Tasmanian giant freshwater crayfish facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Astacopsis gouldi |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Dry museum specimen | |

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification |

|

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Subphylum: | Crustacea |

| Class: | Malacostraca |

| Order: | Decapoda |

| Family: | Parastacidae |

| Genus: | Astacopsis |

| Species: |

A. gouldi

|

| Binomial name | |

| Astacopsis gouldi Clark, 1936

|

|

|

|

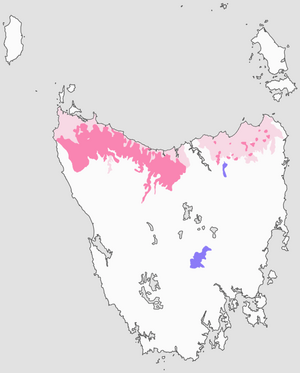

| Modelled distribution of Astacopsis gouldi Magenta: species likely to occur Light pink: species may occur Purple: translocated populations |

|

| Script error: The function "autoWithCaption" does not exist. | |

Script error: No such module "Check for conflicting parameters".

The Tasmanian giant freshwater crayfish (Astacopsis gouldi), also known as the Tasmanian giant freshwater lobster, is the largest freshwater invertebrate and crayfish on Earth. This amazing creature lives only in the rivers of northern Tasmania, an island in Australia. It is found in areas below 400 metres (1,300 ft) above sea level.

This special crayfish is listed as an endangered species on the IUCN Red List. This means it is at high risk of disappearing forever. The main reasons for this are too much overfishing and damage to its home. Because of this, it has been against the law to catch these crayfish since 1998.

The diet of the freshwater crayfish changes as it grows. They mostly eat decaying wood, leaves, and tiny living things found on them. They might also eat small fish, insects, rotting animal flesh, and other detritus if they find it. A. gouldi can live a very long time, up to 60 years! In the past, some were reported to weigh up to 6 kilograms (13 lb) and be over 80 centimetres (31 in) long. However, most large ones today are around 2–3 kilograms (4.4–6.6 lb). When fully grown, they have no natural predators because of their huge size. Smaller crayfish can be eaten by platypus, river blackfish, and rakali.

Contents

What is its Name?

Even though it is a crayfish, people in Tasmania often call this species the giant freshwater lobster. In the palawa kani language, which is spoken by Tasmanian Aboriginal people, this giant crayfish is called lutaralipina. This name is pronounced "lu-tar-rah-lee-pee-nah".

The scientific name, Astacopsis gouldi, honors Charles Gould. He was a geologist and naturalist who studied these crayfish in the 1800s. The species was first officially described in 1936 by Ellen Clark. She was a naturalist who studied Australia's crustaceans.

Biology and Life Cycle

A. gouldi are omnivorous crustaceans. This means they eat both plants and animals. Their main food is decaying wood, leaves, and the tiny living things on them. They also eat small fish, insects, and rotting animal parts when they can.

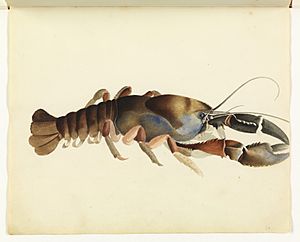

Their color can be very different from one crayfish to another. Adults can be dark brown-green, black, or even blue. For unknown reasons, crayfish in the Frankland River system are mostly blue-white. Males have larger pincers than females. Young crayfish shed their shells (moult) many times a year. This happens less often as they get older. These crayfish can live for up to 60 years. While some have been found weighing 6 kilograms (13 lb), most large ones today are 2–3 kilograms (4.4–6.6 lb).

Behaviour

We don't know much about how A. gouldi move around or migrate. But they are most active in summer and autumn when the water is warmer. They are also known to walk over land! A study in 2004 found that they often stay in one "home-pool" for 1 to 10 days. Then they might travel long distances. One crayfish moved over 700 meters in a single night.

Young crayfish might move to seasonal creeks or shallow, fast-flowing areas called riffle zones. Here, they are safer from predators like other crayfish, fish, platypus, and rakali. Larger young crayfish move to deeper, straight parts of the river. Adult crayfish have no natural predators. They hide in sheltered, deep pools. Males are territorial and may have a group of several females.

Reproduction

Tasmanian giant freshwater crayfish grow and mature very slowly. Females become ready to have babies at about 14 years old. By then, they weigh around 550 grams (19 oz) and have a carapace length of 120 millimetres (4.7 in). Males mature faster, at about 9 years old. They weigh around 300 grams (11 oz) and have a 76 millimetres (3.0 in) carapace length.

Females mate and lay eggs once every two years in autumn. This happens after they shed their shells in summer. They can lay between 224 and 1300 eggs, depending on their size. The eggs take about nine months to develop. Females carry the eggs on their tail through the winter. The babies hatch in mid-summer. They are about 6 millimetres (0.24 in) long and stay attached to their mother's swimming legs. They remain with her for a few months until autumn. This long process means females spend a lot of their lives carrying eggs and young.

Where They Live: Distribution and Habitat

Distribution

A. gouldi live in rivers and streams that are about 20–300 metres (66–984 ft) above sea level. They can be found up to 400 metres (1,300 ft) high. About 18% of the waterways where they are expected to live are in protected areas.

In the past, these crayfish lived across northern Tasmania. They were found in all rivers flowing into Bass Strait, except for the Tamar catchment. Today, their distribution is broken up. They are found only in areas that are not too disturbed. Many populations have shrunk or disappeared in several rivers. Eastern populations have especially decreased.

Habitat

A. gouldi live in slow-moving rivers and streams of different sizes. This includes headwater streams and rivulets. The water needs to be clean with lots of oxygen and little dirt floating in it. Water temperatures should be between 5.2–21 °C (41.4–69.8 °F), but they prefer cooler temperatures.

Adults need calm, deep pools with decaying logs underwater. They also need banks that hang over but are not falling apart, to hide under. Young crayfish prefer shallow, faster-flowing stream areas. They need clear hiding spots and more rocks and moss cover.

Good habitat needs healthy, native riparian vegetation. This is the plants and trees along the river banks. They should have a thick canopy that shades the water. However, these crayfish have also been found in areas with non-native plants or no plants. A study in 1994 found no crayfish in farming areas where all the riverbank plants had been removed.

Why They Are Important and What Threatens Them

Fishing for the giant freshwater crayfish was never a big business. They grow slowly and are aggressive, so they are not good for aquaculture (farming them). They are also very spiny, which makes them hard to handle after cooking. They don't have much meat compared to their total weight. However, their striking look makes them a possible attraction for tourists.

Threats and Conservation

The main reasons for the decrease in Tasmanian giant freshwater crayfish numbers are:

- Too much fishing in the past.

- Continued illegal fishing.

- Damage to their home from farming, forestry, and city activities.

Experts believe there are fewer than 100,000 left in the wild. Land clearing usually needs special approval and requires leaving 10-meter wide strips of plants along streams. Until recently, these "buffer zones" only stopped machines from working near waterways. Cutting trees and burning were allowed right up to the stream edge.

A. gouldi is protected by Australian laws. These laws make it illegal to catch or handle the crayfish without a special permit. There is a large fine of A$10,000 for breaking this law. Even though fishing in the past caused big problems, some illegal fishing still happens. This can greatly threaten the remaining populations. New roads can also allow illegal fishers to reach areas where crayfish were once safe.

Habitat Disturbance

Damage to their habitat includes:

- Removing or destroying native riparian plants along riverbanks.

- Riverbanks eroding (washing away).

- Removing snags (fallen logs and branches in the water).

- Changes to stream flow, like culverts (pipes under roads) and farm dams.

- Siltation (too much mud and dirt in the water).

- Toxic chemicals running off into the water.

When plants are removed from riverbanks, the banks become unstable. This harms the crayfish's burrowing homes and adds more dirt to the water. More dirt in the water makes it harder for the crayfish to breathe through its gills. Losing the tree cover over the water also lets more sunlight in, which makes the water warmer. This is bad for the crayfish.

Some rivers in Tasmania are heavily affected by hydro-electric schemes. These use barriers in the river that can stop crayfish from moving around. Taking water for farming and cities is also a concern.

Notable Events

In 1994, a large chemical spill from a plant caused many crayfish to die in the Hogarth Rivulet and Great Forester River. Locals and fisheries officers reported that there was little life left in much of the river. This event severely harmed any crayfish populations there.

The 2016 Tasmanian floods also caused worries for the crayfish. Up to 100 dead crayfish were found along the banks of the Leven River. This was likely caused by the strong water flows during the flood. There are also concerns that the floods washed away snags from the waterways. These snags are a very important part of the crayfish's habitat.

Important Locations for Conservation

The 2006–2010 Giant Freshwater Lobster Recovery Plan pointed out several river areas. These areas were found to have good habitat and healthy crayfish populations. They should be considered for conservation efforts. Some areas need to be checked again, as their habitat quality might have changed.

- Aitken Creek (downstream of Nook Road to Sheffield Road crossing)

- Black River and its smaller streams (tributaries)

- Dip Range streams

- Duck River catchment (above Trowutta Road)

- Emu River tributaries

- Flowerdale River (from the top of the catchment to near Lapoinya)

- Great Forester River and tributaries

- Inglis River and tributaries

- Little Forester River and tributaries

- Cam River catchment

- Hebe River (part of the Flowerdale River catchment)

- Arthur River catchments, including Frankland, Rapid, Keith, and Lyons rivers

| Jackie Robinson |

| Jack Johnson |

| Althea Gibson |

| Arthur Ashe |

| Muhammad Ali |