Southern Rhodesia in World War I facts for kids

When World War I began in August 1914, people in Southern Rhodesia were very excited and patriotic. Southern Rhodesia was then managed by the British South Africa Company. The leader, Sir William Milton, told the UK government that "All Rhodesia ... ready to do its duty."

Even though the Company supported Britain, it worried about money. So, most of Southern Rhodesia's help came from its people. They volunteered to fight or raised money for food and supplies.

Many white Southern Rhodesians paid their own way to England to join the British Army. Most of them fought on the Western Front in Europe. They joined different British and South African units. Many joined the King's Royal Rifle Corps, which formed special Rhodesian platoons. These soldiers were known for their excellent shooting skills. Some also joined the Royal Flying Corps, which later became the Royal Air Force.

Other Rhodesian units, like the Rhodesia Regiment and the Rhodesia Native Regiment, fought in Africa. They helped in campaigns in South-West Africa and East Africa.

Southern Rhodesia did not force people to join the army. But, compared to its white population, it sent more soldiers to the British war effort than any other British colony. About 5,716 white men, which was 40% of all white men in the colony, joined up. Around 1,720 of these became officers. The Rhodesia Native Regiment had 2,507 black soldiers. About 30 black scouts helped the Rhodesia Regiment. Around 350 black soldiers served in British and South African units.

More than 800 Southern Rhodesians of all races died during the war. Many more were seriously wounded.

The colony was very proud of its efforts in the war. This helped the UK government decide to give Southern Rhodesia self-government in 1923. The war remained important in people's minds for many years. When Rhodesia declared independence from Britain in 1965, it did so on Armistice Day, November 11th, at 11:00 AM.

After Zimbabwe became independent in 1980, the new government removed many war memorials. They saw them as reminders of white minority rule. Because of this, the First World War is largely forgotten in Zimbabwe today.

Contents

How the War Started

Before World War I, Southern Rhodesia was controlled by the British South Africa Company. In 1911, there were 23,606 white people in Southern Rhodesia. This was a small part of the total population.

The Company's right to rule was supposed to end in 1914. People in Southern Rhodesia were discussing whether the Company should continue to rule. Some wanted the Company to stay. Others wanted Southern Rhodesia to become a self-governing colony within the British Empire. Some even wanted it to join the Union of South Africa. When the war started, the Company's right to rule was extended for 10 more years.

Southern Rhodesia's police force was the British South Africa Police (BSAP). It was also the country's army. By 1914, it had about 1,150 men. There were also the Southern Rhodesia Volunteers. This was an all-white group of about 2,000 men. They were not well-trained or equipped for a big war. Their contracts only allowed them to serve within Rhodesia.

First Steps to War

A few days after the war began, the Company created the Rhodesian Reserves. This was a group for white men who wanted to join the army. Important citizens formed their own small groups of 24 volunteers. These groups were like the "Pals battalions" in Britain.

The Company suggested sending 500 Rhodesian soldiers to Europe. But the British War Office said it would be better to send them to Africa. The South Africans agreed to take the Rhodesians, but only if they joined existing South African units. The Company found itself with soldiers no one seemed to want as a separate unit.

So, some Rhodesians decided to go to Britain on their own. They joined the British Army directly. By the end of October 1914, about 300 were on their way.

Fighting in Europe

The Western Front

Southern Rhodesia's main contribution to the war was in the trenches of the Western Front. White Rhodesians joined the British Army separately. They were spread across many regiments. These included the Black Watch and the Royal Engineers.

A special link grew with the King's Royal Rifle Corps (KRRC). This corps had the largest group of Rhodesians on the Western Front. The connection started by chance on a ship in late 1914. The Marquess of Winchester met Captain John Banks Brady, who led the Rhodesian volunteers. The Marquess suggested that the Rhodesians join the KRRC. This way, he could help keep an eye on them.

A special "Rhodesian Platoon" was formed under Brady. It was at the KRRC training camp in Sheerness, England.

Rhodesians overseas were very proud of Rhodesia. They saw fighting in "Rhodesian" groups as a way to create a unique national identity. They also hoped it would help Southern Rhodesia gain self-government. The Rhodesian Platoon in the KRRC became very popular back home. It attracted many more volunteers.

Rhodesians were used to rifles from their life in Africa. At Sheerness, Brady's Rhodesian Platoon became known for its excellent shooting. They even set a new shooting range record for the regiment.

The Rhodesian Platoon went to France in December 1914. They immediately started to suffer heavy losses. New Rhodesian volunteers kept arriving in England. But casualties were often so high that it took months for units to get back to full strength.

When the KRRC's Rhodesian platoons attacked, they had a special battle cry. Sometimes, British and German trenches were so close that soldiers could hear each other. Rhodesians would speak a mix of Shona and Sindebele (African languages) to avoid being understood.

Life in the trenches was very hard. Rhodesians, used to the warm African veld, struggled with the cold and mud. Many got frostbite. Despite this, their commanders were impressed. Lieutenant-Colonel Sir Edward Hutton said the Rhodesian soldiers "earned for itself great reputation for valour and good shooting."

Rhodesians were especially good as snipers and grenadiers. Hutton noted their skill in sniping. He said they were "accustomed to big game shooting." One group of 24 southern African snipers reportedly caused over 3,000 German casualties.

Many Rhodesians were chosen for officer training. In mid-1915, Brady asked for more volunteers to replace them. A Rhodesian platoon fought in the Battle of the Somme on July 1, 1916. Out of 90 Rhodesians, only 10 were alive and unwounded afterwards.

Rhodesians also fought at Delville Wood starting July 14. This was a terrible battle. The South African 1st Infantry Brigade, which included Rhodesians, lost about 80% of its men. But they held the Wood as ordered.

German gas attacks were very traumatic. One survivor said it felt like "suffocation, [or] slow drowning." Gas attacks caused extreme pain and lasting injuries to eyes and lungs.

In July 1917, a British officer praised a KRRC Rhodesian platoon. He called them "absolutely first-class soldiers." Around the same time, a Rhodesian platoon fought near Nieuwpoort in Belgium. They were surrounded by German soldiers. Most were killed or captured in brutal hand-to-hand fighting. The Bulawayo Chronicle newspaper compared their last stand to a famous Rhodesian battle. Later in 1917, a Rhodesian platoon fought in the Battle of Passchendaele.

Rhodesian troops kept arriving on the Western Front until the war ended.

Aviators

Some Southern Rhodesians joined the Royal Flying Corps (RFC). This group later became the Royal Air Force. From October 1918, Rhodesian airmen wore "RHODESIA" patches on their uniforms.

Lieutenant Arthur R H Browne was one of the first Rhodesian military pilots. He died in a dogfight in December 1915. His plane, "Gatooma No. 2," was bought with money donated by the people of Gatooma. Lieutenant Frank W H Thomas also served. He won the Military Cross and the French Croix de Guerre before he died from wounds in 1918.

Lieutenant Daniel S "Pat" Judson, born in Bulawayo in 1898, was the first airman born in Rhodesia. He joined the RFC in 1916. He was badly wounded in 1918 but recovered.

Major George Lloyd, nicknamed "Zulu," was the first flying ace born in Rhodesia. He shot down eight German planes. He won the Military Cross and the Air Force Cross.

Second Lieutenant David "Tommy" Greswolde-Lewis, from Bulawayo, was the 80th and final pilot defeated by Manfred von Richthofen, the famous German ace known as the Red Baron. Lewis's plane caught fire, but he was mostly unhurt. He spent the rest of the war as a German prisoner.

Arthur Harris, originally from England, also joined the RFC. He had served with the 1st Rhodesia Regiment in South-West Africa. He commanded squadrons on the Western Front. He won the Air Force Cross. Harris stayed in the RAF and became famous in World War II as "Bomber Harris."

Fighting in Africa

1st Rhodesia Regiment in South-West Africa

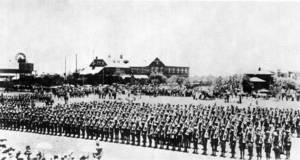

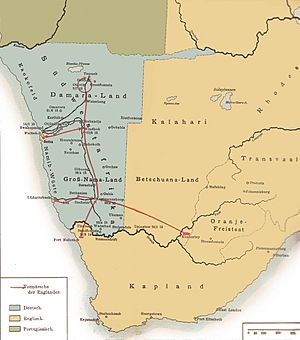

In September 1914, a former Boer commander, Lieutenant-Colonel Manie Maritz, rebelled against South Africa. He hoped to bring back the old Boer Republics. South Africa asked for the 500-man unit that the British South Africa Company had raised. This unit was named the 1st Rhodesia Regiment. It was made up of white soldiers, plus a small group of Matabele scouts.

The 1st Rhodesia Regiment trained in Salisbury for six weeks. Then they traveled south by train in October 1914. The rebellion was almost over by the time they arrived. Most South African troops stayed loyal to their government. The Rhodesians guarded Bloemfontein for a month. Then they went to Cape Town for more training for the South-West Africa Campaign.

In December 1914, the 1st Rhodesia Regiment landed at Walvis Bay in German South-West Africa. This was part of a plan to surround the German forces. The main target was Windhoek, the capital. The area was a very dry desert. Temperatures could go from over 50°C (122°F) in the day to below freezing at night.

The South African attack began in February 1915. The 1st Rhodesia Regiment had its first fights. They lost two men in a German ambush. The Rhodesians mostly guarded railway construction. They also helped win a battle at Trekkopjes. Windhoek surrendered in July 1915, ending the South-West African part of the war.

The 1st Rhodesia Regiment returned to Cape Town. Many soldiers were unhappy because there wasn't much fighting. They wanted to go to Europe. The regiment was soon disbanded because most men left to join the war in Europe.

2nd Rhodesia Regiment in East Africa

A second Rhodesian unit, the 2nd Rhodesia Regiment (2RR), was formed in late 1914 and early 1915. Recruiters promised that these men would definitely see combat in Africa. The 2RR had 500 men and 30 black scouts.

The 2RR received better training than the 1st Regiment. They trained for eight weeks, focusing on marching and shooting. They could shoot accurately up to 600 meters. The 2RR left Salisbury on March 8, 1915. They sailed to Mombasa in British Kenya, near German East Africa. They were sent to the area around Mount Kilimanjaro. Their commander said, "I will pay you the highest compliment by sending you to the front today."

The 2RR fought well in its first year. They usually defeated German units. But the Germans often retreated before they could be captured. The Germans also had longer-range artillery.

Tropical diseases caused more deaths and illnesses than German soldiers. At times, the regiment had fewer than 100 men fit for duty. Diseases like trench fever, dysentery, and sleeping sickness were common. On average, a 2RR soldier was hospitalized twice and reported sick 10 times.

By January 1917, only 91 men were fit for duty. The regiment was no longer effective. It was pulled out of East Africa that month. The healthy men returned to Salisbury in April 1917. Most of the 2RR remained in medical care overseas. The regiment was then dissolved. Most of its remaining men went to fight in Europe.

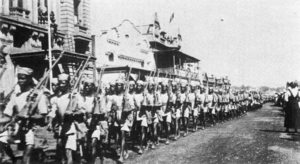

Rhodesia Native Regiment

By late 1915, British forces in Northern Rhodesia and Nyasaland were struggling with disease. Francis Drummond Chaplin, the Company administrator, offered to provide 500 to 1,000 black soldiers. Recruitment began in May 1916.

The unit was first called the "Matabele Regiment." But it was changed to the "Rhodesia Native Regiment" (RNR) on May 15, 1916. This was because it included many different groups, like Mashonas and Kalanga. White officers often knew an African language or a mix of languages called "Chilapalapa." Sometimes, soldiers misunderstood orders because of language differences.

The RNR, with 426 black soldiers and about 30 white officers, left Salisbury in July 1916. They went to Nyasaland for training. Then they moved into German East Africa. In October 1916, the RNR split up. One company went north, and the rest went south to Songea.

The Germans tried to retake Songea in November 1916. A German column attacked an RNR patrol. Sergeant Frederick Charles Booth bravely led the defense. He rescued a wounded scout under enemy fire. For this, Booth received the Victoria Cross in June 1917.

The Germans besieged Songea for 12 days but could not take it. The RNR later captured a German naval gun from a sunken ship.

The Company decided to raise a second RNR battalion in January 1917. The first was called 1RNR, and the new one 2RNR. They mostly recruited black men from other countries, like Nyasaland.

1RNR fought a difficult battle near the Northern Rhodesia border. They suffered heavy losses. The commander, Tomlinson, was blamed. He was wounded and sent home.

1RNR then marched for 53 days, covering long distances. Scholars say their physical endurance was amazing. They could march 50 km in a day. Black soldiers were more resistant to tropical diseases than white soldiers. In June 1917, Sergeant Rita received the Distinguished Conduct Medal for his bravery.

1RNR and 2RNR joined forces in January 1918. They chased the German commander Lettow-Vorbeck through Portuguese Mozambique. In May 1918, the two-year contracts for the original RNR volunteers ended. Most went home. They received a huge welcome in Salisbury.

The RNR chased Lettow-Vorbeck for over 3,600 km. They never caught him. He surrendered after the war ended in Europe. The RNR returned to Salisbury and was disbanded in 1919.

Life at Home During the War

Volunteers and Conscription

All Southern Rhodesian troops in World War I were volunteers. Not all men were expected to go fight. Many worked in important industries like mining. The Company did not give money to support families of married soldiers. So, at first, only single men in non-essential jobs were expected to join. The 2nd Rhodesia Regiment even banned married men.

Men who stayed home were encouraged to join the Southern Rhodesia Volunteers or Rhodesian Reserves. Newspapers said that if not enough men volunteered, conscription (forced service) might be needed.

Conscription was new for Britain, but it started there in January 1916. Some in Southern Rhodesia supported it, but many opposed it. The British South Africa Company worried about losing skilled white workers for its mines. Farmers also said they needed to stay on their land. Some felt that white men were needed in the colony to prevent local uprisings.

By late 1916, most who wanted to volunteer had already done so. In 1917, the Company considered compulsory service for whites. But this idea was very unpopular, especially with farmers. The Company dropped the idea after the war ended.

Money and Business

The British South Africa Company wanted to keep the colonial economy going. Prices for many items went up, and exports dropped. But mining, which was very important, continued to do well. The Company produced record amounts of gold and coal in 1916. They also started supplying ferrochrome, a strategic metal.

Farming did not do as well. It was hard to export food from Rhodesia. The colony sent Rhodesian butter to England starting in 1917.

The war began to hurt the economy in late 1917. The Company raised the income tax in 1918. By the end of the war, the Company had spent £2 million on the war effort. Most of this was paid by Rhodesian taxpayers.

Propaganda and Public Opinion

Newspapers like the Rhodesia Herald printed stories about German crimes. They also told stories of brave British soldiers. There was strong anti-German feeling throughout the war.

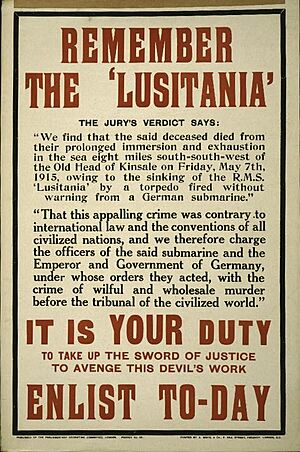

Many German and Austrian men in Rhodesia were arrested and sent to camps in South Africa. After a German submarine sank the British ship RMS Lusitania in May 1915, anti-German feelings grew stronger. Most remaining German and Austrian residents were sent to camps.

A small group of educated black people in towns supported the war effort. But most black people lived traditional lives in rural areas. For them, the war was a "white man's war" that did not concern them. Some rumors spread that the Company planned to force black people into the army. This did not happen.

The Company worried about a possible black rebellion. They passed laws to imprison popular spiritual leaders who might encourage uprisings. There was one small threat of rebellion in May 1916. This happened when the Company started recruiting for the Rhodesia Native Regiment. Some rumors said black men would be forced to join. But it became clear that conscription was not happening.

The small Afrikaner community in Rhodesia was divided. Some supported Britain, but others were still angry about the Anglo-Boer War. Some saw Germans as possible liberators from British rule.

Women's Role

In Southern Rhodesia, there were almost twice as many white men as women. Most white women did not work outside the home. They managed their households with the help of black labor. This was different from Britain, where many women worked in factories and farms. In Rhodesia, there were no munitions factories. Women working in mines was not practical.

White women mainly helped the war effort by organizing donation drives. They sent "comforts parcels" to soldiers. These packages contained knitted items, newspapers, soap, food, and small luxuries. These greatly helped soldier morale. Women also handled mail between soldiers and their families. After the war, they helped soldiers who couldn't afford to return home.

Some women gave white feathers (a symbol of cowardice) to men not in uniform. This often went wrong, as many men were medically unfit for service. Newspapers started publishing lists of men deemed unfit to prevent further harassment.

Black women sometimes accompanied black soldiers. They performed domestic tasks like washing and cooking. Officers allowed this to keep morale high.

Donations and Funds

Rhodesians set up many wartime funds. These raised about £200,000. Much of this went to the Prince of Wales National Relief Fund in Britain.

The Tobacco Fund, started in September 1914, was very successful. Donors bought Rhodesian tobacco to send to British forces. This also helped advertise Rhodesia for people who might want to move there after the war. The tobacco tins had a map of Africa with the sun shining on Rhodesia. The slogan was "The World's Great Sunspot." British soldiers received "Sunspot" cigarettes.

From July 1915, Rhodesians raised money to buy planes for the Royal Flying Corps. The colony bought three planes, named Rhodesia Nos. 1, 2, and 3. The town of Gatooma bought two more.

The small black elite in towns also donated to war funds. Rural black people often misunderstood the idea of donating money. They sometimes thought it was a new tax. Officials had to explain that contributions were voluntary. The Kalanga community gave a lot of money, donating £183 to the Prince of Wales Fund in June 1915.

Flu Pandemic

The 1918 flu pandemic, also called "Spanish flu," spread to Southern Rhodesia in October 1918. Public buildings became hospitals. Nurses were asked to help. Soup kitchens fed children whose parents were sick. The flu hit mine compounds the hardest. Thousands died across the country. Many Rhodesia Native Regiment soldiers died from the flu after surviving the war. The pandemic ended in Southern Rhodesia around mid-November 1918.

End of the War and Its Impact

News of the armistice on November 11, 1918, reached Southern Rhodesia the same day. People celebrated with street parties and bonfires.

After the celebrations, people thought about how soldiers would return to society. The Company had set aside 250,000 acres of farmland for white war veterans. In 1919, a government department was set up to help returning men find jobs. But many struggled to find work. Some seriously wounded soldiers stayed in England for better medical care.

The Southern Rhodesian tribal chiefs sent their own message to King George V.

Southern Rhodesia sent more people to the British armed forces, compared to its white population, than any other British colony. About 40% of white men (5,716) joined the army. The Rhodesia Native Regiment had 2,507 black soldiers. Over 800 Southern Rhodesians of all races died. More than 700 white servicemen died, and 146 black soldiers from the Rhodesia Native Regiment died.

What Happened Next

Stories about white Rhodesian soldiers were published in the 1920s. The war became a key part of the colony's history. White Rhodesians were very proud of their high enlistment rate. A national war memorial, a stone obelisk, was built in Salisbury in 1919. It had sculptures of black and white soldiers. Another monument, a stone cross, was built near Umtali to remember fallen black soldiers.

Southern Rhodesia's help in the war made Britain see it as more mature. So, Britain granted it self-government in 1923. Southern Rhodesia then started its own selective conscription for white men in 1926. The Rhodesia Regiment was reformed. It adopted parts of the KRRC uniform.

In World War II, Southern Rhodesia again strongly supported the UK. It declared war on Germany before any other colony. Over 26,000 Southern Rhodesians served. Special Rhodesian platoons served in the KRRC again. The Rhodesian African Rifles, formed in 1940, were similar to the Rhodesia Native Regiment. Southern Rhodesia also became known for military aviation. It provided squadrons to the Royal Air Force and trained 8,235 Allied airmen.

By the 1960s, Southern Rhodesians were very proud of their service in the World Wars. When the colonial government declared independence in 1965, it did so on November 11th, Armistice Day. This was to highlight its war record.

After Zimbabwe became independent in 1980, the government removed many war monuments. They saw them as reminders of white minority rule. Many Zimbabweans today see their nation's involvement in the World Wars as a result of colonial rule. They have little interest in these conflicts.

Today, the fallen soldiers of the two World Wars have no official commemoration in Zimbabwe. The national war memorial obelisk still stands, but its sculptures and inscriptions have been removed. The stone cross monument near Mutare (formerly Umtali) is one of the few memorials that remains. Its meaning has largely been forgotten.

| Bessie Coleman |

| Spann Watson |

| Jill E. Brown |

| Sherman W. White |