Amana Colonies facts for kids

|

Amana Colonies

|

|

|

|

| Nearest city | Middle Amana, Iowa |

|---|---|

| Built | 1855 |

| NRHP reference No. | 66000336 |

Quick facts for kids Significant dates |

|

| Added to NRHP | October 15, 1966 |

| Designated NHLD | June 23, 1965 |

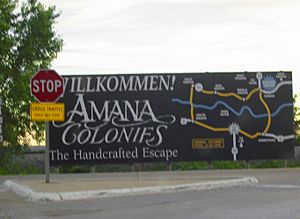

The Amana Colonies are seven special villages in Iowa County, Iowa, United States. They cover about 26,000 acres (105 square kilometers). The villages are: Amana (also called Main Amana), East Amana, High Amana, Middle Amana, South Amana, West Amana, and Homestead.

These villages were built by German people called Radical Pietists. They were treated unfairly in Germany because of their religious beliefs. They called themselves the Community of True Inspiration. They first settled in New York in 1843. But they wanted a more peaceful place, so they moved to Iowa in 1856. They lived a communal life, sharing everything, until 1932.

For 80 years, the Amana Colony was almost completely self-sufficient. This means they made most of what they needed. They were skilled farmers and craftspeople. They passed their skills down through generations. They used hand tools, horses, wind, and water power. They made their own furniture, clothes, and other goods. During the Great Depression, they voted to become a for-profit business. This new group was called the Amana Society.

Today, the Seven Villages of Amana are a popular place for visitors. People come for their restaurants and craft shops. The colony was named a National Historic Landmark in 1965.

Here are the populations of the seven villages from the 2010 Census:

- Middle Amana (581 people)

- Amana (Main Amana) (442 people)

- South Amana (159 people)

- Homestead (148 people)

- West Amana (135 people)

- High Amana (115 people)

- East Amana (56 people)

The Community of True Inspiration (Amana Church) still holds church services. They meet in the Middle Amana meeting house. Larger services and Sunday school happen in the Main Amana meeting house.

Contents

Amana's Early History

Religious Beginnings in Europe

The Amana Colony started from a religious group in Germany in 1714. It was led by Eberhard L. Gruber and Johann F. Rock. They were unhappy with the Lutheran Church. They began to follow the teachings of Pietists. Gruber and Rock shared their beliefs widely. Their group was first known as the New Spiritual Economy.

They believed that God spoke through certain people. These people had a "gift of inspiration." They were called "instruments" (Werkzeug). This meant they were tools used by God to speak directly to his people.

To share their faith, Rock and Gruber traveled through Germany, Switzerland, and the Dutch Republic. Their group became known as the Community of True Inspiration. Followers were called Inspirationalists. They faced problems with German governments. This was because they refused to be soldiers. They also would not send their children to Lutheran public schools. Some followers were put in prison or lost their belongings. Many Inspirationalists moved to Hesse, a more open German state. There, their numbers grew a lot.

After Gruber and Rock died, the group's numbers went down. But in 1817, three new instruments appeared. They were Michael Krausert, Barbara Heinemann, and Christian Metz. Krausert soon left, but Metz and Heinemann helped the Community grow again.

Heinemann stepped back in 1823, leaving Metz as the main leader. The Community still faced problems for their beliefs. In the 1830s, Metz thought of leasing large areas of land. This would be a safe place for the Community. They first leased land from a cloister (a religious community) near Ronneburg. Then they leased from the Arnsburg Abbey. They also expanded to Engelthal Abbey in 1834. They managed all their land together. This is where the idea of communal life started to grow among them. By the late 1830s, the Community was doing very well.

Moving to America

The government in Hesse started charging the Community more money. This happened because of money problems in the late 1830s. Metz and other leaders knew they needed a new home. On August 27, 1842, they decided to move to the United States.

The Community arrived in New York on October 26, 1842. For three months, leaders looked for land for a new shared community. They decided to buy 5,000 acres (20 square kilometers) of the Buffalo Creek Reservation. This land was near Buffalo. It had recently become open for new settlers. Their first settlement was called Ebenezer.

More than 800 members moved from Germany to Ebenezer. In 1843, they created a "provisional constitution." This document explained their goals. They called themselves the Ebenezer Society. All land and buildings were shared. Wealthy settlers were expected to help pay for community costs. At first, they planned to divide the land later. But leaders saw that this would cause problems. So, in 1850, they changed the constitution. The Community became fully communal, meaning everything was shared forever.

The 5,000 acres were enough for the first 800 villagers. But the community's success brought more settlers. By 1854, they needed more land. Also, the city of Buffalo was growing fast nearby. Church elders worried this could be a bad influence. Buffalo's growth also made land prices too high to expand Ebenezer. Metz and other leaders met in August 1854. They decided to send four men to look for a new home out west. They looked in the new Kansas Territory but couldn't agree on a spot.

Then, two elders went to Iowa to look at large government land grants. They found good land near the Iowa River. They went back to Ebenezer and suggested buying it. The Inspirationalists sent four men to buy the land and all nearby properties. The first village in what would become the Amana Colonies was started in 1855.

Founding the Amana Colonies

The new colony was first going to be named Bleibetreu. This is German for "remain faithful." But people found it hard to say in English. So, they chose Amana. This is a Biblical name with a similar meaning.

Under Iowa law, the Community had to become a business. So, the Amana Society was created in 1859 to govern them. Soon after, they agreed on a new constitution. This document had twelve articles. It was very similar to their earlier Ebenezer Constitution.

One early problem was that settlers had no train access. The closest station was 20 miles (32 km) away in Iowa City. But in 1861, the Mississippi and Missouri Railroad built a station in nearby Homestead. The Community saw how important this train link was. They bought the entire village of Homestead (Heimstätte).

This made their land holdings grow to 26,000 acres (105 square kilometers). This included 10,000 acres (40 sq km) of timberland, 7,000 acres (28 sq km) of cultivated fields, and 4,000 acres (16 sq km) for grazing. Most of the land is in Iowa County.

By 1862, five more villages were laid out. This brought the total number to seven:

- Amana vor der Höhe (High Amana)

- Süd-Amana (South Amana)

- West-Amana (West Amana)

- Ost-Amana (East Amana)

- Mittel-Amana (Middle Amana)

Each village had between 40 and 100 houses. They also had a church, school, bakery, dairy, wine-cellar, post office, sawmill, and general store. Every able-bodied man was expected to serve in the fire department. Most houses were two stories high. They were built with local sandstone, which has a unique color. They are mostly square with sloped roofs.

The last of the 1,200 Inspirationalist settlers from New York arrived in 1864. By 1908, the Community had grown to 1,800 people. They owned assets worth over $1.8 million.

Life Before 1932

Marriage and Family Life

At first, marriage was only allowed "with the consent of God." This consent came through the Werkzeug (instrument). Marriage was seen as a sign of spiritual weakness. Wedding ceremonies were not joyful parties. Instead, they were serious events to show the importance of the task. Having children was also not encouraged at first.

Over time, views on marriage became more relaxed. The Great Council was later given the power to approve marriages. Men could not marry until they were 24 years old. If the Great Council approved, the couple would wait a year before marrying. An elder would bless the marriage. The community would provide a wedding feast. The community did not allow divorce. Second marriages, even for a widow, were strongly disapproved of. If someone married a person from outside the colonies, they would be sent away for one year. This was true even if the outsider wanted to join the society.

Dining Together

People in Amana did not cook in their own homes. Instead, they ate together in groups of 30 to 45 people. Communal kitchens, each with its own garden, hosted the meals. Men sat at one table, while women and small children sat at another. Prayers were said in German before and after meals. Meals were not meant for socializing, so talking was not encouraged.

There were as many as 55 communal kitchens. Sixteen were in Amana, ten in Middle Amana, and nine in Homestead. South and West Amana had six each. East and High Amana had four each. The kitchen boss (Küchebaas) was in charge of kitchen tasks. This included cooking, serving, preserving food, and raising chickens. Kitchen staff were chosen by the Bruderrat (Brotherhood Council).

Communal kitchens were usually large, two-story buildings. They had a home for the Küchebaas attached. Kitchens typically had a big brick stove, a wood or coal oven, and a 6-foot (1.8 m) long sink. At first, kitchens had to get water from the nearest well. But they were the first buildings to get connected to the colony's water system. Kitchens were named after their Küchebaas.

Around 1900, the communal kitchen idea slowly changed. Married residents started eating in their own homes. Food was still cooked in the communal kitchens. But housewives would take the food home. Kitchen staff and single residents still ate in the communal kitchens.

Each kitchen worked on its own. But menus were mostly the same across all colonies. This was to make sure everyone got a fair share. Saturday night meals might include pork sausages, boiled potatoes, cottage cheese with chives, bread with cream cheese, and streusel (a crumbly topping). Sunday noon meals had rice soup, fried potatoes, creamed spinach, boiled beef, streusel, and tea or coffee. Menus changed with the seasons. For example, more beef and pork were served in autumn and winter. This was because it was easier to keep fresh meat then.

Work Life

Women often worked in the kitchens, communal gardens, and laundries. There were about eight different jobs for women. Men had 39 different jobs. These included barber, butcher, tailor, machine shop worker, and doctor. Children also helped with jobs. Boys did harvesting and farm work. Girls helped in the kitchens.

Children stayed with their mothers until they were two years old. Then, they went to Kinderschule (children's school) until age seven. After that, children went to school six days a week, all year. They stayed until they were 14 or 15. At school, they shelled corn, cleaned seeds, picked fruit, and studied reading, writing, and math.

Amana was known for being welcoming to outsiders. They would never turn away someone in need. They fed and sheltered homeless people who passed through on the train. Some outsiders were even hired as workers. They received good pay, a temporary home, and three meals a day in the communal kitchen. Amana also hired many outside workers for industrial and farm jobs. These workers helped in the woolen shop, the calico-printing shop, and other places.

Worship and Church Life

The church was another important part of the society. It was run by the Board of Trustees. Children and their parents went to church together. Mothers with young children sat in the back. Other children sat in the first few rows. Men and women sat separately during worship. Men sat on one side, and women on the other. This practice continues today. Older people and "in-betweens" (people in their thirties and forties) went to a separate service. Where members sat showed their status in the community. Services were held eleven times a week. They did not use musical instruments or sing hymns.

Amana and the Outside World

Amana interacted with the outside world by buying and selling goods. Each village had a central store where all goods were bought. By the 1890s, these stores were buying many goods and raw materials from outside. Middle Amana alone had over 732 invoices from outside companies. Amana bought anything needed to run the society well. This included raw wool, oil, grease, starch, pipes, and fittings. Most of the grain for their flour mill was bought from outside. The printing business used cotton goods from the southern states. This shows that Amana was not completely separate from the wider economy.

The Great Change

In March 1931, during the Great Depression, the Great Council told the Amana Society that they were in serious financial trouble. The Depression hit the Colony hard. A fire had also badly damaged the woolen mill and destroyed the flour mill less than ten years earlier. At the same time, Society members wanted more personal freedom.

The Society agreed to split into two groups. The non-profit Amana Church Society would handle the community's spiritual needs. The for-profit Amana Society was set up as a joint-stock company. This change was finished in 1932. It became known in the community as the Great Change.

Amana Since the Great Change

Most people living in the Amana Colony speak three languages. They speak American English, High German (Hochdeutsch), and a special dialect called Amana German (Kolonie-Deutsch). This dialect comes from High German. But it has many influences from American English. For example, the word for rhubarb is Piestengel. This combines the English word "pie" with the German word for stalk or stem.

The Amana Society, Inc., still owns and manages about 26,000 acres (105 square kilometers) of farm, pasture, and forest land. Farming is still an important part of the economy today. This is just like it was in communal times. Because the land was not divided when communalism ended, the Amana landscape still shows its shared past. Also, over 450 buildings from the communal era still stand in the seven villages. These are clear reminders of the past.

On June 23, 1965, the National Park Service recognized the Amana Colonies as a National Historic Landmark. When the National Register of Historic Places was created a year later, the Colonies were automatically added.

Amana Farms has Iowa’s largest privately owned forest. Amana Farms built a 1,600,000 US gallon (6,100 cubic meter) anaerobic digester. This project got money from the Iowa Office of Energy Independence. The digester makes fertilizer, heat for buildings, and methane for making electricity. It processes waste from companies like Genencor International and Cargill. It also processes manure. This helps reduce local methane emissions.

Amana Refrigeration Company

The most famous business that came from the Amana Society is Amana Refrigeration, Inc. George C. Foerstner worked in the woolen mill. After the Great Change, he became a traveling salesman for the mill. When Prohibition ended in 1933, Foerstner saw a need for beverage coolers. He started the Electric Equipment Company in 1934 with $3,500 of his own money.

The company was sold to the Amana Society in 1936. It was renamed the Electrical Department of the Amana Society. Foerstner stayed on as manager. The company won the Army-Navy "E" Award twice during World War II. This was for making military products. Goods were made in the Middle Amana woolen mill.

In 1947, the company made the first commercial upright freezer. Two years later, the Amana Society sold the Electrical Department. An investment group organized by Foerstner bought it. The company was renamed Amana Refrigeration, Inc. It grew to make refrigerators and air conditioners.

The Raytheon Corporation bought Amana Refrigeration on January 1, 1965. But the Amana division mostly ran itself. Amana made the first useful commercial microwave oven in 1967. The division was sold to Goodman Global in 1997. Then it was sold to Maytag in 2001. It became part of the Whirlpool Corporation when Whirlpool bought Maytag in 2006. In October 2020, Whirlpool sold the Amana, Iowa refrigerator plant property for $92.6 million. Amana will keep making Amana, JennAir, KitchenAid, Maytag, and Whirlpool refrigerators at the plant. This will happen under a long-term lease agreement.

Tourism in Amana

Today, heritage tourism is very important to the Amana area's economy. There are hotels and bed and breakfasts for visitors. There are also many independent shops, local artists, craftspeople, and restaurants. These restaurants serve family-style meals.

Local non-profit groups and the Amana Society, Inc., work to preserve the area. They use historic preservation rules to protect Amana's natural and built environment.

Education in Amana

The Clear Creek–Amana Community School District runs public schools for the community. Amana Elementary School is in Middle Amana. Clear Creek–Amana Middle School and Clear Creek–Amana High School are in Tiffin.

Amana High School in Middle Amana was built after a vote in 1935. The school closed in 1991. Clear Creek–Amana Middle School used to be in Middle Amana.

Notable people

- Barbara Heinemann Landmann – a spiritual leader

- Christian Metz – a spiritual leader

- William Henry Prestele – a lithographer (someone who makes prints)

- Joanna E. Schanz – a basket maker

- Bill Zuber – a professional baseball player

See also

In Spanish: Amana (Iowa) para niños

In Spanish: Amana (Iowa) para niños