Tacfarinas facts for kids

Tacfarinas (his Roman name, from the Berber Tikfarin or Takfarin; died AD 24) was a Numidian Berber leader from Thagaste in what is now Algeria. He had once been a soldier in the Roman army but left. Tacfarinas then led his own Musulamii tribe and other Berber tribes in a war against the Romans in North Africa. This happened during the rule of Emperor Tiberius (AD 14–37).

We don't know exactly why Tacfarinas started fighting. But it was likely because the Romans, under Emperor Augustus, took over land that the Musulamii tribe traditionally used for their animals. Tacfarinas's large attacks caused big problems for the province's grain farms. This also threatened to cause trouble in Rome itself, as the city relied on this grain.

The Romans found it hard to defeat Tacfarinas because his Numidian fighters could move very quickly. They also had support from many desert tribes. Finally, in AD 24, the Romans caught and killed Tacfarinas.

After the war, the Romans took control of the entire Tunisian plateau. They turned it into farmland, mostly for growing wheat. The Musulamii and other nomadic tribes probably lost their summer grazing lands forever. They were forced to live a harder life in the Aurès mountains and dry areas. This conflict also likely led to the Roman takeover of the kingdom of Mauretania in AD 44.

Contents

What Was North Africa Like?

Berber People and Their Lands

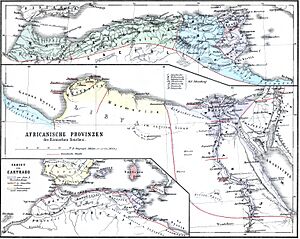

In Roman times, the native people of North Africa (the Maghreb) were called different names. These included the Libyae, the Afri (in modern Tunisia, where the name Africa comes from), the Numidians (eastern Algeria), and the Mauri (western Algeria and Morocco).

North of the Atlas Mountains, the land was rich and had plenty of water. People living here usually stayed in one place. But on the southern edges, tribes lived a semi-nomadic life. They raised herds of cattle, sheep, and goats. They moved their animals between summer grazing lands on the central plateau of Tunisia and the Aurès mountains, and winter lands around salt lakes (chotts) in the desert. These tribes included the Gaetuli, Musulamii, and Garamantes.

The Roman Province of Africa

The Roman province of Africa Vetus ("Old Africa") was once the land of Carthage. Rome took control of it after defeating Carthage in 146 BC. This land was very fertile, even more so than today. It had many people (about 1.5 million) and was Rome's most important source of grain by 50 BC. It was said that Africa fed the city of Rome for eight months of the year.

This province had huge farms called latifundia. These were owned by rich Romans who didn't even live there. The Roman writer Pliny the Elder said that half of all farmland in the province was owned by just six Roman senators. The rest of northwest Africa was made up of two Berber kingdoms allied with Rome: Numidia and Mauretania.

In 45 BC, the Roman leader Julius Caesar defeated King Juba I of Numidia. He added Numidia to the Roman province, calling it Africa Nova ("New Africa"). This meant the old Numidian royal family, who had been loyal to Rome, lost their kingdom. King Juba's young son, Juba II, grew up in Rome and became a close friend of Augustus, who later became emperor.

In 25 BC, Augustus changed things. He made Juba II king of Mauretania and added the southern parts of Africa Nova to his kingdom. So Juba ruled a huge area. Augustus hoped Juba's warriors would protect the Roman province from desert tribes. But Juba couldn't do this well. The independent desert tribes didn't respect him, seeing him as a Roman puppet.

Fighting with Nomadic Tribes

The Romans kept the most fertile part of Numidia for their province. This included the central Tunisian plateau, which was perfect for growing wheat. Rome needed more and more grain. This area, about 27,000 square kilometers, could double the province's grain production.

The Roman army's main unit in Africa, the III Augusta, was placed at Theveste (modern Tébessa, Algeria). This was to protect the plateau from attacks. Later, during Tacfarinas's war, the legion's base moved to Ammaedara (modern Haïdra, Tunisia), right in the middle of the plateau. The Romans also built new roads. Along with this building, they fenced off land to turn it from grazing areas into wheat fields. They also tried to stop nomadic tribes from moving into the province.

The Tunisian plateau was the traditional summer grazing land for the semi-nomadic Musulamii and Gaetuli tribes. The Roman takeover of this land led to long and bitter fights between the nomads and Rome during Augustus's rule. Roman governors fought many campaigns against the nomads. After AD 6, there were no more big wars, but smaller, ongoing fights against Roman rule continued. Tacfarinas grew up during this time of conflict.

However, not all desert tribes were enemies of Rome. Many nomads joined the Roman army. This gave them a good career and a chance to use their fighting skills, which Romans respected. Numidian cavalry (horsemen) were known as the best light cavalry in the Roman world. They rode small, fast desert horses without saddles or stirrups, using only a rope around the neck. They were lightly armored, with only a small shield. Their weapons were javelins. These horsemen were very fast and good at quick attacks, throwing javelins, and then riding away before enemies could catch them. They were excellent for scouting, ambushing, and chasing enemies. Numidian foot soldiers were also light and fast. But both Numidian horse and foot soldiers were vulnerable in close combat against Roman troops, who wore metal armor.

Tacfarinas's Early Life

We don't know much about Tacfarinas's family or early life. He was probably a member of the Musulamii tribe and not from a royal or noble family. When he was old enough (around 20), he joined a Roman auxiliary regiment. We don't know if he volunteered or was forced to join, or if he was a cavalry or infantry soldier. He served for several years.

Tacfarinas Fights Rome

Camillus as Governor (AD 15–17)

At some point, Tacfarinas left the Roman army. He gathered a group of raiders and attacked Roman lands. Using his knowledge of the Roman military, he organized his growing group into proper units. Soon, he had an effective fighting force. The different Musulamii clans accepted him as their main leader.

Tacfarinas quickly gained support from some of the Mauri, who lived west of the Musulamii. A leader named Mazippa brought many Mauri to join Tacfarinas. The Cinithii tribe, living in Roman territory in southern Tunisia, also joined him. Tacfarinas trained some of his men to fight like Romans, while Mazippa led his traditional light Mauri horsemen on destructive raids deep into Roman lands.

By AD 17, the Roman governor of Africa, Marcus Furius Camillus, faced a serious problem. This was much more than just usual border raids. Tacfarinas relied on quick attacks and retreats. Camillus's forces (about 10,000 men) were outnumbered by Tacfarinas's followers. But Camillus decided to use the Roman advantages in armor and training. He offered Tacfarinas a big battle. Tacfarinas felt confident with his larger army, which combined Roman and Numidian fighting styles. But his army was completely defeated. Tacfarinas fled into the desert with what was left of his forces. Camillus was honored for his victory.

Apronius as Governor (AD 18–20)

The Romans were wrong to think the war was over. Tacfarinas was a tough and determined enemy. For the next seven years, he fought a devastating war against the Roman province. Neither side could win a final victory. Tacfarinas couldn't defeat the Romans in big battles or sieges. The Romans couldn't catch such a mobile enemy. Tacfarinas could always disappear into the desert or mountains, where the Romans couldn't reach him.

Meanwhile, Tacfarinas's raids caused huge economic damage. It's likely that the high grain prices in Rome during this time were due to his attacks. These high prices even caused riots in Rome in AD 19.

In AD 18, Lucius Apronius replaced Camillus as governor. Tacfarinas launched quick raids, destroying villages and disappearing before Roman forces could arrive. Growing bolder, Tacfarinas tried to besiege a Roman fort on the river Pagyda. A Roman commander named Decrius thought it was shameful for Roman soldiers to be trapped by "deserters and tramps." He ordered his troops to attack the besiegers, but they were forced back. Decrius, even after being hit by arrows, rushed at the enemy. But his men retreated into the fort as their commander fell.

Roman soldiers were not allowed to retreat unless ordered. When Apronius heard about this, he ordered the unit to be decimated for cowardice. This meant every tenth man, chosen by lot, was beaten to death in front of his comrades. This harsh punishment "had a good effect," according to the historian Tacitus. At the next fort attacked by Tacfarinas, Thala, the small group of 500 old soldiers successfully fought off the attackers.

The defeat at Thala showed Tacfarinas that he couldn't fight the Romans in big battles. So he went back to guerrilla tactics. He would retreat when Romans advanced, then attack their supply lines from behind. The Romans became tired and frustrated. Eventually, Tacfarinas had so much loot that he needed a more stable base. He set up camp near the Mediterranean coast in Mauretania. Here, a fast-moving group of Roman cavalry and light-armed soldiers, led by Apronius's son, surprised him. Tacfarinas had to flee into the Aurès mountains, leaving most of his loot behind. For this, Apronius (the father) also received honors.

Blaesus as Governor (AD 21–23)

At this point, Tacfarinas sent messengers to Rome. He offered peace if he and his followers were given land in the province. He probably wanted access to their traditional grazing grounds again. Tacfarinas warned that if his demands weren't met, he would fight forever. Emperor Tiberius was furious. He thought it was outrageous that a "deserter and common bandit" would demand terms like a foreign king. The offer was refused, and Tacfarinas started fighting again.

Tiberius demanded that the Roman Senate appoint a very experienced general to Africa to deal with Tacfarinas once and for all. The chosen man was Quintus Junius Blaesus. He was a veteran general and the uncle of Sejanus, Tiberius's trusted advisor. Tiberius gave Blaesus an extra legion (the IX Hispana) and its supporting troops. This doubled the Roman force in Africa to about 20,000 men. He also allowed Blaesus to offer a pardon to any of Tacfarinas's allies who surrendered. But Tacfarinas himself was to be captured or killed at all costs.

Blaesus offered the amnesty, and many of Tacfarinas's tired allies accepted it. The new governor also used new tactics. With more troops, he could cover Tacfarinas's routes into the province better. He divided his forces into three groups covering different areas. He built many new, small forts, each holding only about 80 soldiers. These forts were manned all year round, not just during fighting season. From these forts, small, fast units of desert-trained troops would go out and keep Tacfarinas's groups under constant pressure. This system almost stopped Tacfarinas's raids.

Blaesus's campaign had its biggest success in AD 22 when his men captured Tacfarinas's brother. After this, Blaesus moved his troops back to their usual winter camps. Tiberius thought this meant the war was over. He gave Blaesus the special title of imperator ("victorious general"). This was the last time someone outside the emperor's family received this title. When Blaesus returned to Rome in AD 23, he also received honors. The emperor then ordered the 9th legion to leave Africa, believing it was no longer needed. But Tacitus, the historian, thought Blaesus and Tiberius were too optimistic, as Tacfarinas was still free with many followers.

Final Defeat (AD 24)

The Romans soon realized they were wrong. The new governor, Publius Cornelius Dolabella, who arrived in AD 24, faced a threat as serious as any before him. Tacfarinas's strength was that there were always new raiders among the desert tribes. So even if he lost many men, he could quickly rebuild his groups.

Tacfarinas now started saying he was leading a war to free his people. He used the news of half the Roman army leaving to spread rumors that the Roman Empire was falling apart. He claimed that the remaining Roman soldiers could be defeated, and Numidia could be free forever if all Numidians worked together. His message worked very well. Many Mauri warriors joined him, turning against their young pro-Roman king, Ptolemy, who had just become king after his father, Juba II. Also, many poor farmers joined the rebels. Tacfarinas also received secret help from the king of the Garamantes. This king was officially allied with Rome, but he made a lot of money from Tacfarinas's stolen goods and didn't stop his warriors from joining the rebels. Given the emergency, Dolabella could have asked to keep the 9th legion, but he didn't dare to tell Tiberius the bad news.

By the start of the AD 24 fighting season, Tacfarinas felt strong enough to besiege the Roman fort of Thubursicum. Dolabella quickly gathered all his available troops and rushed to lift the siege. Again, the Numidians couldn't stand against the Roman infantry charge. They were defeated in the first attack and fled west into Mauretania.

Dolabella then began a full effort to hunt down Tacfarinas. It was clear the rebellion wouldn't end until its leader was gone. The governor asked for help from King Ptolemy, whose kingdom Tacfarinas had fled to. Ptolemy sent many loyal Mauri horsemen. With these extra troops, Dolabella divided his force into four groups moving side-by-side to cover as much land as possible. The allied cavalry acted as scouts between the main groups.

These tactics soon worked. They got important information that Tacfarinas had set up camp near the ruined fort of Auzea. This was far west of the Roman province, surrounded by thick forests. Tacfarinas probably thought the Romans wouldn't find him there, as he didn't even post guards in the woods.

Like a raid four years earlier, Dolabella immediately sent a fast strike force of light-armed infantry and Numidian cavalry. They approached Tacfarinas's camp without being seen, hidden by the woods and the darkness before dawn. At dawn, many Numidians were still asleep and unarmed, and their horses were grazing far away. They were woken up by the sound of Roman trumpets. The Romans attacked the camp in full battle order. The disorganized Numidians scrambled to find their weapons and horses. The complete surprise led to a massacre. The Romans were eager for revenge after years of hardship. Roman officers directed their men to find Tacfarinas himself. Tacfarinas and his guards were quickly surrounded. In a fierce fight, his bodyguards were killed, and his son was captured. Realizing there was no escape this time, Tacfarinas took his own life.

What Happened After?

Tacfarinas's death ended the Musulamii's hopes of stopping the Romans from taking their grazing lands. Dolabella immediately started surveying the entire plateau for tax purposes after Tacfarinas died. This was finished by AD 29/30. Stone markers laid by Roman surveyors still exist today, reaching as far as the Chott el Jerid on the province's southern border. The region was mostly turned into grain farms. The Musulamii and other tribes likely lost their former grazing areas forever.

Dolabella asked the Senate for honors for his victory. But his request was denied by Tiberius. This was surprising because Dolabella had actually ended the war by killing Tacfarinas, unlike his three predecessors. The historian Tacitus suggests that Tiberius's advisor, Sejanus, didn't want anyone else to get too much glory. Also, Tiberius was probably embarrassed that the war had started again after he had declared it won.

The Garamantes, fearing that their secret support for Tacfarinas had been found out, sent messengers to Rome to declare their loyalty. We don't know how successful they were. Ptolemy, king of Mauretania, was rewarded for his loyalty. He was given the title rex, socius et amicus populi Romani ("king, ally and friend of the Roman people"). This meant he was a puppet-king. As a special honor, an old Roman ceremony was brought back. A Roman senator traveled to Ptolemy's capital with gifts: an ivory baton and a special purple toga with gold embroidery.

Ironically, that same toga led to Ptolemy's downfall, according to the Roman historian Suetonius. Many years later, in AD 40, Ptolemy wore it during a visit to Rome as a guest of Emperor Caligula. When they entered the arena together, the crowd admired the toga and Ptolemy greatly. In a fit of jealousy, the emperor ordered Ptolemy's immediate execution. Beyond this simple explanation, it's likely that the Roman government was worried about Ptolemy's growing wealth and independence. He had started making gold coins, which was usually only done by independent rulers. His family background also made him very popular in North Africa. On his father's side, he was a descendant of the ancient Numidian king Massinissa. On his mother's side, he was the grandson of Mark Antony and Cleopatra, the last pharaoh of independent Egypt. The Roman leaders must have worried that if Ptolemy ever turned against Rome, his background, wealth, and power could threaten all of Rome's control in North Africa.

Indeed, Ptolemy had become much more popular than when he first became king. His execution sparked a huge anti-Roman revolt led by a man named Aedemon. This revolt was as difficult for the Roman military as Tacfarinas's war. It took two of the best Roman generals of that time to put it down. After the revolt ended in AD 44, Caligula's successor, Claudius, decided to take over Ptolemy's kingdom. He divided it into two new Roman provinces, Mauretania Caesariensis and Mauretania Tingitana. This brought all the land between Roman Africa and Roman Spain, and the entire Berber nation, under direct Roman rule.

See Also

- Jugurtha

- Jugurthine War

- Juba II

- Ptolemy of Mauretania

| Isaac Myers |

| D. Hamilton Jackson |

| A. Philip Randolph |