this with other students at the Royal College of Music. She also sang in a student group led by Ralph Vaughan Williams. This group studied and performed music by Palestrina.

Rebecca's father stopped supporting her financially after she criticized his personal life. Because of this, she had to leave the Royal College in 1910. She supported herself by playing the viola. In 1912, Sir Henry Wood chose her to play in the Queen's Hall Orchestra. This made her one of the first professional female orchestra musicians. In 1916, she moved to the United States to continue her performing career.

A Hidden Talent Revealed

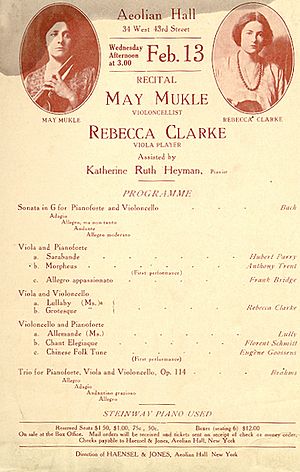

In 1918, Rebecca Clarke performed a short, beautiful piece for viola and piano called Morpheus. She used the pseudonym (a fake name) "Anthony Trent" for this piece. It was played for the first time at a concert in New York City with cellist May Mukle. Critics praised the "Trent" piece but didn't pay much attention to the other works she performed under her own name. A year later, she announced that Morpheus was her own work and never used a fake name again.

Her most successful period as a composer began with her viola sonata. She entered this piece in a competition in 1919. The competition was sponsored by Elizabeth Sprague Coolidge, who was Clarke's neighbor and a supporter of the arts.

The competition was judged anonymously, meaning the judges didn't know who wrote each piece. There were 72 entries. The judges especially liked two pieces: a suite by Ernest Bloch and Clarke's Sonata. They couldn't decide which was better. The final decision went to Bloch's Suite. However, the judges were so impressed by Clarke's work that they broke a rule and revealed the author's name. They were surprised to learn that such an excellent piece was written by a woman.

The sonata was very well received and was first performed at the Berkshire music festival in 1919. In 1921, Clarke again did well in Coolidge's competition with her piano trio, though she didn't win the top prize. In 1923, she wrote a rhapsody for cello and piano, also sponsored by Coolidge. This made Clarke the only female artist to receive Coolidge's support multiple times. These three works show the peak of Clarke's career as a composer.

Later Life and Marriage

In 1924, after a world tour in 1922–23, Clarke started a career as a solo and group performer in London. In 1927, she helped create the English Ensemble, a piano quartet. This group included herself, Marjorie Hayward, Kathleen Long, and May Mukle. She also made several recordings in the 1920s and 1930s and performed on BBC radio. During this time, she composed much less music. However, she continued to perform, including at the Paris Colonial Exhibition in 1931 with the English Ensemble.

When World War II started, Clarke was visiting her two brothers in the US. She couldn't get a visa to return to Britain. She lived with her brothers' families for a while. In 1942, she became a governess for a family in Connecticut. She composed 10 works between 1939 and 1942, including her Passacaglia on an Old English Tune.

Rebecca had first met James Friskin, a composer, concert pianist, and a founder of the Juilliard School, when they were both students at the Royal College of Music. They reconnected by chance on a street in Manhattan in 1944. They married in September of that year, both in their late 50s.

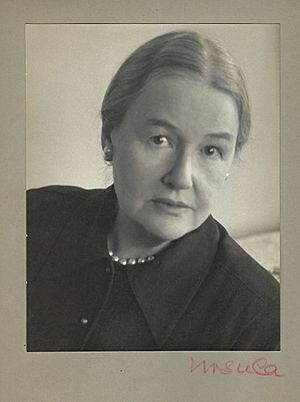

Music expert Stephen Banfield has called Clarke the most important British female composer of her time. However, after her marriage, she composed less often. She stopped composing entirely, even though her husband encouraged her. She continued to work on music arrangements until shortly before her death. She also stopped performing.

Clarke sold the Stradivarius violin she had received. She used the money to create the May Mukle prize at the Royal Academy. This prize is still given every year to an outstanding cellist.

Later Years and Passing

After her husband died in 1967, Rebecca Clarke began writing a memoir (a personal story) called I Had a Father Too (or the Mustard Spoon). She finished it in 1973, but it was never published. In this book, she wrote about her early life. She described how her father often hit her and how difficult her family relationships were. These experiences affected how she saw her place in the world. Rebecca Clarke died in 1979 at her home in New York City at the age of 93. She was cremated.

Rebecca Clarke's Music

A large part of Rebecca Clarke's music features the viola. This is because she was a professional violist for many years. Much of her music was written for herself and the all-female music groups she played in. These groups included the Norah Clench Quartet, the English Ensemble, and the d'Aranyi Sisters. She also toured worldwide, especially with cellist May Mukle. Her works were greatly influenced by different styles in 20th-century classical music. Clarke also knew many important composers of her time, like Bloch and Ravel. Her work has been compared to theirs.

Key Compositions

The Viola Sonata is still a standard piece played by violists today. It was published in the same year as viola sonatas by Bloch and Hindemith. Morpheus, written a year earlier, was her first big work after many years of writing songs and short pieces. The Rhapsody that Elizabeth Coolidge sponsored is Clarke's most ambitious work. It is about 23 minutes long and has complex musical ideas. Its changing moods come from its unclear musical keys. In contrast, "Midsummer Moon," written the next year, is a light, short piece with a flowing solo violin part.

Besides her chamber music for strings, Clarke wrote many songs. Nearly all of her early pieces are for a solo singer and piano. Her 1933 song "Tiger, Tiger," based on Blake's poem "The Tyger", is dark and intense. She worked on it for five years and revised it in 1972. Most of her other songs, however, are lighter. Her earliest works were simple "parlour songs." She later wrote many songs using classic poems by Yeats, Masefield, and A.E. Housman.

Later Musical Style

From 1939 to 1942, Clarke had her last very productive period as a composer. During this time, her style became clearer and more focused on counterpoint (two or more melodies played at the same time). She emphasized musical ideas that repeat and clear musical structures. These are features of neoclassicism, a style that looked back to earlier classical music.

Dumka (1941), a recently published work for violin, viola, and piano, sounds like Eastern European folk music. It reminds listeners of composers like Bartók and Martinů. The "Passacaglia on an Old English Tune," also from 1941, was first played by Clarke herself. It is based on a tune by Thomas Tallis that appears throughout the piece. The music has a Dorian mode feel, which is a type of musical scale. The piece is dedicated to "BB," possibly her niece Magdalen. Some experts think it might refer to Benjamin Britten, who organized a concert for Clarke's friend Frank Bridge. The Prelude, Allegro, and Pastorale, also from 1941, is another neoclassically influenced piece. It was written for clarinet and viola, originally for her brother and sister-in-law.

Rebecca Clarke did not compose any large works like symphonies. Her total compositions include 52 songs, 11 choral works, 21 chamber pieces, the Piano Trio, and the Viola Sonata. Her music was mostly forgotten for a long time. However, interest in her work grew again in 1976 after a radio show celebrated her 90th birthday. More than half of Clarke's compositions are still not published. They are kept by her family, along with most of her writings. But in the early 2000s, more of her works were printed and recorded. For example, two string quartets and Morpheus were published in 2002.

Today, people generally have a positive view of Clarke's music. A review of her Viola Sonata in 1981 called it a "thoughtful, well constructed piece" from a composer who was not well known. A 1985 review noted its "emotional intensity and use of dark tone colours." Andrew Achenbach, reviewing a recording of Clarke's works, called Morpheus "striking" and "languorous." Laurence Vittes said Clarke's "Lullaby" was "exceedingly sweet and tender." A 1987 review concluded that "it seems astonishing that such splendidly written and deeply moving music should have lain in obscurity all these years."

On October 17, 2015, BBC Radio 3's Building a Library show featured her Viola Sonata. The top recommendation was by Tabea Zimmermann (viola) and Kirill Gerstein (piano). In 2017, BBC Radio 3 dedicated five hours to her music as Composer of the Week.

Selected Works

For a complete listing, see List of compositions by Rebecca Clarke.

- Chamber music

- 2 Pieces: Lullaby and Grotesque for viola (or violin) and cello (c. 1916)

- Morpheus for viola and piano (1917–1918)

- Sonata for viola and piano (1919)

- Piano Trio (1921)

- Rhapsody for cello and piano (1923)

- Passacaglia on an Old English Tune for viola (or cello) and piano (?1940–1941)

- Prelude, Allegro and Pastorale for viola and clarinet (1941)

- Vocal

- Shiv and the Grasshopper for voice and piano (1904); words from The Jungle Book by Rudyard Kipling

- Shy One for voice and piano (1912); words by William Butler Yeats

- He That Dwelleth in the Secret Place (Psalm 91) for soloists and mixed chorus (1921)

- The Seal Man for voice and piano (1922); words by John Masefield

- The Aspidistra for voice and piano (1929); words by Claude Flight

- The Tiger for voice and piano (1929–1933); words by William Blake

- God Made a Tree for voice and piano (1954); words by Katherine Kendall

- Choral

- Music, When Soft Voices Die for mixed chorus (1907); words by Percy Bysshe Shelley

|

Article contributor: Chris Johnson;

|

See also

In Spanish: Rebecca Clarke para niños

In Spanish: Rebecca Clarke para niños