Alvin York facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Alvin York

|

|

|---|---|

York in uniform, 1919, wearing the Medal of Honor and French Croix de Guerre with Palm

|

|

| Birth name | Alvin Cullum York |

| Nickname(s) | "Sergeant York" |

| Born | December 13, 1887 Fentress County, Tennessee, U.S. |

| Died | September 2, 1964 (aged 76) Nashville, Tennessee, U.S. |

| Buried |

Wolf River Cemetery, Pall Mall, Tennessee

(36°32′50.2″N 84°57′14.8″W / 36.547278°N 84.954111°W) |

| Allegiance | United States |

| Service/ |

|

| Years of service |

|

| Rank | |

| Service number | 1910421 |

| Unit |

|

| Commands held | 7th Regiment, Tennessee State Guard (1941–1947) |

| Battles/wars |

|

| Awards |

|

| Spouse(s) |

Gracie Loretta Williams

(m. 1919) |

| Children | 10 |

| Other work | Superintendent of the Cumberland Mountain State Park |

Alvin Cullum York (born December 13, 1887 – died September 2, 1964), also known as Sergeant York, was an American soldier. He became one of the most famous and decorated soldiers of World War I. He received the Medal of Honor for bravely leading an attack on a German machine gun position. During this action, he captured 132 enemy soldiers, took 35 machine guns, and killed at least 25 enemy soldiers.

York's incredible feat happened during the Meuse–Argonne offensive in France. This major battle was part of an effort to break through German defenses and end the war. For his bravery, York received awards from several Allied countries, including France, Italy, and Montenegro.

Alvin York grew up in a rural area of Tennessee. His family farmed, and his father also worked as a blacksmith. Alvin and his ten siblings had little schooling because they had to help their family by hunting, fishing, and working. After his father died, Alvin helped care for his younger brothers and sisters. He also worked as a blacksmith. York was a regular churchgoer, but he was also known for getting into fights. In 1914, he had a religious experience and decided to change his life, becoming even more dedicated to his church.

When World War I started, York was drafted into the army. He first tried to avoid fighting because his religion seemed to forbid violence. However, after talking with his commanders, he became convinced that his faith did not prevent him from serving. York joined the 82nd Airborne Division as an infantry private and went to France in 1918.

Contents

Alvin York's Early Life

Alvin Cullum York was born in a small log cabin in Fentress County, Tennessee. He was the third of eleven children born to William and Mary York. His family was poor, and his father worked as a blacksmith to earn extra money. The family grew their own food, and his mother made all their clothes.

Alvin and his brothers only went to school for about nine months. They had to leave school to help their father work on the farm, hunt, and fish to feed the family. When his father died in 1911, Alvin, as the oldest child still living at home, helped his mother raise his younger siblings. He also worked in railroad construction and as a logger to support his family. Alvin was known as a skilled worker and an excellent shot with a gun.

World War I Service

Even though he had a history of fighting, York regularly attended church and often led the singing. In 1915, he had a powerful religious experience that changed his life. His church, the Church of Christ in Christian Union, did not support violence. York felt worried about fighting in the war. He wrote in his diary, "I was worried clean through. I didn't want to go and kill. I believed in my Bible."

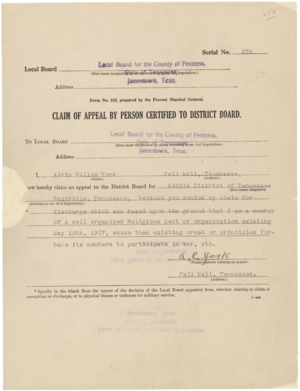

On June 5, 1917, when he was 29, Alvin York registered for the draft, as all men his age had to do. When asked if he wanted to be excused from the draft, he wrote, "Yes. Don't Want To Fight." His first request to be a conscientious objector (someone who refuses to fight for religious or moral reasons) was denied. However, even conscientious objectors could still be drafted for non-combat roles. In November 1917, York was drafted and began his army service.

York kept a diary during his time in the army. He wrote that he refused to sign papers from his pastor or mother asking for him to be excused from the army. Despite his initial request, he later said he was not a conscientious objector.

Joining the Fight

York served in Company G, 328th Infantry, 82nd Division. He was deeply troubled by the conflict between his peaceful beliefs and his military training. He talked for a long time with his commanders, Captain Edward Danforth and Major G. Edward Buxton, who were also religious. They used Bible verses to help York understand that his religion might not be against military service.

York was given a 10-day leave to go home. He returned to the army convinced that God wanted him to fight and would keep him safe. He then served with his division in the St. Mihiel Offensive.

The Medal of Honor Action

On October 8, 1918, during the Meuse–Argonne offensive, York's group was ordered to capture German positions near Hill 223 in France. This is where he earned his Medal of Honor. York later remembered: "The Germans got us, and they got us right smart. They just stopped us dead in our tracks. Their machine guns were up there on the heights overlooking us and well hidden... Our boys just went down like the long grass before the mowing machine at home."

York, along with four other non-commissioned officers and thirteen privates, was sent to sneak behind German lines and silence their machine guns. The group surprised a German unit headquarters and captured many German soldiers. Suddenly, German machine gun fire hit the area, killing six Americans and wounding three. York and the remaining Americans attacked the machine gun position.

York recalled: "And those machine guns were spitting fire and cutting down the undergrowth all around me something awful... As soon as the machine guns opened fire on me, I began to exchange shots with them... All the time I kept yelling at them to come down. I didn't want to kill any more than I had to. But it was they or I."

During the fight, a German officer tried to shoot York but missed. Seeing his soldiers falling, the officer offered to surrender. York accepted. York and his seven men marched back to their unit with over 130 German prisoners. When he reported to his general, Julian Robert Lindsey, the general joked, "Well York, I hear you have captured the whole German army." York replied, "No sir. I got only 132."

York's actions stopped the German machine guns, allowing his unit to continue their attack.

After the Battle

York was quickly promoted to sergeant and received the Distinguished Service Cross. Later, after an investigation, his award was upgraded to the Medal of Honor. General John J. Pershing, the commander of the American forces, presented him with the medal. France also honored him with the Croix de Guerre, the Medaille Militaire, and the Legion of Honour.

Italy gave York the Croce al Merito di Guerra, and Montenegro awarded him its War Medal. He eventually received almost 50 awards.

York's Medal of Honor citation says: "After his platoon suffered heavy casualties and 3 other noncommissioned officers had become casualties, Cpl. York assumed command. Fearlessly leading seven men, he charged with great daring a machine gun nest which was pouring deadly and incessant fire upon his platoon. In this heroic feat the machine gun nest was taken, together with 4 officers and 128 men and several guns."

When asked to explain his actions, York told General Lindsey, "A higher power than man guided and watched over me and told me what to do." Lindsey replied, "York, you are right."

Coming Home and Fame

Before leaving France, York helped create the American Legion, a group for veterans. York's bravery was not widely known in the United States until a magazine article was published in April 1919. The article, titled "The Second Elder Gives Battle," described York's fight and made him a national hero overnight.

People loved York's story because he said God had been with him during the fight. This fit with the popular idea that America's involvement in the war was a holy mission. When he returned to the United States in May 1919, he received a huge welcome. He visited New York City and Washington, D.C., where he met important leaders.

After being discharged from the army, York returned to Tennessee for more celebrations. A week later, on June 7, 1919, York married Gracie Loretta Williams.

York turned down many offers to make money from his fame, including thousands of dollars for appearances and movie rights. Instead, he used his name to support good causes. He pushed for the Tennessee government to build a road in his home region, which was completed in the mid-1920s and named the Alvin C. York Highway.

A group bought a 400-acre farm for York, which was the only gift he accepted. However, the farm was not fully equipped, and York had to borrow money. He later struggled financially, saying, "I could get used to most any kind of hardship, but I'm not fitted for the hardship of owing money." Eventually, public donations helped him pay off his debts.

After the War Years

In the 1920s, York started the Alvin C. York Foundation to improve education in his part of Tennessee. He wanted to build a school for vocational training called the York Agricultural Institute. York focused on raising money, but he often disappointed audiences who wanted to hear about the war. He would explain that he saw little of the war and wanted to focus on helping the children of the mountains.

York faced challenges getting financial support from the state and county. He also disagreed with local leaders about the school's location. He eventually gained control of the original school, which opened in December 1929. During the Great Depression, the state did not provide promised funds, and York even mortgaged his farm to pay for student transportation. He continued to donate money even after he was no longer president of the school in 1936.

In 1935, York began working as a project superintendent for the Civilian Conservation Corps. He oversaw the creation of Byrd Lake at Cumberland Mountain State Park, a large construction project. He served as the park's superintendent until 1940.

In the late 1930s and early 1940s, before America entered World War II, York strongly supported the U.S. getting involved in the war against Germany, Italy, and Japan. At the time, most Americans wanted to stay out of the war, so York's views were not popular. However, he became an important public voice for intervention. In a speech in May 1941, York said, "We must fight again! The time is not now ripe, nor will it ever be, to compromise with Hitler, or the things he stands for."

President Franklin D. Roosevelt often quoted York, especially a part of his speech: "By our victory in the last war, we won a lease on liberty, not a deed to it. Now after 23 years, Adolf Hitler tells us that lease is expiring... We are standing at the crossroads of history. The important capitals of the world in a few years will either be Berlin and Moscow, or Washington and London."

During World War II, York tried to re-enlist in the Army. However, at 54 years old, overweight, and with health issues, he was not allowed to be a combat soldier. Instead, he was made a major in the Army Signal Corps. He visited training camps and helped raise money for the war effort, often paying his own travel costs. He also served on his county's draft board. Even though he was a major and later a colonel in the Tennessee State Guard, newspapers still called him "Sergeant York."

His Story on Film

York worked with journalists to tell his life story. In 1922, a biography focused on his Appalachian background. Later, York allowed a veteran named Tom Skeyhill to use his war diary to write an "autobiography." This book presented York as a simple, religious man from the Tennessee mountains.

For many years, York had a secretary who wrote his speeches and letters. So, while the words represented York's ideas, they were often written by professionals.

York had refused many times to allow a movie to be made about his life. Finally, in 1940, when he was trying to raise money for a Bible school, he agreed. In 1941, the movie Sergeant York was released. Directed by Howard Hawks and starring Gary Cooper as York, the film told his life story and his Medal of Honor action. The movie included some made-up parts but was based on York's diary.

The film was very popular and was the highest-grossing movie of 1941. It received 11 Oscar nominations and won two, including Best Actor for Gary Cooper. York's earnings from the film, about $150,000 in the first two years, led to a long battle with the tax authorities. York eventually built part of his planned Bible school, which taught students until the late 1950s.

Personal Life and Death

Alvin and Gracie York had ten children: seven sons and three daughters. Many were named after famous American historical figures.

York had health problems throughout his life, including surgery, pneumonia, and strokes. From 1954, he was confined to bed due to his health, and his eyesight also failed. He was hospitalized several times in his last two years. Alvin York died at a Veterans Hospital in Nashville, Tennessee, on September 2, 1964, at age 76. He was buried at Wolf River Cemetery in his hometown of Pall Mall, Tennessee.

Awards

York received many awards for his bravery. Here are some of the most important ones:

| Medal of Honor | World War I Victory Medal with three bronze campaign stars |

American Campaign Medal |

| World War II Victory Medal | Legion of Honor (France) |

Military Medal (France) |

| 1914–1918 War Cross with Palm (France) |

War Cross (Italy) |

Order of Prince Danilo I (Montenegro) |

Legacy and Memorials

Finding the Battlefield

In 2006, U.S. Army Colonel Douglas V. Mastriano led a team to find the exact location of York's famous battle. They found American rifle rounds and German weapon parts. This research has been debated by other historians.

Another team, led by Dr. Tom Nolan, used old army records and maps to place the site about 600 meters south of Mastriano's location.

Places Named for York

Many places and monuments honor Alvin York:

- The Sgt. Alvin C. York State Historic Park in Pall Mall preserves his farm.

- The Alvin C. York Bridge crosses the Tennessee River.

- The Alvin C. York Veterans Hospital in Murfreesboro is named after him.

- The Alvin C. York Institute, a high school in Jamestown, was founded by York in 1926.

- York Avenue in Manhattan, New York City, was named for him in 1928.

- A statue of York stands on the grounds of the Tennessee State Capitol.

- In 2007, the 82nd Airborne Division's movie theater at Fort Bragg was named York Theater.

York is also the namesake for awards and military items:

- In the 1980s, the U.S. Army named a weapon system "Sergeant York," but the project was canceled.

- In 2000, the United States Postal Service issued a stamp honoring York as one of the "Distinguished Soldiers."

- The horse in President Ronald Reagan's 2004 funeral procession was named Sergeant York.

- An American football trophy between several Tennessee universities is called the Alvin C. York trophy.

- The U.S. Army ROTC's Sergeant York Award is given to outstanding cadets.

- A memorial at East Tennessee State University features a quote from York.

York in Books and Music

- Author Robert Penn Warren used York as inspiration for characters in his novels At Heaven's Gate (1943) and The Cave (1959). These stories explore how battlefield heroes deal with fame in peacetime.

- The Association of the United States Army published a digital graphic novel about York in 2018.

- Laura Cantrell's 2005 song "Old Downtown" talks about York.

- The Swedish power metal band Sabaton's 2019 album The Great War includes a song called "82nd All the Way," which pays tribute to York's Medal of Honor action.

See Also

- List of Medal of Honor recipients for World War I

- List of members of the American Legion

- List of people from Tennessee

- List of people on stamps of the United States

| Leon Lynch |

| Milton P. Webster |

| Ferdinand Smith |