Second Grinnell expedition facts for kids

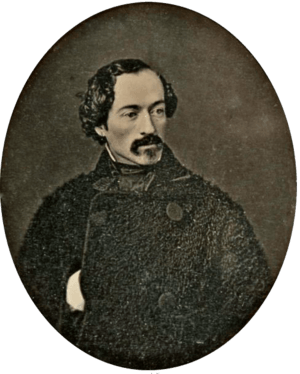

The Second Grinnell Expedition was an American adventure from 1853 to 1855. It was paid for by Henry Grinnell to find out what happened to Franklin's lost expedition, a group of explorers who had disappeared while searching for a Northwest Passage. This new expedition was led by Elisha Kent Kane. His team explored areas northwest of Greenland, which are now known as Grinnell Land.

Even though they didn't find Sir John Franklin, the expedition achieved amazing things. They traveled farther north than anyone before, mapped about 960 miles (1,540 km) of coastline that no one had seen, and discovered the long-talked-about open Polar Sea. Kane also gathered important information about geography, weather, and Earth's magnetic field. In 1855, they had to leave their ship, the brig Advance, stuck in the ice. Three crew members were lost, but the incredible journey of the survivors became a famous story of survival in the Arctic.

Contents

Getting Ready for the Arctic

A retired merchant named Henry Grinnell became very interested in the missing Franklin expedition. Franklin had left in 1847 to find a Northwest Passage through the Arctic islands. Lady Jane Franklin, John Franklin's wife, encouraged Grinnell. Since the government wouldn't give money, Grinnell paid for a first trip in May 1850. This expedition, led by Lieutenant Edwin De Haven, used two ships: the USS Rescue and the USS Advance. Elisha Kent Kane was the main doctor on the Advance.

The first trip didn't solve the mystery. However, working with another expedition, they found Franklin's first winter camp and three graves on Beechey Island on August 24, 1850. Grinnell didn't give up! He prepared the 144-ton ship Advance for a second journey. Dr. Kane would lead this trip for the U.S. Navy. Their goal was to search for Franklin north of Beechey Island and find the open Polar Sea that was thought to exist in summer. With help from the Geographical Society of New York, the Smithsonian Institution, the American Philosophical Society, and $10,000 from George Peabody, the expedition left New York on May 30, 1853. They had a small crew, some supplies, trade items, and science tools.

Journey and Discoveries

By July 1853, the Advance reached Danish settlements in Greenland, like Fiskenaesset and Upernavik. There, they got more supplies, an interpreter named Karl Petersen, and a 19-year-old Kalaallit hunter and dog handler named Hans Hendrik. In early August, they sailed through the sea ice in Melville Bay by tying their ship to icebergs moving north. Kane left a pile of stones on Littleton Island to mark their path. By August 23, they had reached 78° 41′ North, one of the farthest north any ship had gone in the Baffin Bay area. They made several sled trips into Greenland to set up supply spots and make observations, reaching 78° 52′ North. On September 10, the Advance settled for winter in Rensselaer Harbor.

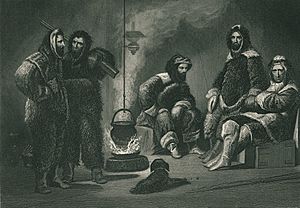

During the dark winter, they built a small stone observatory on land. They also made several trips by dog sled to set up more supply spots and map the area, going as far as 79° 50′ North. The crew kept busy by putting on plays, publishing an Arctic newspaper called The Ice-Blink, and taking care of the sled dogs. By March, the outside temperature was around −46 °F (−43 °C), and it had dropped to −67 °F (−55 °C) on February 5, 1854. By the end of winter, most of the sled dogs had died from a sickness like lockjaw, and many crew members showed signs of scurvy, a disease caused by lack of Vitamin C.

On March 20, a group went out to set up a supply depot. On March 30, three of them (Sonntag, Ohlsen, and Petersen) returned to the Advance very weak. They needed immediate help for the other four: Brooks, Baker, Wilson, and Pierre. Ohlsen tried to guide the rescue team back, but Hans Hendrik eventually found the frozen men's sled trail after walking for 21 hours straight. Despite being tired, facing strong winds, and temperatures of −55 °F (−48 °C), the rescue party brought everyone back to the Advance. However, Jefferson Baker later died. The rescue team had been out for 72 hours and traveled almost 90 miles (140 km).

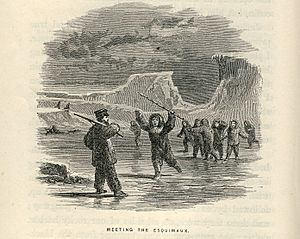

On April 26, after trading with some Inuit hunters, teams led by Kane, McGary, and Godfrey set out with fresh dogs for the Humboldt Glacier. They hoped to reach the American side using their earlier supply spots. Once there, they planned to search the ice for possible water channels and make observations. They crossed Marshall Bay, but scurvy and bad travel conditions slowed them down. On May 4, they found that polar bears had ruined their supply depots. When Kane became ill, the group turned back, reaching the ship on May 14. Peter Schubert died on the way back, and his body was placed in the observatory with Baker's.

While others recovered, Dr. Hayes went on a dogsled trip north to Cape Sabine on May 20, as temperatures rose above freezing. He returned on June 1 after mapping the Greenland coast. On June 3, McGary and Morton went on coastal trips along the Kennedy Channel, reaching 81 degrees North at Morris Bay. They returned later that month, having faced polar bears, ruined supply caches, and melting ice. As temperatures kept rising, the remaining crew made short observation trips. They noticed birds migrating and used the returning plants to help cure their ongoing scurvy.

By early July 1854, Kane thought about spending another winter trapped in the ice, even though they didn't have enough supplies for another year. Leaving the Advance was seen as a dishonorable choice. Kane and five men tried to reach Beechey Island in a 23 feet (7.0 m) whaleboat. Kane knew this island from the first Grinnell expedition, where Franklin's 1845 winter camp was found. Kane hoped to meet Sir Edward Belcher's rescue expedition and get supplies there.

A strong storm and thick ice stopped them. They sailed and pulled the boat, but on July 31, they were stopped by ice just 10 miles (16 km) from Cape Parry. They had to return to the ice-locked Advance. Blasting the ice briefly freed the ship on August 12, but it quickly got stuck again in an ice floe. The crew hoped the ice would break up, but their supplies were running low. Expecting the worst, they hid important documents at the observatory, marking the spot with a large stone painted "Advance, A.D. 1853–1854."

Trapped in the Ice

On August 23, Kane knew the Advance would not break free. Eight of the seventeen survivors decided to stay with the ship and hope to survive the winter. The other eight left on August 28 for Upernavik, though one returned to the ship the next day. Those who stayed with Kane on the Advance quickly began preparing for winter. These included Brooks, McGary, Wilson, Goodfellow, Morton, Ohlsen, Hickey, and the Inuk, Hans Christian.

Learning from the Inuit, Kane and his men spent early September insulating the ship's deck with moss and turf, and doing the same below deck. They removed parts of the outer decks, getting over seven tons of firewood for heat and melting snow. These preparations kept the temperature below decks between 36 and 45 °F (2 and 7 °C), even in the coldest months. They made an agreement with nearby Inuit to trade for meat and share the ship as shelter. This helped them hunt together and strengthened their bond. Local exploration and hunting continued into early October, when the Inuit quietly left.

Before full darkness arrived, they saved their remaining bread, beef, and pork. They added to their winter food with occasional polar bear, fox, hares, and even rats, which they shot on the ship with bows and arrows to pass the time. Kane also tried making root beer from willow shoots. In mid-October, Morton and Hans went by sled to find the Inuit, hoping to find hunting grounds. They reached a small seasonal settlement near Hartstene Bay and successfully hunted walrus with their hosts. They returned to the ship with meat on the 21st. The ship was regularly lifted above the ice with chains to prevent it from being crushed by the growing ice. Scurvy returned, and everyone felt down. During these times, they often thought about what happened to Franklin's group.

On December 7, a group of Inuit arrived, bringing two men (Bonsall and Peterson) from the group that had left on August 28. They reported that their situation was terrible, and the rest of their group was starving about 200 miles (320 km) away. Precious rescue supplies were sent to them, and with the help of the Inuit, the rest of the Advance crew returned on the 12th, very weak. The Inuit later returned and enjoyed Kane's hospitality.

On December 23, a lamp-fire started in a storage room and set the dry wood and moss walls on fire. The fire was put out with animal skins and water, but it was a tough test for the crew. Kane soon left to get walrus meat from the Inuit near Cape Alexander to help the worst cases of scurvy. This was a 22-hour journey in temperatures of −54 °F (−48 °C). Their dogs failed, forcing them back to the ship without getting the meat. The crew was now only warmed by their lamps. On January 22, Kane and Hans set out again, lightly equipped, ready to use their dogs to survive their 93 miles (150 km) journey.

A storm and snow kept them stuck in an abandoned Inuit home for two days. With their health, supplies, and dogs failing, they were forced to return to the ship empty-handed on January 30, 1855. By this time, almost all the crew were sick in bed with advanced scurvy, even though the temperatures were unusually warmer, above −20 °F (−29 °C). On February 3, Peterson and Hans went to find the local Inuit after Kane spotted a trail. Three days later, they returned, weak and turned back by increasing snow and their own failing strength.

In the following days, the crew survived on occasional hares, caribou, and 'beer' brewed from flax-seed. They kept warm by burning hemp cable and gear. The health of the sickest continued to get worse despite the sun slowly returning, as temperatures stayed between −40 and −50 °F (−40 and −46 °C). Hans went to find meat from the nearby Eskimos, but they were also facing a food shortage. He helped them on a successful walrus hunt and returned on March 10 to the ship with his share of the meat, which helped the sick. During this time, Hans wanted to visit the Inuit village of Peteravik on foot, which Kane allowed. Hans had planned to return but was convinced to stay with his hosts, eventually moving south with them.

In late March, William Godfrey left the group. He returned to the Advance on April 2 but ran away again. Kane recaptured him at an Inuit village on April 18 without trouble.

The Great Escape

With some improvement in health, they began planning their escape to open water across the ice. The ice showed no sign of releasing the Advance. Working and hunting with the local Inuit provided walrus and bear meat, helping the crew recover. They used the few remaining ship timbers as runners for two 17.5-foot-long (5.3 m) sledges for their 26-foot-long (7.9 m) whaleboats. They made bolts from curtain rods. Only four dogs remained, the rest having died, though some were borrowed from the local Inuit. By early May, all but four of the crew were fairly healthy again. Kane and Morton made one last search towards the far coast of the Kane Basin, but found no sign of Franklin's group. The search was officially over, and everyone focused on escaping.

All efforts went into making equipment and clothing for the escape. As planning continued, May 17 was chosen as the day to leave. A basic supply of food would be carried on the sledges, added to by hunting and limited dogsled trips back to the ship. The two dried-out cypress whaleboats, named Faith and Hope, were strengthened with oak where possible, fitted with masts that could be folded down, and covered with stretched canvas. A third boat, Red Eric, was brought along for fuel. Provisions, ammunition, cooking gear, and a few valuable scientific tools were packed inside these. Each man was allowed eight pounds of personal items.

On May 17, they began their 1,300 miles (2,100 km) journey. The recently sick crew members pulled the sledges themselves. They only gained two miles (3.2 km) the first day, but they slowly got better at it, resting on the Advance while it was still nearby. On May 20, 1855, when they finally left the Advance for good, the crew gathered on the empty ship, said a prayer, and quietly packed away a portrait of Sir John Franklin. The figurehead, "Augusta," was removed and loaded onto the sledges – to be used for wood if not for honor. Kane spoke to the crew about their achievements and the challenge ahead. They signed a statement agreeing to abandon the ship:

The undersigned, being convinced of the impossibility of the liberation of the brig, and equally convinced of the impossibility of remaining in the ice a third winter, do fervently concur with the commander in his attempt to reach the South by means of boats.

Knowing the trials and hardships which are before us, and feeling the necessity of union, harmony, and discipline, we have determined to abide faithfully by the expedition and our sick comrades, and to do all that we can, as true men, to advance the objects in view.

Fixed to a stanchion near the gangway, Kane left a note for anyone who might later find the ship. It ended with these words:

I regard the abandonment of the brig as inevitable. We have by actual inspection but thirty-six days' provisions, and a careful survey shows that we cannot cut more firewood without rendering our craft unseaworthy. A third winter would force us, as the only means of escaping starvation, to resort to Esquimaux habits and give up all hope of remaining by the vessel and her resources. It would therefore in no manner advance the search after Sir John Franklin.

Under any circumstances, to remain longer would be destructive to those of our little party who have already suffered from the extreme severity of the climate and its tendencies to disease. Scurvy has enfeebled more or less every man in the expedition, and an anomalous spasmodic disorder, allied to tetanus, has cost us the life of two of our most prized comrades.

I hope, speaking on the part of my companions and myself, that we have done all that we ought to do to prove our tenacity of purpose and devotion to the cause which we have undertaken. This attempt to escape by crossing the southern ice on sledges is regarded by me as an imperative duty, – the only means of saving ourselves and preserving the laboriously-earned results of the expedition.—Advance, Rensselaer Bay, May 20, 1855

The twelve healthy crewmen took turns pulling each of the three sledges. They focused on a daily routine and discipline, with Hayes and Sonntag recording their progress. An abandoned Inuit home at Annoatok served as a temporary hospital while the men pulling the sledges stayed nearby. Additional supplies had been hidden close by. Kane transported supplies and sick crew members by dogsled and even returned to the ship to get more provisions and bake fresh bread on the stove, using books as fuel. They stopped based on the men's condition, and progress was slow but steady, despite pulling for 14 hours a day. They often used axes to cut through ice hills or to make ramps between layers of ice. Their health worsened under the strain of moving the heavy sledges across the ice, and scurvy symptoms increased, requiring more food. Kane's further trading with the Inuit improved their food supply as temperatures warmed, but the provisions packed on the boats were saved at all costs.

Warmer temperatures and melting ice added to the dangers. The sledges and boats sometimes broke through the ice, barely escaping being lost. In one such incident on June 2, Ohlsen saved the Hope, but he broke through the ice himself, hurting a blood vessel. Although rescued, his condition was serious. While trying to reach the Inuit settlement of Etah near Littleton Island, strong storms forced Kane's dogsled party to dig into the snow before retreating. A second attempt brought meat, blubber, and fresh dogs from the generous Inuit, whose regular help was priceless. Refreshed, Kane brought the four sick men from their shelter at Annoatok, one by one. On June 6, after raising sails on the boat-sledges, the men used steady winds to help them travel eight miles (13 km) across the ice towards their supply cache at Littleton Island.

Hans was still missing, having not returned to the group since leaving in April, though he had planned to meet them at the village in Etah. From nearby villagers, Kane learned that Hans had married a maiden from Peteravik and then gone south to Qeqertarsuatsiaat to start a new life. Kane's group greatly missed him.

The untouched supply cache at Littleton Island was found on July 12. While on Littleton, Ohlsen finally died from his illness and was buried in a natural crack in the rocks, with a cape named after him nearby. After crossing 80 miles (130 km) of ice, open water was seen six miles (9.7 km) to the southwest, and the final push was planned.

As they continued their march, many Inuit came to help them, assisting with the pulling and offering fresh meat from the now plentiful auks. They reached the open water on June 16, 1855. After saying goodbye to the gathered Inuit and giving them gifts, including most of the remaining dogs, Kane and the survivors launched their three boats on June 19, after being delayed by another storm.

The dried, weather-beaten wooden boats began leaking, and the Red Eric was almost lost as they headed for the protection of the ice inlets. They soon took shelter on Hakluyt Island and repaired the boats. They set out again on June 22, hopping from island to island to Northumberland Island, then camping at Cape Parry. They hunted along the way, melting snow from icebergs for water. Because of the harsh winter, they soon met unbroken ice to the south. As their hope faded, a storm rose and broke the ice floe, and they returned to the water among the loose ice. Landing on an ice shelf as the storm returned, they found they were in the middle of an eider bird nesting area, and the birds and raw eggs helped them regain their strength. They set out again on July 3, staying close to the shore, but chains of icebergs blocked their way, slowing them down. They kept going, and by July 11, they neared Cape Dudley Digges.

The boats continued to fall apart. Landing near a glacier, they found many birds and plants, which added to their diet until they set off again on July 18, reaching Cape York on the 21st. Seeing open water channels, they extended their fuel supply by breaking up the Red Eric and gathering what they could. When the channels closed, the boats were again pulled across the ice by hand. Food was reduced as they headed for Cape Shackleton through fog and ice, and the crew's health worsened again. On the ice floes, they finally caught a seal, and their strength returned. More seals ended their hunger for good.

By August 1, they had reached open waters where whaling ships operated. Two days later, they found English-speaking people. Kane finally reached Upernavik on August 8, 1855, after being in the open for 84 days.

What Happened Next

On September 6, the crew got a ride on the Danish ship Mariana to the Shetland Islands, bringing the Faith boat as a reminder of their tough journey. Near Lively, they met the Hartstene expedition, which had set out to find Dr. Kane that previous May. Kane's brother, Dr. John K. Kane, along with Lieutenant Hartstene, had learned Kane's route from the local Inuit and got within 40 miles (64 km) of the abandoned ship Advance. Both expeditions returned to New York on October 11, 1855.

Kane finished writing about his voyage, but his health was already getting worse. He said, "The book, poor as it is, has been my coffin." He was joined by his family and William Morton in Cuba, where he died on February 16, 1857. His life was publicly celebrated and many people mourned his passing.

The expedition didn't find much about Franklin's fate and was Grinnell's last American effort in this search. Surgeon Hayes would launch his own Arctic expedition in 1860, which included Sonntag as an astronomer and Hans Christian. This trip would sadly claim Sonntag's life. The British Navy continued searching for Franklin until 1880.

Crew of the Advance

- Henry Brooks, first officer

- Isaac Israel Hayes, surgeon

- August Sonntag, astronomer

- John Wall Wilson

- James McGary

- George Riley

- William Morton

- Christian Ohlsen

- Henry Goodfellow

- Amos Bonsall

- George Stephenson

- George Whipple

- William Godfrey

- John Blake

- Jefferson Baker

- Peter Schubert

- Thomas Hickey

- Hans Hendrik

- Karl Petersen

Expedition's Lasting Impact

The Kane Basin, a large body of water, is named after Kane. It also includes the glacier Kane named after Alexander von Humboldt.

Kane provided the first detailed information about the Etah Inuit, who are the northernmost people on Earth. Even though his collected samples were lost, his notes gave a lot of information about the plants and animals, as well as the magnetic, weather, tide, and glacier features of this extreme part of western Greenland.

Kane's group survived better by learning and using Inuit techniques. These included using dogsleds, hunting, building shelters, and forming a close relationship with the local people. These steps might have helped the Franklin expedition, who likely stuck to their European ways throughout their ordeal. Kane said:

When trouble came to us and to them, and we bent ourselves to their habits, – when we looked to them to procure us fresh meat, and they found at our poor Oomiak-soak shelter and protection during their wild bear-hunts, – then we were so blended in our interests as well as modes of life that every trace of enmity wore away.

—Elisha Kane, The United States Grinnell Expedition in Search of Sir John Franklin

Franklin had faced several Inuit attacks during his 1826 overland expedition. This likely influenced his later decisions about working with local people.

Kane's ability to regularly get fresh meat, mostly from summer hunts with the Inuit, prevented the worst symptoms of scurvy. Franklin's expedition relied on canned foods, which were prepared quickly and had high lead levels due to poor soldering. Lead poisoning was a major factor against their survival. While Kane's smaller group made hunting easier, this difference was key to how each expedition ended.

| Jewel Prestage |

| Ella Baker |

| Fannie Lou Hamer |