Māori language

Quick facts for kids Māori |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Māori, te reo Māori | ||||

| Native to | New Zealand | |||

| Region | Polynesia | |||

| Ethnicity | Māori | |||

| Native speakers | 50,000 (well or very well) (2015) 186,000 (some knowledge) (2018) |

|||

| Language family | ||||

| Writing system | Latin (Māori alphabet) Māori Braille |

|||

| Official status | ||||

| Official language in | New Zealand | |||

| Regulated by | Māori Language Commission | |||

| Linguasphere | 39-CAQ-a | |||

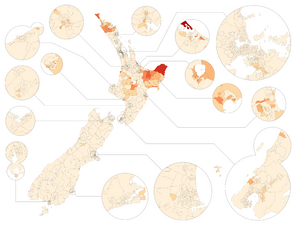

Māori language distribution within New Zealand

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

Māori, also known as te reo Māori (which means 'the Māori language'), is the language of the Māori people. They are the original people of mainland New Zealand. You might also hear it called just te reo.

Māori is part of the Eastern Polynesian language group. This means it's related to languages like Cook Islands Māori, Tuamotuan, and Tahitian. It's also part of the larger Austronesian language family.

Before Europeans arrived, Māori people didn't have a written language. They used spoken words to share stories and history. Today, written Māori uses the Latin script. This was set up in the 1800s with help from English clergy.

For a while, the Māori language faced challenges. After 1945, fewer people spoke it. But in the late 20th century, a movement started to bring the language back. This was part of the Māori protest movement and the Māori renaissance in the 1970s. Thanks to places like kōhanga reo (Māori-language kindergartens), more children are learning Māori as their first language.

In 2018, about 190,000 people in New Zealand could have an everyday conversation in Māori. This is about 4% of the population. Many more people have some knowledge of the language. Māori people see their language as one of their most important cultural treasures, called taonga.

Contents

- What is the Māori Language Called?

- Is Māori an Official Language?

- How Did the Māori Language Begin?

- Why Did Māori Decline?

- How is Māori Being Revived?

- Where is Māori Spoken?

- How is Māori Written?

- How Does Māori Grammar Work?

- How Has Māori Influenced English?

- Online Tools for Māori

- Images for kids

- See also

What is the Māori Language Called?

The English word Maori comes from the Māori language. In Māori, it's spelled Māori. In New Zealand, people often call the language te reo, which means "the language." This is a shorter way of saying te reo Māori, or "the Māori language."

Is Māori an Official Language?

Yes, Māori is one of New Zealand's official languages. The other is New Zealand Sign Language. New Zealand English is also widely used, but it's not officially declared. Te reo Māori became an official language in 1987 with the Māori Language Act.

Many government groups now have names in both English and Māori. You might see bilingual signs in public places like libraries. You can even talk to government agencies in Māori. If you do, an interpreter will usually be there to help.

Members of the New Zealand Parliament can speak in Māori during meetings. Interpreters are available for this. You can also speak Māori in court, but you need to tell the court beforehand.

In 1994, a court ruling said the government must help protect the Māori language. Because of this, Māori Television started in 2004. It broadcasts some shows in Māori. In 2008, a second channel called Te Reo launched. It broadcasts only in Māori, with no ads or subtitles.

Also, in 2008, official place names started to include macrons. Macrons are special marks over vowels that show they are long sounds.

How Did the Māori Language Begin?

Māori legends say their ancestors came to New Zealand from a place called Hawaiki. Experts believe they came from eastern Polynesia, possibly from the Cook Islands or Society Islands. They traveled by large canoes, arriving around the year 1350.

Once in New Zealand, the Māori language developed on its own. Over time, six different ways of speaking (dialects) appeared. This happened because different Māori tribes (called iwi) lived in separate areas.

Before Europeans arrived, Māori did not have a writing system. However, some historians think that tā moko, the traditional Māori art of tattooing, was a way of communicating. It was like a visual language.

The Māori language is known for its beautiful and meaningful poetry and stories. These include:

- karakia: special chants or prayers used for spiritual guidance.

- whaikōrero: traditional speeches given on a marae (a Māori meeting ground).

- whakapapa: stories of a person's ancestors and family history.

- karanga: a special call or welcome, often used by women.

- haka: a powerful dance or challenge.

- mōteatea and waiata: traditional songs.

Historian Atholl Anderson said that whakapapa used rhymes and repeated patterns. This helped people remember the information easily.

Why Did Māori Decline?

In the 1800s, Māori was the main language in New Zealand. European traders and missionaries even learned it. But as more European settlers arrived, English became more common.

In the late 1800s, schools started teaching mostly in English. The Native Schools Act meant that Māori was slowly removed from school lessons. More Māori people began to learn English.

Before World War II (1939–1945), most Māori people still spoke Māori as their first language. They used it at home, in church, and in political meetings. Some Māori newspapers and books were also published.

After World War II, many Māori families moved to cities. In some schools, children were not allowed to speak Māori. Some older Māori people remember being punished for speaking their language at school.

By the 1980s, less than 20% of Māori people spoke the language well. Many Māori children were not learning their ancestral language. This led to generations of Māori people who didn't speak Māori.

How is Māori Being Revived?

Since about 2015, the Māori language has become popular again. Many New Zealanders, even those without Māori roots, see it as an important part of their country's culture. Surveys show that Māori is now highly respected by Māori people and accepted by most non-Māori New Zealanders.

More people want to learn Māori. Businesses like Google and Vodafone NZ have started using te reo. This shows customers that they care about New Zealand's culture. You can hear Māori more often in the news and in politics.

Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern even used a Māori proverb when toasting leaders in 2018. Disney has also started dubbing its animated movies into Māori, starting with Moana in 2017.

In 2017, Rotorua became the first city in New Zealand to be officially bilingual. This means both Māori and English are promoted there. In 2019, the New Zealand government launched a plan called Maihi Karauna. Its goal is to have 1 million people speaking te reo Māori by 2040. Also, the Harry Potter books are being translated into Māori!

While most people support the revival, some New Zealanders have disagreed with it. They have complained about Māori place names or Māori language being used on police cars or by broadcasters. However, in 2021, the Broadcasting Standards Authority said that using Māori language on TV or radio does not break any rules.

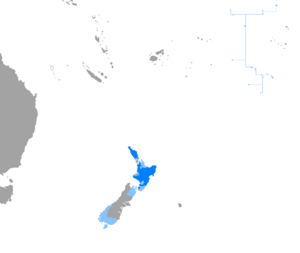

Where is Māori Spoken?

Most Māori speakers live in New Zealand. In 2013, about 21.3% of Māori people said they could have a conversation in the language. Only a small number of these people (about 1.4% of all Māori) spoke only Māori.

Māori is still a community language in some areas, like Northland, Urewera, and East Cape. Kohanga reo (Māori-immersion kindergartens) use only Māori. More and more Māori parents are raising their children to speak both Māori and English.

When Māori families moved to cities after World War II, English became their main language. So, most Māori speakers today also speak New Zealand English.

A small number of Māori speakers live outside New Zealand. For example, in Australia, about 11,747 Māori people spoke Māori at home in 2016.

How is Māori Written?

The modern Māori alphabet has 15 letters. These include five vowels and ten consonants. The vowels can be short or long. Long vowels are shown with a macron (a line) above them, like ā, ē, ī, ō, ū.

| Consonants | Vowels | |

|---|---|---|

| Short | Long | |

The letters are ordered like this: A, E, H, I, K, M, N, O, P, R, T, U, W, Ng, Wh.

History of Writing Māori

Māori did not have its own writing system. Some people thought that rock carvings or kōwhaiwhai (rafter paintings) might have been a form of writing. But there's no proof they were a full writing system.

When Europeans like Captain James Cook first tried to write Māori words, it was hard. They often missed sounds or spelled words differently.

In 1814, missionaries began to try and write down the sounds of the language. Thomas Kendall published a Māori book in 1815. Later, in 1820, a standard way of writing Māori was created. This was done by Samuel Lee from Cambridge University, working with Māori chiefs Hongi Hika and Waikato.

The Māori people were very eager to learn to read and write. Missionaries said that Māori taught each other using whatever they could find, like leaves and charcoal.

Long Vowels

The first writing system for Māori didn't show long vowels. But vowel length is very important in Māori! It can change the meaning of a word.

| ata | morning | āta | carefully |

| keke | cake | kēkē | armpit |

| mana | prestige | māna | for him/her |

| manu | bird | mānu | to float |

| tatari | to wait for | tātari | to filter or analyse |

| tui | to sew | tūī | parson bird |

| wahine | woman | wāhine | women |

Over time, Māori speakers started to mark long vowels in their own writings. They used marks like macrons or doubled letters. Today, macrons (tohutō) are the standard way to show long vowels. The Māori Language Commission decided this. Most news websites and newspapers now use macrons.

Sometimes, people still use double vowels instead of macrons. For example, the Waikato-Tainui tribe prefers them.

How Does Māori Grammar Work?

Māori sentences usually follow a "verb-subject-object" order. This means the action word comes first. For example, "cooked I the fish."

Māori doesn't change words much for things like tense (past, present, future). Instead, it uses small words called "particles" to show these meanings.

Māori also has special ways to talk about "possession." For example, there are different ways to say "my" depending on if you control the thing you own.

How Has Māori Influenced English?

New Zealand English has borrowed many words from Māori. These are often names of birds, plants, fish, and places. For example, the kiwi bird gets its name from te reo.

"Kia ora" is a common Māori greeting. It means "be healthy," but people use it to say "hello" or "thank you." Other common Māori greetings are tēnā koe (to one person) and tēnā koutou (to three or more people).

The phrase kia kaha means "be strong." People often say it to encourage someone. Many other words like whānau (family) and kai (food) are also used by New Zealanders.

In 2023, the Oxford English Dictionary added 47 new words or phrases from New Zealand English. Most of these came from te reo Māori.

Online Tools for Māori

You can find Māori on online translators like Google Translate and Microsoft Translator. A popular online dictionary for Māori is Te Aka Māori Dictionary.

Images for kids

-

Bastion Point land rights activists with Māori-language signs

-

Bilingual sign in Broadwood, Northland

See also

In Spanish: Idioma maorí para niños

In Spanish: Idioma maorí para niños