Spanish parliamentarism facts for kids

Spanish Parliamentarism is about how Spain has been governed through elected representatives over many centuries. It's a system where people choose their leaders, and these leaders then make laws and keep an eye on the government. This tradition goes way back to the Middle Ages in Spain, similar to how parliaments started in other European countries like England and France.

Contents

Early Parliaments: Up to the 17th Century

The first Spanish parliaments were called the Cortes. They grew out of an older royal council around the late 1100s. These Cortes were a way for the king and the "kingdom" (meaning the people and different groups) to connect regularly.

The very first Cortes that included representatives from cities met in León in 1188. King Alfonso IX called this meeting.

The Cortes met often in the late Middle Ages and up to the mid-1600s. In the Crown of Castile, their main job was to approve taxes. In the kingdoms of the Crown of Aragon and Navarre, the Cortes had more power because the kings there had less absolute control.

Even when the different Spanish kingdoms united, each kingdom kept its own Cortes. The Cortes of Castile became the most important for raising money for the kings during the 1500s and 1600s. By the late 1600s, the Cortes were hardly called together anymore.

Here are some of the different Cortes that existed:

- Cortes of Aragon

- Cortes of Castile

- Catalan Courts

- Cortes of León (the first in 1188; later met with Castile)

- Cortes of Navarre (met until 1829)

- Portuguese Cortes

- Valencian Cortes

The island of Majorca did not have its own Cortes. Its Gran i General Consell served a similar purpose. Majorcan representatives did attend the Cortes of the Crown of Aragon when they met together.

The 18th Century: Bourbon Changes

After the War of the Spanish Succession (1700-1715), the new Bourbon kings changed things. They issued the Nueva Planta Decrees, which removed the special laws of the Crown of Aragon. This allowed the king to call all the Cortes of the Spanish kingdoms together (except Navarre). These new joint meetings were called the Cortes Generales del Reino (General Courts of the Kingdom).

They only met twice in the entire 18th century:

- Cortes of Madrid of 1713: King Philip V called these Cortes. They approved the Salic Law, which meant women could not inherit the throne. This was a French tradition.

- Cortes of Madrid of 1789: King Charles IV called these Cortes to swear in his son Ferdinand (who would become Ferdinand VII). He also used this chance to get rid of the Salic Law.

The 19th Century: A Time of Big Changes

Parliament in Cádiz

Spain's political life in the 1800s was very busy. This was clearly seen in how parliament changed.

The Cortes of Cadiz were very important. They started modern liberal parliamentarism in Spain. This included ideas like:

- National sovereignty: Power belongs to the people.

- Universal suffrage: Everyone can vote (though at first, it was only men).

- Separation of powers: Government power is split into different branches.

- Recognizing rights: People have basic freedoms.

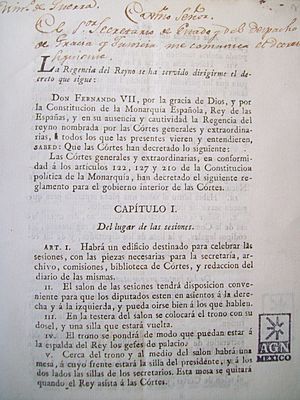

These Cortes met in Cadiz starting in 1810 because it was the only city safe from the French invasion. They had lively debates and made revolutionary laws. They held all the power because King Ferdinand VII was held captive in France by Napoleon.

The deputies in Cadiz were split into two main groups: liberals and absolutists. The liberals, like Agustín Argüelles, were in charge. They worked to create a liberal state. They got rid of the old feudal system and the Inquisition. They also allowed freedom of the press and wrote the Constitution of 1812.

The word "liberal" itself came from these debates in Cadiz and then spread around the world.

The Cortes of the Trienio Liberal

In 1820, a military uprising forced King Ferdinand VII to bring back the 1812 Constitution. The Cortes met again in Madrid from 1820 to 1823. They were elected using the same rules as before, including representatives from Spanish America.

These Cortes had a short and troubled life. There were fights between different groups of liberals. The Cortes often held the real power, not fully trusting the king. This led to other European powers getting involved. They saw the king as a prisoner and sent an army to Spain to restore his absolute power. The Cortes had to flee Madrid and were eventually dissolved in 1823.

The Last Cortes of the Old System

The Cortes of Madrid of 1833 were the last ones called under the old rules. King Ferdinand VII called them to swear in his daughter Isabel (who would become Isabella II of Spain) as the future queen. This meeting showed a move towards more open politics.

Parliament during Isabella II's Reign

The Cortes of Madrid of 1834 began a new era of parliamentary life. This was during the First Carlist War. Power often switched between moderate and progressive liberals, usually after military uprisings. Only people with a certain amount of wealth could vote.

Spain had lost most of its colonies in America, so there were no longer deputies from those regions. A two-chamber system was set up, similar to the British Parliament. There was a lower chamber (the Congress of Deputies) and an upper chamber (the Senate).

In 1836, a new uprising led to the dissolution of the Cortes and the creation of a new constitution in 1837, which was more progressive.

The Cortes of 1840 passed the Law of Town Halls. In 1841-1843, the Cortes met under the regency of General Espartero. When he resigned, the Cortes declared the young Queen Isabella II, who was only 13, old enough to rule.

The Cortes of 1845, controlled by moderates, changed the constitution to be more conservative.

From 1845 to 1855, General Narváez's moderate party was mostly in power.

The progressives took control of the Cortes of 1854 after a revolution. They tried to write a new constitution, but it never became law.

From 1858 to 1866, the Liberal Union party was mostly in power. By 1867, the moderates had almost all the seats, which weakened the political system and led to more opposition.

The Cortes of the Sexenio Democrático

After the revolution of 1868, which sent Queen Isabella II into exile, the Cortes of 1869 wrote the Spanish Constitution of 1869. This constitution introduced universal male suffrage, meaning all men could vote.

The Cortes of 1872-1873 saw Spain become a republic (First Spanish Republic) after King Amadeus I stepped down. However, a military coup in 1874, led by General Pavía, violently broke into the Cortes and ended democratic life.

Later in 1874, another military uprising brought back the monarchy with Alfonso XII, Isabella II's son.

During these years, Emilio Castelar was a famous speaker in the Cortes.

Restoration Parliamentarism

After 1885, Spanish politics was known for turnism. This meant the two main parties, the Conservative Party and the Liberal-Progressive Party, took turns governing. When it was time for a change, the current government would resign. The king would then ask the opposition leader to form a new government. This new government would then call elections, which were often controlled to ensure they won. This system was called caciquism and involved local bosses influencing votes.

Many people criticized this system, especially after the disaster of 1898. People started talking about "regenerationism" to fix Spain's problems. However, turnism continued until 1917. The system finally ended with Primo de Rivera's military coup in 1923.

The Spanish Constitution of 1876 allowed for changes. For example, universal male suffrage was introduced in 1890. The abolition of slavery was also completed during this period (1880-1886), despite some opposition.

Most other political parties, like Carlists or Republicans, could not easily participate in this system. However, Pablo Iglesias (a socialist leader) won a seat in 1910. The Lliga Regionalista (a Catalan nationalist party) also had success in 1901. These successes happened in cities, where the caciquism system was weaker.

20th and 21st Centuries

The Primo de Rivera Dictatorship

General Primo de Rivera's dictatorship suspended the Constitution. He created a "pseudo-parliament" called the National Consultative Assembly from 1927 to 1930. It was not a true parliament because there were no real elections or multiple parties.

Parliament of the Second Republic

The Constituent Cortes elected in 1931 wrote the Spanish Constitution of 1931. This constitution created a single-chamber parliament called the Congress of Deputies. Many famous intellectuals and politicians were part of these Cortes, including José Ortega y Gasset and Manuel Azaña.

Debates were very important. For example, they debated whether regions should have the right to autonomy and whether women should be allowed to vote. The Cortes also had enough power to make the government fall if it lost their trust.

Later, in the Cortes of 1933 and Cortes of 1936, political groups became more and more divided. This led to the Spanish Civil War.

Spanish Civil War

During the Spanish Civil War, the Republican government and the Cortes moved from Madrid to Valencia. They held their last meeting in Spain in Figueres in February 1939.

On the other side, the rebel (Nationalist) side had no parliament. All political parties were banned or forced to join one group.

The Republican Courts in Exile

After the Civil War, some Republican leaders continued to hold symbolic Cortes meetings in exile outside Spain.

The Francoist Cortes

From 1942, the Cortes Españolas existed. These Cortes supported Franco's personal dictatorship. They were not a true parliament, but they gave the regime some institutional appearance.

Current Cortes

The 1977 elections were the first democratic elections after Franco's dictatorship. Many new politicians entered parliament. These Cortes worked to write the Spanish Constitution of 1978.

The debates for the 1978 Constitution were important, but the main political parties often reached agreements in private meetings. This led to a "consensus" on key issues.

Today, Spanish parliamentary life is often dominated by the government. Debates in Congress and Senate explain decisions already made by the government. The opposition can challenge the government through things like a motion of no confidence or during annual debates on the state of the nation.

There are two main national parties in Spain: the People's Party and the Spanish Socialist Workers' Party. There are also smaller parties, including those representing different regions of Spain.

A very important moment in this period was the attempted coup in 1981. Military officers stormed the Congress during a vote, but the coup failed.

The Senate is meant to be a second legislative chamber and represent the regions. There are often discussions about how to make it more effective. Spain also has nineteen regional parliaments, which have their own political debates.

See also

In Spanish: Parlamentarismo español para niños

In Spanish: Parlamentarismo español para niños

- Spanish nationalism

- Category:General elections in Spain

- President of the Congress of Deputies

- President of the Senate of Spain