Reign of Isabella II of Spain facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Kingdom of Spain

Reino de España

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1833–1868 | |||||||||

|

Anthem: Marcha Real

|

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

| Capital | Madrid | ||||||||

| Government | United parliamentary constitutional monarchy | ||||||||

| History | |||||||||

| 1833 | |||||||||

| 1868 | |||||||||

| ISO 3166 code | ES | ||||||||

|

|||||||||

The Reign of Isabella II of Spain was a very important time in the modern history of Spain. It lasted for over three decades. This period began in 1833 when King Ferdinand VII of Spain died. It ended in 1868 with the Glorious Revolution. This revolution forced Queen Isabella II of Spain to leave Spain and created a new liberal government.

When King Ferdinand VII died on September 29, 1833, his wife, María Cristina, became the regent. A regent is someone who rules for a child who is too young to be king or queen. María Cristina ruled for her daughter, Isabella II, with the help of liberal groups.

However, Ferdinand VII's brother, Carlos María Isidro de Borbón, wanted to be king. He claimed an old law called Salic law meant women could not rule. This law had actually been cancelled by Carlos IV and Ferdinand VII himself. This disagreement led to the First Carlist War, a civil war in Spain.

After María Cristina's regency, General Espartero briefly took over as regent. In 1843, when Isabella II was just thirteen years old, the Spanish parliament, called the Cortes Generales, decided she was old enough to rule on her own.

Isabella II's actual reign is usually split into four main parts:

- The moderate decade (1844–1854)

- The progressive biennium (1854–1856)

- The time of the Liberal Union governments (1856–1863)

- The final crisis (1863–1868)

During Isabella II's reign, Spain tried to become more modern. But there were many challenges. Different liberal groups argued among themselves. Some people still wanted an absolute monarchy, where the king or queen had all the power. Military leaders had a lot of influence over the government. Also, Spain faced economic problems. All these issues prevented Spain from fully changing from an old-style kingdom to a modern liberal state. This meant Spain was not as strong as other European countries by the late 1800s.

Queen Isabella herself was not very good at governing. She was often pressured by her family and powerful generals like Ramón María Narváez, Baldomero Espartero, and Leopoldo O'Donnell.

Isabella II's reign had two main parts:

- Her minority (1833–1843): During this time, her mother, Maria Christina of the Two Sicilies, and then General Baldomero Espartero, ruled for her.

- Her true reign (1843–1868): This began when the Cortes Generales declared her old enough to rule at age thirteen.

This period can be further divided:

- 1844–1854: The Moderate Decade (Década moderada). This was a time when the Moderate Party was in power.

- 1854–1856: The Progressive Two Years (Bienio progresista). This followed a period of unrest and saw the Progressive Party try to make reforms.

- 1856–1868: The Liberal Union period. A group called the Liberal Union government tried to find a middle ground between different political ideas.

- 1868: The crisis (La Gloriosa). This led to the downfall of Queen Isabella and her move to France.

Contents

The Regents: María Cristina and Espartero

The time when María Cristina ruled for her young daughter was marked by a civil war. This war was between those who supported Isabella II (called "Isabelinos" or "Cristinos") and those who supported Carlos María Isidro (called "Carlists").

Francisco Cea Bermúdez was the first head of government. He was very traditional, like the late King Ferdinand VII. Because he didn't allow enough liberal changes, he was replaced by Martínez de la Rosa. Martínez de la Rosa convinced María Cristina to create the Royal Statute of 1834. This was a step backward from the more liberal Constitution of Cadiz of 1812. It did not give power to the people.

When the traditional liberals failed, the more progressive liberals took power in 1835. A key figure was Juan Álvarez Mendizábal. He was a respected politician and money expert. He started many economic and political changes. One big change was taking away property from the Catholic Church. Later, under another progressive government, a new Constitution was approved in 1837. This tried to mix ideas from the Cadiz Constitution and find a balance between the traditional and progressive liberal parties.

The Carlist War caused big problems for Spain's economy and politics. Fighting against the Carlist army made the regent rely heavily on military leaders. One of these was General Espartero. He became very famous and helped win the war. The war ended with the Abrazo de Vergara (Embrace of Vergara).

In 1840, María Cristina tried to work with Espartero, but he sided with the progressives. A revolution broke out in Madrid on September 1. María Cristina was forced to leave Spain and hand over the regency to Espartero on October 12, 1840.

During his time as regent, General Espartero was accused of acting like a dictator. He mostly trusted military officers who thought like him. Meanwhile, traditional politicians like O'Donnell and Narváez kept trying to gain power. By 1843, even some liberals who had supported Espartero were working against him. On June 11, 1843, a revolt by the traditionalists, supported by some of Espartero's own men, forced him to leave power and go to London.

Isabella II's True Reign (1843–1868)

After Espartero's fall, political and military leaders decided not to have another regent. Instead, they declared Queen Isabella old enough to rule, even though she was only twelve. This began Isabella II's actual reign, which was a very complex time for Spain. It shaped much of the country's politics for the rest of the 19th century.

The declaration of Isabella's coming of age led to political confusion. The progressive leader, Joaquín María López, became head of government. He dissolved the Senate and called new elections, which was against the rules of the 1837 Constitution. He also appointed city officials to prevent Espartero's supporters from winning elections. He said he was doing this to save the country.

In September 1843, new elections were held. Traditionalists won more seats than progressives. The Cortes then approved that Isabella II would be declared of age when she turned 13 the next month. On November 10, 1843, she swore to uphold the 1837 Constitution. The government then resigned, and Salustiano de Olózaga, a progressive leader, was asked to form a new government.

Olózaga faced problems right away. His candidate for Congress president lost. Then, when he tried to pass a law about town councils, he asked the queen to dissolve the Cortes and call new elections. This led to the "Olózaga incident." Traditionalists accused him of forcing the queen to sign the decrees. Olózaga had to resign, even though he said he was innocent. The new president was the traditionalist Luis González Bravo.

González Bravo acted like a "civil dictator" for six months. He brought back the old Law of Town Councils to stop local groups from forming. He also ended the National Militia and created the Civil Guard, a national police force.

The elections in January 1844 were won by the traditionalists. This caused progressive uprisings in several provinces. Progressive leaders were arrested. In May, General Ramón María Narváez, the leader of the Moderate Party, became president. This began the period known as the Moderate Decade.

The Moderate Decade (1844–1854)

By spring 1844, Spain was considered peaceful. General Narváez became president again. He led a very strict government, treating his ministers like soldiers. Narváez pushed for political reforms, aiming to create a strong, central government. His team included Alejandro Mon, who reformed taxes, and Pedro José Pidal, who helped create the centralized state and an agreement with the Church in 1851.

The Moderate Party held power firmly with the Queen's support. In 1845, they decided to create a new constitution. They wanted to fix problems like the unhappy Carlists, the Church's loss of influence, and the constant changes in constitutions. The solution was the 1845 Constitution.

This new constitution created a constitutional monarchy where power was shared between the Crown and the Cortes (parliament). It allowed for special courts to try crimes against the government or Queen. It also declared Spain a confessional state, meaning Catholicism was the only official religion. The government agreed to financially support the Church. This helped to improve relations between the Church and the State, leading to the Concordat (agreement) in 1851.

The 1845 Constitution set up a two-house parliament: the Senate and the Congress. Elections were held every five years. Only a small percentage of the population (less than 1%) could vote, as voters had to meet certain income requirements.

During this period, the Moderates tried to undo some liberal changes from earlier times. They passed a new municipal law in 1845 that gave the central government more control over local councils. They also passed laws that made the government more centralized, controlling town councils and universities.

However, the Moderate Party soon began to split, causing political instability. Narváez was dismissed in 1846, partly because of the Queen's difficult marriage arrangements. On October 10, 1846, Isabella married her cousin, Francisco de Asís de Borbón. Other European powers, especially England, were worried about Spain's royal marriages. They wanted to prevent Spain and France from being united under one ruler.

After Narváez, several governments came and went quickly. The Carlists continued to cause trouble. In October 1847, Narváez became president again. He appointed Bravo Murillo as his main helper. This new government was stable until the Revolutions of 1848, which spread across Europe. These revolutions, led by workers and more liberal groups, caused uprisings in Spain. Narváez put them down harshly. He also broke off diplomatic ties with Great Britain, believing they were helping the Carlists. Narváez acted like a dictator until he was forced to resign in January 1851 and was replaced by Bravo Murillo.

Once in power, Bravo Murillo tried to fix relations with the Catholic Church. He signed the Concordat in 1851 with Pope Pius IX. This agreement protected Church property and stopped the sale of Church lands. It also stated that Catholicism was the only religion in Spain.

In December 1851, Louis Bonaparte, who became Napoleon III, took power in France. This affected Spain. Bravo Murillo closed the Cortes (parliament) for a year and ruled by decree. He tried to create a political system that gave more power to the Crown. This caused a strong reaction, and people demanded the Cortes be reopened. When they reopened in December 1852, a new president was appointed. Bravo Murillo tried to create a new, more absolute constitution, but it was rejected. He was forced to resign.

These political events led to armed conflict. A group of senators and congressmen tried to find a peaceful solution, but they were ignored. In February 1854, an uprising in Zaragoza was put down, but the plotting continued. The next uprising happened in Vicálvaro, known as "La Vicalvarada." Generals O'Donnell and Dulce led it. They gained more support in Manzanares, where General Serrano joined them. They issued the Manzanares Manifesto, which led to major political change and uprisings across Spain. The government resigned, and a new governing council was formed in Madrid. The Queen was forced to appoint a new government. Surprisingly, she chose Espartero as head of government, with O'Donnell as Minister of War.

The Progressive Biennium (1854–1856)

During Bravo Murillo's government, there was a lot of corruption. This was due to fast economic growth and people trying to get special favors in public projects. Even the royal family was involved. Bravo Murillo resigned in 1852, and three more governments followed until July 1854. Meanwhile, Leopoldo O'Donnell, who had worked with the former Regent María Cristina, joined the more liberal traditionalists. He planned an uprising with other officers.

On June 28, O'Donnell and his forces clashed with government troops at Vicálvaro. This event, called La Vicalvarada, had no clear winner. But throughout June and July, more troops joined the uprising. On July 17, in Madrid, civilians and soldiers protested violently. The Queen's mother, María Cristina, had to seek safety. The protests led to the victory of the rebels.

After some desperate attempts to control the riots, the Queen finally gave in. Following her mother's advice, she appointed Espartero as president. This marked the start of the Progressive Biennium.

On July 28, 1854, Espartero and O'Donnell entered Madrid as heroes. Espartero had to appoint O'Donnell as war minister because O'Donnell was popular and controlled many military groups. Although they seemed to work together, there were problems. O'Donnell tried to stop Espartero's progressive ideas about the Church and land sales. Espartero, influenced by his own beliefs and changes in Europe, wanted Spain to become more liberal.

This period was a mix of "left-wing" traditionalists and "right-wing" progressives. Progressive laws were brought back, like those for town councils and the Militia. A new constitution was written, but it was never officially put into law. The main focus of this period was economic reforms to help the middle class. Important economic measures included Madoz's land sales and the railway law.

The new land sales affected property owned by local councils, and to a lesser extent, the Church and charities. Much more land was taken over by the state than in 1837. The goals were to improve the government's finances and pay for railway construction. This had serious consequences for town councils, as they lost a major source of income.

The Railway Law was passed in 1855 to organize the building of the railway network and attract investors. Spain didn't have many big investors, so foreign money was used. Also, the trains and tracks came from England. The railway track width in Spain was different from the rest of Europe, which caused problems. The railway did not become as successful as expected.

Social unrest also grew. There were uprisings in Barcelona against forced military service, low wages, and long working hours. The government responded by making some improvements for workers and allowing them to form associations. The final crisis came in 1856, with many uprisings that forced Espartero to resign. The Queen then appointed O'Donnell as head of government.

The Progressive Biennium ended when Espartero and O'Donnell finally broke apart. O'Donnell had been secretly working on forming the Liberal Union while in government with Espartero. The elections in 1854 had given O'Donnell's supporters more seats than Espartero's. Their cooperation fell apart over the land sales and religious issues. A proposal to allow freedom of belief was approved, which broke relations with the Pope. O'Donnell did not want this to continue. Espartero tried to defend liberal ideas by mobilizing the National Militia and the press against the traditionalist ministers. But the Queen preferred O'Donnell to lead during this unstable time, which also included Carlist uprisings and a serious economic situation. The two sides clashed in the streets on July 14 and 15, 1856, and Espartero chose to withdraw.

Moderate Rule and Liberal Union Governments (1856–1863)

Once O'Donnell became president, he brought back the 1845 Constitution. He added an extra law to try and attract more liberal groups. But arguments between different traditionalist and liberal groups continued. After the events of July, O'Donnell's power weakened. The Queen changed the government again, bringing Narváez back on October 12, 1856. Instability continued, and several other leaders briefly held the presidency.

O'Donnell's return marked the start of a long period of Liberal Union governments. On June 30, 1858, O'Donnell formed a government where he also served as Minister of War. This government lasted for four and a half years, until January 17, 1863. It was the most stable government of the time. Key members included Pedro Salaverría, who managed the economy, and José de Posada Herrera, who skillfully controlled elections.

The 1845 Constitution was re-established. Elections in September 1858 gave the Liberal Union full control of the parliament. The government made major investments in public works, like railways, and improved the army. They continued selling off Church lands, but the State gave the Church government bonds in return and brought back the 1851 Concordat. Several important laws were passed, including the Mortgage Law (1861) and the first Road Plan. However, the government failed to stop political and economic corruption.

Carlist Uprisings and Peasant Revolts

In 1860, there was a failed Carlist attempt to start a new war. The Carlist leader, Carlos Luis de Borbón y Braganza, tried to land troops near Tarragona, but it was a complete failure. There was also a peasant uprising in Loja, led by Rafael Pérez del Álamo. This was a major movement by farmers demanding land and work. It was quickly put down, and many people were sentenced to death.

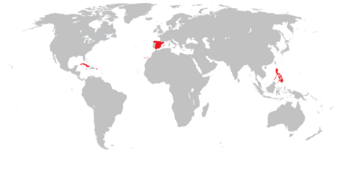

Foreign Policy

During the Liberal Union governments, Spain engaged in foreign policy actions to boost its image. These actions were popular with the public. Spain joined a French-Spanish expedition to Cochinchina (part of modern Vietnam) from 1857 to 1862. It also took part in the Crimean War. In the African War of 1859, O'Donnell gained popularity by securing the Spanish cities of Ceuta and Melilla. Spain also joined an expedition to Mexico, annexed Santo Domingo in 1861, and fought in the First Pacific War in 1863.

These actions were an attempt to stop Spain's decline as a colonial power. Spain had lost most of its South American colonies and its role in Europe had shrunk. Meanwhile, France and Britain had strong empires.

Spain's foreign policy during Isabella's reign was often unclear. The country lacked a modern army to support its interests around the world. Queen Isabella herself didn't know much about international politics. Also, France and Great Britain were much stronger militarily and economically.

In Europe, the situation had changed. Britain and France, once rivals, were now allies and supported Isabella II's rule. Countries like Prussia, Austria, and Russia supported the Carlists. Spain joined the Quadruple Alliance of 1834 with Portugal, France, and Britain. This meant France and Britain supported Isabella's monarchy as long as Spain followed their agreed foreign policy.

The Fall of the Liberal Union Government

By 1861, O'Donnell's government faced increasing criticism from the Moderate and Progressive parties. Important figures like Cánovas and General Juan Prim left the Liberal Union due to disagreements. They felt the government had betrayed its original ideas. Members of the army and the Catalan business class also joined the opposition. Disagreements within the government continued. On March 2, 1863, the Queen accepted O'Donnell's resignation.

Final Crisis of the Reign (1863–1868)

After the Progressive Biennium, the 1845 Constitution was re-established, and the Liberal Union stayed in power under O'Donnell (1856–1863). Narváez returned during a calmer period, establishing a centralized state and stopping the land sales. Foreign policy was used to distract people from internal problems. Spain got involved in conflicts in Morocco, Indochina, and Mexico.

In 1863, a group of progressives, democrats, and republicans won elections. However, Narváez came to power with a very strict government that lasted until 1868. That year, a new revolution broke out against the government and Queen Isabella II: the Glorious Revolution.

Replacing O'Donnell was difficult. The traditional parties had many internal problems. The traditionalists, led by General Fernando Fernández de Córdova, offered to form a government. The progressives decided to withdraw from politics. In the end, the Queen gave the government to Manuel Pando Fernández de Pineda, who had little support. His presidency lasted only until January 1864. Seven other governments followed until the revolution of 1868.

Narváez formed a government on September 16, 1864. He wanted to unite different groups and bring the progressives back into active politics. He feared that people would question the Queen's rule even more. But the progressives refused to join a system they saw as corrupt. This led Narváez to become more strict.

A major event that damaged the government's reputation was the Night of St. Daniel on April 10, 1865. University students in Madrid protested against new rules that limited free thinking in classrooms. They also protested against the firing of Emilio Castelar, a professor, for writing articles that criticized the Queen for taking 25% of the money from the sale of royal property. The government responded harshly, and thirteen students were killed.

This crisis led to a new government on June 21, with O'Donnell, Cánovas, and others returning. A new law was passed that doubled the number of voters to 400,000. Elections were called, but the progressives refused to participate. General Prim then led a revolt in Villarejo de Salvanés, trying to seize power by force, but it failed. O'Donnell became even stricter. This led to another uprising at the San Gil Barracks on June 22, again organized by Prim. This also failed and resulted in many deaths and over sixty people sentenced to death.

O'Donnell retired from politics, exhausted. On July 10, Narváez replaced him. Narváez pardoned some rebels but continued with strict rules. He expelled republicans and professors who promoted free thinking. He also increased censorship and strengthened public order. When Narváez died on April 23, 1868, the strict Luis González Bravo took over. But the revolution was already planned. On September 19, the "La Gloriosa" revolution began with the cry, "Down with the Bourbons! Long live Spain with honor!" Isabella II went into exile, and a new democratic period began in Spain.

Creating the Centralized State

The idea of a centralized state was a big contribution from the Moderates. It lasted for a very long time in Spain. This centralized state was not part of the 1845 Constitution. Instead, it was created through special laws. The main person behind this was Pedro José Pidal. He copied the model of centralization that Napoleon had used in France.

In this system, the government is controlled by single leaders at different levels. In Spain, the Queen and the head of government were at the top. Below them were the civil governors, who were in charge of the provinces and appointed by the central government. Finally, there were the mayors, town councils, and local groups. These were appointed by the civil governors, though in big cities, the central government appointed the mayors directly.

In the centralized Spanish state, provincial councils, which used to have a lot of power, became only advisory bodies. The civil governor's main support was the provincial council, which acted as a court for legal and administrative issues. Within the town councils, all members were elected by voters who met certain income requirements. They had to be approved by the mayor and the civil governor. The mayor had to maintain public order and follow the central government's rules. Sometimes, the central government would appoint a Corregidor instead of an elected mayor.

See also

In Spanish: Reinado de Isabel II de España para niños

In Spanish: Reinado de Isabel II de España para niños