Te Wahipounamu facts for kids

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Location | South Island, New Zealand |

| Criteria | Natural: vii, viii, ix, x |

| Inscription | 1990 (14th Session) |

| Area | 2,600,000 ha |

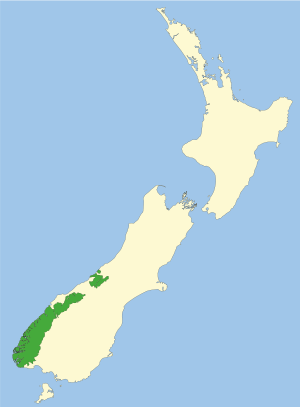

Te Wāhipounamu means "the place of greenstone" in the Māori language. It is a special World Heritage Site located in the southwest part of New Zealand's South Island.

This amazing area was added to the World Heritage List in 1990. It covers a huge 26,000 square kilometers (about 10,000 square miles)! Te Wāhipounamu includes four important national parks:

Scientists believe this area shows us what the ancient supercontinent Gondwana might have looked like. This is one big reason why it's a World Heritage Site.

Contents

Discover Te Wāhipounamu: New Zealand's Natural Treasure

Te Wāhipounamu stretches for 280 miles along the western coast of New Zealand's South Island. The land here goes from sea level all the way up to 12,349 feet at Aoraki/Mt. Cook. In some spots, it reaches inland as far as 56 miles.

This region is full of incredible natural sights. You can find snow-capped mountains, bright blue lakes, stunning waterfalls, deep fjords, and wide valleys. It's also home to many active glaciers. The two most famous are Franz Josef Glacier and Fox Glacier. Te Wāhipounamu is New Zealand's largest natural area that has been changed the least by humans. Because of this, its plants and animals are the best modern examples of life from ancient Gondwanaland.

Plants of Te Wāhipounamu: A Green Wonderland

The plants in Te Wāhipounamu are very diverse and almost untouched. On the mountains, you'll see rich alpine plants. These include shrubs, tussock grasses, and many different herbs.

In the warmer, lower rainforests, tall podocarp trees are common. The western parts have even more rainforests and wetlands. This area also has New Zealand's largest and most natural freshwater wetlands. The Westland coastal plain is known for its fertile swamps and peat bogs.

Animals of Te Wāhipounamu: Unique Wildlife

Te Wāhipounamu is home to many native animals. It has the largest group of forest birds in New Zealand. The rare takahe bird lives in a few mountain valleys in Fiordland. There are only about 170 of these birds left in the wild.

Along the southwest coast, you can find most of New Zealand's Fur Seals. Other animals living here include the Southern Brown Kiwi, Great Spotted Kiwi, Yellow-crowned parakeet, Fiordland Penguin, New Zealand Falcon, and Brown teal. The kakapo, the world's rarest and heaviest parrot, used to live here. But it is now thought to be gone from the mainland.

People and Life in Te Wāhipounamu

Te Wāhipounamu is the least populated part of New Zealand. Most people who live here work in tourism. But there are other jobs too. Along the coast, people work in fishing, farming, and small-scale mining.

In the eastern part of the World Heritage area, farming is the main activity. Sheep and cattle grazing is allowed with special permission. However, being a World Heritage Site has limited how much land can be used for these activities.

Land Shapes: Mountains and Glaciers

Te Wāhipounamu is one of the most active earthquake regions in the world. It sits where two huge land plates meet: the Pacific plate and the Indo-Australian plate. The mountains in this area were formed by these plates moving over the last five million years.

Glaciers are also a big part of the landscape. Their basic shape was set during the ice ages. But there have been many changes since then. These changes are bigger in the Southern Alps than in the Fiordlands. You can see deep gullies, jagged ridges, and rockfalls. Landslides can happen, but they are not common. Even with few people and roads, landslides could affect tourist areas in the Southern Alps.

Māori Connections to the Land

The entire Te Wāhipounamu region is very important to the Ngāi Tahu tribe of the Māori people. Their family lands cover almost all of the South Island.

Legends of the Land's Creation

The Māori have a special legend about how this region and the South Island were formed. It says that four sons of Rakinui, the Sky Father, came down from the heavens. They sailed around Papatuanuku, the Earth Mother. Their canoe hit a reef, and the brothers got stuck. A cold wind from the Tasman Sea turned them into stone. Their canoe became the South Island of New Zealand. The tallest brother, Aoraki, is now Aoraki Mt. Cook. His brothers and the rest of the crew became the other mountains of the Southern Alps.

The Māori also have a legend for the Franz Josef Glacier and Fox Glacier. It starts with Hinehukatere, who loved climbing mountains. One day, she convinced her lover, Tawe, to join her. An avalanche killed Tawe, and he came to rest in Fox Glacier. The Māori name for Fox Glacier is Te Moeke o Tauwe, which means "the bed of Tauwe." After Tawe's death, Hinehukatere was so sad that she cried many tears. These tears froze to form Franz Josef Glacier. The Māori name for Franz Josef Glacier is Ka Roimata o Hinehukatere, meaning "the tears of Hinehukatere."

Using the Land: Greenstone

This area was, and still is, a key place to find pounamu greenstone, also known as jade. This precious stone is used by the Māori to make tools, weapons, and beautiful jewelry.

Te Wāhipounamu: A UNESCO World Heritage Site

Te Wāhipounamu was added to the UNESCO World Heritage List in 1990. Before this, the Westland and Mount Cook National Park and the Fiordland National Park were already on the list. Now, they are all part of the larger Te Wāhipounamu site.

To be on this list, Te Wāhipounamu met several important rules:

- It has many natural features that make New Zealand famous for its amazing landscapes.

- It is seen as the best modern example of life from ancient Gondwanaland. This makes it important worldwide.

- It has a huge variety of geology and living things. Its natural homes are mostly untouched.

- It shows a wide range of New Zealand's unique plants and animals. These show how life here has changed over time, isolated from other places.

Protecting Te Wāhipounamu

Most of the land in Te Wāhipounamu is owned by the New Zealand government and people. It is managed by the Department of Conservation.

Working with the Ngāi Tahu Tribe

The Treaty of Waitangi gives the Ngāi Tahu people special importance and rights over the land. The Department of Conservation must follow the rules of this treaty. This means they work together with the Ngāi Tahu people. They have a yearly plan where the Ngāi Tahu tribe can help manage the area.

The treaty was not always followed perfectly in the past. But a special agreement was made around the time Te Wāhipounamu became a World Heritage Area. This agreement had three main parts:

- Mount Cook became known as Aoraki / Mount Cook. Also, 88 other places were given both Māori and English names.

- The ownership of Aoraki was given back to the Ngāi Tahu Tribe. They then gave it as a gift to all the people of New Zealand.

- The Tribe was given rights to enter and temporarily stay in the area. This was for gathering traditional foods and materials.

Visiting Te Wāhipounamu: Tourism and Adventure

The main places tourists love to visit in Te Wāhipounamu are Milford Sound and the Milford Track. Other popular spots include Lake Te Anau and the Kepler Track, the Routeburn Track and Mount Aspiring. Also, Aoraki / Mount Cook and the Tasman Glacier, and the Franz Josef Glacier and Fox Glacier.

There are only two main roads in the region: the Haast Highway and Milford Highway. These are called "Heritage Highway" corridors. Along them, you'll find ten visitor centers and many nature walks. People come to Te Wāhipounamu, and New Zealand in general, for its amazing natural beauty. Visitors are often motivated by the scenery and fun outdoor activities.

Tourism here is mostly about nature. It's a mix of nature-based and adventure activities. You can enjoy quiet walks in the National Parks, go whale-watching, or take boat tours in the Fiordland Sounds. There are also more adventurous activities like tramping (trekking). This might involve crossing rivers or mountain passes while enjoying the views. Even activities like glacier walks, rafting, and climbing happen in the natural environment.

Wilderness Areas: Untouched Nature

Within Te Wāhipounamu, there are four special wilderness areas. These are Hooker-Landsborough (41,000 ha), Olivine (80,000 ha), Pembroke (18,000 ha), and Glaisnock (125,000 ha). Together, these wilderness areas make up 10% of Te Wāhipounamu.

They are managed very strictly under the New Zealand Wilderness Policy. This policy says that wilderness areas are "wildlands that appear to have been affected only by the forces of nature." Any signs of human activity should be almost invisible. These areas are kept natural. There are no visitor facilities like roads, huts, bridges, or even tracks. You also cannot fly into these areas for fun or business. Visitors enter these areas "on nature's terms."

These wilderness areas help keep alive the idea of pure, untouched nature. Famous people like John Muir and Aldo Leopold supported protecting wilderness. Their ideas helped start the environmental movement in the United States. New Zealand's policy is similar. It aims to protect land for enjoyment while keeping it almost untouched by humans.

Challenges for Te Wāhipounamu

There are still some issues in Te Wāhipounamu that need to be solved:

- Road Proposal: There's an environmental concern about a proposed Haast-Hollyford Road. This idea has been around since the 1870s.

- Māori Partnership: There's a need to build a stronger working partnership with the Ngāi Tahu iwi Tribe. While there's a plan, making it a true partnership is an ongoing challenge.

- Aircraft Noise: More tourist planes mean more noise. This noise disturbs the "natural quiet" of the region, which many people want to protect.

- Coastal Protection: The World Heritage Area does not currently include the ocean parts. Many feel there's a need to better protect the coastal wilderness.

- Invasive Species: One of the biggest problems is invasive species. These are plants or animals that are not native to the area and cause harm. Increases in red deer and other animals like wapiti, goats, and fallow deer have caused a lot of damage. They especially threaten the forests and mountain ecosystems. Commercial hunting helps reduce these numbers. The Department of Conservation also has programs to control them. Their goal is to get rid of new invasive species and reduce or remove existing ones.

See also

In Spanish: Te Wahipounamu para niños

In Spanish: Te Wahipounamu para niños

| Stephanie Wilson |

| Charles Bolden |

| Ronald McNair |

| Frederick D. Gregory |