Sliabh an Iarainn facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Sliabh an Iarainn |

|

|---|---|

| Slieve Anierin | |

Sliabh an Iarainn viewed from Lough Allen.

|

|

| Highest point | |

| Elevation | 585 m (1,919 ft) |

| Prominence | 245 m (804 ft) |

| Listing | Marilyn |

| Naming | |

| English translation | Mountain of the iron |

| Language of name | Irish |

| Geography | |

| Climbing | |

| Easiest route | Hike |

Sliabh an Iarainn (which means "iron mountain") is a big hill in County Leitrim, Ireland. Long ago, it was called Sliabh Comaicne, meaning "mountain of the Conmaicne people".

This mountain was shaped over millions of years by huge sheets of ice, called glaciers, moving across the land. These glaciers left behind many small hills called drumlins in the areas around the mountain. Sliabh an Iarainn is also important in old Irish stories and has special rocks with ancient fossils.

Contents

What's in a Name?

The name Irish: Sliabh an Iarainn, meaning mountain or moor of the Iron' comes from the Iron ore found there. In 1652, someone named Boate wrote that "the mountains are so full of this metal, that hereof it hath got in Irish the name of Slew Neren, that is, Mountains of Iron".

Before that, Sliabh an Iarainn was known as "Sliabh Comaicne". This meant "mountain of the Conmaicne Rein in Connacht", referring to an old Irish tribe. Even though the Irish spelling is common, people often say it like "Slieve-An-Ierin".

A Special Place for Fossils

Sliabh an Iarainn is a very important natural heritage site. This is because its rock layers have a complete record of Carboniferous marine fossils. These fossils show life from about 326 to 304 million years ago!

In 1878, the Geological Survey of Ireland said it was rare to find so many different rock formations in such a small area. They noted that you could see everything from older rocks up to the coal layers at the top of Sliabh an Iarainn.

A scientist named Patricia Yates studied the fossils here in 1962. She found a "remarkable extent" of ancient sea creatures called goniatites and bivalves (like clams). Some rock layers were full of these fossils.

She found that many layers had lots of goniatites and bivalves, but not many different types of species. The most diverse layer had Trilobites, brachiopods, gastropods, echinoids, and Bryozoa. Her work helped us understand the ancient life of this area.

Exploring the Mountain's Geography

Sliabh an Iarainn is a striking hill in western Ireland. It rises from the eastern side of Lough Allen. The summit is about 586-metre (1,923 ft) high.

At the very top, around 520 metres (1,706.0 ft) high, there is a special marker. This marker is a triangulation station used by the Ordnance Survey Ireland for mapping.

Mountain's Rock Layers

Sliabh an Iarainn is made of Carboniferous shales and sandstones. These rocks are covered by moorland with heather. The mountain is part of a larger area of Carboniferous rocks. This area stretches about 48 kilometres (29.8 mi) from Lough Erne to Lough Allen.

Shale is the main type of rock here. But there's also a thick layer of grit with coal seams deeper down. The mountain has a flat top and a steep grit slope. This slope can look like the summit from far away. However, the actual summit is another 50 metres (164.0 ft) higher, made of shale.

Much of the mountain top is covered by thick peat bog and glacial drift. The rocks usually lie flat or gently sloped. But there have been impressive landslides on the mountain's sides. This shows how much the land has moved over time.

Layers of Rock

The rocks from Lough Allen across Sliabh an Iarainn are in these main layers:

- Yoredale Beds or Namurian base:

- Coarse grits: 9 metres (29.5 ft) thick.

- Shales, limestones, and flags: 16.4 metres (53.8 ft) thick.

- Shales with ironstone modules: 241 metres (790.7 ft) thick.

- Millstone Grit:

- Crow coal with shale layers: 1.2 metres (3 ft 11.2 in) thick.

- Flag Grits: 2.4 metres (7 ft 10.5 in) thick.

- Shales: 500 metres (1,640.4 ft) thick.

- Coarse grits: 11 metres (36.1 ft) thick.

- Coal seat, with plant remains: 500 metres (1,640.4 ft) thick.

- Middle coal: 0.3 metres (11.8 in) thick.

- Shales: 3.7 metres (12.1 ft) thick.

- Coarse grits and flagstones: 23 metres (75.5 ft) thick.

- Lower coal measures:

- Shales with marine fossils: 228 metres (748.0 ft) thick.

The "Yoredale beds" go down to the edge of Lough Allen. From the base of the Namurian period upwards, shales are continuous. They continue until the millstone grit layer.

Coal Mining History

Sliabh an Iarainn is the eastern part of the Connacht coal field. You can see clear escarpment lines, which are steep slopes formed by geological faults. These faults have caused layers of rock to collapse.

Two coal seams, called crow coals and middle coal, can be found here. They are hard to trace because they are often covered by thick peat bog. Attempts to mine coal here in 1962 were stopped. The coal was not good quality, and the seams were not continuous.

Ancient Forests

Long ago, Ireland was covered in thick forests. A survey of Leitrim from the 1800s said that "a hundred years ago almost the whole country was one continued, undivided forest". You could travel from tree to tree for miles!

These huge forests in Leitrim and near Lough Allen were cut down. The timber was used to make charcoal. This charcoal was needed to fuel the iron works around Sliabh an Iarainn. By 1782, there were huge piles of cut timber in Drumshanbo.

Mountain Stories and Legends

The Tuatha Dé Danann

The ancient Irish book, The Book of Invasions, tells a fascinating story. It says the Tuatha Dé Danann, a magical group of people, arrived in Ireland by air. They landed their floating ships on top of Sliabh an Iarainn.

The story says they brought darkness over the sun for three days and three nights. The Tuatha Dé Danann met the Fir Bolg, another ancient group, at Magh Rein below the mountain. They fought, and the Tuatha Dé Danann won the Battle of Moytura. Later, the Tuatha Dé Danann moved into the Celtic Otherworld.

For there by old tradition the Tuatha de Danann had first descended from heaven, giving to Sliab in larainn its peculiar sanctity. Among the old races skilled craftsmen, as we may still see in the Dublin Museum, proved their talent.

Gobán Saor, the Master Smith

Metalworkers were highly respected in ancient Ireland. The legendary Irish craftsman Gobán Saor is like the famous smiths from other cultures. He is linked to Goibniu of the Tuatha Dé Danann.

Local stories say that Gobán Saor, a Tuatha Dé Danann metalsmith, worked in the mines of Sliabh an Iarainn.

Ancient Aliens Theory

Some people who study history in a different way suggest something unusual. They think that the old story in the Book of Invasions about the Tuatha Dé Danann arriving in Ireland might describe something else. They believe it could be about "the arrival of aliens in spacecraft with cloaking devices" at Sliabh an Iarainn.

The Hunger Stone

In the old parish of Kiltubrid, there was a belief about a "hungry man" (Irish: fear gorta). This was a sudden, intense hunger that could strike someone on the mountains. It was said to be deadly if not quickly satisfied.

This hunger was believed to affect anyone who stepped on a special "fear-gorta stone" at the base of Sliabh an Iarainn.

Fairies' Revenge

An old story from Cavan tells of a man named "Turlough the Yellow-haired". He supposedly asked the mountain fairies to destroy the Swanlinbar Iron works. He wanted them to send the foreign workers away.

The story says "the flood came rushing down from the mountain... and it left neither mill nor wig nor man behind but swept them all down to Lough Erne".

Iron Industry on the Mountain

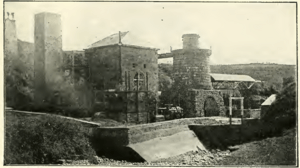

Iron ore has been dug from Sliabh an Iarainn since the 1600s. The ore was very tough, like Spanish iron. Commercial iron works were set up around Sliabh an Iarainn around c. 1630.

Many of these works were destroyed during the Irish Rebellion of 1641. But they were rebuilt after the Irish Confederate Wars or in the 1690s. Many iron works hired English or other foreign workers instead of Irish people. This caused a lot of anger locally.

The iron works were built near Lough Allen. This allowed pig iron to be transported by boats. Commercial iron mining started to decline after c. 1750 – c. 1760. This was because cutting down too many trees for charcoal fuel caused deforestation.

Cornashamsoge Furnace

In the 1600s, the Cornashamsogue smelting works were built. Local stories say that around 1650, there was a furnace for melting iron ore in Cornashameogue. The place where the furnace stood can still be pointed out. The field it was in is even called "Furnace Meadow".

Sliabh an Iarainn Leat

Local stories also mention a "Sliabh an Iarainn canal" linked to the Cornashamsoge smelting works. It was said that the iron ore had to be moved about 3 miles to the furnace. So, a canal was built for this purpose.

The canal ran along the foot of the mountain. Rivers flowing from the mountain into Lough Allen fed this canal. The water also powered the furnace. Today, only very small traces of this "canal" remain. It was more likely a Leat, which is a channel that carries water to a mill or works.

Drumshanbo Furnace

After the ironstone was melted, the Pig iron was taken to the Drumshanbo Finery forge. This forge was south of Lough Allen. There, it was turned into malleable (bendable) iron. This iron was then shipped to Dublin and Limerick by boat.

People believe the town of Drumshanbo grew because of these industries. The Drumshanbo Iron works closed in 1765.

Other Iron Works

- Ballinamore Iron works: This iron works was set up after 1693. It probably stopped making iron around 1747.

- Creevlea Iron works: This was the last iron works in Ireland. It closed around 1770 but reopened later. It finally stopped production in 1858.

- Swanlinbar Iron works: There was an iron works in Swanlinbar in county Cavan. But it had closed by 1785.

Literary Project

A special project called the "Sliabh an Iarainn project" started in 2004. Its goal was to write about the history of the people living around Sliabh an Iarainn and Ben Croy. This project aimed to remember the "Ultachs," who were Catholic refugees from Ulster. They came to the mountain in 1795.

The project recorded their experiences with famine and emigration. It also showed how the remaining communities were strong and resilient. This history was published in three books:

- Mountain Echoes, Sliabh an Iarainn's Story (Vol. 1)

- Mountain Shadows, Sliabh an Iarainn's Story (Vol. 2)

- Mountain Roots, Sliabh an Iarainn's Story (Vol. 3)

Historical Land Ownership

In 1609, during the Plantation of Ulster, Sliabh an Iarainn was given to John Sandford. He later sold it to his wife's uncle, Toby Caulfeild, 1st Baron Caulfeild.

Muintir-Eolais Lake

In the remote uplands of Cuilcagh-Anierin, there is a clear lake called "Lough Munter Eolas". This lake is named after Eolais Mac Biobhsach and the Muintir Eolais. They were a famous group of the Conmaicne Rein tribe. This lake is on the border of Moneensauran townland in west Cavan and Slievenakilla townland in south Leitrim.

Images for kids