Salar de Uyuni facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Salar de Uyuni |

|

|---|---|

| Salar de Tunupa (Spanish) | |

Hexagonal formations in the Salar de Uyuni during the dry season.

|

|

| Location | Daniel Campos Province, Potosí, Bolivia |

| Coordinates | 20°08′01.59″S 67°29′20.88″W / 20.1337750°S 67.4891333°W |

| Elevation | 3,663 metres (12,018 ft) |

| Length | average of 126 km (78 mi) |

| Width | average of 84 km (52 mi) |

| Area | 10,582 square kilometres (4,086 sq mi) |

| Depth | 130 metres (430 ft) |

| Formed by | Evaporation |

| Geology | Salt pan |

The Salar de Uyuni is the world's largest salt flat! Imagine a giant, flat area covered in salt, stretching for about 10,582 square kilometers (that's roughly the size of a small country!). You can find it in southwestern Bolivia, high up in the Andes Mountains. It sits at an elevation of about 3,656 meters above sea level, which is pretty high!

This amazing place was formed thousands of years ago when several ancient lakes dried up. Today, it's covered by a thick layer of salt, which is incredibly flat – the ground barely changes height across the entire area. This salt crust hides a pool of salty water called brine, which is super rich in a special metal called lithium. Lithium is used in batteries for many of our electronic devices!

The Salar de Uyuni is also famous for something truly magical: after it rains, a thin layer of calm water turns the entire flat into the world's biggest natural mirror. It reflects the sky perfectly, creating breathtaking views! Because it's so large, flat, and clear, scientists even use it to help calibrate satellites that orbit Earth.

Besides being a stunning natural wonder, the Salar is an important travel route across the Bolivian Altiplano. It's also a vital breeding ground for several types of flamingos. You might have even seen it in movies like Star Wars: The Last Jedi!

Contents

- What's in a Name? The Meaning of Salar de Uyuni

- How Salar de Uyuni Formed: A Look at its Geology and Climate

- Salar de Uyuni's Economic Importance: Salt and Lithium

- Exploring Salar de Uyuni: Hotels and Train Cemetery

- Salar de Uyuni: A Natural Lab for Satellites

- Wildlife and Plants: Life in the Salar de Uyuni

- Images for kids

- See also

What's in a Name? The Meaning of Salar de Uyuni

The name Salar simply means "salt flat" in Spanish. The word Uyuni comes from the Aymara language, an ancient language spoken in the Andes. It means "a pen" or "an enclosure." Uyuni is also the name of a nearby town, which is often the starting point for tourists visiting the salt flat.

There's a local legend from the Aymara people about how the Salar was formed. They say that the mountains surrounding the Salar – named Tunupa, Kusku, and Kusina – were once giants. Tunupa was married to Kusku, but Kusku left her for Kusina. Tunupa was so sad that she cried while feeding her baby. Her tears mixed with her milk, and this mixture created the vast Salar. Many local people still see Tunupa as a very important figure and believe the place should be called Salar de Tunupa instead of Salar de Uyuni.

How Salar de Uyuni Formed: A Look at its Geology and Climate

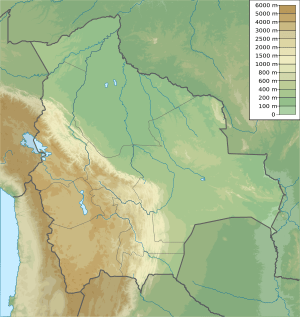

The Salar de Uyuni is located in the Altiplano region of Bolivia, a high plateau in South America. This plateau was formed when the mighty Andes Mountains rose up over millions of years. The Altiplano has many lakes and salt flats, and it's a "closed basin," meaning water flows into it but doesn't flow out to the ocean.

The history of the Salar is like a story of giant lakes changing over time. About 30,000 to 42,000 years ago, this area was covered by a huge prehistoric lake called Lake Minchin. Over time, this lake transformed into other large lakes, like Paleo Lake Tauca and then Lake Coipasa. Eventually, these lakes dried up, leaving behind the two modern lakes we see today (Lake Poopó and Uru Uru) and two massive salt deserts: the Salar de Coipasa and the even larger Salar de Uyuni.

The Salar de Uyuni is enormous, covering about 10,582 square kilometers. That's roughly 100 times bigger than the famous Bonneville Salt Flats in the United States! During the wet season, water from nearby Lake Titicaca can flow into Lake Poopó, which then sometimes floods parts of the Salar de Coipasa and Salar de Uyuni.

Underneath the solid salt crust of the Salar, there's a layer of muddy material mixed with salt, all soaked in a super salty water called brine. This brine is full of different salts, including sodium chloride (table salt), lithium chloride, and magnesium chloride. The salt crust on top can be anywhere from a few centimeters to several meters thick. In the middle of the Salar, you can find a few islands. These are actually the tops of ancient volcanoes that were once submerged when the area was a giant lake. They have cool, fragile, coral-like structures and fossils from ancient algae.

Climate: Weather in the Salt Flat

The Salar de Uyuni has a fairly steady average temperature. It's warmest from November to January, reaching about 21°C. The coolest months are around June, with temperatures around 13°C. However, the nights are cold all year round, often dropping below freezing.

The air is usually quite dry, with low humidity. Most of the year, there's very little rain, just 1 to 3 millimeters per month between April and November. But in January, during the rainy season, rainfall can increase quite a bit, sometimes up to 80 millimeters. Even then, it usually only rains a few days a month.

Salar de Uyuni's Economic Importance: Salt and Lithium

The Salar de Uyuni is incredibly rich in natural resources. It's part of what's called the "Lithium Triangle" because it holds huge amounts of sodium, potassium, lithium, and magnesium. These are all found in different salt forms.

As of 2024, Bolivia has about 22% of the world's known lithium resources, which is an estimated 23 million tons! Most of this lithium is right here in the Salar de Uyuni. Lithium is a very important metal because it's used to make batteries for our phones, laptops, and electric cars.

The lithium is found in the salty water (brine) beneath the salt crust. It's relatively easy to get out: workers drill into the crust and pump the brine to the surface. Scientists have even used satellites to map where the brine is located!

For a long time, there were discussions about how to extract this valuable lithium. In the 1980s and 1990s, some foreign companies tried to get involved, but local communities strongly disagreed. They wanted to make sure that any money made from mining would benefit the people living nearby. Also, the lithium in the Salar has some impurities, and the wet climate and high altitude make it a bit harder to process.

Currently, there isn't a large-scale mining plant at the site. The Bolivian government has aimed to develop lithium production itself, working with a German company, and had aimed to reach an annual production of 35,000 tons by 2023.

The Salar de Uyuni is also estimated to contain about 10 billion tons of regular salt! Less than 25,000 tons of this salt are extracted each year. All the salt miners working here belong to a cooperative from the town of Colchani. Because of its huge, flat area, the Salar is also a major route for cars and trucks traveling across the Bolivian Altiplano, except when it's covered by water during the rainy season.

Exploring Salar de Uyuni: Hotels and Train Cemetery

The Salar de Uyuni is a very popular place for tourists, and because of this, several unique hotels have been built in the area. Since it's hard to find regular building materials in the middle of a salt flat, many of these hotels are made almost entirely out of salt blocks cut right from the Salar! This includes the walls, roofs, and even some of the furniture.

The very first salt hotel, called Palacio de Sal, was built between 1993 and 1995. It became very popular, but its remote location caused some challenges with waste management. To protect the environment, the original hotel was taken down in 2002. Around 2007, a new Palacio de Sal was built in a different spot, closer to the edge of the Salar and the town of Uyuni. This new hotel was designed to meet environmental rules and even has cool features like a dry sauna, steam room, and saltwater pool!

The Train Cemetery: A Glimpse into the Past

Another fascinating place to visit is the antique train cemetery, located just 3 kilometers outside of Uyuni. Old train tracks connect it to the town. Long ago, Uyuni was an important hub where trains carried minerals from mines to ports on the Pacific Ocean.

British engineers built these railway lines between 1888 and 1892. This project was supported by Bolivian President Aniceto Arce, who believed a good transport system would help Bolivia grow. However, local Aymara people sometimes interrupted the construction, as they saw it as an intrusion. These trains were mostly used by mining companies. In the 1940s, the mining industry slowed down, partly because the minerals started to run out. Many trains were then abandoned, creating the unique train cemetery we see today. There are even ideas to turn it into a museum!

Staying Safe on Tours

When exploring the Salar de Uyuni, it's really important to choose a safe and reliable tour company. There have been times when tours faced problems due to vehicles that weren't well-maintained, drivers who were speeding, or not being careful enough in the challenging environment. Always make sure your tour operator prioritizes safety to have the best and safest adventure!

Salar de Uyuni: A Natural Lab for Satellites

Because it's the largest salt flat on Earth, the Salar de Uyuni is an amazing natural place for calibrating satellites! Think of "calibrating" as fine-tuning or checking a satellite's instruments to make sure they are giving accurate measurements.

The Salar is perfect for this because it has an incredibly high albedo – meaning it reflects most of the sunlight that hits it. Plus, it's huge and super flat, making it a very uniform surface. These features, along with its high altitude (3,650 meters above sea level), stable light reflection, and minimal radio interference, create ideal conditions for scientists. Space agencies and researchers use the Salar to calibrate both radar and optical sensors on their satellites. The elevation across its 10,582 square kilometer surface varies by less than one meter, which is incredibly flat compared to the Earth's size! This makes the Salar de Uyuni about five times better for satellite calibration than the open ocean.

Many important space missions have used the Salar. In September 2002, NASA's ICESat-2 mission conducted detailed GPS surveys there. This helped them calibrate their laser altimeters, which are instruments that measure height, to create super-accurate digital elevation models of Earth's surface. The Landsat 5 satellite also used the Salar to calibrate its cameras, especially for visible and near-infrared light.

More recently, in April 2014, the European Space Agency’s (ESA) Sentinel-1A satellite surveyed the Salar shortly after its launch. This mission focused on calibrating radar measurements of the Earth's surface. ESA's CryoSat-2 mission, launched in 2010 to monitor ice thickness and sea levels, also relies on the Salar to improve the accuracy of its altimeter observations. And in February 2024, the Copernicus Sentinel-3B mission performed calibration activities over the Salar for its radar altimeter.

Wildlife and Plants: Life in the Salar de Uyuni

The Salar de Uyuni might seem like a barren place, but it's home to some unique plants and animals!

The plant life is mostly made up of giant cacti, like the Echinopsis atacamensis pasacana. These impressive cacti grow very slowly, about 1 centimeter per year, but can reach heights of up to 12 meters (about 40 feet)! Other shrubs you might find include Pilaya, which locals use for traditional remedies, and Thola (Baccharis dracunculifolia), which is sometimes burned as a fuel. You can also spot quinoa plants and queñua bushes.

Flamingos and Other Birds: Reproduction and Life Cycle

Every November, the Salar de Uyuni becomes a crucial breeding ground for three beautiful species of flamingos found in South America: the Chilean flamingo, the Andean flamingo, and the rare James's flamingo. These flamingos feast on tiny brine shrimps that live in the salty water.

About 80 other bird species also visit or live in the area, including the horned coot, Andean goose, and Andean hillstar.

Mammals of the Salar

You might also spot the Andean fox, also known as a culpeo. And on the islands within the Salar, especially Incahuasi Island, you can find colonies of rabbit-like viscachas.

Images for kids

-

A part of Incahuasi Island inside the Salar, featuring giant cacti

-

Bolivian vizcacha

-

Andean flamingos in the Laguna Colorada, south of the Salar

See also

In Spanish: Salar de Uyuni para niños

In Spanish: Salar de Uyuni para niños

| Laphonza Butler |

| Daisy Bates |

| Elizabeth Piper Ensley |