Siege of Sidney Street facts for kids

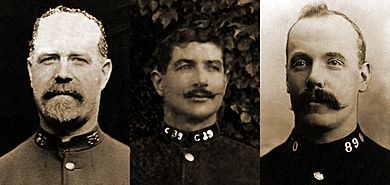

The siege of Sidney Street happened in January 1911 in the East End of London. It was a big gunfight between police and soldiers, and two Latvian revolutionaries. This event was the end of a series of incidents that started in December 1910. A group of Latvian immigrants tried to rob a jewellery shop in Houndsditch. During the robbery, three policemen were killed, two others were hurt, and the gang's leader, George Gardstein, also died.

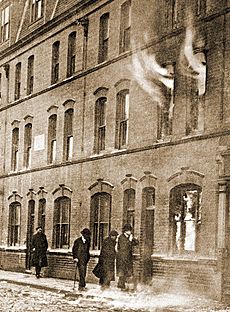

Police from both the Metropolitan and City of London Police forces investigated. They found most of Gardstein's friends, and arrested them within two weeks. The police then learned that the last two gang members were hiding at 100 Sidney Street in Stepney. Police moved local people out of their homes for safety. On the morning of 3 January, the gunfight began. The police had weaker weapons, so they asked the army for help. The siege lasted for about six hours. Towards the end, the building caught fire, but no one knows exactly how it started. One of the men inside was shot before the fire spread. While the London Fire Brigade was putting out the fire, they found the two bodies. The building then fell down, killing a fireman.

This siege was the first time police in London asked the military for help with an armed stand-off. It was also the first siege in Britain to be filmed, as Pathé News recorded the events. Some of the film showed Winston Churchill, who was the Home Secretary (a top government official in charge of police). His presence caused a political debate about how much he was involved. In May 1911, a trial was held for those arrested for the Houndsditch robbery. Almost everyone accused was found not guilty, and the one conviction was later overturned. The events were made into films, like The Man Who Knew Too Much (1934) and The Siege of Sidney Street (1960), and also into books. One hundred years after the events, two tall buildings in Sidney Street were named after Peter the Painter. He was a small part of the gang, but probably wasn't at either Houndsditch or Sidney Street. The policemen and the fireman who died are remembered with special plaques.

Contents

Background to the Siege

People Moving to London

In the 1800s, about five million Jewish people lived in the Russian Empire. This was the largest Jewish community at the time. They faced religious unfairness and violent attacks called pogroms. Many left their homes, and between 1875 and 1914, about 120,000 came to the United Kingdom, mostly to England. Most of these Jewish immigrants were poor and had few skills. They settled in the East End of London. In some areas, almost all the people were Jewish immigrants. A study in 1900 showed that Houndsditch and Whitechapel were very Jewish areas.

Some of these people who left their home country were revolutionaries. Many found it hard to live in London, which was much freer politically. A historian named William J. Fishman wrote that "crazy Anarchists were almost accepted as part of the East End." The British newspapers often used the words "socialist" and "anarchist" to describe people with revolutionary ideas. A newspaper article in The Times said that the Whitechapel area was a place that "harbours some of the worst alien anarchists and criminals."

Around 1900, gang fights happened in the Whitechapel and Aldgate areas of London. These were between groups from Bessarabia and people who had fled from Odessa. Different revolutionary groups were active there. In January 1909, two Russian revolutionaries in London, Paul Helfeld and Jacob Lepidus, tried to rob a payroll van. This event, called the Tottenham Outrage, left two people dead and twenty injured. This was a tactic often used by revolutionary groups in Russia. They would steal private property to get money for their radical activities.

Many people worried about the increase in immigrants and violent crime. Newspapers also talked about it. The government passed the Aliens Act 1905 to try and reduce immigration. The newspapers often showed what many people thought at the time. One article supported the law to stop "the dirty, destitute, diseased, verminous and criminal foreigner."

The Latvian Gang

By 1910, Russian immigrants often met at the Anarchist Club in Jubilee Street, Stepney. Many members were not anarchists, but the club was a place for Russian immigrants, mostly Jewish, to meet and socialize. The small group of Latvians involved in the Houndsditch and Sidney Street events were not all anarchists, though anarchist writings were found later among their things. They were likely revolutionaries who had become radical because of their experiences in Russia. They all had extreme left-wing political views. They believed that taking private property was a fair thing to do.

The likely leader of the group was George Gardstein. His real name was probably Poloski or Poolka. Gardstein was probably an anarchist. He had been accused of murder and terrorism in Warsaw in 1905 before coming to London. Another member, Jacob (or Yakov) Peters, had been an activist in Russia. He had been in prison for his activities. Fritz Svaars (Latvian: Fricis Svars) was a Latvian who had been arrested three times for terrorist acts in Russia but escaped each time. He had traveled through the United States, where he committed several robberies, before arriving in London in June 1910.

Another member was "Peter the Painter." This was a nickname for someone whose real name might have been Peter Piaktow or Janis Zhaklis. No one knows for sure about his background. William (or Joseph) Sokoloff (or Sokolow) was a Latvian arrested in Riga in 1905 for murder and robbery before coming to London. Karl Hoffman, whose real name was Alfred Dzircol, had been involved in revolutionary and criminal acts for years, including smuggling guns. In London, he worked as a decorator. John Rosen, whose real name was John Zelin or Tzelin, came to London in 1909 from Riga and worked as a barber. Max Smoller, also known as Joe Levi, was wanted in his home country for several jewel robberies.

Police in London

After laws were passed in 1829 and 1839, London was policed by two forces. The Metropolitan Police covered most of the city. The City of London Police was in charge of law enforcement within the historic City boundaries. The events in Houndsditch in December 1910 were handled by the City of London police. The later actions at Sidney Street in January 1911 were handled by the Metropolitan force. Both police services were controlled by the Home Secretary. In 1911, this was 36-year-old Winston Churchill.

When police officers were on their normal patrols, they carried a short wooden truncheon for protection. When they faced armed people, like at Sidney Street, the police were given Webley and Bull Dog revolvers, shotguns, and small rifles.

The Houndsditch Robbery, December 1910

In early December 1910, Smoller, using the name Joe Levi, visited Exchange Buildings. This was a small dead-end street behind the shops on Houndsditch. He rented a place at 11 Exchange Buildings. A week later, Svaars rented number 9 for a month, saying he needed it for storage. The gang could not rent number 10, which was directly behind their target: 119 Houndsditch, a jeweller's shop owned by Henry Samuel Harris. The safe in the shop was said to hold jewellery worth a lot of money. Over the next two weeks, the gang brought in tools, including a 60-foot gas hose, a gas cylinder, and special drills.

No one has ever fully confirmed who was in the gang at Houndsditch on the night of 16 December 1910, except for Gardstein. It is thought that Sokoloff and Peters were there. They likely shot the policemen who interrupted their burglary. Peter the Painter was probably not there that night.

On 16 December, the gang started breaking through the back wall of the shop from the yard behind 11 Exchange Buildings. Around 10:00 that evening, Max Weil, who lived at 120 Houndsditch, heard strange noises from his neighbor's property. Outside his house, Weil found Police Constable Piper on his patrol and told him about the noises. Piper checked nearby shops and heard the noise. He thought it was strange enough to investigate. At 11:00, he knocked on the door of 11 Exchange Buildings. A man opened the door in a sneaky way, and Piper immediately became suspicious. To avoid alarming the man, Piper asked him "is the missus in?" The man answered in broken English that she was out, and the policeman said he would return later.

Piper reported that as he left Exchange Buildings, he saw a man acting suspiciously in the shadows. When the policeman approached him, the man walked away. Piper later described him as being about 5 feet 7 inches tall, pale, and fair-haired. When Piper reached Houndsditch, he saw two other policemen. They watched 120 Houndsditch and 11 Exchange Buildings while Piper went to the police station to report. By 11:30, seven uniformed and two plain clothes policemen were in the area. Each had his wooden truncheon. Sergeant Robert Bentley knocked at number 11, not knowing Piper had already done so. This alerted the gang. Gardstein answered the door. Bentley asked if anyone was working there, but Gardstein did not respond. Bentley asked him to get someone who spoke English. Gardstein left the door half-closed and went inside. Bentley entered the hall with Sergeant Bryant and Constable Woodhams. They saw someone watching them from the stairs. The police asked if they could go to the back of the property, and the man agreed. As Bentley moved forward, the back door opened. One of the gang members came out, firing a pistol. The man on the stairs also started shooting. Bentley was shot in the shoulder and neck. Bryant was shot in the arm and chest, and Woodhams was wounded in the leg. Both Bryant and Woodhams survived, but never fully recovered.

As the gang left the building to escape, other police officers stepped in. Sergeant Charles Tucker was shot twice and died instantly. Choate grabbed Gardstein and fought for his gun, but Gardstein shot him in the leg. Other gang members ran to help Gardstein, shooting Choate many times. Gardstein was also wounded. As the policeman fell, Gardstein was carried away by his friends, including Peters. As these men, helped by an unknown woman, escaped with Gardstein, they were stopped by Isaac Levy, a passer-by. They threatened him with a pistol. The group, including Peters, went to Svaars' and Peter the Painter's lodging at 59 Grove Street. There, Gardstein was cared for by two of the gang's friends, Luba Milstein and Sara Trassjonsky. As they left Gardstein on the bed, Peters left his pistol under the mattress.

Other policemen arrived at Houndsditch and helped the wounded. Tucker's body was taken to the London Hospital in Whitechapel Road. Choate was also taken there and had surgery, but he died at 5:30 am on 17 December. Bentley was taken to St Bartholomew's Hospital. He was partly conscious and could talk to his pregnant wife and answer questions. At 6:45 pm on 17 December, his condition worsened, and he died at 7:30. The killings of Tucker, Bentley, and Choate are one of the largest murders of police officers in Britain during peacetime.

The Investigation (December 1910 – January 1911)

The City of London police told the Metropolitan force, as their rules required. Both police services gave revolvers to the detectives searching for the gang. The investigation was hard for the police. There were cultural differences between the British police and the many foreign residents in the search area. The police did not have officers who spoke Russian, Latvian, or Yiddish.

In the early hours of 17 December, Milstein and Trassjonsky became worried as Gardstein's condition got worse. They sent for a local doctor. They told him their patient had been accidentally wounded by a friend. The doctor thought the bullet was still in his chest. The doctor wanted to take Gardstein to the London Hospital, but he refused. The doctor sold them pain medicine and left. Gardstein died by 9:00 that morning. The doctor returned at 11:00 am and found the body. He had not heard about the events at Exchange Buildings the night before. So, he reported the death to the coroner, not the police. At midday, the coroner reported the death to the local police. Led by Detective Inspector Frederick Wensley, they went to Grove Street and found the body. Trassjonsky was in the next room, burning papers quickly. She was arrested and taken to police headquarters. Many of the papers found linked the suspects to the East End, especially to the anarchist groups there. Wensley knew the Whitechapel area well. He helped the City of London force throughout the investigation.

Gardstein's body was taken to a local morgue. His face was cleaned, his hair brushed, his eyes opened, and his photograph was taken. The picture and descriptions of those who helped Gardstein escape were put on posters in English and Russian. They asked local people for information. About 90 detectives searched the East End, sharing details of those they were looking for. A local landlord, Isaac Gordon, reported one of his lodgers, Nina Vassilleva. She had told him she was one of the people living at Exchange Buildings. Wensley questioned the woman. He found anarchist publications in her rooms, along with a photograph of Gardstein. Information started coming in from the public and the group's friends. On 18 December, Federoff was arrested at home. On 22 December, Dubof and Peters were both caught.

On 22 December, a public memorial service was held for Tucker, Bentley, and Choate at St Paul's Cathedral. King George V was represented there. Churchill and the Lord Mayor of London were also present. The crime had shocked Londoners, and the service showed how they felt. About ten thousand people waited around St Paul's. Many local businesses closed to show respect. The nearby London Stock Exchange stopped trading for half an hour so traders and staff could watch the procession. After the service, the coffins were taken on an eight-mile journey to the cemeteries. It is thought that 750,000 people lined the route. Many threw flowers onto the hearses as they passed.

Identity parades were held at Bishopsgate police station on 23 December. Isaac Levy, who had seen the group leaving Exchange Buildings, identified Peters and Dubof as the two he had seen carrying Gardstein. It was also confirmed that Federoff had been seen at the events. The next day, Federoff, Peters, and Dubof appeared at the Guildhall police court. They were charged with being connected to the murder of the three policemen and with planning to rob the jewellery shop. All three said they were not guilty.

On 27 December, Gardstein's landlord saw the poster with his picture and told the police. Wensley and his team visited the lodging on Gold Street, Stepney. They found knives, a gun, ammunition, fake passports, and revolutionary writings. Two days later, there was another court hearing. Milstein and Trassjonsky were also present. Interpreters were used because some of the accused did not speak English well. The case was put off until 6 January 1911.

On New Year's Day 1911, the body of Léon Beron, a Russian Jewish immigrant, was found on Clapham Common in South London. He had been badly beaten. The newspapers linked this case to the Houndsditch murders and the Sidney Street events. A historian found information that another Latvian said Beron was killed because he was planning to give information to the police. This act was meant to scare locals into not telling on the anarchists.

The posters of Gardstein worked. Late on New Year's Day, a member of the public came forward with information about Svaars and Sokoloff. The person told police that the men were hiding at 100 Sidney Street, along with a lodger, Betty Gershon, who was Sokoloff's girlfriend. The informant was asked to visit the property the next day to confirm the two men were still there. A meeting took place on the afternoon of 2 January to decide what to do next. Wensley, high-ranking Metropolitan police members, and Sir William Nott-Bower, the City Police Commissioner, were there.

Events of 3 January

Just after midnight on 3 January, 200 police officers from the City of London and Metropolitan forces surrounded the area around 100 Sidney Street. Armed officers were placed at number 111, directly across from number 100. Throughout the night, people living in the block were woken up and moved out for safety. Wensley woke the ground floor tenants at number 100. He asked them to get Gershon, saying her sick husband needed her. When Gershon appeared, police grabbed her and took her to the City of London police headquarters. The ground floor lodgers also left. Number 100 was now empty of all residents, except for Svaars and Sokoloff. They did not seem to know about the evacuation.

Police rules meant they could not open fire unless they were shot at first. This, along with the building's narrow, winding staircase, made it too dangerous for police to approach the gang members. They decided to wait until dawn before doing anything. At about 7:30 am, a policeman knocked on the door of number 100, but got no answer. Then, stones were thrown at the window to wake the men. Svaars and Sokoloff appeared at the window and started shooting at the police. A police sergeant was wounded in the chest. He was moved to safety across the rooftops and taken to the London Hospital. Some police officers shot back, but their guns were only good for shorter distances. They were not effective against the more advanced automatic weapons of Svaars and Sokoloff.

By 9:00 am, it was clear that the two gunmen had better weapons and plenty of ammunition. The police officers in charge, Superintendent Mulvaney and Chief Superintendent Stark, contacted Assistant Commissioner Major Frederick Wodehouse at Scotland Yard. He called the Home Office and got permission from Churchill to bring in a group of Scots Guards. They were stationed at the Tower of London. This was the first time the police had asked the military for help in London to deal with an armed siege. Twenty-one volunteer sharpshooters from the Guards arrived at about 10:00 am. They took firing positions at each end of the street and in the houses across the way. The shooting continued, with neither side gaining an advantage.

Churchill arrived at the scene at 11:50 am to see the incident himself. He later said he felt the crowd was not welcoming to him. He heard people asking "Who let 'em in?", referring to the Liberal Party's immigration policy. Churchill's exact role during the siege is not fully clear. Some historians believe he did not give direct orders to the police. However, a Metropolitan police history says it was "a very rare case of a Home Secretary taking police operational command decisions."

Shooting between the two sides was strongest between 12:00 and 12:30 pm. But at 12:50, smoke was seen coming from the building's chimneys and second-floor windows. It is not known how the fire started, whether by accident or on purpose. The fire slowly spread. By 1:30, it was burning strongly and had spread to other floors. A second group of Scots Guards arrived, bringing a Maxim machine gun, but it was never used. Soon after, Sokoloff put his head out of the window. He was shot by one of the soldiers and fell back inside. The senior officer of the London Fire Brigade asked for permission to put out the fire, but was refused. He asked Churchill to change the decision, but the Home Secretary agreed with the police.

By 2:30 pm, the shooting from the house had stopped. One of the detectives walked close to the wall and pushed the door open, then moved back. Other police officers and some soldiers came out and waited for the men to exit. No one did. As part of the roof fell down, it was clear to everyone watching that both men were dead. The fire brigade was then allowed to start putting out the fire. At 2:40, Churchill left the scene. Around that time, the Royal Horse Artillery arrived with two large field artillery guns. Sokoloff's body was found soon after the firemen entered. A wall fell on a group of five firemen. They were all taken to the London Hospital. One of the men, Superintendent Charles Pearson, had a broken spine. He died six months later. After making the building safe, the firemen continued their search. Around 6:30 pm, the second body, Svaars, was found.

Aftermath of the Siege

The siege was filmed by Pathé News cameras. It was one of their first stories and the first siege ever filmed. The footage included Churchill. When the newsreels were shown in cinemas, audiences booed Churchill and shouted "shoot him." His presence was controversial to many. The Leader of the Opposition, Arthur Balfour, said, "He [Churchill] was, I understand, in military phrase, in what is known as the zone of fire—he and a photographer were both risking valuable lives. I understand what the photographer was doing, but what was the right hon. Gentleman doing?"

An investigation was held in January into the deaths at Houndsditch and Sidney Street. The jury quickly decided that the two bodies found were Svaars and Sokoloff. They also decided that Tucker, Bentley, and Choate had been murdered by Gardstein and others during the robbery attempt. Rosen was arrested on 2 February at work. Hoffman was taken into custody on 15 February. The court hearings for those accused lasted from December 1910 to March 1911. In February, Milstein was released because there was not enough evidence against her. Hoffman, Trassjonsky, and Federoff were released in March for the same reason.

The case against the four remaining gang members was heard at the Old Bailey in May. Dubof and Peters were accused of Tucker's murder. Dubof, Peters, Rosen, and Vassilleva were charged with helping a murderer and planning to break into the jewellery shop to steal. The case lasted for eleven days. There were problems because of language difficulties and the complicated personal lives of the accused. Everyone was found not guilty except for Vassilleva. She was found guilty of planning the burglary and sentenced to two years in prison. However, her conviction was later overturned on appeal.

After much criticism of the Aliens Act, Churchill wanted to make the law stronger. He suggested a new bill to prevent crime by foreigners. However, a Member of Parliament named Josiah C Wedgwood disagreed. He wrote to Churchill, asking him not to introduce such strict measures. The bill did not become law.

What Happened Next

The police's weak weapons led to criticism in the newspapers. On 12 January 1911, several other weapons were tested. Because of these tests, the Metropolitan Police replaced their Webley revolver with a new semi-automatic pistol later that year. The City of London Police adopted the same weapon in 1912.

The members of the gang went their separate ways after the events. Peter the Painter was never seen or heard from again. It was believed he left the country. Jacob Peters returned to Russia and became a high-ranking official in the Soviet secret police. He was later executed in Joseph Stalin's purges in 1938. Trassjonsky had a mental breakdown and was kept in a mental hospital for a while. Her later life and when she died are unknown. Dubof, Federoff, and Hoffmann disappeared from records. Vassilleva stayed in the East End for the rest of her life and died in 1963. Smoller left the country in 1911 and went to Paris, then disappeared. Milstein later moved to the United States.

The siege was the idea for the final scene in Alfred Hitchcock's 1934 film The Man Who Knew Too Much. The story was also made into the 1960 film The Siege of Sidney Street. The siege also inspired two novels.

In September 2008, the Tower Hamlets London Borough Council named two tall buildings in Sidney Street Peter House and Painter House. Peter the Painter was only a minor part of the events and was not at the siege. The plaques on the buildings call Peter the Painter an "anti-hero". This decision made the Metropolitan Police Federation angry. A council spokesperson said that "There is no evidence that Peter the Painter killed the three policemen, so we knew we were not naming the block after a murderer. ... but he is the name that East Enders associate with the siege and Sidney Street." In December 2010, 100 years after the Houndsditch events, a memorial plaque for the three murdered policemen was revealed near the location. Three weeks later, on the anniversary of the siege, a plaque was revealed to honor Pearson, the fireman who died when the building fell on him.

| May Edward Chinn |

| Rebecca Cole |

| Alexa Canady |

| Dorothy Lavinia Brown |