Schuylkill and Susquehanna Navigation Company facts for kids

Contents

- William Penn's Early Idea for Pennsylvania

- Society for Improving Roads and Waterways

- The Schuylkill and Susquehanna Navigation Company

- Legacy and Impact

- Images for kids

The Schuylkill and Susquehanna Navigation Company was a company started in Pennsylvania on September 29, 1791. Its main goal was to make rivers easier to travel on. In the 1790s, this meant clearing rivers like the Susquehanna and Schuylkill and building dams.

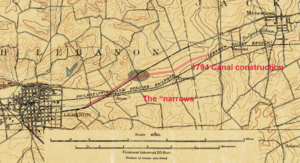

The company also planned to build a special canal to connect these two rivers. This canal would be about four miles long at its highest point, near Lebanon, Pennsylvania. It was meant to be part of a water route from Philadelphia all the way to Lake Erie and the Ohio Valley.

Engineers first thought about building a canal up the Schuylkill Valley to Norristown, then improving the Schuylkill River to Reading. From Reading, another canal would go to the Susquehanna River, passing through Lebanon. This would have created a four-mile "summit-level canal" between the Tulpehocken and Quitipahilla creeks. A summit-level canal is one that goes uphill and then downhill, connecting two different river valleys. This canal would have been the first of its kind in the United States. It was supposed to be a "golden link" connecting Philadelphia to the vast lands of Pennsylvania and beyond.

Building this canal was a huge challenge for engineers in the 1700s. They had to design a water system in an area where the ground had many sinkholes and not much surface water. The plan from 1794 had a big problem: there wasn't enough water to keep the canal full at the summit. Also, the technology to stop water from leaking was still a century away. The company's later version, the Union Canal, faced the same issues trying to seal the canal bed. The summit crossing never worked well for canal boats. Even with two water storage areas (reservoirs) at the summit, the Union Canal still needed pumps to bring water from nearby creeks. These pumps were powered by steam engines, a technology that existed in 1828 when the Union Canal opened, but not in 1791.

By 1885, the Union Canal was sold because it couldn't compete with railroads. It also struggled with poor planning and the difficult ground conditions in Lebanon County, Pennsylvania. If the Schuylkill and Susquehanna Navigation Company had finished the canal in the 1790s, it probably would have faced the same problems.

Despite these issues, people were very excited about this project in 1791. They believed Pennsylvania could become a major trade center, just like New York did later with the Erie Canal. But by 1795, the company's project had failed. This meant Philadelphia lost its early lead in water transportation. In 1796, Philadelphia's trade was much bigger than New York's. But by 1825, after the Erie Canal opened, Philadelphia's trade was much smaller than New York's.

New York's rise to become the most important American city wasn't a sure thing. In 1791, Philadelphia was the leading city. People expected it to grow even more as the country became independent. Instead, Philadelphia fell to second place. By 1807, New York was the main business city. By 1837, it was the biggest city in America. Philadelphia's failure to build the "golden link" canal 30 years before New York opened the Erie Canal was a big reason for this change.

William Penn's Early Idea for Pennsylvania

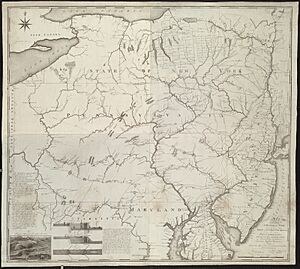

The idea of connecting the Schuylkill River and Susquehanna River with a canal was first talked about by William Penn in 1690. Penn, who founded Philadelphia, wanted to create a "second settlement" on the Susquehanna River, similar in size to Philadelphia. He shared this plan in England in 1690.

Penn imagined a road going up the west side of the Schuylkill River to French Creek, near what is now Phoenixville, Pennsylvania. From there, it would go west to the Susquehanna River, passing through Lancaster, Pennsylvania and along the Conestoga River. Even though Penn was the first to suggest continuous water travel from the Delaware to the Susquehanna, he didn't specifically call for a canal.

Early Requests for River Improvements

In 1762, merchants in Philadelphia asked the Pennsylvania Provincial Assembly to start a project. They wanted to make it possible to travel by water up the West Branch Susquehanna River, with a short land journey (portage) to a part of the Ohio River that boats could use. In 1769, another request asked the Province to make the Juniata River easy to navigate down to the Susquehanna River. Both requests failed, and neither mentioned canals as a necessary part of the plan.

River Surveys from 1769 to 1773

In 1769, the American Philosophical Society, with Benjamin Franklin as its first president, started a committee on "American Improvements." One of their first projects was to study a canal between the Chesapeake and Delaware bays. They looked at different routes.

In August 1771, the committee learned about the idea of joining the Susquehanna and Schuylkill rivers with a canal. A key part of their study focused on the "summit level." This was a four-and-a-half-mile stretch between the sources of the Quittapahilla Creek (near Lebanon, Pennsylvania) and Tulpehocken Creek (near Myerstown, Pennsylvania). Dr. William Smith and John Lukens led this survey. They were impressed by how practical a canal on the Tulpehocken-Swatara route seemed.

The Society suggested a third canal route that same year. The Pennsylvania Provincial Assembly then formed its own committee to survey the Susquehanna, Schuylkill, and Lehigh Rivers. In 1773, David Rittenhouse gave his report. But nothing came of this work because the American Revolution began.

Society for Improving Roads and Waterways

After the Revolution, the idea of connecting the rivers became a goal for the Society for the Improvement of Roads and Inland Navigation. This group was formed in 1789, with famous financier Robert Morris as its president. The Society asked the government to survey the river routes again, and this time, the State agreed.

Pennsylvania State River Surveys of 1790

In the spring of 1790, the government approved river surveys. Governor Thomas Mifflin asked Timothy Matlack, Samuel Maclay, and John Adlum to survey several rivers. These included the Swatara, the West Branch of the Susquehanna, and the Allegheny River. They also looked at routes to Lake Erie and the Ohio River.

Other survey teams were also appointed. One team reported that Conowago Falls on the Susquehanna River was a major obstacle. They believed a canal was the best way to allow boats to pass.

In April 1790, Samuel Maclay surveyed the Swatara and Quitapahilla Creeks. He noted that the Quitapahilla could be made navigable for small boats. Maclay and the other surveyors found that most waterways could be improved. However, they suggested short land crossings (portages) to save money. This included the four-mile Lebanon summit crossing.

In February 1791, reports suggested improvements for the Delaware River and the Schuylkill River. They also recommended a road or canal from Reading to the Susquehanna River.

Connecting the Susquehanna and Schuylkill Rivers

In its 1791 report, the Society suggested using the Schuylkill River from Philadelphia up to Tulpehocken Creek, near Reading. Then, they would continue up the Tulpehocken as far as possible. The Society still needed to figure out how to cross the summit near Lebanon to connect to the Quitapahilla and Swatara creeks, which led to the Susquehanna River.

The proposed distances were:

- Up the Schuylkill River from Philadelphia to Tulpehocken Creek: 61 miles.

- Westward, up Tulpehocken Creek to the east end of the summit canal: 37 miles. They planned to clear 30 miles of the creek and dig a canal for the last 7 miles. About ten locks would be needed to go up this distance.

- Length of the summit canal: 4 miles. This part would be a canal about 25 feet deep and 30 feet wide.

- Down Quitipahilla to Swatara: 15 miles.

- Down Swatara to Susquehanna River: 23 miles.

In the 1790s, "navigation" mostly meant improving existing river systems. For example, the Western Inland Lock Navigation Company in New York, which later became part of the Erie Canal, was also mainly a river system. In Pennsylvania, the plan was to clear large rivers like the Susquehanna and Schuylkill. These larger river parts would be connected by short canals or land crossings.

One writer noted that the Society lacked knowledge about canals, which were new in America. They weren't sure if a canal or a "lock navigation" system would be cheaper for the summit crossing. The Society estimated the total cost of improving the Schuylkill River and connecting it to the Susquehanna at about £55,540 (in 1791 money). This is about $8.6 million in 2018 US dollars. The companies that eventually finished this project, the Schuylkill Navigation Company and the Union Canal, spent about $2.8 million (in 1830 money), which is about $73 million in 2018 US dollars. This was roughly nine times the original estimate.

Brindley's Surveys in 1791

James Brindley (1745-1820), a well-known canal engineer from Britain, was in Delaware in 1791. He had worked on several canals in the US. In 1791, the Society asked him to re-survey the 1771 summit route for the canal between the Tulpehocken and Quittapahilla Creeks. Brindley and his team completed the survey and created a map for the summit canal. They found that there was enough water at the summit to supply the canal. The Society later asked the new Schuylkill and Susquehanna Navigation company to pay for this survey.

In 1791, the Society suggested to the State that they connect the Atlantic coast with Lake Erie. This Pennsylvania plan came before New York's similar plans for the Erie Canal in 1792. The Society proposed a 426-mile canal route connecting Philadelphia with Pittsburgh. Part of this project was a canal segment up the Schuylkill River to Tulpehocken Creek, then to a summit-level canal near Lebanon, Pennsylvania, and finally to the Susquehanna River using the Quittapahilla Creek and Swatara creeks.

This led to the creation of two companies. The first was the Schuylkill and Susquehanna Navigation Company, started on September 29, 1791. Its goal was to connect the Schuylkill and Susquehanna rivers from Reading to Middletown. The second was the Delaware and Schuylkill Navigation Company, started in 1792, to build a canal between the Schuylkill and Delaware rivers. Robert Morris was the president of both companies.

Taking Land for the Canal

The 1791 law that created the company had a detailed process for taking private land and water for the canal. This process became a model for later canal laws in Pennsylvania. Before this, companies only paid for damages to improved lands. But this new law required the company to pay for all damages when they used their power to take any land, water, or materials needed for the canal. This included mills and water sources.

This caused big worries for canal companies like the Schuylkill and Susquehanna Navigation Company because of the high costs of these damages. An officer of the company said in 1807 that they couldn't finish the canal partly because of the "enormous sums paid for land and water rights."

Starting the Company

In early 1792, the company was officially started in Philadelphia. Robert Morris, a famous financier, was president. Tench Francis was Treasurer, and Timothy Matlack, who wrote out the United States Declaration of Independence, was Secretary. Many other important people from Philadelphia were also directors. Even George Washington received one share of stock in the company.

To get people to buy stock, the company had to advertise in three newspapers for a month, including one in German. They could sell 1,000 shares. If too many people wanted to buy, they would use a lottery to decide who got shares. No one person could own more than ten shares at first.

Funding the Company

When Robert Morris and others were starting the company, there was a lot of money flowing into the Delaware Valley. This was because bad harvests in Europe created a high demand for American farm products. Also, the government's economic plan helped make investing in new companies very popular.

Philadelphia's exports grew a lot during this time. The Schuylkill and Susquehanna Navigation company was supposed to be the "golden link" that would connect Philadelphia's trade with the vast Susquehanna River valley.

The "Philadelphia Fever" and the 1792 Panic

On December 1, 1791, the company started selling stock. Within an hour, more than the minimum needed shares were bought. After 15 days, 46,000 shares were subscribed! This showed a "speculative spirit" where people were eager to invest, hoping for quick profits. The number of shares was later reduced to 1,000 by lottery.

A few months later, the first financial panic in the new United States happened in 1792. This made it hard for people to pay for their stock. The company agreed to accept promissory notes instead of cash.

This period also saw a lot of land speculation in Northern Pennsylvania. Speculators like Robert Morris used land they barely owned to get loans. The canal company promised more trade and settlement, which would raise land values. Morris and other managers started many land companies between 1793 and 1797. This "speculative bubble" burst in 1796, just when the navigation company needed money for its operations. Many speculators, including Robert Morris, ended up in debt. This also slowed down the development of a large part of Pennsylvania for many years.

Building the Canal

There were very few trained civil engineers in the United States when the company started. Early planning was done by surveyors like John Lukens and David Rittenhouse. Besides Brindley, no one had much experience with building canals or locks.

The original plan was to build a canal up the Schuylkill Valley to Norristown, then improve the river to Reading. From Reading, a canal would go to the Susquehanna, through Lebanon. This would have made it the first summit-level canal in the United States. The four-mile summit crossing between Tulpehocken and Quitipahilla would connect two river valleys. The canal would rise 192 feet over 42 miles from the Susquehanna side and then fall 311 feet over 34 miles to the Schuylkill side.

However, most of this four-mile summit crossing was built on dolomite or limestone, which are soft rocks. This meant the summit crossed ground where sinkholes were common and surface water was scarce. This made it very difficult to design and operate a water transportation system.

The 1794 engineering plan had a major flaw: there wasn't enough water for the summit crossing. The company's successor, the Union Canal, had to choose between "puddling" (packing clay to seal the canal) or "planking" (lining the canal with wood). They chose planking, which needed almost 2 million board-feet of lumber to seal the crossing. Even with two reservoirs at the summit, the Union Canal needed pumps to bring water from nearby creeks. Two of these pumps needed Cornish steam engines, a technology available in 1828 but not in 1791. By 1885, the Union Canal failed due to railroad competition, poor planning, and the difficult geology of Lebanon County. If the Schuylkill and Susquehanna Navigation Company had finished its canal in the 1790s, it likely would have faced the same problems.

James Brindley, Canal Engineer (1791-1792)

While the company was forming in 1791, the Society asked Brindley to re-evaluate the summit crossing between Lebanon, Pennsylvania and Myerstown, Pennsylvania. Brindley was to map the area and make sure there was enough water to operate the locks on both sides of the summit. He also had to estimate the land and water needed. Brindley finished his work that summer and found enough water.

The Navigation company hired Brindley in April 1792 as their canal engineer. In May, the company directors and Brindley toured the summit crossing. The route would follow Swatara Creek upstream, then Quittapahilla Creek through Lebanon, and then cross land to Tulpehocken Creek down to Reading. The summit route was set between Kuchner's dam on the Quittapahilla and Loy's springs on the Tulpehocken.

In August 1792, the company approved Brindley's plan for the summit. It would be a 25-foot deep cut, 30 feet wide at the bottom, with 4 feet of water. In October 1792, the company bought a 100-foot wide strip of land for the canal. Construction began, but local residents were not happy. They didn't like the rich Philadelphians cutting up their farms. They protested the company taking their land to build a straight canal instead of following natural paths.

William Weston, Canal Engineer (1792-1794)

While Brindley was working, the company looked for a more experienced British engineer. They hired William Weston, who was 29 years old and building canals in Ireland. Weston brought with him one of the first advanced leveling instruments used in America.

Soon after Weston arrived, the company tried to change his contract to have him work for 12 months instead of 7, offering more money. They also wanted him to work in Pennsylvania, New Jersey, New York, and Delaware.

Even though the company started work on the summit, they were still unsure in September 1792 whether to stick with their original idea of improving rivers or to build a system with locks. They also had two possible routes across the summit.

Building the Canal (1792-1794)

The company was working on several construction projects at a time when skilled workers were hard to find and expensive. To control costs, they tried to make agreements with other projects to limit wages. In October 1792, the company decided to work with the Delaware & Schuylkill Canal and the Philadelphia & Lancaster Turnpike Road. They planned to send someone to New England to hire workers together.

The next month, the company told its superintendent to limit wages to 70 cents a day, with the company providing tools. They also agreed with other companies to keep wages low. In November 1792, several companies met and agreed to cooperate. They hired Isaac Roberdeau to recruit workers and oxen. They also agreed not to raise wages by competing for workers. They planned to bring in 400 workers for each main canal, 150 for the Conewago Canal, and 200 for the turnpike. They also agreed to sell supplies to the workers at cost. The workforce was ready to start construction on March 10, 1793.

By January 1793, 80 to 100 men were working, and about half a mile of canal was dug. Brindley's design for the summit crossing assumed they would dig through earth. But they hit rock at a depth of 9 feet. The next month, about 400 men were working on the Tulpehocken Creek side of the summit. Engineer Weston reviewed Brindley's plans and changed the design. He made the canal narrower (20 feet instead of 30) but deeper (6 feet of water instead of 4), making it act as a reservoir.

By March 1793, the company had run out of money and owed $56,000 (about $1.5 million in 2018 dollars). In April, the Conewago Canal became a separate company. That same month, the company told Weston to focus on the Tulpehocken side of the summit and find more water sources.

During this time, the company tried to take more land on the Tulpehocken side. But they met resistance from local landowners, who were armed with clubs and refused to let them on their land. Construction slowed down, and in the summer of 1793, the superintendent resigned. The company got a small loan to keep going. That summer, a severe yellow fever epidemic hit Philadelphia. The company closed its offices, which made it impossible to raise more money for construction.

The Myerstown Riots of Christmas 1793

The "Myerstown Riots" happened in Myerstown, Pennsylvania, in Lebanon County. A group of young men from the town crashed a party of canal workers and started a fight. The canal workers then broke into houses looking for them. German residents had long opposed the canal because the company was taking their land, and fights between German residents and Scots-Irish or Irish canal workers were common. The riots continued for several days. A mob of over 100 canal workers, armed with clubs and led by an overseer with pistols, marched on Myerstown. They intimidated townspeople and beat young men they suspected of starting the brawl.

Washington's 1794 Expedition

In 1794, as part of the government's response to the Whiskey Rebellion, George Washington led troops in the field. He left Philadelphia, which was the capital city at the time, on September 30. On October 2, 1794, Washington left Reading to "view the canal from Myerstown towards Lebanon." Another officer noted that by then, ten miles of canal had been dug and five locks built.

Work Stops on the Canal (1794-1796)

By the end of 1793, Weston reported that lawsuits and jury awards for land had slowed the work. While Weston had over 400 men working that summer, most had left by the end of the year. The remaining workers were put on the towpath. Weston had completed 4.25 miles of the canal through the narrowest part of the summit. However, he had to make the summit cut narrow enough for only one boat at a time. Crucially, Weston also had to line both sides of the canal with dry stone walls to reduce water leakage.

Going into 1794, Weston estimated he needed $231,000 (about $4.9 million in 2018 dollars) for the year's work, meaning the company needed to raise another $120,000. The company couldn't raise the money. On May 3, 1794, it reported that its funds were gone.

However, the company kept trying to raise money. In December 1794, Chief Engineer Weston gave his last report on the Schuylkill & Susquehanna Navigation project. He noted that they had spent £8,526 on 4 miles of canal, five completed locks, and two bridges. Funds were still not enough. By the end of 1794, the company made its final payroll and told Weston he would only work for the Delaware and Schuylkill Canal company.

The company's efforts to get more money failed. Finally, in April 1795, the company ordered Weston to sell their equipment and send bricks made for the locks to another canal project. The canal works were abandoned and never used. In the spring of 1796, the company ordered all the bricks to be sold, officially ending the project.

Supporting Other Canal Projects (1795-1796)

As the navigation company ran out of money by early 1795, they ended Weston's contract with them in May. Weston still worked for the Delaware and Schuylkill Canal company. By spring 1796, Weston reported that six miles of canal had been completed, but work stopped due to lack of funds. The Delaware and Schuylkill Canal company also ended Weston's contract that spring. Weston then went to work for the Western Inland Lock Navigation Company in New York for four years. During this time, Benjamin Wright, who later became the Chief Engineer of the Erie Canal, worked under Weston.

Merger and New Start as the Union Canal Company (1800-1811)

Even though construction stopped, the company managed to keep its property and water rights. In 1802, they avoided losing their property by selling off extra land. The company's original charter was set to expire in 1801, but it was extended to 1820 in 1806.

In 1807, Charles Gottfried Paleske was elected to the company's Board of Directors. He and others walked the route of the Schuylkill & Susquehanna Navigation Company. They found the work in good condition, including five locks, but bridges were decayed. In 1808, Paleske became President. In 1809, the company's directors planned to merge with the Delaware and Schuylkill Canal company.

In July 1811, the two companies officially merged to form the Union Canal Company. Paleske was its first president. The new company was allowed to extend the canal to Lake Erie and build turnpikes. It was also given a monopoly on lotteries in Pennsylvania until it raised $400,000.

Legacy and Impact

George Washington once observed that people tend to focus on the direction their rivers flow. He believed that connecting the East and West parts of the country with artificial waterways was crucial for the nation's unity and economy. At that time, improving riverbeds and building canals was the only way to create trade links.

Even the best roads couldn't serve communities hundreds of miles apart well. It cost about 13 cents to transport one ton of goods for one mile on a road. But it cost less than one-twenty-fifth of that amount to transport goods by water. It was often cheaper to bring a ton of goods from Europe (3,000 miles away) for about $9 than to carry the same goods 30 miles on a good road. For example, iron forges in Lancaster County before the Revolution only supplied local needs because it cost more than twice as much to transport their products 75 miles by wagon than it did to ship goods across the Atlantic Ocean.

The Golden Link

During this period (1789-1820), Philadelphia's business leaders focused on central Pennsylvania and its large Susquehanna watershed. However, much of Pennsylvania's trade went out of the state, away from Philadelphia, to its rivals: Baltimore (at the end of the Susquehanna system) and Albany (in New York). It was estimated that half of the goods shipped down the Susquehanna River ended up in Baltimore, not Philadelphia.

People like Samuel Breck and William Duane argued that connecting the Schuylkill and Susquehanna rivers would solve these problems. It would ensure Philadelphia's trade would grow. Breck believed that improving the Schuylkill River was important, but he called the connection between Reading and Middletown the "golden link." He said, "If we make a good channel using the waters of the Tulpehocken... and those of the Swatara... and thus reach that great river, we are (forever) safe, as a town." The success of this whole plan depended on this "golden link" built by the Schuylkill and Susquehanna Navigation Company at Lebanon, Pennsylvania.

A Big Failure

The State's response to these ideas varied. In 1791, it passed some laws and provided a little money for river navigation, turnpike roads, and private canal companies. However, as shown by the Lebanon summit canal project, river improvements often didn't work well in Pennsylvania.

Turnpike roads, like the Philadelphia and Lancaster Turnpike Road Company of 1792, were more successful, though expensive. But private canal companies, even with state help, were a "dismal failure." Nothing significant was achieved in canals until about 1821. The problems with these early canal companies led the state to take over canal building later.

Despite the excitement at the time, the Chief Engineer for the Erie Canal later wrote in 1905 that Pennsylvania might have succeeded in building its canal if it weren't for the Erie Canal. The Erie Canal helped New York State gain commercial importance. The failure of the Schuylkill and Susquehanna Navigation Company meant that Philadelphia lost its early lead in water transportation by 1795. Even though Philadelphia's trade was much larger than New York's in 1796, by 1825, after the Erie Canal opened, Philadelphia's trade was much smaller.

Philadelphia as the American Metropolis

New York's rise to become the most important American city was not guaranteed. At the time of the American Revolution, Philadelphia was the leading city. People expected it to become even more important as the nation grew. Instead, Philadelphia fell to second place. By 1807, New York was the recognized business capital. By 1837, it was clearly the biggest city in America. Philadelphia's failure to build the "golden link" canal 30 years before New York opened the Erie Canal was a major reason for this decline.

Images for kids

| Janet Taylor Pickett |

| Synthia Saint James |

| Howardena Pindell |

| Faith Ringgold |