Sand Creek massacre facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Sand Creek massacre |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Colorado War, American Indian Wars, American Civil War | |||||||

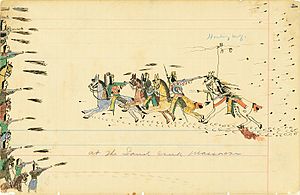

A depiction of one scene at Sand Creek by witness Howling Wolf |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Cheyenne Arapaho |

|||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

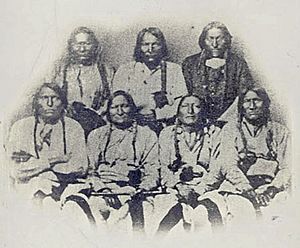

| Black Kettle | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 700 | 70–200 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 25 killed 51 wounded |

69–600 (mostly women and children) killed | ||||||

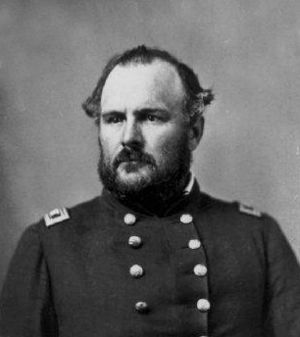

The Sand Creek massacre was a terrible event that happened on November 29, 1864. It is also known as the Chivington massacre. During this event, a group of about 675 U.S. Army soldiers, led by Colonel John Chivington, attacked a peaceful village of Cheyenne and Arapaho people. This village was located in southeastern Colorado Territory.

The attack resulted in the deaths of many Native American people, mostly women and children. Estimates of those killed range from 69 to over 600. The soldiers claimed they killed many warriors, but most reports say around 150 people died. Today, the place where this happened is called the Sand Creek Massacre National Historic Site. It is managed by the National Park Service and helps us remember this sad part of history. This massacre was a major event in the Colorado War.

Contents

Why Did the Conflict Start?

Early Treaties and Land Changes

In 1851, the United States made a deal called the Treaty of Fort Laramie with several Native American nations, including the Cheyenne and Arapaho. This treaty said that the Cheyenne and Arapaho owned a huge area of land. This land stretched from the North Platte River to the Arkansas River and from the Rocky Mountains to western Kansas.

However, in 1858, gold was found in the Rocky Mountains. This led to the Pikes Peak Gold Rush, and many people rushed into the area. These new settlers moved onto Cheyenne and Arapaho lands. They competed for resources like water and hunting grounds. Because of this, officials in Colorado wanted to change the size of the Native American lands.

New Treaties and Smaller Lands

In 1861, some Cheyenne and Arapaho chiefs signed a new agreement called the Treaty of Fort Wise. In this treaty, they gave up most of the land they had been promised in the 1851 treaty. The new area was much smaller, less than one-thirteenth of the original size. It was located in eastern Colorado, between the Arkansas River and Sand Creek.

Many Cheyenne warriors, especially a group called the Dog Soldiers, were very angry about this new treaty. They said the chiefs who signed it did not have the right to do so. They also believed the chiefs were tricked or bribed. These groups refused to follow the new treaty. They continued to live and hunt in their traditional lands, which were rich in bison. Tensions grew as more white settlers moved into these areas.

Growing Tensions and Attacks

By late 1863 and early 1864, there were rumors that different Native American tribes were planning to unite and "drive the whites out." In the spring and summer of 1864, groups like the Sioux, Comanches, Kiowas, Cheyennes, and Arapahos were involved in conflicts. These conflicts led to attacks on settlers, destruction of farms, and disruptions to supply routes. Settlers in Colorado felt unsafe.

For example, in April, Cheyenne and Arapaho groups took oxen and horses from a company south of Denver. Soldiers sent to get the animals back were attacked, and four soldiers died. Later, in May, a Cheyenne chief named Lean Bear tried to show he was peaceful to soldiers from the 1st Colorado Regiment. He wore a peace medal and carried a document from President Lincoln. But the soldiers, under orders from Colonel John Chivington, shot and killed him.

The American Civil War was happening at this time, so the U.S. government was focused on fighting the Confederates. This meant there wasn't much military protection for settlers in Colorado. Attacks on wagon trains and settlements became common. Many settlers left their homes and moved to safer towns like Denver. In August 1864, all stagecoach lines in the region were attacked. Colorado Governor John Evans asked for more military help, and eventually, a new group of soldiers, the Third Colorado Volunteers, was formed.

Before the Sand Creek Massacre, there were 32 recorded Native American attacks in 1864. These attacks resulted in 96 settlers killed, 21 wounded, and eight captured. Many animals were stolen, and wagon trains and ranches were attacked.

I am not a big war chief, but all the soldiers in this country are at my command. My rule of fighting white men or Indians is to fight them until they lay down their arms and submit to military authority. They are nearer to Major Wynkoop than any one else, and they can go to him when they get ready to do that.

- Col. John Milton Chivington, September 28, 1864 peace council in Denver

Governor Evans's Warning

As the conflict continued, Native American tribes would fight in the spring and summer. Then, when winter made it hard to find food, they would try to make peace. In July 1864, Governor John Evans sent a message to the Plains Indians. He invited friendly tribes to go to Fort Lyon for safety and protection.

However, when Cheyenne chiefs came to Denver for peace talks on September 28, Governor Evans told them that peace was not possible with him. He said they had to make peace with the soldiers. He also warned them that there was a "great danger" that soldiers might kill some of their people. Colonel Chivington, who was also there, told the chiefs that if they wanted peace, they should go to Fort Lyon and be protected by Major Wynkoop.

About 652 Arapahos went to Fort Lyon in November 1864 and received supplies. But when 600 Cheyenne arrived, they were turned away and not given food or protection. This showed the mixed and confusing messages the Native Americans received.

The Attack on Sand Creek

The Cheyenne Camp

Black Kettle, a leading chief of the Southern Cheyenne, had brought his group, along with some Arapahos, to Fort Lyon. He did this because he believed it would lead to peace, as discussed in Denver. Later, the Native Americans were told to move their camp to Big Sandy Creek, about 40 miles away.

The Dog Soldiers, who were more focused on fighting, were not part of this camp. The camp at Sand Creek had about 75 men, mostly older or very young, along with many women and children. Black Kettle showed his peaceful intentions by flying a U.S. flag with a white flag tied below it over his lodge. This was what the Fort Lyon commander had told him to do. Peace chief Ochinee was among those in the camp.

Grandfather Ochinee (One-Eye) escaped from the camp, but seeing all that his people were to be slaughtered, he deliberately chose to go back into the one-sided battle and die with them.

- Mary Prowers Hudnal, daughter of Amache Prowers

Chivington's Attack

On November 28, 1864, Colonel Chivington arrived at Fort Lyon with 425 men from the 3rd Colorado Cavalry. He then took command of more soldiers and headed towards Black Kettle's camp. James Beckwourth, a famous frontiersman who knew Native Americans well, guided Chivington.

Before the attack, some officers, like Captain Silas Soule and Lieutenant Joseph Cramer, disagreed with Chivington. They argued that attacking a peaceful camp would break the promise of safety given to the Native Americans.

The next morning, Chivington ordered the attack. Captain Soule and Lieutenant Cramer refused to obey and told their men not to fire. However, the rest of Chivington's soldiers immediately attacked the village. They ignored the U.S. flag and the white flag of surrender that was raised. The soldiers killed as many Native Americans as they could.

The Native Americans in the camp had no cannons and could not fight back effectively. Some tried to escape by riding horses up Sand Creek or by digging holes in the sand under the creek banks. Many were chased and shot, but some survived. A Cheyenne warrior named Morning Star said that most of the deaths were caused by cannon fire.

Reports on the number of deaths vary. Historian Alan Brinkley stated that 133 Native Americans were killed, with 105 of them being women and children. George Bent, who was in the village and wounded during the attack, later said that 137 people were killed: 28 men and 109 women and children. Another time, he said about 53 men and 110 women and children were killed. For the soldiers, 24 were killed and 52 were wounded.

What Happened After the Massacre?

The Sand Creek Massacre caused a huge loss of life, especially among Cheyenne and Arapaho women and children. Black Kettle's group, the Wutapiu, was hit the hardest. Many chiefs who had worked for peace were killed, including White Antelope and One Eye. This event greatly weakened the traditional Cheyenne leadership.

Survivors hid in holes along the creek or fled. After a cold night, they made their way to another Cheyenne camp on the Smoky Hill River, where they found help.

The massacre also made the split worse between the traditional Cheyenne chiefs, who wanted peace, and the younger, more aggressive Dog Soldiers. The Dog Soldiers believed the massacre proved that trying to make peace with white settlers was a mistake. They felt their strong stance against the whites was justified.

Revenge Attacks

After the massacre, many Cheyenne and Arapaho, including the famous warrior Roman Nose, joined the Dog Soldiers. They sought revenge on settlers. In January 1865, about 1,000 warriors attacked a stagecoach station and fort near present-day Julesburg, Colorado. They then carried out many raids along the South Platte River, stealing goods and killing settlers. Most of these Native American groups then moved north towards the Black Hills.

Black Kettle, however, continued to seek peace. He did not join these revenge attacks and instead returned to the Arkansas River with his group to try and make peace with the Coloradans.

Official Investigations and Findings

At first, the Sand Creek event was called a victory. But soon, witnesses and survivors began to tell stories of a massacre. Several investigations were launched by the military and by a special committee of the U.S. Congress.

The Congressional committee strongly condemned Colonel Chivington's actions. They said he "deliberately planned and executed a foul and dastardly massacre." They noted that he knew the Native Americans were friendly and had been promised safety. The committee recommended that those responsible be removed from office and punished.

Captain Silas Soule, who had refused to fire his weapons during the attack, gave important testimony against Chivington. Sadly, he was murdered in Denver just weeks after speaking out. Despite the strong findings, no charges were brought against Chivington because he had already resigned from the army. His political career, however, was effectively over.

Some people, like cavalryman Irving Howbert, defended Chivington. Howbert claimed that Native American women and children were not targeted and that the number of warriors in the village was equal to the soldiers. He said Chivington was retaliating for earlier Native American attacks.

In 1909, a monument in Colorado listed Sand Creek as a "battle." But in 2002, the Colorado Historical Society added a new plaque. This plaque states that the original monument "mischaracterized" Sand Creek by calling it a battle, acknowledging it was a massacre.

Later Treaties and Broken Promises

After the truth about the massacre became widely known, the U.S. government sent a special group to negotiate. The Little Arkansas Treaty was signed in 1865. It promised the Native Americans free access to lands south of the Arkansas River and offered land and money to the families of Sand Creek victims.

However, this treaty was canceled by Washington less than two years later. Most of its promises were ignored. Instead, the Medicine Lodge Treaty greatly reduced the reservation lands, moving them to less desirable areas in Oklahoma. Later government actions further reduced these lands.

Remembering Sand Creek

Today, the site of the massacre, on Big Sandy Creek in Kiowa County, is preserved by the National Park Service. The Sand Creek Massacre National Historic Site was opened on April 28, 2007, almost 142 years after the event.

The Sand Creek Massacre Trail in Wyoming follows the paths taken by the Northern Arapaho and Cheyenne after the massacre. It traces their journey to the Wind River Indian Reservation, where the Arapaho live today. Young Arapaho people sometimes run the length of this trail to honor their ancestors.

In 2012, an exhibit about Sand Creek opened at the History Colorado Center in Denver. However, it received criticism from the Northern Cheyenne tribe. In 2013, History Colorado agreed to close the exhibit temporarily to talk with the tribe.

On December 3, 2014, Colorado Governor John Hickenlooper formally apologized to the descendants of the Sand Creek massacre victims. He said, "On behalf of the State of Colorado, I want to apologize. We will not run from this history." In 2015, a memorial to the victims began construction at the Colorado Capitol grounds.

Sand Creek in Popular Culture

The Sand Creek massacre has been shown or mentioned in many books, movies, and TV shows.

Comics

- Nemesis the Warlock in 2000 AD #504 (1986) shows the massacre.

- The 30th chapter of the Italian comic book series Storia del West by Gino D'Antonio includes themes of the massacre.

Films

The massacre has been shown in several western movies:

- Tomahawk (1951)

- Massacre at Sand Creek (1956)

- The Guns of Fort Petticoat (1957)

- Soldier Blue (1970)

- The Last Warrior (1970)

- Young Guns (1988)

- Last of the Dogmen (1995)

- Little Big Man (1970) has an early scene of the Sand Creek Massacre.

- It is also mentioned in Iron Man 3 (2013).

Literature

- Sulle frontiere del Far-West (1909) by Emilio Salgari

- Cheyenne Autumn (1953) by Mari Sandoz

- A Very Small Remnant (1963) by Michael Straight

- Centennial (1974) by James Michener

- From Sand Creek (1981) by Simon Ortiz

- Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee (1971) by Dee Brown

- The Massacre at Sand Creek (1995) by Bruce Cutler

- Flight (2007) by Sherman Alexie

- Choke Creek (2009) by Lauren Small

- Young Sherlock Holmes: Fire Storm (2011) by Andrew Lane

- Remembering the Sand Creek Massacre: A Historical Review of Methodist Involvement, Influence, and Response (2016), by Gary L. Roberts

- There There (2018) by Tommy Orange includes a fictionalized version of the event.

- The Minutes by Tracy Letts uses a fictionalized version of the event as a key part of the story.

Music

Songs about Sand Creek include:

- Dreadzone's "Scalplock"

- Gila's "Black Kettle's Ballad"

- Five Iron Frenzy's "Banner Year"

- Peter La Farge's "The Crimson Parson"

- Fabrizio De André's "Fiume Sand Creek"

- J.D. Blackfoot's "The Song of Crazy Horse"

Television

- In the episode "Old Jake" (1957) of The Life and Legend of Wyatt Earp, a character is a former soldier who participated in the massacre.

- The television series Tales of Wells Fargo (1958) includes a segment about the aftermath of the massacre.

- The Gunsmoke episode "The Drummer" (1972) describes a similar event called the Rock Creek Massacre.

- The 1978 miniseries Centennial includes the Sand Creek massacre in Episode 5, "The Massacre."

- The Dr. Quinn, Medicine Woman episode "A Cowboy's Lullaby" (1993) mentions the massacre as a reason why a Cheyenne tribe would not adopt a half-white infant.

- The West (1996) depicts the Sand Creek massacre in Episode 4.

- The 2005 miniseries Into the West includes the Sand Creek massacre in Episode 4, "Hell on Wheels."

See also

In Spanish: Masacre de Sand Creek para niños

In Spanish: Masacre de Sand Creek para niños

| Tommie Smith |

| Simone Manuel |

| Shani Davis |

| Simone Biles |

| Alice Coachman |