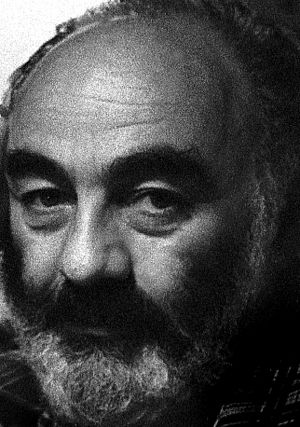

Sergei Parajanov facts for kids

Sergei Parajanov (born January 9, 1924 – died July 20, 1990) was an Armenian filmmaker. Many film experts believe Parajanov was one of the greatest and most important directors in movie history.

He created his own unique movie style. This style was very different from "socialist realism," which was the only art style allowed in the Soviet Union at the time. Because of his unique art and his personal life, Soviet officials often caused him trouble. They even put him in prison and tried to stop his films from being seen.

Even with these challenges, Parajanov was named one of the "20 Film Directors of the Future" by a film festival in Rotterdam. His movies were also listed among the best films ever made by the British Film Institute.

Parajanov started making films professionally in 1954. However, he later said that all the films he made before 1965 were not good. After directing Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors in 1965, he became famous around the world. But this also made him a target for attacks from the Soviet Union.

Many of his film projects from 1965 to 1973 were stopped or banned by Soviet film groups. He was arrested in late 1973 on false charges and stayed in prison until 1977. Many artists asked for him to be released. Even after he was set free, he was not allowed to work easily in Soviet cinema. It was only in the mid-1980s, when the political situation became more relaxed, that he could direct again. He needed help from friends, like the Georgian actor Dodo Abashidze, to get his last films approved.

His health became very weak after spending four years in labor camps and nine months in prison. Parajanov died of cancer in 1990. This was a time when, after almost 20 years of being suppressed, his films were finally being shown at international film festivals. In 1988, he said, "Everyone knows that I have three Motherlands. I was born in Georgia, worked in Ukraine and I'm going to die in Armenia." Parajanov is buried at Komitas Pantheon in Yerevan.

Parajanov's films won awards at many festivals, including Mar del Plata, Istanbul, and Rotterdam. A big show of his films happened in the UK in 2010 at BFI Southbank.

Contents

Early Life and Film Studies

Sergei Parajanov was born with the name Sarkis Hovsepi Parajaniants in Tbilisi, Georgia. His parents, Iosif Paradjanov and Siranush Bejanova, were Armenian and very artistic. A historical document at the Sergei Parajanov Museum in Yerevan confirms his family name. He was surrounded by art from a young age.

In 1945, he went to Moscow and joined the directing program at VGIK. This is one of the oldest and most respected film schools in Europe. He learned from famous directors like Igor Savchenko and Oleksandr Dovzhenko.

In 1948, he faced unfair accusations in Tbilisi and was sentenced to five years in prison. However, he was released after only three months. His friends and family said that these charges were false. They believed the punishment was a way to get back at him for his independent ideas.

In 1950, Parajanov married his first wife, Nigyar Kerimova, in Moscow. She was from a Muslim Tatar family and changed to Eastern Orthodox Christianity to marry him. After she passed away, Parajanov moved from Russia to Kyiv, Ukraine. There, he made several documentaries and narrative films. He learned to speak Ukrainian fluently. In 1956, he married his second wife, Svitlana Ivanivna Shcherbatiuk. They had a son named Suren in 1958. The couple later divorced, and Svitlana and Suren moved to Kyiv.

Breaking Away from Soviet Rules

Andrey Tarkovsky's first film, Ivan's Childhood, greatly inspired Parajanov to find his own style as a filmmaker. Later, they became close friends and influenced each other. Another director who inspired Parajanov was the Italian filmmaker Pier Paolo Pasolini. Parajanov called him "like a God" and praised his "majestic style."

In 1965, Parajanov stopped following "socialist realism." This was a strict art style that the Soviet government wanted all artists to use. He then directed the poetic film Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors. This was his first film where he had full creative control. It won many international awards and was even liked by Soviet officials at first. They praised it for showing the "poetic quality and philosophical depth" of the story it was based on. They also allowed the film to keep its original Ukrainian language, which was unusual at the time.

Soon after, Parajanov moved to Armenia, the homeland of his ancestors. In 1969, he started working on Sayat Nova. Many people think this film is his greatest work, even though it was made with a very small budget and in difficult conditions. Soviet censors stopped Sayat Nova because they thought its content was too controversial. Parajanov then re-edited the film and renamed it The Color of Pomegranates.

Actor Alexei Korotyukov once said, "Paradjanov made films not about how things are, but how they would have been had he been God." Film critic Mikhail Vartanov wrote in 1969 that "Besides the film language suggested by Griffith and Eisenstein, the world cinema has not discovered anything revolutionarily new until The Color of Pomegranates ...".

Imprisonment and Later Films

By December 1973, Soviet officials were very suspicious of Parajanov's independent ideas and lifestyle. They sentenced him to five years in a strict prison camp. Just three days before his sentencing, Andrei Tarkovsky wrote a letter to the Communist Party of Ukraine. He said that Parajanov's two films, Shadows of Our Forgotten Ancestors and The Colour of Pomegranates, had a huge impact on cinema in Ukraine, the Soviet Union, and the world. Tarkovsky added that "Artistically, there are few people in the entire world who could replace Paradjanov."

Many artists, actors, filmmakers, and activists protested to help Parajanov. They asked for him to be released right away. Famous people like Robert De Niro, Francis Ford Coppola, Martin Scorsese, Jean-Luc Godard, François Truffaut, Luis Buñuel, Federico Fellini, and Andrei Tarkovsky were among them.

Parajanov spent four years of his five-year sentence in prison. He later said that his early release was thanks to the efforts of the French poet Louis Aragon, the Russian poet Elsa Triolet, and the American writer John Updike. His release was approved by Leonid Brezhnev, the leader of the Soviet Union. This happened after Brezhnev met Aragon and Triolet and Aragon asked for Parajanov's freedom. He was released by December 1977.

While in prison, Parajanov created many small doll-like sculptures and about 800 drawings and collages. Many of these are now shown in Yerevan at the Sergei Parajanov Museum. This museum opened in 1991, a year after Parajanov's death. It has over 200 of his works and furniture from his home in Tbilisi. Prison guards often tried to stop his creative work, but they became less cruel after Moscow confirmed that "the director is very talented."

After he returned from prison to Tbilisi, Soviet censors watched him closely. This stopped him from making films, so he focused on other art forms he had started in prison. He made very detailed collages, abstract drawings, and even sewed dolls and unique suits.

In February 1982, Parajanov was put in prison again on charges of bribery. This happened when he returned to Moscow for a play. Despite another harsh sentence, he was freed in less than a year, but his health was much weaker.

In 1985, the Soviet Union began to relax its rules, which allowed Parajanov to return to filmmaking. With help from Georgian thinkers, he made the award-winning film The Legend of Suram Fortress. This was his first film since Sayat Nova, fifteen years earlier. In 1988, Parajanov made another award-winning film, Ashik Kerib. This film is about a traveling singer and is set in Azerbaijani culture. Parajanov dedicated this film to his close friend Andrei Tarkovsky and "to all the children of the world."

Death

Parajanov then tried to finish his last film project. He died of cancer in Yerevan, Armenia, on July 20, 1990, at the age of 66. His final work, The Confession, was left unfinished. The original film footage survives in Parajanov: The Last Spring, a film made by his close friend Mikhail Vartanov in 1992. Many famous filmmakers and artists, including Federico Fellini, Francis Ford Coppola, and Martin Scorsese, publicly mourned his death. They sent a message saying, "The world of cinema has lost a magician. Parajanov’s fantasy will forever fascinate and bring joy to the people of the world…”.

Influences and Legacy

Even though Parajanov studied film at VGIK, he found his unique artistic style after seeing Soviet director Andrei Tarkovsky's dreamlike first film Ivan's Childhood.

Tarkovsky himself greatly admired Parajanov. In his film "Voyage in Time", Tarkovsky said, "Always with huge gratitude and pleasure I remember the films of Sergei Parajanov which I love very much. His way of thinking, his paradoxical, poetical... ability to love the beauty and the ability to be absolutely free within his own vision." Tarkovsky also stated that Parajanov was one of his favorite filmmakers.

Italian filmmaker Michelangelo Antonioni said that "The Color of Pomegranates by Parajanov, in my opinion one of the best contemporary film directors, strikes with its perfection of beauty.” American filmmaker Francis Ford Coppola also admired Parajanov. French film director Jean-Luc Godard stated that "In the temple of cinema, there are images, light, and reality. Sergei Parajanov was the master of that temple."

Even though many people admired his art, his unique vision did not have many direct followers. He reportedly said, "Whoever tries to imitate me is lost." However, directors like Theo Angelopoulos and Béla Tarr share Parajanov's idea that film should be mostly about visuals, not just telling a story.

The Parajanov-Vartanov Institute was started in Hollywood in 2010. Its goal is to study, protect, and promote the artistic works of Sergei Parajanov and Mikhail Vartanov.

Filmography

| Year | English title | Original title | Romanization | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1951 | Moldavian Tale | In Russian: Молдавская сказка In Ukrainian: Moлдавська байка |

Moldavskaya Skazka | Short film for graduation; lost |

| 1954 | Andriesh | In Russian: Андриеш | Andriesh | Co-directed; a longer version of Moldavian Tale |

| 1958 | Dumka | In Ukrainian: Думка | Dumka | Documentary film |

| 1958 | The First Lad (also known as The Top Guy) | In Russian: Первый парень In Ukrainian: Перший пapyбок |

Pervyj paren | |

| 1959 | Natalya Ushvij | In Russian: Наталия Ужвий | Natalia Uzhvij | Documentary film |

| 1960 | Golden Hands | In Russian: Золотые руки | Zolotye ruki | Documentary film |

| 1961 | Ukrainian Rhapsody | In Russian: Украинская рапсодия In Ukrainian: Укpaїнськa рaпсодія |

Ukrainskaya rapsodiya | |

| 1962 | Flower on the Stone | In Russian: Цветок на камне In Ukrainian: Квітка на камені |

Tsvetok na kamne | |

| 1965 | Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors | In Ukrainian: Тіні забутих предків | Tini zabutykh predkiv | |

| 1965 | Kyiv Frescoes | In Russian: Киевские фрески | Kievskie Freski | Banned before filming began; only 15 minutes of try-out footage remain |

| 1967 | Hakob Hovnatanian | In Armenian: Հակոբ Հովնաթանյան | Hakob Hovnatanyan | Short film about a 19th-century Armenian artist |

| 1968 | Children to Komitas | In Armenian: Երեխաներ Կոմիտասին | Yerekhaner Komitasin | Documentary for UNICEF; lost |

| 1969 | The Color of Pomegranates | In Armenian: Նռան գույնը | Nran guyne | |

| 1985 | The Legend of Suram Fortress | In Georgian: ამბავი სურამის ციხისა | Ambavi Suramis tsikhisa | |

| 1985 | Arabesques on the Pirosmani Theme | In Russian: Арабески на тему Пиросмани | Arabeski na temu Pirosmani | Short film about the Georgian painter Niko Pirosmani |

| 1988 | Ashik Kerib | In Georgian: აშიკი ქერიბი In Azerbaijani: Aşıq Qərib |

Ashiki Keribi | |

| 1989–1990 | The Confession | In Armenian: Խոստովանանք | Khostovanank | Unfinished; original film footage used in Mikhail Vartanov's Parajanov: The Last Spring |

Screenplays

Produced and Partially Produced Screenplays

- Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors (Тіні забутих предків, 1965, co-written, based on a story by Mykhailo Kotsiubynsky)

- Kyiv Frescoes (Київські фрески, 1965)

- Sayat Nova (Саят-Нова, 1969, the script for The Color of Pomegranates)

- The Confession (сповідь, 1969–1989)

- Swan Lake: The Zone (Лебедине озеро. Зона, 1989, filmed in 1990)

Unproduced Screenplays and Projects

- The Dormant Palace (Дремлющий дворец, 1969, based on Pushkin's poem The Fountain of Bakhchisaray)

- Intermezzo (1972, based on Mykhailo Kotsiubynsky's short story)

- Icarus (Икар, 1972)

- The Golden Edge (Золотой обрез, 1972)

- Ara the Beautiful (Ара Прекрасный, 1972, based on a poem about Ara the Beautiful)

- Demon (Демон, 1972, based on Lermontov's poem)

- The Miracle of Odense (Чудо в Оденсе, 1973, inspired by the life of Hans Christian Andersen)

- David of Sasun (Давид Сасунский, mid-1980s, based on an Armenian epic poem)

- The Martyrdom of Shushanik (Мученичество Шушаник, 1987, based on a Georgian historical text)

- The Treasures of Mount Ararat (Сокровища у горы Арарат)

Awards and Recognition

- There is a statue of Parajanov in Tbilisi, Georgia.

- A plaque marks his childhood home.

- The street where Parajanov grew up was renamed Parajanov Street in 2021.

- There is a museum dedicated to Parajanov in Yerevan, Armenia.

Images for kids

-

Parajanov's tombstone in Yerevan

See Also

In Spanish: Serguéi Paradzhánov para niños

In Spanish: Serguéi Paradzhánov para niños

- Art film

- Asteroid 3963 Paradzhanov

- Cinema of Armenia

- Cinema of Georgia

- Cinema of the Soviet Union

- Cinema of Ukraine

- Serhii Parajanov Museum

- List of directors associated with art film