Sesame Workshop facts for kids

|

|

| Founded | May 20, 1968 |

|---|---|

| Founders | Joan Ganz Cooney Lloyd Morrisett |

| Type | Non-profit |

| Legal status | 501(c)(3) |

| Headquarters | 1 Lincoln Plaza |

| Location |

|

|

Area served

|

Worldwide |

| Sherrie Westin | |

| Sherrie Westin | |

| Subsidiaries | Sesame Street Inc. Sesame Workshop Communications Inc. Sesame Workshop Initiatives (India) Private Limited Sesame Street Brand Management and Services (Shanghai) |

|

Revenue (2014)

|

US$104,728,963 |

| Expenses (2014) | US$111,255,622 |

|

Employees (2013)

|

813 |

|

Formerly called

|

Children's Television Workshop (CTW) (1968–2000) |

Sesame Workshop (SW), originally known as the Children's Television Workshop (CTW), is an American nonprofit organization. This means it's a company that doesn't aim to make money for owners. Instead, it uses its earnings to support its mission. It's also a television production company. Sesame Workshop is famous for creating many educational children's shows. Its first and most well-known show is Sesame Street. These shows have been seen by kids all over the world.

Joan Ganz Cooney and Lloyd Morrisett came up with the idea for an organization to make the Sesame Street TV series. They spent two years, from 1966 to 1968, doing research, planning, and raising money. Joan Ganz Cooney became the Workshop's first executive director. Her appointment was called "one of the most important television developments of the decade."

Sesame Street first aired in the United States on November 10, 1969, on National Educational Television (NET). It later moved to NET's replacement, the Public Broadcasting Service, in late 1970. The Workshop officially became a company in 1970. Researchers Gerald S. Lesser and Edward L. Palmer helped create a special system. This system involved planning, production, and evaluation, and it helped TV producers and educators work together. This was later called the "CTW model." The CTW used this model for other TV shows too, like The Electric Company and 3-2-1 Contact.

In the early 1980s, the Workshop faced some challenges. It was hard to find audiences for their other shows. Some bad investments also caused problems for the organization. However, by 1985, agreements to license their shows helped stabilize their income. After Sesame Street became a big success, the CTW started other activities. These included publishing books and music, and creating shows with other countries. In 1999, the CTW teamed up with MTV Networks to create an educational channel called Noggin. They sold their share in Noggin to Viacom in 2002. The Workshop made many original shows for Noggin, such as The Upside Down Show, Sponk!, and Out There. In June 2000, the CTW changed its name to Sesame Workshop. This new name better showed that they did more than just TV shows.

By 2005, money from international versions of Sesame Street brought in $96 million. By 2008, the Sesame Street Muppets earned $15–17 million each year from licensing and merchandise. Sherrie Westin became the president of the company in 2021.

How Sesame Workshop Started

The Idea for Educational TV

In the late 1960s, almost all American homes had a TV. Young children watched about 27 hours of TV every week. Research showed that children who were ready for school did better in their classes. However, children from low-income families often had fewer resources to prepare them for school. Studies found that these children often scored lower in school-related skills. Scientists were also learning that early childhood education could help children's minds grow.

In 1966, Joan Ganz Cooney had a dinner party. Among her guests were Lloyd Morrisett and his wife. Joan Cooney was a documentary producer for a public TV station in New York. She had won an Emmy Award for a documentary about poverty. Lloyd Morrisett worked for the Carnegie Corporation. He was in charge of funding educational research. He was frustrated because his efforts weren't reaching many children who needed early education. Cooney wanted to use TV to improve society. Morrisett was interested in using TV to "reach greater numbers of needy kids." At the party, they talked about using television to teach young children. A week later, Cooney and Morrisett met to discuss studying the idea of an educational TV show for preschoolers. Cooney was chosen to do this study.

In the summer of 1967, Cooney took time off from her job. With funding from the Carnegie Corporation, she traveled across the U.S. and Canada. She interviewed experts in child development, education, and television. She wrote a 55-page report called "The Potential Uses of Television in Preschool Education." This report described what the new series, which became Sesame Street, would be like. It also suggested creating a company to manage its production. This company eventually became the Children's Television Workshop (CTW).

Creating the Workshop

For the next two years, Cooney and Morrisett researched and developed the new show. They raised $8 million to fund Sesame Street and set up the CTW. Cooney thought the show would naturally air on PBS. Morrisett was open to commercial stations, but all three major networks turned down the idea. This decision was later called "a billion-dollar blunder" because of Sesame Street's future success.

Morrisett was very good at getting money for the project. Cooney was in charge of the show's creative development. She also hired the production and research staff for the CTW. The Carnegie Corporation gave the first $1 million. Morrisett then got more large grants from the U.S. government, the Arthur Vining Davis Foundations, the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, and the Ford Foundation. A friend of Morrisett's, Harold Howe, who was the commissioner for the U.S. Department of Education, promised $4 million. This was half of the new organization's budget. The Carnegie Corporation gave another $1 million.

Cooney's plan included using research to improve the show as it was being made. It also included independent evaluations to see how the show affected young viewers' learning. In 1967, Morrisett asked Harvard University professor Gerald S. Lesser to help lead the Workshop's research department. Lesser also became the first chairman of the Workshop's advisory board. This board was special because it actively helped design the show. About 8–10% of the Workshop's first budget was spent on research.

The Workshop's first research director was Edward L. Palmer. He helped create the educational goals and research activities. Lesser and Palmer were the only scientists in the U.S. studying how children and television interacted at that time. They developed the "CTW model." Cooney said that the show was designed as an "experimental research project." It had educational advisers, researchers, and TV producers working together as equal partners.

The CTW spent 8% of its first budget on reaching out to people and publicity. They promoted the show to educators, the TV industry, and their target audience. This audience included children in inner cities and their families. They hired Evelyn Payne Davis to manage community relations. Bob Hatch was hired to publicize the new series before it started and during its first year.

Even though Cooney was involved from the start, some people questioned her becoming the executive director. They worried about her lack of experience in managing a company and with children's TV. Some also wondered if a woman could lead such a big project. However, with help from her husband and Morrisett, the investors realized they needed her. She was named to the position in February 1968. Her appointment was a big deal for women in American television. The Children's Television Workshop was officially announced on May 20, 1968.

After her appointment, Cooney hired Bob Davidson to make agreements with about 180 public TV stations. She also put together a team of producers: Jon Stone for writing and casting, David Connell for animation, and Samuel Gibbon to connect the production and research teams. These producers had worked together on Captain Kangaroo. Cooney later said that the original team was "a genius." Sesame Street first aired on November 10, 1969. The CTW officially became a company in 1970. Morrisett was the first chairman of CTW's board of trustees for 28 years.

Growth and Changes

Early Programs and Challenges

During the second season of Sesame Street, the Workshop created its second series, The Electric Company, in 1971. This show aimed to help children learn to read. The Electric Company stopped making new episodes in 1977 but was shown in reruns until 1985. It became one of the most used TV shows in American classrooms and was brought back in 2009.

In the early 1970s, the Workshop tried making shows for adults. However, it was hard to make these shows available to everyone. In 1971, they produced a medical show called Feelin' Good, which aired until 1974. This show didn't find a large audience. In 1977, the Workshop aired an adult drama called Best of Families, but it only lasted for a few episodes. After this, the Workshop decided to focus only on children's programs.

Throughout the 1970s, the CTW also focused on creating educational materials for preschools. They used mobile viewing units to show Sesame Street in inner cities, rural areas, Native American communities, and migrant worker camps. In the early 1980s, the CTW created the Preschool Education Program (PEP). This program helped preschools use Sesame Street as an educational tool by combining TV viewing, books, and activities. The Workshop also provided materials for children and adults who didn't speak English. Starting in 2006, the Workshop expanded its programs. They created PBS specials and DVDs about how military deployments affect soldiers' families. Other efforts included helping families of prisoners, promoting health, and teaching safety.

The 1980s were a tough time for the Workshop. Some bad investments in video games, movies, and theme parks hurt the company financially. Licensing agreements helped stabilize their income by 1986. Despite financial problems, the Workshop continued to make new shows. 3-2-1 Contact started in 1980 and ran for seven seasons. It was easy to find funding for this show and other science shows like Square One Television (1987-1992). This was because organizations like the National Science Foundation were interested in funding science education.

Recent Years and New Ventures

Joan Ganz Cooney stepped down as chairman and CEO of the CTW in 1990. David Britt, who had worked with her since 1975, took her place. Cooney then became chairman of the Workshop's executive board. In 1995, the Workshop reorganized and let go of about 12% of its staff. In 1998, for the first time, they accepted money from corporations for Sesame Street and other programs. This decision was criticized by consumer advocate Ralph Nader. The Workshop said it was necessary because government funding had decreased.

Also in 1998, the CTW invested $25 million in an educational cable channel called Noggin. Noggin was a partnership between the CTW and Viacom's MTV Networks. It launched on February 2, 1999. Creating a new channel helped the CTW ensure their programs reached more people. Noggin's early shows were mostly older programs from the CTW's library.

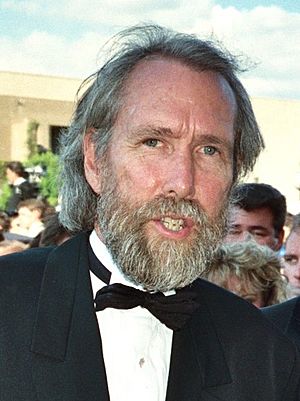

In 2000, profits from the Noggin deal and the popularity of "Tickle Me Elmo" helped the CTW. They bought The Jim Henson Company's rights to the Sesame Street Muppets from a German media company for $180 million. This deal also included a small share Henson had in the Noggin channel. Gary Knell, who became president and CEO in 2000, said everyone was happy to bring the Muppets "home." This protected Sesame Street and allowed the company to grow internationally.

The CTW changed its name to Sesame Workshop on June 5, 2000. This new name better showed that they did more than just TV. Under Gary Knell's leadership, Sesame Workshop made many original shows for Noggin. One was an interactive game show called Sponk!, which taught teamwork. Sesame Workshop also co-produced Play with Me Sesame, a Sesame Street spin-off, for Noggin. In April 2002, Noggin started an overnight block for teenagers called The N. Sesame Workshop created its first teen drama series, Out There, for The N.

In August 2002, Sesame Workshop sold its 50% share of Noggin to Viacom. This sale helped SW pay off debt. Sesame Workshop still worked with Noggin's programming. Viacom made a multi-year deal with Sesame Workshop to continue broadcasting their shows. The last show they worked on together was The Upside Down Show, which started in 2006.

Outside of Noggin, Knell helped create the cable channel Sprout (now Universal Kids) in 2005. Sprout was a partnership between the Workshop, Comcast, PBS, and HIT Entertainment. They all contributed older shows from their libraries to the new network. After seven years, the Workshop sold its share in Sprout to NBCUniversal in December 2012.

In 2007, the Sesame Workshop started The Joan Ganz Cooney Center. This independent organization studies how to improve children's reading skills. It focuses on using and developing digital technologies based on educational goals, just like Sesame Street was created.

The 2008–2009 economic downturn affected the organization. In 2009, they had to let go of 20% of their staff. In 2012, even with about $100 million from licensing and funding, the Workshop's total income was down. Their operating loss doubled to $24.3 million. In 2013, they let go of 10% more staff to focus their resources in the changing digital world. In 2011, Knell left Sesame Workshop to lead National Public Radio (NPR). H. Melvin Ming, who had been the chief financial officer, took his place. In 2014, H. Melvin Ming retired. Jeffery D. Dunn, who had worked for HIT Entertainment and Nickelodeon, became his successor. Dunn was the first manager not directly from CTW or Sesame Workshop. In 2021, Dunn retired. Sherrie Rollins Westin, who had been president of SW's Social Impact and Philanthropy Division, took over.

In 2019, The Hollywood Reporter said that Sesame Workshop's operating income was about $1.6 million. Most of their money from grants and licensing went back into creating content. Their total operating costs were over $100 million per year. These costs included salaries, rent for their offices, production facilities, and making content for YouTube. The organization employed about 400 people, including many skilled puppeteers. Money from royalties and distribution fees was their biggest income source, at $52.9 million in 2018. Donations brought in $47.8 million. Licensing income from games, toys, and clothing earned $4.5 million.

On March 6, 2025, Sesame Workshop announced plans to make its operations smaller. This was because Warner Bros. Discovery decided not to continue its US distribution deal for Sesame Street. Also, policy changes affected the organization's federal funding. On May 20, 2025, Sesame Street moved to Netflix after funding from the government was stopped.

How Sesame Workshop Gets Money

After Sesame Street became popular, the CTW started thinking about how to keep going. Their first funding sources were meant to start projects, not keep them running long-term. The organization was very popular with the government for a few years. However, its first ten years had conflicts with the government. In 1978, the US Department of Education held back a $2 million check until the very last day of the CTW's financial year. The government was against funding public television. But the Workshop used Joan Cooney's fame and the public's support for the show to resist these attacks. Eventually, the CTW got its own line in the federal budget. By 2019, the U.S. government gave about four percent of the Workshop's budget, which was less than $5 million a year.

For the first time, a public TV show could earn a lot of money. Right after Sesame Street premiered, marketers became interested. So, the Workshop looked into licensing, publishing, and international sales. It became a "multiple media institution." Licensing became the main way to fund the Sesame Workshop. This money could support the organization and future projects. Muppet creator Jim Henson owned the rights to the Muppet characters. He didn't want to market them at first. But he agreed when the CTW promised that profits from toys, books, and other products would only be used to fund the CTW. The producers insisted on having full control over all products. Any product linked to the show had to be educational, affordable, and not advertised during Sesame Street broadcasts. In the early 1970s, the CTW worked with Random House to create a division for non-broadcast materials. They hired Christopher Cerf to help publish books and other materials that matched the show's lessons. By 2019, Sesame Workshop had over 500 licensing agreements. Its total revenue from this in 2018 was $35 million. Millions of children play with Sesame Street-themed toys every day.

Soon after Sesame Street started, people from other countries asked for versions of the show. CBS executive Michael Dann joined the CTW as Joan Cooney's assistant. Dann started developing foreign versions of Sesame Street. These were called "co-productions." They were independent shows with their own sets, characters, and learning goals. By 2009, Sesame Street was in 140 countries. In 2005, The New York Times reported that income from international co-productions was $96 million. By 2008, the Sesame Street Muppets earned $15 million to $17 million per year from licensing and merchandise. In 1998, the Workshop started seeking money from corporate sponsors. Consumer advocate Ralph Nader asked parents to protest this by boycotting the show. In 2018, the Workshop made a deal with Apple to create original puppet series for Apple's streaming service. In 2019, Parade Magazine reported that the organization received two $100 million grants. These grants were from the MacArthur Foundation and the LEGO Foundation. The money was used to help refugee children and families.

Books and Publishing

In 1970, the CTW created a department to manage "nonbroadcast" materials based on Sesame Street. The Workshop decided that all licensed materials would support the show's learning goals. For example, coloring books were not allowed because the Workshop felt they limited children's imaginations. CTW published Sesame Street Magazine in 1970. This magazine included the show's curriculum goals. Research was done for the magazine, first by CTW's research department, then by the Magazine Research Group.

The CTW hired Christopher Cerf to manage Sesame Streets book publishing program. In its first year, this division earned $900,000 for the CTW. Cerf later left to write music for the series. Bill Whaley eventually replaced him. Ann Kearns, vice president of licensing for the CTW in 2000, said Whaley expanded licensing to other products. He also created a licensing model used by other children's series. As of 2019, the Workshop had published over 6,500 book titles. The print materials created by CTW have been a lasting part of Sesame Streets history. For example, the death of the Sesame Street character Mr. Hooper was featured in a book called I'll Miss You, Mr. Hooper in 1983. In 2019, Parade Magazine reported that 20 million copies of The Monster at the End of the Book and Another Monster at the End of this Book had been sold. These were the top two best-selling e-books. Their YouTube channel had almost 5 million subscribers.

Music of Sesame Street

The music of Sesame Street was different from other children's shows. For the first time, the songs had a specific purpose and were linked to the show's lessons. Joan Cooney noticed that children liked "commercial jingles." So, many of the show's songs were like TV advertisements.

To attract the best composers and lyricists, the CTW allowed songwriters to keep the rights to their songs. This meant writers could earn good money, which helped the show stay popular. Scriptwriters often wrote their own lyrics. Famous songwriters included Joe Raposo, Jeff Moss, Christopher Cerf, Tony Geiss, and Norman Stiles. Many Sesame Street songs have become "timeless classics." These include "Can You Tell Me How to Get to Sesame Street?", "I Love Trash", "Rubber Duckie", "Bein' Green", and "Sing". Many Sesame Street songs were recorded by famous artists like Barbra Streisand, Lena Horne, Dizzy Gillespie, Paul Simon, and Jose Feliciano. By 2019, 180 albums of Sesame Street music had been produced.

The show's first album, Sesame Street Book & Record, came out in 1970. It was a big success and won a Grammy Award. Parade Magazine reported in 2019 that the show's music had won 11 children's Grammys. Joe Raposo won three Emmys and four Grammys for his work on the series.

International Versions of Sesame Street

Soon after Sesame Street started in the US, producers from other countries asked to make their own versions. Joan Cooney was surprised because they thought they were making a very American show. But it turned out the Muppets were popular everywhere. She hired former CBS executive Mike Dann to manage these offers. Dann started arranging "co-productions."

The first international versions were simple. They were dubbed versions of the US show with local language voice-overs. If a country needed it, dubbed versions continued to be made. Later, a version of the CTW model was used to create independent preschool TV series in other countries. By 2006, there were twenty co-productions. In 2001, over 120 million people watched international versions of Sesame Street. By the show's 50th anniversary in 2019, 190 million children watched over 160 versions in 70 languages. In 2005, The New York Times reported that income from co-productions and international licensing was $96 million. In 2000, it was said that Children's Television Workshop (CTW) was the largest informal educator of young children in the world.

Digital and Interactive Media

Ten years after Sesame Street premiered, the CTW started trying new technologies. In 1979, they planned a theme park, Sesame Place, which opened in 1980 in Langhorne, Pennsylvania. Three international parks were later built: Parque Plaza Sesamo in Monterrey, Mexico, Universal Studios Japan, and Vila Sesamo Kids' Land in Brazil. One part of the park was a computer gallery with 55 computer programs. This team became the Children's Computer Workshop (CCW) in 1982. It later became the Interactive Technologies division of the CTW. Computer games can be very interactive. The CTW decided to use this to create educational software based on the TV series.

In 2008, Sesame Workshop started offering clips and full episodes on Hulu, YouTube, and iTunes. "Word on the Street" segments became very popular online. Sesame Workshop won a Peabody Award in 2009 for its website, sesamestreet.org. In 2010, the Workshop started offering over 100 eBooks for a subscription fee. The online publishing platform was managed by Impelsys.

See also

In Spanish: Sesame Workshop para niños

In Spanish: Sesame Workshop para niños

- List of Sesame Workshop productions

- Avenue Q

- Higher Ground Productions

- The Muppets Studio

| Precious Adams |

| Lauren Anderson |

| Janet Collins |