USS Olympia (C-6) facts for kids

USS Olympia (C-6), port bow, 10 February 1902

|

|

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | Olympia |

| Namesake | The City of Olympia, Washington |

| Ordered | 7 September 1888 |

| Builder | Union Iron Works, San Francisco, California |

| Laid down | 17 June 1891 |

| Launched | 5 November 1892 |

| Sponsored by | Miss Ann B. Dickie |

| Commissioned | 5 February 1895 |

| Decommissioned | 9 November 1899 |

| Recommissioned | January 1902 |

| Decommissioned | 2 April 1906 |

| Recommissioned | 1916 |

| Decommissioned | 9 December 1922 |

| Reclassified |

|

| Refit | 1901, 1902, 1916 |

| Stricken | 11 September 1957 |

| Identification |

|

| Nickname(s) | "Queen of the Pacific", "The Winged O" |

| Fate | Restored as museum ship |

| Status | Museum ship. |

| General characteristics (as built) | |

| Type | Protected cruiser |

| Displacement | |

| Length | 344 ft 1 in (104.88 m) |

| Beam | 53 ft (16 m) |

| Draft | 21 ft 6 in (6.55 m) |

| Installed power | 17,000 ihp (13,000 kW) |

| Propulsion |

|

| Speed | 21.7 knots (40.2 km/h; 25.0 mph) |

| Range | 6,000 nmi (11,000 km; 6,900 mi) at 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph) |

| Capacity | 1,169 short tons (1,060 t) coal (maximum) |

| Complement | 33 officers and 395 enlisted |

| Armament |

|

| Armor |

|

| General characteristics (1917) | |

| Armament | 10 × 5 in (127 mm)/51 cal Mark 8 guns (10×1) |

|

Olympia

|

|

USS Olympia (C-6) at the Independence Seaport Museum in 2007.

|

|

| Location | Penn's Landing Marina, South Columbus Blvd. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States |

| Area | Less than one acre |

| Built | 1892 |

| Built by | Union Iron Works of San Francisco |

| NRHP reference No. | 66000692 |

| Added to NRHP | 15 October 1966 |

The USS Olympia (C-6) is a famous protected cruiser that served in the United States Navy. She was active from 1895 until 1922. Today, she is a special museum ship in Philadelphia, where visitors can explore her history.

Olympia became very well-known as the main ship, or flagship, for Commodore George Dewey. This was during the exciting Battle of Manila Bay in the Spanish–American War in 1898. After returning to the U.S. in 1899, the ship was taken out of service.

However, Olympia was brought back into action in 1902. Before World War I, she was used to train young naval cadets. She also served as a floating home for sailors in Charleston, South Carolina. In 1917, she was called back for war duty. She helped patrol the American coast and protected transport ships.

After World War I, Olympia played a role in the Allied intervention during the Russian Civil War in 1919. She also sailed through the Mediterranean and Adriatic Seas. Her mission was to help keep peace in the Balkan countries, which were facing a lot of changes.

In 1921, Olympia carried the remains of the Unknown Soldier from France. This brave soldier from World War I was brought to Washington, D.C.. His body was laid to rest in Arlington National Cemetery. Olympia was taken out of service for the last time in December 1922.

In 1957, the U.S. Navy gave the ship to the Cruiser Olympia Association. They worked hard to restore her to how she looked in 1898. Since then, Olympia has been a museum ship in Philadelphia. She is now part of the Independence Seaport Museum. In 1966, Olympia was named a National Historic Landmark.

Olympia is the oldest steel American warship that is still floating today. Keeping her in good shape requires a lot of work and money. The museum has been working hard to get funding and make important repairs to the ship.

Contents

In the late 1800s, the United States Navy was getting a big upgrade. Leaders wanted stronger, faster ships. This was to protect American interests and trade around the world.

In 1888, the government decided to build a new type of large, fast ship. This ship would be able to attack enemy supply lines. Olympia was one of these new "protected cruisers."

A new plan for the navy came along, focusing on powerful battle fleets. This meant Olympia became a unique ship. She was the only one of her kind ever built.

Designing and Building Olympia

The design for Cruiser Number 6, which became Olympia, started in 1889. Engineers debated how many and what kind of guns to put on the ship. They also discussed how to best protect it with armor.

The Union Iron Works in San Francisco, California, won the contract to build the ship. The contract was signed in July 1890. The ship's keel (the bottom part of the ship's frame) was laid on June 17, 1891. Olympia was officially launched on November 5, 1892.

Building the ship took longer than expected. This was because some parts, like the new Harvey steel armor, were delayed. The last small gun was not delivered until December 1894.

Speed Trials and Commissioning

Olympia had her first tests in November 1893. She reached a speed of 21.26 kn (39.37 km/h). This was very fast for the time. After some minor fixes, she had an official speed trial in December.

During this trial, Olympia reached an average speed of 21.67 kn (40.13 km/h). This was much faster than the required 20 kn (37 km/h). She was officially put into service, or commissioned, on February 5, 1895. For a while, she was the biggest ship built on the U.S. West Coast.

Ship Features

Olympia is 344 ft 1 in (104.88 m) long. She is 53 ft (16 m) wide and sits 21 ft 6 in (6.55 m) deep in the water. She was powered by two large steam engines. These engines gave her a top speed of over 21 kn (39 km/h).

The ship had a crew of about 411 to 447 officers and sailors.

Weapons

Olympia had many weapons. Her main guns were four 8 in (203 mm) guns. These were in two rotating gun turrets, one at the front and one at the back. These powerful guns could fire heavy shells.

She also had ten 5 in (127 mm) guns along her sides. These were placed in special armored rooms called casemates. For smaller threats, she had fourteen 6-pounder guns and six 1-pounder guns. She also carried Gatling guns and six torpedo tubes. Over time, many of these guns were updated or replaced.

Protection

Olympia was protected by strong steel armor. Her command center, called the conning tower, had 5 in (13 cm) thick steel. The ship's deck had armor that was 2 in (5.1 cm) thick in some places and up to 4.75 in (12.1 cm) thick on the sides.

The main gun turrets had 3.5 in (8.9 cm) of armor. The bases of these turrets, called barbettes, had 4.5 in (11 cm) thick armor. The 5-inch guns also had protective gun shields.

Olympia in Service

After being commissioned in February 1895, Olympia sailed to the Mare Island Naval Shipyard. There, she was fully prepared for duty. In April, she took part in a festival in Santa Barbara. Sadly, during a gunnery practice, a sailor was killed in an accident.

In August, Olympia left the U.S. for China. She became the main ship for the Asiatic Squadron. For the next two years, she trained with other ships and visited many Asian ports. In January 1898, Commodore George Dewey took command of the squadron from Olympia.

The Spanish–American War

As war with Spain seemed likely, Olympia got ready in Hong Kong. When war was declared on April 25, 1898, Dewey moved his ships to Mirs Bay, China. Two days later, the Navy ordered the squadron to Manila in the Philippines. A Spanish naval force was protecting Manila's harbor. Dewey's mission was to defeat them.

Battle of Manila Bay

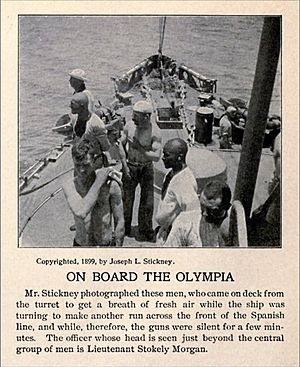

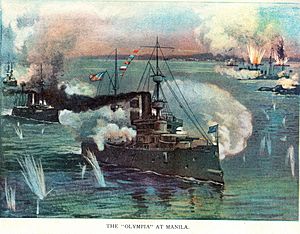

On May 1, Commodore Dewey led his ships into Manila Bay. His flag was flying on Olympia. They faced the Spanish fleet. The Spanish ships were near the shore, protected by old coastal guns. At about 5:40 a.m., Dewey gave his famous order to Olympia's captain, "You may fire when you are ready, Gridley".

The first shot of the battle came from Olympia's front eight-inch gun. The American ships then began firing. The Spanish guns were not very accurate. The battle quickly became one-sided. Dewey paused the fight briefly to let his crews eat breakfast.

By early afternoon, Dewey had destroyed the Spanish fleet and shore batteries. His own ships were mostly unharmed. Dewey then anchored his ships and accepted the surrender of Manila.

News of Dewey's victory quickly reached the U.S. Both he and Olympia became national heroes. Olympia stayed in the Philippines to help the Army. She returned to the U.S. in October 1899, sailing through the Suez Canal. In Boston, her crew was celebrated. On November 9, Olympia was taken out of service.

Before World War I

Olympia was brought back into service in January 1902. She joined the North Atlantic Squadron. She served as the flagship for the Caribbean Division. For the next four years, she patrolled the Atlantic and Mediterranean Seas. She even visited the Ottoman Empire.

From 1906, she became a training ship for young sailors from the United States Naval Academy. She made three summer training cruises. Between these trips, she was kept in reserve. In 1912, Olympia became a barracks ship in Charleston, South Carolina. She stayed there until 1916. In late 1916, she was recommissioned as the U.S. prepared for World War I.

World War I Service

When the U.S. entered World War I in April 1917, Olympia became the flagship of the U.S. Patrol Force. She patrolled the eastern U.S. coast for German warships. She also protected transport ships in the North Atlantic.

In June 1917, she ran aground and needed repairs. Her old eight-inch guns were replaced with newer five-inch guns. In April 1918, Olympia carried soldiers to Russia. Russia was in the middle of a civil war. Olympia helped with peacekeeping efforts in Murmansk and Archangel.

After the war, Olympia sailed to the Mediterranean. In December 1918, she became the flagship for American naval forces there. She continued to visit ports and promote peace. She helped keep order in the Adriatic Sea after the Austro-Hungarian Empire collapsed.

In 1920, she was reclassified as CA-15. She then helped sink former German warships in experiments. Later that year, she was reclassified again as CL-15.

Bringing Home the Unknown Soldier

On October 3, 1921, Olympia left Philadelphia for Le Havre, France. Her mission was to bring the remains of the Unknown Soldier home. This soldier would be buried in Arlington National Cemetery.

On October 25, a special ceremony took place. The casket with the Unknown Soldier was brought aboard Olympia. The ship received a 17-gun salute as she departed. She was escorted by other ships. During the journey, Olympia faced two tropical storms.

On November 9, Olympia arrived at the Washington Navy Yard. After the remains were taken ashore, the cruiser fired her guns in salute. She then completed one last training cruise for midshipmen in the summer of 1922.

Olympia as a Museum Ship

On December 9, 1922, Olympia was taken out of service for the last time in Philadelphia. She was kept in reserve. In 1931, she was reclassified as IX-40, meant to be preserved as a historic ship.

In 1957, the Cruiser Olympia Association took over her care. They restored her to how she looked in 1898. Her main eight-inch guns, which had been removed, were replaced with replicas. In 1996, the association joined with the Independence Seaport Museum (ISM) in Philadelphia.

Today, Olympia is a museum ship at Penn's Landing in Philadelphia. She is the only floating ship left from the U.S. Navy's fleet in the Spanish–American War. Students from Naval Reserve Officer Training Corps programs help maintain her. Parts of Olympia, like her stern plate and bow ornaments, are on display at the United States Naval Academy.

Historic steel ships need to be taken out of the water for maintenance every 20 years. However, Olympia has been in the water since 1945. This means she needs a lot of repairs. The museum has worked hard to raise money and find solutions to keep her afloat.

In 2014, the ISM decided that Olympia would stay in Philadelphia. They launched a big fundraising campaign to pay for her long-term preservation.

Recent Preservation Projects

The ISM is dedicated to restoring Olympia. They have received grants from various organizations and private donors. Over the years, the museum has spent over $10 million to maintain the ship. This included removing harmful materials and making safety upgrades.

In 2015, Olympia received grants to repair her hull plates and deck leaks. Workers used a special device to clean and treat sections of the hull underwater. In 2017, the museum replaced gangways, restored parts of the ship, and built replicas of historic furniture.

The museum has started a national campaign to raise $20 million. This money is needed to put Olympia in a drydock. This will allow for full repairs to her hull below the waterline. These efforts aim to make the ship more accessible and teach people about her important history. In May 2017, the museum opened a new exhibit about Olympia and World War I.

Awards and Honors

| Dewey Medal | Navy Expeditionary Medal | Spanish Campaign Medal |

| Philippine Campaign Medal | Dominican Campaign Medal | World War I Victory Medal with "WHITE SEA" clasp |

See also

In Spanish: USS Olympia (C-6) para niños

In Spanish: USS Olympia (C-6) para niños