Rowland Hill facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Sir Rowland Hill, KCB

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | 3 December 1795 Kidderminster, Worcestershire, England

|

| Died | 27 August 1879 (aged 83) |

| Resting place | Westminster Abbey |

| Nationality | British |

| Occupation | schoolteacher, social reformer, postal administrator |

| Known for | Uniform Penny Post |

| Awards | Albert Medal (1864) |

| Signature | |

Sir Rowland Hill (born December 3, 1795 – died August 27, 1879) was an English teacher, inventor, and social reformer. He worked hard to change the postal system in a big way.

His main idea was the Uniform Penny Post. This meant sending letters would be cheap and easy for everyone. He also came up with the idea of paying for postage beforehand, using a postage stamp. This made sending letters safe, fast, and affordable. Many people see him as the person who created the basic ideas for today's postal service.

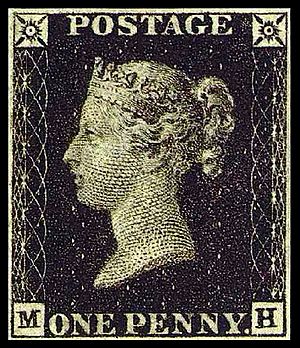

Hill believed that if it cost less to send letters, more people, even those with less money, would send them. This would eventually make more profit for the postal service. He suggested using a sticky stamp to show that postage was paid. The first stamp was the Penny Black. In 1840, the first year of the Penny Post, the number of letters sent in the UK more than doubled! Within 10 years, it doubled again. Soon, other countries like Switzerland, Brazil, and the US started using postage stamps too. By 1860, stamps were used in 90 countries.

Contents

Early Life and Family

Rowland Hill was born in Kidderminster, England. His father, Thomas Wright Hill, was a forward-thinking person in education and politics. He was friends with important thinkers like Joseph Priestley.

When Rowland was 12, he started helping teach at his father's school. He taught about stars and space (astronomy). He also earned extra money by fixing scientific tools. In his free time, he enjoyed painting landscapes.

In 1827, Rowland married Caroline Pearson. They had four children: Eleanor, Clara, Louisa, and Pearson.

Changing Education

In 1819, Rowland moved his father's school, "Hill Top," to a new place called Hazelwood School in Birmingham. He wanted Hazelwood to be a model for public education for the growing middle classes.

The school focused on teaching useful skills and knowledge. It aimed to help students learn on their own throughout their lives. Hill designed the school to include new things like a science lab, a swimming pool, and a heating system that blew warm air.

In his book Plans for the Government and Liberal Instruction of Boys in Large Numbers (1822), he wrote that kindness and good influence should guide school discipline, not fear or hitting. Science was a required subject, and students were encouraged to manage themselves.

Hazelwood School became famous around the world. A French education leader, Marc Antoine Jullien, visited and wrote about it. He was so impressed that he sent his own son there. The school also impressed Jeremy Bentham, a famous thinker. In 1827, a branch of the school opened in London at Bruce Castle. The original Hazelwood School closed in 1833, and its teaching ideas continued at the new Bruce Castle School. Hill was the headmaster there from 1827 to 1839.

Helping South Australia Grow

Rowland Hill was involved in the plan to create a new settlement in South Australia. This idea came from Edward Gibbon Wakefield, who thought that too many people in Britain caused social problems.

In 1832, Hill wrote a paper called Home colonies. It suggested a plan to reduce poverty and crime, based on a Dutch idea. From 1833 to 1839, Hill worked as the secretary for the South Australian Colonization Commission. This group successfully started a settlement in what is now Adelaide, without using convicts.

The new colony was meant to be a place that showed the best parts of British society. It valued religious freedom and worked towards social progress and civil liberties (basic rights).

Postal System Changes

Rowland Hill became very interested in changing the postal system in 1835. A Member of Parliament, Robert Wallace, gave him many books and papers to study. Hill spent a lot of time reading these documents.

In early 1837, he published a pamphlet called Post Office Reform its Importance and Practicability. He sent a copy to the government on January 4, 1837. This first version was private. The government official suggested improvements, and Hill added more information on January 28, 1837.

In the 1830s, the postal system in Britain had many problems. It was expensive, slow, and not well managed. It wasn't good enough for a country that was growing in business and industry.

One famous story, which might not be completely true, tells how Hill got interested in postal reform. He supposedly saw a young woman who couldn't afford to pay for a letter sent by her fiancé. Back then, the person receiving the letter usually paid for it. If they didn't want to pay, they could refuse the letter. People also found ways to cheat the system. For example, they might put secret messages on the outside of the letter. The receiver would read the message and then refuse to pay.

Also, the cost of sending letters was very complicated. It depended on how far the letter went and how many sheets of paper were used.

Richard Cobden and John Ramsey McCulloch, who believed in free trade, criticized the old postal system. McCulloch said in 1833 that "nothing contributes more to facilitate commerce than the safe, speedy and cheap conveyance of letters."

Hill's pamphlet, Post Office Reform, suggested "low and uniform rates" based on the letter's weight, not the distance it traveled. Hill and Charles Babbage found that most of the postal system's costs came from the difficult handling of letters at the start and end points, not from transport.

Costs could be greatly lowered if the sender paid for postage beforehand. This payment could be shown by using special prepaid letter sheets or sticky stamps. At that time, envelopes were not common. People would fold the letter itself to use for both the message and the address. Hill also suggested lowering the postage rate to one penny for half an ounce, no matter the distance. He first presented this idea to the government in 1837.

In the House of Lords, the Postmaster, Lord Lichfield, called Hill's ideas "wild and visionary." Another postal official, William Leader Maberly, said Hill's study was "preposterous."

However, business people like merchants, traders, and bankers thought the old system was unfair and hurt trade. They formed a "Mercantile Committee" to support Hill's plan. In 1839, Hill was given a two-year contract to manage the new postal system.

From 1839 to 1842, Hill lived at 1 Orme Square in London. There is a special plaque there to remember him.

The Uniform Fourpenny Post lowered the cost to fourpence starting December 5, 1839. Then, it dropped to the penny rate on January 10, 1840, even before stamps were printed. The number of paid letters sent inside the country increased a lot, by 120%, between November 1839 and February 1840. This first increase happened because special "free sending" rights and cheating were stopped.

Prepaid letter sheets, designed by William Mulready, were given out in early 1840. These Mulready envelopes were not very popular and people made fun of them. According to the British Postal Museum & Archive, stationery makers felt threatened by these envelopes and encouraged the jokes. They became so unpopular that the government used them only for official mail and destroyed many others.

However, these envelopes were actually an important step in printing. They showed that machine-printed illustrated envelopes could be made. Today, machine-printed illustrated envelopes are a big part of the direct mail business.

In May 1840, the world's first sticky postage stamps were released. They had a beautiful picture of the young Queen Victoria. The Penny Black was an instant hit. Later, improvements like perforations (small holes to make stamps easier to tear apart) were added to new stamps.

Later Life and Recognition

Rowland Hill continued working at the Post Office until a new government came into power in 1841. He was let go in July 1842.

However, the London and Brighton Railway company made him a director and later the chairman of their board, from 1843 to 1846. He lowered train fares, added more routes, offered special trips, and made train travel more comfortable.

In 1844, Rowland Hill and his friends formed a group called "Friends in Council." They met at each other's homes to talk about important topics like how countries manage their money and resources. Hill also joined the Political Economy Club, which included many powerful business and political figures.

In 1846, a new government came into power. Hill was made Secretary to the Postmaster General, and then Secretary to the Post Office from 1854 to 1864.

For all his hard work, Hill was made a Knight Commander of the Order of the Bath in 1860. This meant he was given the title "Sir." He also became a Fellow of the Royal Society and received an honorary degree from University of Oxford.

For the last 30 years of his life, Hill lived at Bartram House in Hampstead, London, where he passed away in 1879. He is buried in Westminster Abbey, a very famous church. There is also a memorial to him on his family grave in Highgate Cemetery. Streets are named after him in Hampstead and Tottenham. A Royal Society of Arts blue plaque also honors him in Hampstead.

Family Members

Rowland Hill was one of eight children.

- His brother, Matthew Davenport Hill (1792–1872), was a judge in Birmingham and worked to improve prisons.

- Another brother, Edwin Hill (1793-1876), was the first British Controller of Stamps. He invented a machine system to make envelopes.

- His brother Frederic Hill (1803-1896) was a prison inspector.

His Legacy and Memorials

Rowland Hill left two important legacies: 1. His ideas for educating the growing middle classes. 2. His plan for an efficient postal system to serve businesses and the public. This included the postage stamp and the system of low, unchanging postal rates.

He changed postal services around the world and made business more efficient. The Uniform Penny Post continued in the UK for a long time. At one point, one penny could send a letter weighing up to four ounces (about 113 grams)!

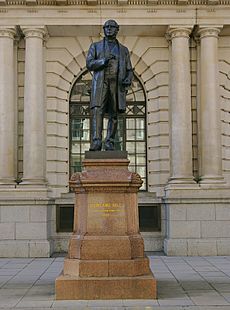

There are four public statues of Rowland Hill:

- One in Birmingham, made of marble, was unveiled in 1870. It is now in the Royal Mail sorting office in Newtown, Birmingham.

- A marble statue in Kidderminster, his birthplace, was unveiled in 1881. It is at the junction of Vicar and Exchange Streets. Kidderminster has a shopping center named The Rowland Hill Shopping Centre.

- In London, a bronze statue made in 1881 stands in King Edward Street.

- He is also included in a large sculpture in Dalton Square, Lancaster, called The Victoria Monument.

There are also two marble busts (head and shoulders sculptures) of Hill, both unveiled in 1881. One is in St Paul's Chapel, Westminster Abbey. Another is in Albert Square, Manchester.

Rowland Hill is honored at the Universal Postal Union (UPU), which is a UN agency that helps manage postal systems worldwide. One of the main meeting halls at the UPU headquarters in Berne, Switzerland, is named after him.

In Tottenham, north London, there is a local history museum at Bruce Castle (where Hill lived). It has some exhibits about him.

In Adelaide, South Australia, both Hill Street and Rowland Place are named in his honor.

The Rowland Hill Awards, started in 1997, are given each year for new and creative ideas related to stamps and postal history.

In 1882, the Post Office created the Rowland Hill Fund to help postal workers, retired staff, and their families who needed support. A similar fund was started in Ireland in 1928 and still helps people today.

Stamps Honoring Him

For the 100th anniversary of the first stamp, Portugal released a special sheet of stamps mentioning Rowland Hill. Later, on the 100th anniversary of his death, about 80 countries issued stamps to remember him. In total, 147 countries have issued stamps honoring Rowland Hill.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Rowland Hill para niños

In Spanish: Rowland Hill para niños

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |