Sweet Track facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Sweet Track |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Location | Shapwick Heath, Somerset Levels, England |

| Built | 3807 or 3806 BC |

| Designated | 13 June 1996 |

| Reference no. | 27978 (was Somerset 399) |

| Designated | 22 April 1996 |

| Reference no. | 27979 (was Somerset 400) |

| Lua error in Module:Location_map at line 420: attempt to index field 'wikibase' (a nil value). | |

The Sweet Track is an amazing old wooden path or bridge found in the Somerset Levels, England. It's named after Ray Sweet, who discovered it. This path was built way back in 3807 BC, which means it's over 5,800 years old! It's one of the oldest wooden paths ever found in the British Isles, dating back to the New Stone Age. We now know that the Sweet Track was mostly built on top of an even older path called the Post Track.

This ancient path stretched for about 2,000 meters (or 1.2 miles) across a marshy area. It connected what was once an island at Westhay to higher ground at Shapwick. The Sweet Track is just one of many paths that used to cross the Somerset Levels. Many cool ancient items, like a special ceremonial axe head made of a green stone called jadeitite, have been found in the muddy peat bogs along the path.

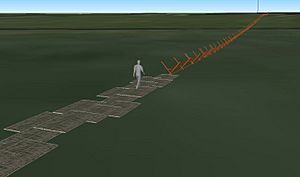

The path was made from wooden poles pushed into the wet ground. These poles held up a walkway made mostly of oak planks laid end-to-end. The Sweet Track was used for only about ten years. It was then left behind, probably because the water levels in the marsh got too high. When it was found in 1970, most of the path was left where it was. Special efforts are being made to keep the wood wet and preserved. Some parts of the track are stored in the British Museum and the Museum of Somerset in Taunton. You can even walk on a rebuilt section of the path at the Shapwick Heath National Nature Reserve, right where the original path once stood!

Contents

Where is the Sweet Track Located?

Around 4,000 BC, the Sweet Track was built to connect an island at Westhay with higher ground at Shapwick. This area is close to the River Brue. At Westhay, there are old mounds that show where ancient homes, like lake villages, once stood. These homes were probably similar to the Glastonbury Lake Village from the Iron Age. That village was built on a swampy area using a base of timber, brushwood, and clay.

Other old wooden paths have been found nearby. These include the Honeygore, Abbotts Way, Bells, Bakers, Westhay, and Nidons trackways. They all helped people travel more easily between settlements in the peat bog. Places like the nearby Meare Pool show that these paths were important for getting around. Meare Pool was formed as peat bogs grew around it. Studies show the pool is filled with at least 2 meters (6.6 feet) of mud and plant remains.

The two Meare Lake Villages found within Meare Pool seem to have started as simple shelters built on dry peat. These might have been tents or animal pens. Later, people spread clay over the peat to create raised areas for living, working, and moving around. In some spots, thicker clay was used to build hearths for fires.

How Was the Sweet Track Discovered and Studied?

The Sweet Track was found in 1970 by Ray Sweet during peat digging. Ray worked for a company called E. J. Godwin. They sent a piece of the path to John Coles, an archaeology expert at Cambridge University. He was already studying other nearby ancient paths. Coles' interest led to the Somerset Levels Project, which ran from 1973 to 1989. This project, supported by groups like English Heritage, studied many ancient sites in the area. It helped us understand how important these paths were for trade and travel thousands of years ago. John Coles, Bryony Coles, and the Somerset Levels Project won awards for their amazing work, including the European Archaeological Heritage Prize in 2006.

Scientists used Dendrochronology (tree-ring dating) to figure out the exact age of the wood. This showed the track was built in 3807 BC. For a while, people thought the Sweet Track was the oldest road in the world! But then, in 2009, an even older path from 4100 BC was found in Plumstead, near Belmarsh prison. Studying the Sweet Track's wood has also helped scientists learn more about tree-ring patterns from the New Stone Age. Comparing it with wood from other places helped create a better map of ancient climates.

The wood from the track is now called bog-wood. This is wood that has been buried in peat bogs for a very long time, sometimes thousands of years. The acidic and oxygen-free conditions in the bog stop the wood from rotting. Bog-wood often turns brown because of natural dyes called tannins in the water. It's like an early stage of turning into a fossil. Because the track was so old, large-scale digs started in 1973, funded by the government.

What Items Were Found Near the Track?

In 1973, a special jadeitite axe head was found next to the track. People think it might have been left there as an offering. This axe head is one of over 100 similar ones found in Britain and Ireland. It's in great condition, and the material is very valuable. This suggests it was a symbolic axe, not one used for cutting wood. It was very hard to work with this stone, which came from the Alps in Europe. So, all these axe heads found in Britain were probably not used for everyday tasks. They might have been a form of money or special gifts. Radiocarbon dating of the peat around the axe head shows it was placed there around 3200 BC.

Many wooden items were found at the site, including paddles, a dish, arrow shafts, parts of four hazel bows, a throwing axe, yew pins, digging sticks, a mattock, a comb, toggles, and a spoon piece. Other items found were flint flakes, arrowheads, and a perfectly preserved chipped flint axe.

In 2008, a geophysical survey was done in the area. The results from the magnetometer were unclear. It's possible the wood affects how water and minerals move through the peat.

Who Built the Sweet Track?

The people who built the Sweet Track were New Stone Age farmers. They had settled in the area around 3900 BC. The evidence suggests they were well-organized and had settled down by the time they built the path. Before these people arrived, the higher lands around the marsh were covered in thick forests. But the local people started clearing these forests to make space for farming, mostly raising cattle and sheep, with some crops.

In winter, the flooded areas of the marsh would have given these communities plenty of fish and wild birds. In summer, the drier areas offered rich grasslands for grazing cattle and sheep. There were also reeds, wood, and timber for building, plus lots of wild animals, birds, fruit, and seeds. The need to reach the islands in the bog was so important that they worked together to gather all the timber and build the path. They probably did this when the water levels were lowest after a dry spell. The huge amount of work needed to build the track shows they were skilled woodworkers. It also suggests that some people had special jobs among the workers. They also seemed to be managing the nearby forests for at least 120 years.

How Was the Sweet Track Constructed?

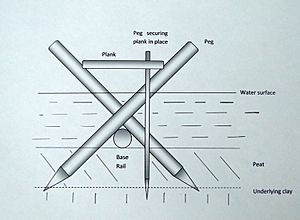

The Sweet Track was built in 3807 or 3806 BC. It was a walkway made mostly of oak planks laid end-to-end. These planks were held up by crossed pegs made of ash, oak, and lime wood. The pegs were pushed into the soft peat below. The planks were up to 40 centimeters (16 inches) wide, 3 meters (9.8 feet) long, and less than 5 centimeters (2 inches) thick. They were cut from trees that were up to 400 years old and 1 meter (3.3 feet) across! These trees were cut down and split using only stone axes, wooden wedges, and mallets. The long, straight pegs with no branches suggest they came from coppiced woodland, where trees are cut back to grow new straight shoots.

Long wooden rails, up to 6.1 meters (20 feet) long and 7.6 centimeters (3 inches) thick, were laid down. These were mostly made of hazel and alder. The pegs were driven at an angle across these rails and into the peat. Notches were then cut into the planks to fit over the pegs, and the planks were laid along the X-shapes to form the walkway. In some places, a second rail was put on top of the first to make the plank level with the rest of the path. Some planks were made stable with thin, vertical wooden pegs pushed through holes near the end of the planks and into the peat or clay below. At the southern end, smaller trees were used, and the planks were split across the grain to use the whole tree trunk. Pieces of other trees like holly, willow, poplar, dogwood, ivy, birch, and apple were also found.

Because the area was so wet, the parts of the track must have been made somewhere else and then brought to the site. However, wood chips and cut branches show that some trimming was done right there. The track was built using about 200,000 kilograms (440,000 pounds) of timber. Experts believe that once the materials were on site, ten men could have put it together in just one day!

The Sweet Track was only used for about ten years. Rising water levels probably covered it, making it unusable. The different items found along the track suggest it was used daily by the farming community. Since its discovery, we've learned that parts of the Sweet Track were built along an even older path, the Post Track, which was made thirty years earlier in 3838 BC.

How is the Sweet Track Being Preserved?

Most of the Sweet Track is still in its original place. This area is now part of the Shapwick Heath biological Site of Special Scientific Interest and National Nature Reserve. After land was bought by the National Heritage Memorial Fund, a system was put in place to pump and spread water along a 500-meter (1,600 feet) section. This helps keep the wood wet and preserved. This way of saving ancient wetland remains, by keeping the water level high, is quite rare. A 500-meter section, owned by the Nature Conservancy Council, has a clay bank around it to stop water from draining into lower peat fields. Water levels are checked regularly.

This method works well! For example, the nearby Abbot's Way, which didn't get this treatment, was found to be dry and crumbling in 1996. The Nature Conservancy Council, the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs, and the Somerset Levels Project all work together to check and maintain water levels in the Shapwick Heath Nature Reserve.

Even though the wood found from the Levels looked whole, it was very soft and damaged inside. Where possible, good pieces of wood or the shaped ends of pegs were taken away to be preserved for study. The preservation process involved putting the wood in heated tanks with a solution called polyethylene glycol. Over about nine months, the water in the wood was slowly replaced with this wax-like substance through evaporation. After this, the wood was taken out, cleaned, and as the wax cooled and hardened, the artifact became firm and could be handled.

A section of the track from land owned by Fisons (a company that dug for peat) was given to the British Museum in London. This short section can be put together for display, but it's currently stored safely off-site in special controlled conditions. A rebuilt section was shown at the Peat Moors Centre near Glastonbury. This center was closed in October 2009 due to budget cuts. The main exhibits are still there, but it's not clear when the public will be able to see them again. Other pieces of the track are kept at the Museum of Somerset.

Parts of the track have been named a scheduled monument. This means it's a "nationally important" historic structure and archaeological site that is protected from any changes without permission. These sections are also on Historic England's Heritage at Risk Register.

Images for kids

| William M. Jackson |

| Juan E. Gilbert |

| Neil deGrasse Tyson |