Richard Crashaw facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Richard Crashaw

|

|

|---|---|

| Born | c. 1612–1613 London, England |

| Died | 21 August 1649 (aged 36) Loreto, March of Ancona, Papal States |

| Occupation | poet, teacher |

| Alma mater | Charterhouse School, Pembroke College, Cambridge |

| Literary movement | Metaphysical poets |

| Notable works | Epigrammaticum Sacrorum Liber (1634) Steps to the Temple (1646) Delights of the Muses (1648) Carmen Deo Nostro (1652) |

Richard Crashaw (around 1613 – August 21, 1649) was an English poet and teacher. He was also a clergyman who later became a Roman Catholic. He is known as one of the important metaphysical poets of the 1600s.

Crashaw was the son of a well-known Anglican preacher. His father had strong Puritan beliefs and often wrote against Catholicism. After his father passed away, Richard went to Charterhouse School and then Pembroke College, Cambridge.

After college, Crashaw taught at Peterhouse, Cambridge. He started publishing religious poems. These poems showed his deep mystical side and strong Christian faith.

Crashaw became a priest in the Church of England. He followed the "High Church" ideas of William Laud, who was the Archbishop of Canterbury. Puritans did not like Crashaw because he used Christian art to decorate his church. He also showed great devotion to the Virgin Mary and used Catholic-style clothing for services.

During these years, the University of Cambridge supported High Church Anglicanism. It also supported the Royalists, who were loyal to King Charles I. Both groups faced harsh treatment from Puritan forces during the English Civil War (1642–1651).

In 1643, Puritan General Oliver Cromwell took control of Cambridge. Crashaw lost his job and became a refugee. He first went to France, then to the Papal States (parts of Italy ruled by the Pope). He found work helping Cardinal Giovanni Battista Maria Pallotta in Rome. While in exile, he changed his religion from Anglicanism to Roman Catholicism. In 1649, Cardinal Pallotta gave Crashaw a small church position in Loreto, Italy. Crashaw died there suddenly four months later.

Crashaw's poetry is often grouped with other English metaphysical poets. However, it also shares similarities with Baroque poets. His work was partly influenced by Italian and Spanish mystical writers. His poems often connect the beauty of nature with the deeper meaning of life. They also focus on "love with the smaller graces of life and the profounder truths of religion."

| Top - 0-9 A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z |

Richard Crashaw's Life Story

Early Years

His Parents

Richard Crashaw was born in London, England, around 1612 or 1613. He was the only son of William Crashaw (1572–1626). We don't know the exact date of Richard's birth or his mother's name. It's thought he was born in late 1612 or early 1613. His mother, William Crashaw's first wife, might have died when he was a baby. William Crashaw's second wife died in 1620.

William Crashaw was a clergyman who studied at Cambridge. He was a preacher in London. He came from a wealthy family in Yorkshire. William Crashaw wrote many pamphlets that supported Puritan ideas. These writings were very critical of Catholicism. Even so, William Crashaw liked some Catholic devotions. He translated many poems by Catholic writers from Latin into English.

His Childhood

Experts believe that Richard Crashaw read many books from his father's large library. This library had many Catholic works. It was called "one of the finest private theological libraries of the time."

When William Crashaw died in 1626, Richard became an orphan. He was about 13 or 14 years old. Two important legal figures, Sir Henry Yelverton and Sir Ranulph Crewe, became his guardians.

His Education

Charterhouse School

Crashaw's guardians sent him to the Charterhouse School in 1629. The headmaster, Robert Brooke, made students write poems in Greek and Latin. These poems were based on Bible readings from chapel services. Crashaw continued this practice at Cambridge.

Years later, he put many of these poems together. This became his first book of poems, Epigrammatum Sacrorum Liber. This means "A Book of Sacred Epigrams." It was published in 1634. After Charterhouse, Crashaw went to Pembroke Hall at Cambridge University.

Pembroke Hall

Before he graduated from Pembroke Hall in 1634, Crashaw was likely very Protestant. This was probably just as his father would have wanted. But during his studies, Crashaw became interested in the "High Church" tradition. This part of Anglicanism focused on the church's Catholic history and rituals.

These ideas were supported by William Laud, the Archbishop of Canterbury. King Charles I also supported Laud. They wanted to bring "beauty in holiness" to the Church of England. This meant more respect and order in church services. It also meant more decoration in churches and more detailed rituals. This movement was called Laudianism. It was influenced by the Counter-Reformation, which was the Catholic Church's response to the Protestant Reformation. Cambridge University was a center for Laudianism when Crashaw was there.

Richard Crashaw started at Pembroke on March 26, 1632. The college master was Reverend Benjamin Lany. Lany was an Anglican clergyman and a friend of William Crashaw. Lany had once shared William Crashaw's Puritan beliefs. But his views changed towards High Church practices. Richard Crashaw was likely influenced by Lany at Pembroke.

Crashaw also knew Nicholas Ferrar. He visited Ferrar's Little Gidding community. This was a family religious group known for its High Church rituals. They lived a humble life of prayer, avoiding worldly things. Puritans criticized Little Gidding, calling it a "Protestant Nunnery."

Pembroke Hall gave Crashaw a Bachelor of Arts degree in 1634. He received a Master of Arts from Cambridge in 1638. He also received the same degree from the University of Oxford in 1641.

Church Life and Cambridge

Curate in Cambridge

In 1636, Crashaw became a Fellow at Peterhouse, Cambridge. In 1638, he became a priest in the Church of England. He then became the curate (assistant priest) at the Church of St Mary the Less in Cambridge. This church, often called "Little St Mary's," is next to Peterhouse. It was the college chapel until 1632.

The Master of Peterhouse, John Cosin, and many Fellows supported Laudianism. They embraced the Anglican Church's Catholic heritage. Crashaw became close to the Ferrar family and often visited Little Gidding. Crashaw brought these influences into his work at St Mary the Less. He held late-night prayer vigils. He also decorated the chapel with holy objects, crucifixes, and images of Mary, mother of Jesus.

An early writer about Crashaw, David Lloyd, said Crashaw's sermons attracted many people. They were "more like Poems" and filled listeners with joy.

Because of the conflict between Laudian supporters and Puritans, spies often attended church services. They looked for "superstitious" or "Popish" (Catholic-like) practices. In 1641, Crashaw was criticized for showing too much devotion to the Virgin Mary. He was also criticized for "diverse bowings" and using incense before the altar.

English Revolution

In 1643, Cromwell's forces took over Cambridge. They immediately started to stop Catholic influences. Crashaw had to leave his position at Peterhouse. He refused to sign the Solemn League and Covenant, a document supporting Parliament. He soon decided to leave England. He was joined by Mary Collet, whom he respected deeply. He arranged for Mary's son, Collete Ferrer, to take his place at Peterhouse.

Soon after Crashaw left Cambridge, St Mary's church was damaged. This happened on December 29 and 30, 1643. William Dowsing led this under orders from Parliament. Dowsing wrote that at Little St Mary's, "we brake downe 60 superstitious pictures, some popes, and crucifixes."

Crashaw's poetry began to use strong Catholic images. This was especially true in his poems about the Spanish mystic St Teresa of Avila. Teresa's writings were not known in England and were not available in English. But Crashaw had learned about her work. His three poems honoring her—"A Hymn to Sainte Teresa," "An Apologie for the fore-going Hymne," and "The Flaming Heart"—are considered some of his best works.

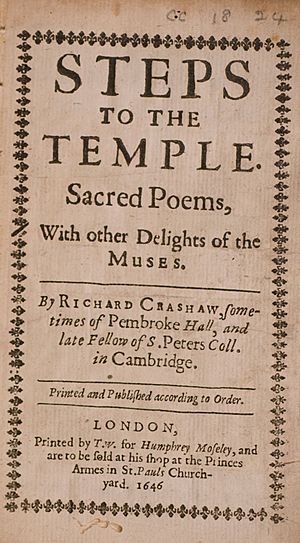

Crashaw also started writing poems influenced by George Herbert's collection The Temple. This influence likely came from Herbert's connection to Nicholas Ferrar. Crashaw later put some of these poems into a collection. It was called Steps to the Temple and The Delights of the Muses. An unknown friend published it in one book in 1646. This collection included Crashaw's translation of Giambattista Marini's Sospetto d'Herode. The editor said the poems could "lift thee Reader, some yards above the ground."

Exile, Conversion, and Death

Becoming Catholic

In 1644, Crashaw and Mary Collet settled in Leiden, Netherlands. It is believed he became a Catholic at this time. According to an old book from 1692, Crashaw converted because he feared the Puritans would destroy his beloved Anglican Church.

Around 1645, Crashaw was in Paris. There he met Reverend Thomas Car, who helped English refugees. The poet's difficult life left a strong impression on Car.

His Last Years

The writer Abraham Cowley found Crashaw living in great poverty in Paris. Cowley asked the English Queen Henrietta Maria, who was also in exile in France, for help. He wanted her to help Crashaw get a job in Rome. Crashaw's friend and supporter, Susan Feilding, Countess of Denbigh, also asked the Queen to recommend Crashaw to Pope Innocent X.

Crashaw traveled to Rome in November 1646. He lived there in poor health and poverty while waiting for a position from the Pope. Crashaw was finally introduced to Innocent X. He was called "the learned son of a famous Heretic." After the Queen's repeated requests, Innocent X finally gave Crashaw a job in 1647. He worked for Cardinal Giovanni Battista Maria Pallotta. Pallotta was connected to the English College, Rome, a school for priests in Rome. Crashaw was allowed to live at the college.

At the college, Crashaw saw some problems among Pallotta's staff. He reported these to the Cardinal. This made Crashaw many enemies. So, Pallotta eventually moved him from the college for his safety. In April 1649, Pallotta found a church position for Crashaw. It was at the Basilica della Santa Casa in Loreto, Marche. Crashaw left for Loreto in May 1649.

Crashaw had been weakened by years of hardship. He died in Loreto from a fever on August 21, 1649. Some people suspected he might have been poisoned by his enemies. Crashaw was buried in the lady chapel of the shrine in Loreto.

Crashaw's Poetry

How His Poems Were Written and Published

Three collections of Crashaw's poems were published while he was alive. One small book was published after he died, three years later. This last collection, Carmen Deo Nostro, included 33 poems.

For his first book of poems, Crashaw used the short poems he wrote in school. He put these together to create Epigrammatum Sacrorum Liber (meaning "A Book of Sacred Epigrams"). It was published in 1634. One famous line from this book is about the miracle of Jesus turning water into wine (John 2:1–11). It says: Nympha pudica Deum vidit, et erubuit. This is often translated as "the modest water saw its God, and blushed."

For example, this four-line poem, called Dominus apud suos vilis, came from a passage in the Gospel of Luke:

|

Crashaw's poem (1634)

|

A simple translation

|

Main Ideas in His Poetry

Crashaw's poems mainly focus on seeking divine love. According to one historian, his poems show "new springs of tenderness." This happened as he became interested in a loving view of God. He also liked the charity practiced by his college master, Benjamin Laney. He also studied the Virgin Mary and the Christ Child deeply in his poetry.

He often shows women, especially the Virgin Mary, but also Teresa and Mary Magdalene, as examples of goodness, purity, and salvation. His three poems honoring Saint Teresa of Avila are considered his most beautiful works.

While Crashaw is called a metaphysical poet, his poetry is different. It shows influences from many European countries. One writer, Lorraine M. Roberts, says Crashaw "happily set out to follow in the steps of George Herbert." This refers to Herbert's book The Temple (1633). Crashaw's poems show a strong belief in God's love. This makes his voice different from other poets like Donne or Herbert.

What Crashaw Left Behind

Crashaw Prize

The Crashaw prize for poetry is given out by Salt Publishing.

Music Inspired by His Work

Crashaw's poems have been used in music. Composer Elliott Carter (1908–2012) was inspired by Crashaw's Latin poem "Bulla" ("Bubble"). He wrote a three-part orchestral piece called Symphonia: sum fluxae pretium spei (1993–1996).

The festival anthem Lo, the full, final sacrifice, Op. 26, was written in 1946 by British composer Gerald Finzi (1901–1956). It uses two of Crashaw's poems. These are "Adoro Te" and "Lauda Sion Salvatorem," which are Crashaw's translations of two Latin hymns.

"Come and let us live," Crashaw's translation of a poem by Roman poet Catullus, was set to music. It became a four-part choral song by Samuel Webbe, Jr. (1770–1843). Crashaw's "Come Love, Come Lord" was set to music by Ralph Vaughan Williams.

Parts of "In the Holy Nativity of our Lord" were set by American composer Alf Houkom (born 1935). This was part of his "A Christmas Meditation" (1986, revised 2018). "A Hymn of the Nativity" was set as "Shepherd's Hymn" by American composer Timothy Hoekman in 1992.

His Works

- 1634: Epigrammatum Sacrorum Liber (meaning "A Book of Sacred Epigrams")

- 1646: Steps to the Temple. Sacred Poems, With other Delights of the Muses

- 1648: Steps to the Temple, Sacred Poems. With The Delights of the Muses (an updated second edition)

- 1652: Carmen Deo Nostro (meaning "Hymns to Our Lord", published after his death)

- 1653: A Letter from Mr. Crashaw to the Countess of Denbigh Against Irresolution and Delay in matters of Religion

- 1670: Richardi Crashawi Poemata et Epigrammata (meaning "Poems and Epigrams of Richard Crashaw")

Modern Editions

- The Complete Works of Richard Crashaw, edited by Alexander B. Grosart, two volumes (London: printed for private circulation by Robson and Sons, 1872 & 1873).

- The Poems, English, Latin, and Greek, of Richard Crashaw edited by L. C. Martin (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1927); second edition, revised, 1957).

- The Complete Poetry of Richard Crashaw edited by George Walton Williams (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1970).

See also

In Spanish: Richard Crashaw para niños

In Spanish: Richard Crashaw para niños

- "On the Death of Mr. Crashaw", a poem about Crashaw by his friend, poet Abraham Cowley

| William Lucy |

| Charles Hayes |

| Cleveland Robinson |