Xinjiang under Qing rule facts for kids

| Xinjiang under Qing rule | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Quick facts for kids Military governorate later province of the Qing dynasty |

|||||||||

| 1759–1912 | |||||||||

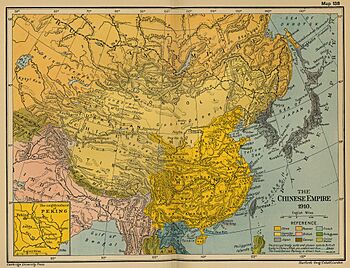

Xinjiang within the Qing dynasty in 1820. |

|||||||||

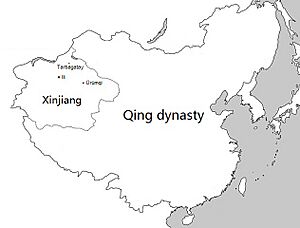

Location of Xinjiang under Qing rule |

|||||||||

| Capital | Ili (c. 1762–1871) Ürümqi (1884–1912) |

||||||||

| • Type | Qing hierarchy | ||||||||

| History | |||||||||

|

• Established

|

1759 | ||||||||

| 1862–1877 | |||||||||

|

• Conversion into province

|

1884 | ||||||||

|

• Disestablished

|

1912 | ||||||||

|

|||||||||

The Manchu-led Qing dynasty of China ruled over Xinjiang for a long time. This period lasted from the late 1750s until 1912. In the history of Xinjiang, Qing rule began after the Dzungar Khanate was defeated. This happened during the final part of the Dzungar–Qing Wars. Qing rule continued until the dynasty fell in 1912.

To manage Xinjiang, the Qing government created the job of General of Ili. This general reported to the Lifan Yuan. The Lifan Yuan was a special Qing agency. It was in charge of the empire's border areas. In 1884, Xinjiang officially became a province of China.

Contents

Understanding Xinjiang's History

What does "Xinjiang" mean?

The name "Xinjiang" (Chinese: 新疆; pinyin: Xīnjiāng; literally "new frontier") was first used during the time of the Qianlong Emperor (1735–1796). It was initially called "Xiyu Xinjiang," meaning "new frontier of the Western Regions." By the late 1700s, "Xinjiang" became the common name. This happened under the General of Ili Songyun.

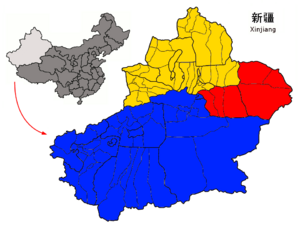

The region was divided into three main parts:

- Zhunbu (or Dzungaria) in the north, also known as Tianshan Beilu (Northern March).

- Huibu (Muslim Region) in the south, also called Tianshan Nanlu (Southern March) or Huijiang (Muslim frontier).

- Tianshan Donglu (Eastern March) in the east. This area was known for its many merchants.

Outside of China, southern Xinjiang had many different names. These included the Tarim Basin, Chinese Turkestan, and East Turkestan. The local Uyghur people called southern Xinjiang Altishahr, which means "six cities."

Who are the Uyghurs?

During the Qing period, there wasn't one single name for the people we now call the Uyghurs. Before the Qing, "Uyghur" referred to non-Muslims in Qocho, mostly Buddhists. This term was not used for the modern Uyghur people until 1921.

Before then, people from the oasis cities in Xinjiang were often called Sart by outsiders. This word originally meant "merchant." It was used by Turkic and Mongolic groups for Iranian people they ruled. Later, it meant someone who lived a settled life. Foreigners also called them Tartars.

The Chinese called these oasis people chantou, meaning "turban head." However, this term was also used for the modern Hui people (Dungan people) in Xinjiang. The Qing government used Huihu (Uyghur) in 1779 for some rebel leaders. But they didn't connect Huihu only to oasis people. They used Hui for both Chinese-speaking Muslims and Xinjiang Muslims in general.

In northern Xinjiang, these people were known as Taranchi. This is a Mongolian word for "farmer." They were moved there by the Dzungar Khanate as workers. Locals often identified themselves by their city, like Kashgaris or Khotanese. They used musulman to tell themselves apart from non-Muslims and Dungans.

Who are the Dungans?

Chinese-speaking Muslims in the northwest were called the Dungans. Their name was written in different ways, like Tungan or Donggan. Qing documents also called them hanhui. The oasis people of Xinjiang used musulman to show they were different from the Dungans.

How Qing Rule Began

The Dzungar-Qing Wars

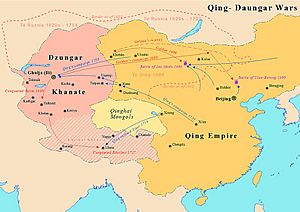

Before the Qing, Xinjiang was ruled by the Oirat Mongols of the Dzungar Khanate. Their main area was Dzungaria in northern Xinjiang. The Dzungars lived in a large area, from the Great Wall of China to eastern Kazakhstan. They were the last nomadic empire to challenge China. They fought wars against the Qing dynasty in the mid-1700s.

In 1680, the Dzungars took over the Tarim Basin. This area was then ruled by the Yarkent Khanate. In 1690, the Dzungars attacked the Qing. They were forced to retreat. In 1696, the Qing defeated the Dzungar ruler Galdan Khan. From 1693 to 1696, the Tarim Basin rulers rebelled against the Dzungars. This led to Abdullah Tarkhan Beg of Hami joining the Qing.

In 1717, the Dzungars invaded Tibet. Tibet was an ally of the Qing. The Qing fought back but were defeated in 1718. A larger Qing army was sent in 1720. They successfully drove the Dzungars out of Tibet. People in Turpan and Pichan rebelled under Emin Khoja and joined the Qing.

The Dzungars then attacked the Khalka Mongols, who were under Qing rule. This led to another Qing defeat. In 1730, the Dzungars attacked Turpan again. Emin Khoja had to move to Guazhou. A fight over who would rule the Dzungar Khanate started in 1745. This caused many rebellions. Two Dzungar nobles, Dawachi and Amursana, fought for control. The Dörbet and Bayad tribes joined the Qing in 1753. Amursana also joined the Qing in 1754. Rulers in Khotan and Aksu also rebelled against Dzungar rule.

In 1755, a Qing army invaded the Dzungar Khanate. They met almost no resistance. Dzungar rule ended in about 100 days. Dawachi tried to escape but was captured and given to the Qing.

After defeating the Dzungar Khanate, the Qing wanted to set up rulers for each of the four Oirat tribes. But Amursana wanted to rule all Oirats. The Qianlong Emperor made him ruler of only the Khoid tribe. Amursana and another Mongol leader, Chingünjav, rebelled against the Qing. Amursana fled to Russia and died there.

When Amursana rebelled, the Aq Taghliq khojas Burhanuddin and Jahan also rebelled. Their rule was not popular. People disliked them for taking what they wanted. In 1758, the Qing sent 10,000 troops against them. The Qing army faced few problems. The khoja brothers fled to Badakhshan. The ruler there captured and executed them. He sent Jahan's head to the Qing. The Tarim Basin was peaceful by 1759.

The Dzungar Genocide

The Qianlong Emperor gave harsh orders against the Dzungars. He said: "Show no mercy at all to these rebels. Only the old and weak should be saved." He believed previous campaigns were too soft. He wanted to make sure no more trouble would occur.

Many Dzungars died between 1755 and 1758. Estimates say 70 to 80 percent of the 600,000 Dzungars were lost. This was due to disease and war. Historians call this "the complete destruction of not only the Dzungar state but of the Dzungars as a people."

According to a Qing scholar, about 40 percent of Dzungar families died from smallpox. 20 percent fled to Russia or Kazakh tribes. 30 percent were killed by Qing soldiers. Khalkha Mongols also took part in the killings. The Dzungar population did not recover for many generations.

Historians describe the destruction of the Dzungars as an "ethnic genocide." The Qianlong Emperor ordered the killing of most Dzungars. The rest were enslaved or sent away. The Encyclopedia of Genocide and Crimes Against Humanity calls this a genocide. The Emperor believed his actions were right. He saw the Dzungars as "barbarians" and "subhuman." He said, "to sweep away barbarians is the way to bring stability to the interior."

His commanders were sometimes slow to follow his orders. He repeated his commands to "exterminate" them. Generals were punished for not being harsh enough. Others were rewarded for their part in the killings. The Emperor ordered Khalkha Mongols to "take the young and strong and massacre them." The elderly, children, and women were spared. But they lost their names and titles. Dzungar women, children, and old men became bondservants to Qing soldiers and loyal Mongols. Their Dzungar identity was erased.

Anti-Dzungar Rebels

The Dzungars had taken over the Uyghurs. They had been invited by the Afaqi Khoja to invade. The Dzungars then made the Uyghurs pay very high taxes.

Uyghur rebels from Turfan and Hami joined the Qing. They asked for Qing help to overthrow Dzungar rule. Uyghur leaders like Emin Khoja were given titles by the Qing. These Uyghurs helped the Qing army fight the Dzungars. The Qing used Emin Khoja to talk to Muslims from the Tarim Basin. They told them the Qing only wanted to kill Oirats (Dzungars). They promised to leave the Muslims alone. The Qing reminded Muslims how much they disliked their Dzungar rulers. This encouraged them to fight the Dzungars alongside the Qing.

Changes in Population

The Qing's actions against the Dzungars emptied northern Xinjiang. The Qing then encouraged many people to settle there. These included Han Chinese, Hui, Central Asian oasis people (Uyghurs), and Manchu soldiers.

Today, the population mix in Xinjiang is similar to the early Qing period. In northern Xinjiang, the Qing brought in Han, Hui, Uyghur, Xibe, and Kazakh settlers. This happened after the Dzungar Oirat Mongols were removed. As a result, Xinjiang during the Qing period was mostly Uyghurs (62%) in the south. Han and Hui people (30%) lived in the north. Other groups made up 8%.

The Qing created Xinjiang as a single, defined area. In Dzungaria, the Qing built new cities like Ürümqi and Yining. After the Qing defeated Jahangir Khoja in the 1820s, 12,000 Uyghur Taranchi families were moved. They went from the Tarim Basin to Dzungaria to settle and repopulate the area.

The Qing settled Manchu, Sibo (Xibe), Daurs, Solons, Han Chinese, Hui Muslims, and Taranchis in the north. Han Chinese and Hui migrants were the largest group of settlers. The Dzungarian basin, once home to Dzungars, is now mostly inhabited by Kazakhs.

Some historians believe the Qing victory helped Islam become more important in the region. The Qing allowed or even supported Muslim culture. The Qing named Dzungaria "Xinjiang" after taking it over. From 1760 to 1820, a lot of grassland was turned into farmland. This was done by new Han Chinese farmers.

Some people think Qing settlements were meant to replace Uyghurs. But Professor James A. Millward says this is not true. The Qing actually stopped Han Chinese from settling in the Uyghur areas of the Tarim Basin. Instead, they sent Han settlers to Dzungaria and the new city of Ürümqi. The state farms settled with 155,000 Han Chinese from 1760 to 1830 were all in Dzungaria and Ürümqi. Very few Uyghurs lived in these areas.

Xinjiang's History Under Qing Rule

Early Qing Rule (1759–1862)

The Qing government called its state Zhongguo ("中國", meaning "China"). In Manchu, it was called "Dulimbai Gurun." The Qianlong Emperor celebrated the Qing conquest of the Dzungars. He said it added new land in Xinjiang to "China." He defined China as a country with many different ethnic groups. He rejected the idea that China only meant Han areas. So, for the Qing, both Han and non-Han peoples were part of "China." This included Xinjiang, which the Qing took from the Dzungars. After conquering Dzungaria in 1759, the Qing announced that this new land was now part of "China."

The Qianlong Emperor disagreed with Han officials who said Xinjiang was not part of China. He believed China was multi-ethnic. He allowed Han people to move to Xinjiang. He also gave Chinese names to cities. He set up civil service exams and Chinese-style government systems. Many Manchu officials supported Han migration to strengthen Qing control. There was a plan to promote Confucianism among Muslims in Xinjiang. This was to be done through state-funded schools. The Qianlong Emperor gave Confucian names to towns and cities in Xinjiang. For example, Ürümqi was named "Dihua" in 1760. He also set up Chinese-style prefectures and counties.

The Qianlong Emperor compared his achievements to those of the Han and Tang dynasties. These earlier dynasties had also ventured into Central Asia. Qing scholars writing about Xinjiang often mentioned Han and Tang era names. The Qing general who conquered Xinjiang, Zhao Hui, is ranked with famous generals from the Tang and Han dynasties. The Qing adopted ways of ruling Xinjiang from both the Han and Tang models. The Qing saw their conquest as continuing the achievements of these older dynasties. They said they were restoring the Han and Tang era borders. Many Manchu and Mongol writers wrote about Xinjiang in Chinese. They used a Chinese cultural viewpoint. Old Chinese stories and place names about Xinjiang were brought back.

Settlement Policies

After the Qing defeated the Dzungar Oirat Mongols, they settled many people in Dzungaria. These included Han, Hui, Manchus, Xibe, and Taranchis (Uyghurs). Han Chinese who had committed crimes or were political exiles were sent to Dzungaria. Chinese Hui Muslims and Salar Muslims from certain religious groups were also exiled there.

The Qing had different rules for different parts of Xinjiang. Han and Hui migrants were encouraged to settle in Dzungaria (northern Xinjiang). But they were not allowed in the Tarim Basin (southern Xinjiang), except for merchants. In areas with more Han Chinese, the Qing used a Chinese-style government.

The Qing government ordered thousands of Han Chinese farmers to settle in Xinjiang after 1760. These farmers came from Gansu. They were given animals, seeds, and tools. This was to make China's rule in the region permanent.

Taranchi was the name for Turki (Uyghur) farmers. The Qing dynasty moved them from the Tarim Basin to Dzungaria. This happened after the Dzungars were defeated. Manchus, Xibo (Xibe), Solons, Han, and other groups were also settled there. Kulja (Ghulja) was a key area for these settlements. Han soldiers and Uyghurs grew grain to supply the Manchu garrisons. The Qing moved about 10,000 Uyghur families from the Tarim Basin to the Ili region. They also moved about 12,000 more Uyghur families from Kashgar after the Jahangir Khoja invasion in the 1820s.

After a revolt by the Xibe in Qiqihar in 1764, the Qianlong Emperor ordered 18,000 Xibe to move to the Ili valley in Xinjiang. In Ili, the Xinjiang Xibe built Buddhist temples and grew crops. One punishment for soldiers was to be exiled to Xinjiang.

In 1765, a large amount of land in Xinjiang was turned into military farms. Chinese settlement grew to keep up with China's population.

The Qing offered money to Han people who moved to Xinjiang in 1776. There were very few Uyghurs in Urumqi during the Qing dynasty. Urumqi was mostly Han and Hui. Han and Hui settlers were mainly in northern Xinjiang (Dzungaria). Around 155,000 Han and Hui lived in Xinjiang around 1803. Most were in Dzungaria. About 320,000 Uyghurs lived mostly in southern Xinjiang (the Tarim Basin). Han and Hui were allowed in Dzungaria but not the Tarim. Han people made up about one-third of Xinjiang's population in 1800. The Qing usually did not allow Han migrants in border regions. But they made an exception for northern Xinjiang. This led to 200,000 Han and Hui settlers in northern Xinjiang by the late 1700s. There were also military farms settled by Han people.

Professor James A. Millward says that Urumqi was founded as a Chinese city by Han and Hui people. He notes that Uyghurs are newer to the city.

Some people wrongly claim that Qing settlements were meant to replace Uyghurs. Professor James A. Millward points out that the Qing stopped Han settlement in the Uyghur Tarim Basin. Instead, they sent Han settlers to Dzungaria and Urumqi. The farms settled with 155,000 Han Chinese from 1760 to 1830 were all in Dzungaria and Urumqi. These areas had very few Uyghurs.

Han and Hui merchants could only trade in the Tarim Basin at first. Han and Hui settlement there was banned. This changed after the Muhammad Yusuf Khoja invasion in 1830. The Qing rewarded merchants for fighting the Khoja by allowing them to settle. By 1870, many Chinese lived in Dzungaria. In the Tarim Basin, there were only a few Chinese merchants and soldiers among the Muslim population.

The Qing gave land to Chinese Hui Muslims and Han Chinese who settled in Dzungaria. Turkic Muslim Taranchis were also moved to Dzungaria in the Ili region. The population of the Tarim Basin doubled during 60 years of Qing rule. No permanent settlement was allowed in the Tarim Basin until the 1830s. After Jahangir's invasion, the Tarim Basin was opened to Han Chinese and Hui settlement. The rebellions in the 19th century caused the Han population to drop.

Population Numbers

Around 1.2 million people lived in Kashgaria by the late 1800s, according to one estimate. Another estimate put the number at 1.015 million.

At the start of the 1800s, about 155,000 Han and Hui Chinese lived in northern Xinjiang. There were more than twice that number of Uyghurs in southern Xinjiang. A census in the early 1800s showed 30% Han and 60% Turkic people. By 1953, it shifted to 6% Han and 75% Uyghur. However, by 2000, the numbers were similar to the Qing era, with 40.57% Han and 45.21% Uyghur. Professor Stanley W. Toops noted that today's population mix is like the early Qing period. Before 1831, only a few hundred Chinese merchants lived in southern Xinjiang. Only a few Uyghurs lived in northern Xinjiang.

The Return of the Kalmyk Oirats

The Oirat Mongol Kalmyk Khanate was founded in the 1600s. Its main religion was Tibetan Buddhism. The Oirats had moved from Dzungaria to the area around the Volga River. In the 1700s, the Russian Empire took them over. The Russian Orthodox church tried to make many Kalmyks become Orthodox Christians.

In the winter of 1770–1771, about 300,000 Kalmyks decided to return to China. They wanted to take back Dzungaria from the Qing dynasty. On their journey, many were attacked and killed by Kazakhs and Kyrgyz. These were their historical rivals. Many more died from hunger and sickness. After months of hard travel, only one-third of the group reached Dzungaria. They had no choice but to surrender to the Qing.

These Kalmyks became known as Oirat Torghut Mongols. After settling in Qing land, the Qing forced the Torghuts to stop being nomads. They had to become farmers. This was a plan by the Qing to make them weaker. They were not good farmers and became very poor. Some even sold their children into slavery. Child slaves were in demand in Central Asia.

Attacks by Kokandi Forces

| Dungan revolt | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Yaqub Bek, Amir of Kashgaria |

||||||||

|

||||||||

| Belligerents | ||||||||

|

|

Kashgaria (Kokandi Uzbek Andijanis under Yaqub Beg) Supported by: |

Hui Muslim rebels | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | ||||||||

| Yaqub Beg Hsu Hsuehkung |

T'o Ming (Tuo Ming, aka Daud Khalifa) | |||||||

| Strength | ||||||||

| Qing troops | Turkic Muslim rebels, Andijani Uzbek troops and Afghan volunteers, Han Chinese and Hui forcibly drafted into Yaqub's army, and separate Han Chinese militia | Hui Muslim rebels | ||||||

The Afaqi Khojas, who were descendants of Khoja Burhanuddin, lived in the Kokand Khanate. They tried to invade Kashgar and take back Altishahr from the Qing dynasty. This happened during the Afaqi Khoja revolts.

In 1827, the southern part of Xinjiang was retaken by Jihangir Khojah. He was a descendant of a former ruler. Chang-lung, a Chinese general, got Kashgar and other rebel cities back in 1828. A revolt in 1829, led by Mohammed AH Khan and Yusuf, was more successful. It led to special trade rights for the "six cities" (Alty Shahr).

Hui merchants helped the Qing fight in Kashgar in 1826 against Turkic Muslim rebels. These rebels were led by Khoja Jahangir. The Muslim (Afaqi) Khojas and Kokands were fought by both the Qing army and Hui Muslim (Tungan) merchants. These merchants had no problem fighting people of their own religion. In 1826, a Hui merchant leader, Zhang Mingtang, died fighting Jahangir Khoja's forces.

In 1826, Jahangir Khoja's forces took six Hui Muslims as captives. They sold them in Central Asia. These people escaped and returned to China through Russia.

When the Khojas attacked in 1830 and 1826, Hui Muslim (Tungan) merchant militias fought them off. Hui Muslims were also part of the Qing Green Standard Army.

Followers of the Ishaqi (Black Mountain) Khoja helped the Qing. They opposed Jahangir Khoja's Afaqi (White Mountain) Khoja group. The Black Mountain Khoja followers supported the Qing against the White Mountain Khoja invasions. This alliance helped defeat Jahangir Khoja's White Mountain rule.

Chinese rule in Xinjiang was supported by the Black Mountain Turkic Muslims. They were called "Khitai-parast" (China worshippers). They were based in Artush. The White Mountain Khojas were against China. They were called "sayyid parast" (sayyid worshippers) and were based in Kucha. These two groups were strongly opposed to each other and did not intermarry.

Ishaqi followers opposed Jahangir Khoja's forces. They helped Qing loyalists. They opposed the "debauchery" and "pillage" caused by Afaqi rule. They allied with Qing loyalists to fight Jahangir. The Qing were helped by the "Black Hat Muslims" (the Ishaqiyya) against the Afaqiyya.

The Kokandis spread false rumors that local Turkic Muslims were plotting with them. This reached the Chinese merchants in Kashgar.

Yarkand was surrounded by the Kokandis. The Chinese merchants and Qing military stayed inside their forts. They used guns and cannons to defeat the Kokandi troops. Local Turkic Muslims of Yarkand helped the Qing capture or drive off the remaining Kokandis.

After the conflict, China and Kokand signed a treaty. The Aksakal became Kokand's representative in Kashgar.

Jahangir Khoja, from the White Mountain group, attacked the Qing in 1825. He killed Chinese civilians and soldiers in Kashgar. He also killed the pro-Chinese Muslim governor of Kashgar. He took Kashgar in 1826. In Ili, the Chinese gathered a large army of 80,000 northern and eastern nomads and Hui Muslims. Jahangir brought his 50,000-strong army to fight them. The Chinese army defeated Jahangir's army. Jahangir hid but was given to the Chinese by the Kyrgyz. He was executed. Yusuf, Jahangir's brother, invaded in 1830 and surrounded Kashgar. The Uyghur Muslim rebel, Jahangir Khoja, was executed by the Qing in 1828 for leading a rebellion. The Kokandis retreated. Turkic people were killed in the city.

The Chinese used 3,000 people who had committed crimes to help stop the "Revolt of the Seven Khojas" in 1846. Local Turkic Muslims refused to help the khojas. This was because the Khojas had taken their daughters and wives. Wali Khan, known for his cruelty, led a rebellion in 1857. He attacked Kashgar, and Chinese people were killed. Wali Khan was known for his harshness. A 12,000-strong Chinese army defeated Wali Khan's 20,000-strong army in 77 days. Wali Khan's allies abandoned him because of his cruelty. The Chinese punished Wali Khan's forces severely. His son and father-in-law were executed.

Until 1846, the region was peaceful under the rule of Zahir-ud-din, a Uyghur governor. But in that year, a new Khojah revolt started under Kath Tora. He took control of the city and ruled harshly. His rule was short. After 75 days, he fled back to Khokand when the Chinese approached. The last Khojah revolt (1857) was also short. It was led by Wali-Khan.

The big Tungani revolt started in 1862 in Gansu. It quickly spread to Dzungaria and the towns in the Tarim basin. Dungan troops in Yarkand rebelled. On August 10, 1863, they killed about 7,000 Chinese. The people of Kashgar also rebelled. They asked for help from Sadik Beg, a Kyrgyz chief. He was joined by Buzurg Khan and Yakub Beg. These two were sent by the ruler of Khokand to help the Muslims in Kashgar.

Sadik Beg soon regretted asking for a Khojah. He marched against Kashgar, which was now under Buzurg Khan and Yakub Beg. But he was defeated. Buzurg Khan became lazy and focused on pleasure. Yakub Beg, however, was energetic and persistent. He took control of Yangi Shahr, Yangi-Hissar, Yarkand, and other towns. He then declared himself the Amir of Kashgaria.

Yakub Beg ruled during the time of The Great Game. This was when the British, Russians, and Qing empires were all trying to gain influence in Central Asia. Kashgaria stretched from Kashgar in southwestern Xinjiang to Ürümqi, Turfan, and Hami in central and eastern Xinjiang. This covered most of what was then called East Turkestan. Some areas around Lake Balkhash in northwestern Xinjiang had already been given to the Russians in the 1864 Treaty of Tarbagatai.

Kashgar and the other cities of the Tarim basin stayed under Yakub Beg's rule until December 1877. That's when the Qing took back most of Xinjiang. Yaqub Beg and his Turkic Uyghur Muslims also declared a holy war against Chinese Muslims in Xinjiang. Yaqub Beg even used Han Chinese to fight against Chinese Muslim forces. Turkic Muslims also killed Chinese Muslims in Ili.

Qing Takes Back Xinjiang

Yakub Beg's rule ended when Qing General Zuo Zongtang reconquered the region in 1877. He did this with the help of Hui Muslims. These included the Khuffiya Sufi leader and Dungan (Hui) General Ma Anliang. Other leaders like Hua Dacai and Cui Wei also helped. Ma Anliang and his Dungan troops fought with Zuo Zongtang against the Muslim rebels. General Dong Fuxiang's army took the Kashgaria and Khotan areas. His army had both Han and Dungan people. Finally, Qing China got back the Gulja region through talks. This was done with the Treaty of Saint Petersburg in 1881.

Zuo Zongtang was the main commander of all Qing troops. His main helpers were the Han Chinese General Liu Jintang and Manchu Jin Shun. Liu Jintang's army had modern German artillery. Jin Shun's forces did not have this. Liu's advance was also faster. After Liu attacked Ku-mu-ti, 6,000 Muslim rebels died. Bai Yanhu had to flee. Qing forces then entered Ürümqi without a fight. Liu's forces destroyed Dabancheng in April. Yaqub's helpers either joined the Qing or fled. His forces began to fall apart. The oasis cities easily fell to the Qing troops. Toksun fell to Liu's army on April 26.

The rebel army's area of control got smaller and smaller. Yaqub Beg lost over 20,000 men. They either left or were killed. At Turfan, Yakub Beg was caught between two armies. In October, Jin Shun continued his advance and met no strong resistance. Zuo Zongtang's Northern Army moved secretly. General Zuo appeared at Aksu, a key city for Kashgaria. Its commander left his post right away. The Qing army then moved to Uqturpan, which also surrendered easily. In early December, all Qing troops began their final attack on Kashgaria's capital. On December 17, the Qing army made a strong attack. The rebel troops were defeated. The remaining troops fled to Yarkant, then to Russian land. With Kashgaria's fall, the Qing had fully reconquered Xinjiang. No more rebellions happened. The Qing authorities began to rebuild and reorganize.

Xinjiang Becomes a Province (1884–1911)

In 1884, Qing China renamed the conquered region. They made Xinjiang ("new frontier") a province. This meant it would be governed like other parts of China proper. The name "Xinjiang" officially replaced older names. These included "Western Regions", "Chinese Turkestan", and "East Turkestan".

The two separate regions, Dzungaria (north) and the Tarim Basin (south), were combined. They became one province called Xinjiang in 1884. Before this, these two parts of Xinjiang had never been one administrative unit.

Many Han Chinese and Chinese Hui Muslims had settled in northern Xinjiang (Dzungaria). But many died in the Dungan Revolt (1862–1877). Because of this, new Uyghur settlers from southern Xinjiang moved into the empty lands. They spread across all of Xinjiang.

After Xinjiang became a province, the Chinese government helped Uyghurs move. They went from southern Xinjiang to other areas. These included areas between Qitai and the capital, and places like Urumqi and Yili. It was during Qing times that Uyghurs settled throughout all of Xinjiang. They moved from their original homes in the western Tarim Basin. The Qing's policies led Uyghurs to believe that all of Xinjiang province was their homeland. The Dzungars were defeated by the Qing. Uyghurs from the Tarim Basin were moved to the Ili valley. The two separate regions were united under one name (Xinjiang). The war from 1864 to 1878 killed many Han Chinese and Hui Muslims. This led to Uyghurs settling in areas where few had lived before. The Uyghur population grew quickly. The original Han Chinese and Hui Muslim population dropped significantly.

Han Chinese officials who came to rule Xinjiang after it became a province encouraged a local form of nationalism. Later, East Turkestani nationalists used this idea. They focused their nationalism on Xinjiang as a clear geographic area.

British and Russian officials spied on each other in Kashgar. This was during The Great Game.

In August 1902, a strong earthquake hit Kashgar and Artux. About 10,000 people died. 30,000 homes were destroyed. The Qing government reduced taxes and helped the victims.

Qing rule of Xinjiang ended with the 1911 Revolution in Xinjiang. This revolution took place in Ili. It led to the fall of the Qing dynasty.

Governors of Xinjiang

- Liu Jintang (Liu Chin-t'ang) 刘锦棠 1884–1889

- Wei Guangtao Wei Kuang-tao 魏光燾

- Wen Shilin 溫世霖 wēn shì lín

- Yuan Dahua 袁大化 (followed by Yang Zengxin after the Qing dynasty ended)

See also

- Qing dynasty in Inner Asia

- Manchuria under Qing rule

- Mongolia under Qing rule

- Tibet under Qing rule

- Taiwan under Qing rule

- History of Xinjiang

- Chinese Turkestan

- Western Regions

- Protectorate of the Western Regions

- Protectorate General to Pacify the West

|